The Legacy of the IWW

“You men and women should be imbued with the spirit that is now displayed in far-off Russia and far-off Siberia where we thought the spark of manhood and womanhood had been crushed.... Let us take example from them. We see the capitalist class fortifying themselves today behind their Citizens’ Associations and Employers’ Associations in order that they may crush the American labor movement. Let us cast our eyes over to far-off Russia and take heart and courage from those who are fighting the battle there.”

—Lucy Parsons, at the founding convention of the IWW, 19051

To master and to own

THE INDUSTRIAL Workers of the World (IWW) occupies a proud place in the tradition of radicalism and labor struggle in the United States. Capturing the imagination of an entire generation of radicals, organizers, socialists, and anti-capitalists of every stripe, it was in many ways a uniquely North American organization, and at its height counted among its members nearly every notable radical and class fighter of its time. Its members included the great leader of the Socialist Party (SP) Eugene Debs, organizer for the Western Federation of Miners Big Bill Haywood, revolutionary journalist John (Jack) Reed, union organizer Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, the famous “friend of the Miners” Mother Jones, founder of the Socialist Labor Party Daniel DeLeon, leader of the Great Dublin lockout of 1913 and the Easter Uprising James Connolly, founder of the Catholic Worker society Dorothy Day, agitator and wife of Haymarket martyr Lucy Parsons, leader of the packinghouse and steel strikes of 1919 William Z. Foster, and even Helen Keller.

The IWW planted the idea of industrial unionism deeply in the politics of the US labor movement, paving the way for the industrial union drives of the CIO (Congress of Industrial Organizations) in the 1930s. Wobblies2 participated in some of the first sit-down strikes in US history, and built unions across color and gender lines, from the Philadelphia waterfront to the backwaters of the Jim Crow South. Their belief in industrial unionism was seen as a weapon to be used against the capitalist class, embodied in the quotation from Marx contained in the preamble of the IWW’s constitution: “Instead of the conservative motto of a fair days wage for a fair days work, we must inscribe on our banner the revolutionary watchword, ‘abolition of the wages system.’” And in the final battle between contending classes, the general strike would be used to break the power of the capitalists and usher in the “cooperative commonwealth.”3

Though never comparable in size to other union federations, the ideas of the IWW spread far beyond its formal membership, through its easily recognizable propaganda, its art, and through its famous songs written by, among others, Ralph Chaplin, who penned “Solidarity Forever,” and Joe Hill, who wrote some of the most famous labor ballads and hymns ever produced for the world working-class movement. The cultural impact of the IWW on the history of the US Left persists to this day, with many of the songs written by its bards still being sung at protests and demonstrations.

The IWW was an organization that stood for the self-emancipation of the working class, occupying a proud place in the tradition of revolutionary socialism in the US. But there were central questions and problems in the aims and practices of the IWW, which went unresolved throughout its history, and eventually led to its ultimate demise as a fighting organization. Most centrally, the IWW tried to be both a union and a revolutionary organization at the same time, and in attempting this, never fully succeeded at either.

The revolutionary year 1905

The founding convention of the IWW took place against the backdrop of the revolutionary mass strike wave sweeping across Russia, so meticulously documented and analyzed in the Polish-born revoulutionary Rosa Luxemburg’s The Mass Strike. Mutinies had spread throughout the Russian military, and soviets were formed in the cities, throwing the Tsar onto the defensive and forcing the granting of a limited constitutional monarchy, to the celebration of the workers movement across the world. In this electric atmosphere, the convention was a veritable who’s who of the American labor left, with Big Bill Haywood presiding as chair and Debs, Parsons, and Mother Jones all urging unity and class combat. Frequent reference was made to the unfolding revolution in Russia. A delegate from the dockworker’s union of Hoboken, New Jersey put forth a resolution supporting the Russian labor movement and pledging “moral support . . . and financial assistance as much as lies within our power to our persecuted, struggling and suffering comrades in far off Russia,” which passed with no recorded dissenting votes.4

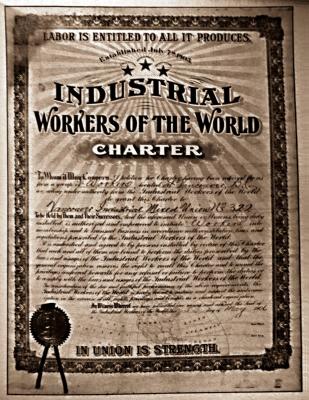

On July 8, 1905, after eleven full days of stormy debate and urgent discussion, the Industrial Workers of the World was formed. With most of the unions mentioned above affiliating as well as those connected to the Socialist Trades and Labor Alliance (ST&LA) and other small local bodies, the membership in the first few months of the IWW totaled around 5,000 members.5 The Western Federation of Miners would affiliate in 1906, bringing another 22,000 members. A small but new union federation had been created, based on the politics of class struggle and the idea that “the working class and the employing class have nothing in common.”6 Indeed, many of the arguments over the course of the convention revolved around what this would mean in practice. What would be the IWW’s relationship with other union federations around the world? How would it relate to other left wing groups and parties? Was the IWW a political organization? If not, how would it respond to national or international events? By the end of the convention, these questions would still be left unanswered, and the dual role the IWW assigned to itself would become manifest through early years of faction fights and continuous blurring of the lines between industrial union and revolutionary organization.

Rejecting the AFL

The founders of the IWW were looking for a new model of unionism, one that rejected the backwardness of the then-dominant American Federation of Labor (AFL). Founded in 1886, the AFL surpassed the declining Knights of Labor to become the one large union federation in the US by the twentieth century boasting nearly two million members by 1904, but it was plagued with problems7.

As industry developed on a massive scale in the US, the AFL continued to organize along craft lines, leading Wobblies to dub it the “American Separation of Labor.” As early as the 1890s, union militants were demanding a fundamental change in the organizing practices and organizational structure of the AFL. As US capitalism continued to develop and concentrate into enormous corporations and monopolies, it only made sense for the labor movement to organize itself accordingly in order to be able to effectively organize the new mass industries. This was radically different than the mechanism by which craft unions operated; namely, as a job trust, restricted to the better- off layers of the working class who could afford the high initiation fees, and then could expect to be paid high wages based on the union’s control over the supply of skilled labor.

Philip Foner, in his monumental history of the US labor movement, wrote:

The adverse effects of the introduction of machinery upon unions of skilled craftsmen brought sharply to the fore the whole question of the proper form of organization. It was clear to many in the labor movement that the changes in the techniques of production could only be met effectively by a change in the union structure. . . . While its inability to cope with the rapidly changing industrial conditions was advanced as the most important objection to craft unionism, it was also criticized for giving employers a great advantage in collective bargaining by enabling them, in the process of negotiating with several crafts separately, to play one union against another, and for causing bitter quarrels among the craft unions in the form of jurisdictional disputes. Changes in techniques of industry and the introduction of new machinery and new materials, it was pointed out, had made inevitable the jurisdictional quarrels among the craft unions. It was impossible under modