Stonewall: The birth of gay power

THE SIXTIES is often perceived as an era of social upheaval and orgiastic revelry. But for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) folks in America, the efflorescence of sexual expression did not begin until the waning months of that decade in the heart of the nation’s then-largest bohemian enclave and gay ghetto, New York’s Greenwich Village. The Stonewall Riots that began in the wee hours of June 28, 1969,1 lasted six nights and catapulted the issue of sexual liberation out of the Dark Ages and into a new era.

The relative freedoms and social acceptance that millions of particularly urban American LGBT people experience today would have seemed as surreal to that earlier generation as the prospect of electing an African-American president. On the heels of the U.S. military’s postwar purge of gays, President Eisenhower signed a 1953 executive order that established “sexual perversion” as grounds for being fired from government jobs. And since employment records were shared with private industry, exposure or suspicion of homosexuality could render a person unemployable and destitute. “Loitering in a public toilet” was an offense that could blacklist a man from work and social networks, as lists of arrestees were often printed in newspapers and other public records. Most states had laws barring homosexuals from receiving professional licenses, which could also be revoked upon discovery. Sex between consenting adults of the same sex, even in a private home, could be punishable for up to life in prison, confinement in a mental institution, or even castration.

In 1917, foreign LGBT people were barred from legally immigrating to the United States due to their supposed “psychopathic personality disorder.”2 Illinois was the only state in the country, since 1961, where homosexuality was not explicitly outlawed. New York’s penal code called for the arrest of anyone in public wearing fewer than three items of clothing “appropriate” to their gender. And California’s Atascadero State Hospital was compared with a Nazi concentration camp and known as a “Dachau for queers” for performing electroshock and other draconian “therapies” on gays and lesbians. One legal expert argues that in the 1960s, “The homosexual…was smothered by law.”3

This repression existed alongside a growing acknowledgement of the existence of lesbians and gays in literature, theater, movies, and newspapers. Cultural outlets exposed an expanding gay world to people who may never have known of its existence, including those who would finally discover affirmation and a name for their desires. In an interview with NPR’s Terry Gross, Daughters of Bilitis (DOB) co-founder Phyllis Lyon recounts how when she met her lover and the group’s co-founder Del Martin in 1949 she had no idea there was such a possibility as lesbianism.4 By the 1960s, that would no longer be possible for an adult woman in urban America. Bestsellers like James Baldwin’s Another Country and Mary McCarthy’s The Group included lesbian characters in their plots. And the New York Times ran a front-page story on the city’s gay male scene as “the most sensitive open secret,” leading to a spate of feature articles—ranging from hostile to sympathetic—in Life, Look, Newsweek, and Time.5

The groups that formed to organize gays and lesbians in the 1950s remained small, largely disconnected, and conflicted in their political agendas well into the 1960s. Seven years after its New York City launch, the Mattachine Society’s local chapter had fewer than one hundred members in 1963, while New York’s DOB chapter had twenty-two voting members in 1965.6 The continued insistence on referring to their movement as “homophile,” to avoid any explicitly sexual connotations, betrayed their groups’ conservatism. Most telling was the internalized homophobia that dominated the homophile movement’s leadership, which looked to medical professionals who deemed their sexuality “deviant” and requiring a “cure.” DOB’s publication, the Ladder, was still urging its members “to stop the breeding of defiance toward society” and to exhibit “outward conformity.”7 Donald Webster Cory, a pseudonym for a leading Mattachine activist, took on a handful of younger militants advocating public protests and a rejection of the medical pathologizing of gays for “alienating [the movement] from scientific thinking…by its constant, defensive, neurotic, disturbed denial” that homosexuals were sick.8 It was a milestone, therefore, when militants like Frank Kameny won over the Washington, D.C.’s Mattachine chapter in 1975 to approve a resolution proclaiming that “homosexuality is not a sickness…but is merely a preference, an orientation, or propensity, on par with, and not different in kind from, heterosexuality.”9 Another signpost on the road ahead appeared when students at New York’s Columbia University founded the first university-chartered gay organization, the Student Homophile League in 1967, declaring equality between all sexual orientations.10

Imagine the Black civil rights movement of that era having to challenge white supremacist ideas within its ranks and one begins to grasp the enormous ideological obstacles that permeated the thinking of many LGBT people.

But the involvement of many mostly closeted gays and lesbians in the civil rights, women’s, and anti-Vietnam War movements shaped a new generation of budding radicals chafing at their own oppression. Influenced by the Black Power militants who had made slogans like “Black is beautiful” and “Black power” the argot of the radical movements, by 1968 the homophile movement adopted “gay is good” and “gay power” as their rallying cries. A glimpse of things to come was perceptible at the formation of the East Coast Homophile Organizations (ECHO) in 1963, where militants adopted plans to picket openly against legislation barring gays from federal employment. Wearing suits and ties, dresses and heels, handfuls of picketers began an annual tradition of protesting outside Philadelphia’s Independence Hall on July 4, 1965, to remind the nation that there remained a group of Americans who had yet to receive humane treatment and rights.

In San Francisco’s Tenderloin district there had even been a Stonewall dress rehearsal of sorts in the summer of 1966 when a cop’s manhandling of a transvestite at a local eatery frequented by drag queens and gay street youth led to “general havoc” including smashed windows and the burning of a newsstand.11 But nothing as dramatic or far-reaching as what occurred in New York in 1969 took off from that fierce expression of rage.

Out of the bars and into the streets!

In a society filled with hatred, fear, and ignorance of homosexuality there was at least one public venue for socializing where gays and lesbians in most major towns and cities could go—the bars. But as with all public life for LGBT people, the bars also provided a site for police and authorities to harass and humiliate their victims. From police entrapment in public cruising spots and raids on bars for perceived “disorderly” conduct within, the cultural openings and nascent activism of gays and lesbians was frustrated by state repression from California to New York. Despite there being no explicit laws against serving gays, many bars refused to do so, and there was no legal recourse since kissing or dancing with a member of the same sex and cross-dressing were considered disorderly. It was in this context that the Mafia came to run many of the drinking establishments that catered to gays, lesbians, and transgendered people in New York City. The Stonewall Inn was no exception.

Located at the crossroads of Christopher Street and Seventh Avenue South, near a major subway station, and steps away from the former offices of the nation’s largest independent weekly, the Village Voice, the Stonewall Inn was dark with two bars, a jukebox, and an eclectic crowd of drag queens, gay street youth, cruising men, and a smattering of lesbians. There was no running water to wash the glasses of watered-down booze and beer that were rinsed in a murky tub behind the main bar, leading to at least one known outbreak of hepatitis among customers.12 Black, Latino, and white LGBT folks mixed and mingled there, one of the few joints around with dancing. Filmmaker Vito Russo described the place as “a bar for the people who were too young, too poor or just too much to get in anywhere else. The Stonewall was a street queen hangout in the heart of the ghetto.”13

As with most drinking establishments that catered to gays, the Mob owner, Fat Tony, paid off the cops to keep the place from being shut down for city code violations. For a bar that took in between $5,000 and $6,000 on an average Friday night, Fat Tony had little problem skimming off $1,200 a month to assuage New York’s Finest in the local Sixth Precinct.14 Yet raids were still commonplace at bars like the Stonewall—one had occurred there just days before the riots—but a choreographed kabuki routine was established between mobsters and cops who each played out their roles to keep up appearances, while never threatening their mutual access to easy cash at the expense of the LGBT clientele. Bars generally reopened the night after a raid, as happened at the Stonewall the last week of June 1969. Rumors and speculation to this day swirl around the reasoning for the raid’s response on the night of June 28. Police asserted that gay Wall Street brokers were being blackmailed there, exposure that would have destroyed the lives of those men, who would not be legally bonded by brokerage houses if their homosexuality were known. Others suggest that it was the shocking death of forty-seven-year-old gay icon Judy Garland earlier that week that exacerbated anger that night.

Whatever the immediate catalyst for the unprecedented response to a routine raid, the fact is that lives immersed in shame and secrecy in a world rocked by social upheaval and defiance could not have remained untouched by the ferment that surrounded them much longer. It was, after all, 1969.

Under the pretext that Stonewall was operating without a liquor license, a handful of police led by Deputy Inspector Seymour Pine, figured they’d make quick work of shutting it down and rounding up its patrons that night. Sexist and homophobic stereotypes of gays and lesbians certainly reassured the cops that resistance was unlikely at best, irrelevant at worst. Initially, when the cops forced the men and women inside to line up, show drivers’ licenses, and prepare to be arrested, everyone did as they were told, despite some cheeky backtalk. But as crowds gathered outside and the harassment built, a once buoyant, even carnivalesque mood was transformed into active rage. The New York Daily News coverage of the riots speaks volumes about the unadulterated scorn LGBT people were accustomed to in those years. Headlined “Homo Nest Raided, Queen Bees Are Stinging Mad,” the article went on to explain,

She sat there with her legs crossed, the lashes of her mascara-coated eyes beating like the wings of a hummingbird. She was angry. She was so upset she hadn’t bothered to shave. A day old stubble was beginning to push through the pancake makeup. She was a he. A queen of Christopher Street.

Last weekend the queens had turned commandos and stood bra strap to bra strap against an invasion of the helmeted Tactical Patrol Force. The elite police squad had shut down one of their private gay clubs, the Stonewall Inn at 57 Christopher St., in the heart of a three-block homosexual community in Greenwich Village. Queen Power reared its bleached blonde head in revolt. New York City experienced its first homosexual riot. “We may have lost the battle, sweets, but the war is far from over,” lisped an unofficial lady-in-waiting from the court of the Queens.15

The Village Voice coverage of events of the first night of rioting not only captures the spirit of the fight, but also the contempt of even supposed progressive writers through the language they employed to describe that evening. Keep in mind, this account was written by two journalists two decades before anyone ever thought to openly invoke words like “fag” and “dyke” as ironically empowering—in 1969, these were insensitive, nasty slurs.

[A]s the patrons trapped inside were released one by one, a crowd started to gather on the street…initially a festive gathering, composed mostly of Stonewall boys who were waiting around for friends still inside or to see what was going to happen. Cheers would go up as favorites would emerge from the door, strike a pose, and swish by the detective with a “Hello there, fella.” The stars were in their element. Wrists were limp, hair was primped, and reactions to the applause were classic….

Suddenly the paddywagon arrived and the mood of the crowd changed. Three of the more blatant queens—in full drag—were loaded inside, along with the bartender and doorman, to a chorus of catcalls and boos from the crowd. A cry went up to push the paddywagon over, but it drove away before anything could happen. With its exit, the action waned momentarily. The next person to come out was a dyke, and she put up a struggle—from car to door to car again….

Pine ordered the three cars and paddywagon to leave with the prisoners before the crowd became more of a mob. “Hurry back,” he added, realizing he and his force of eight detectives, two of them women, would be easily overwhelmed if the temper broke….

It was at that moment that the scene became explosive. Limp wrists were forgotten….

…“Pigs!” “Faggot cops!” Pennies and dimes flew. I stood against the door. The detectives held at most a 10-foot clearing. Escalate to nickels and quarters. A bottle. Another bottle. Pine says, “Let’s get inside. Lock ourselves inside, it’s safer.”…

The door crashes open, beer cans and bottles hurtle in. Pine and his troop rush to shut it. At that point, the only uniformed cop among them gets hit with something under his eye. He hollers, and his hand comes away scarlet. It looks a lot more serious than it really is. They are suddenly furious. Three run out in front to see if they can scare the mob from the door. A hail of coins. A beer can glances off Deputy Inspector Smyth’s head.

…The cop who is cut is incensed, yells something like, “So, you’re the one who hit me!” And while the other cops help, he slaps the prisoner five or six times very hard and finishes with a punch to the mouth. They handcuff the guy as he almost passes out….

…The exit left no cops on the street, and almost by signal the crowd erupted into cobblestone and bottle heaving. The reaction was solid: they were pissed. The trashcan I was standing on was nearly yanked out from under me as a kid tried to grab it for use in the window-smashing melee. From nowhere came an uprooted parking meter—used as a battering ram on the Stonewall door….

By now the mind’s eye has forgotten the character of the mob; the sound filtering in doesn’t suggest dancing faggots any more. It sounds like a powerful rage bent on vendetta….

…One detective arms himself in addition with a sawed-off baseball bat he has found. I hear, “We’ll shoot the first motherfucker that comes through that door.”…

I can only see the arm at the window. It squirts liquid into the room, and a flaring match follows. Pine is not more than 10 feet away. He aims his gun at the figures.

He doesn’t fire. The sound of sirens coincides with the whoosh of flames where the lighter fluid was thrown….It was that close….16

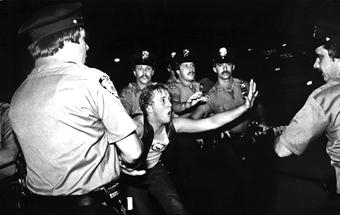

After this initial confrontation lasting forty-five minutes, the riot squad arrived, and for hours a cat and mouse game ensued between groups of police and groups of rioters, numbering around two thousand in all. In a decade punctuated by riots in most major cities, it was a rare victory for the rioters over the police. The fact that it had been “faggots,” “trannies,” “dykes,” and street kids who delivered a decisive blow to the police was lost on nobody. News of the first night’s rebellion spread widely, and by the following evening organized leftists, and more gays, lesbians, transvestites, and transgendered people came out to see what would happen, catch a glimpse of the previous night’s detritus, and snag their own opportunity for revenge against police who had humiliated and beaten them all for years. The violence resumed each evening through Wednesday night, July 2, with taunts from young gays and chants by experienced activists stoking police violence through the labyrinthian streets of the West Village. Mortified that they had been disgraced by a bunch of “queers,” the cops returned in force each night to try and recapture Christopher Street. They never did.

Most eyewitness reports recount the leading role played by some of the most despised and oppressed groupings within the gay community. A multiracial lot of poor gay teens, many living on the streets because they had been tossed out of homes or ran away from abuse, taunted the cops with abandon. Transvestites who camped and mocked the cops while striking blows with spiked heels showed that defiance and humor could be complementary. And some reports credited at least one butch lesbian with having shamed the macho men into shedding their passivity and fighting back that first night with her furious display of resistance. Deputy Inspector Pine, who had fought in the Second World War and was injured in the Battle of the Bulge where 19,000 American soldiers died, said of the first night of rioting, “There was never any time that I felt more scared than I felt that night.”17 Gay Beat poet Allen Ginsburg walked through the Village that weekend and poignantly summed up the atmosphere: “You know, the guys there were so beautiful—they’ve lost that wounded look that fags all had 10 years ago.”18

From a riot to a movement

What separates the Stonewall Riots from all previous gay activism was not merely the unexpected nights-long defiance in the streets, but the conscious mobilization of new and seasoned activists in the riot’s wake who gave expression to this more militant mood. Like a dam bursting, Stonewall was the eruption after twenty years of trickling progress by small handfuls of men and women whose conscious organizing gave way to the spontaneous wave of fury. The riots alone would not be remembered today for transforming gay politics and life had they not been followed by organizations that transmitted the raw outrage into an ongoing social force.

A clash between the old guard organizers and newly rising militants was apparent from the Sunday of the riots, when Mattachine activists who’d met with the mayor’s office and police posted this sign on the front of the Stonewall: “We homosexuals plead with our people to please help maintain peaceful and quiet conduct on the streets of the Village—Mattachine.”19 Their pleas were ignored. Each night thereafter through Wednesday, more and more gays and straight leftists, from socialists and Black Panthers to the Yippies20 and Puerto Rican Young Lords, arrived on the scene to participate in the latest confrontation with police.

By the time the riots subsided, activists began distributing leaflets that read: “Do You Think Homosexuals Are Revolting? You Bet Your Sweet Ass We Are,”21 and announced a meeting at a Village leftist venue known as Alternative U. What began as an ad hoc committee of Mattachine-New York to organize a march in commemoration of the riots evolved into a full-blown organization, the Gay Liberation Front (GLF). In conscious tribute to the South Vietnamese National Liberation Front then fighting the U.S. government in Southeast Asia, these activists wanted to confront not just the stifling homophobia of U.S. society, but the entire oppressive and exploitative imperial edifice. From the earliest gathering, disputes about the political perspective of the movement were framed in terms of whether to focus exclusively on LGBT issues and consciousness-raising or to embrace a broader revolutionary agenda and solidarity with other oppressed minorities.

But most all of the newly radicalizing activists agreed that the old guard’s approach needed to be upended. Looking back years later on the debates between the DOB and Mattachine leaderships and new radicals, one prominent militant, Jim Fouratt, summarized the tensions of that time: “We wanted to end the homophile movement. We wanted them to join us in making the gay revolution. We were a nightmare to them. They were committed to being nice, acceptable status quo Americans, and we were not; we had no interest at all in being acceptable.”22

One agenda key to all the new gay liberationists was the act of coming out, since most gays remained publicly closeted. As gay historian John D’Emilio notes, this cathartic act of coming out publicly—to one’s family and friends, at work and on the streets—“quintessentially expressed the fusion of the personal and political that the radicalism of the late 1960s exalted.”23 Shedding their internalized homophobia may have opened gays and lesbians to occasional attacks, but it also allowed them to claim a sense of self-respect that was incompatible with life in the closet. “Coming out,” D’Emilio explains, “provided gay liberation with an army of permanent enlistees.”24 In a strange sense, the right wing’s fears that gay visibility would encourage others to either experiment with homosexuality or at least be tolerant of it turned out to be accurate. While the right may shudder at that fact, the widening visibility and confidence of a gay movement did pave the way for others to come out and has transformed public consciousness ever since. Gallup polls taken over thirty years on questions regarding homosexuality show enormous advances. Since 1977, public support for legalization of “homosexual relations between consenting adults” has risen from 43 percent to a record-breaking 59 percent in 2007. In that same poll, 89 percent of Americans today believe that “homosexuals should have equal rights in terms of job opportunities.”25 Stonewall’s wake created the conditions for this rise in social consciousness.

The influence of small radical groups in the GLF was evident in its statement to one underground newspaper, the Rat:

We are a revolutionary homosexual group of men and women formed with the realization that complete sexual liberation for all people cannot come about unless existing social institutions are abolished. We reject society’s attempt to impose sexual roles and definitions of our nature. We are stepping outside these roles and simplistic myths. We are going to be who we are. At the same time, we are creating new social forms and relations, that is, relations based upon brotherhood, cooperation, human love, and uninhibited sexuality. Babylon has forced us to commit ourselves to one thing…revolution.26

In response to the Rat’s question, “What makes you revolutionaries?”, they wrote,

We identify ourselves with all the oppressed: the Vietnamese struggle, the third world, the blacks, the workers…all those oppressed by this rotten, dirty, vile, fucked-up capitalist conspiracy.27

One of the earliest protests launched by GLF was against the Village Voice, the very newspaper whose account of the Stonewall Riots was circulated and cited in periodicals throughout the world. To raise money through dances and to publicize its activities, GLF tried to advertise in the Voice, which refused to print the word “gay.” Considering the word to be offensive and “equitable with ‘fuck’ and other four-letter words,”28 the Voice’s offices were soon deluged with petitions carrying thousands of signatures demanding they alter their policy, forcing them to concede. As dozens of chapters of GLF spread across the country, even to Britain, similar protests converged on newspapers demanding respect and representation. The Los Angeles Times had even refused to print the word “homosexual” in its advertising, despite less flattering references to gays in cultural reviews in the “family newspaper.”29 The San Francisco Examiner was picketed that fall for referring to gays and lesbians as “semi-males” and “women who aren’t exactly women.”30 Even the right to put up fliers and distribute gay newspapers in the bars catering to LGBT people had to be fought for and won through protest. GLF launched its own newspaper, Come Out! in the fall of 1969, which became a popular means of disseminating ideas and movement information. Gay Power and Gay also premiered that year, each selling 25,000 copies per issue, expressing the hunger for an independent LGBT press.31

Later that year, a group of activists split from the GLF and formed a new single-issue group, the Gay Activist Alliance (GAA), with a constitution that defined its agenda as “exclusively devoted to the liberation of homosexuals and avoids involvement in any program of action not obviously relevant to homosexuals.”32 Right from the get-go they aimed their sights on getting rid of discrimination against LGBT people in the workplace and putting heat on local politicians to change bigoted laws. GLF and GAA collaborated on many efforts, including protests against further police raids and the annual Stonewall commemoration march.

Perhaps one of the greatest movement victories of that era came out of protests against the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) designation of homosexuality as a mental illness. So long as LGBT people were pathologized as sick, social and legal constraints would remain. Angry protests disrupted the usually placid APA gatherings in the early 1970s. Militants Barbara Gittings and Frank Kameny demanded and took a seat at the table to discuss the damage psychiatrists’ “therapies” were doing to the lives of gays and lesbians. One gay psychiatrist appeared on an APA panel wearing a mask and disguising his voice to plead for an alteration of that body’s policy. In 1973, the APA’s Board of Trustees removed homosexuality from its list of mental illnesses.33 Five years later, gay and lesbian psychiatrists formed a caucus within the APA—never again would a gay shrink have to hide from his colleagues behind a grotesque mask.

It was a major breakthrough when on August 21, 1970, Black Panther co-founder Huey Newton wrote the first openly pro-gay statement by a major heterosexual movement activist of any race, which was printed in the pages of The Black Panther, the party’s newspaper. In “A Letter From Huey to the Revolutionary Brothers and Sisters About the Women’s Liberation and Gay Liberation Movements,” Newton admitted that the Black Panther Party had been inconsiderate concerning gays and lesbians. He argued, “Homosexuals are not given freedom and liberty by anyone in the society. Maybe they might be the most oppressed people in the society.” Newton also accepted the criticism of gay activists, “The terms ‘faggot’ and ‘punk’ should be deleted from our vocabulary, and especially we should not attach names normally designed for homosexuals to men who are enemies of the people.”34 This set the stage for the Revolutionary Peoples’ Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia the following month, in which 13,000 radicals participated.35 The radical transformation taking place in the minds of many gay activists was reflected in the following excerpt from Gay Flames pamphlet, written by the Chicago chapter of GLF.

[B]ecause of the rampant oppression we see—of black, third world people, women, workers—in addition to our own; because of the corrupt values, because of the injustices, we no longer want to “make it” in Amerika….

Our particular struggle is for sexual self-determination, the abolition of sex-role stereotypes and the human right to the use of one’s body without interference from the legal and social institutions of the state. Many of us have understood that our struggle cannot succeed without a fundamental change in society which will put the source of power (means of production) in the hands of the people who at present have nothing….

But as our struggle grows it will be made clear by the changing objective conditions that our liberation is inextricably bound to the liberation of all oppressed people.36

- Sometimes the date Friday, June 27, 1969 is given, though the actual raid took place after midnight.

- John D’Emilio, William B. Turner, and Urvashi Vaid, eds., Creating Change: Sexuality, Public Policy, and Civil Rights (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000), 11.

- David Carter, Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution(New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2004), 14–15.

- Fresh Air interview with Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon by Terry Gross, first aired December 29, 1992. Del Martin died on August 27, 2008, two months after she and Phyllis Lyon married in San Francisco after fifty-five years together as lovers.

- D’Emilio, Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities: The Making of a Homosexual Minority in the United States 1940–1970 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983), 138.

- Ibid., 173.

- Quoted in Ibid., 186.

- Quoted in Ibid., 167.

- Quoted in Ibid., 164.

- Donn Teal, Gay Militants: How Gay Liberation Began in America, 1969–1971 (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1971), 37.

- Carter, Stonewall, 109.

- Ibid., 80.

- Quoted in Ibid., 74.

- Ibid., 77, 79.

- “Homo Nest Raided, Queen Bees Are Stinging Mad,” New York Daily News, July 6, 1969.

- Quoted in Teal, Gay Militants, 2–3.

- Quoted in Carter, Stonewall, 160.

- Quoted in Teal, Gay Militants, 7.

- Quoted in Carter, Stonewall, 196.

- The Youth International Party (Yippies) was a hippie movement established in the late 1960s that adhered to anti-authoritarian methods and used guerrilla theater as a means of advancing its countercultural platform.

- Quoted in Teal, Gay Militants, 19.

- Quoted in Martin Duberman, Stonewall (New York: Plume, 1994), 229.

- D’Emilio, Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities, 235.

- Ibid., 236.

- Lydia Saad, “Tolerance for Gay Rights at High-Water Mark,” May 29, 2007, www.gallup.com/poll/27694/Tolerance-Gay-Rights-HighWater-Mark.aspx, [September 6, 2008].

- Quoted in Carter, Stonewall, 219.

- Quoted in Ibid., 220.

- Ibid., 226.

- Quoted in Teal, Gay Militants, 57.

- Ibid., 54.

- Carter, Stonewall, 242.

- Quoted in Teal, Gay Militants, 110.

- Eric Marcus, Making History: The Struggle for Gay and Lesbian Equal Rights, 1945–1990 (New York: Harper Collins, 1992), 253.

- Ibid., 151.

- Ibid., 155.

- “Working Paper for the Revolutionary Peoples’ Constitutional Convention,” Chicago Gay Liberation, Gay Flames, pamphlet No. 13, September 1970 [original available at Northwestern Library, Deering Special Collections].

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Google+

Google+ Tumblr

Tumblr Digg

Digg Reddit

Reddit StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon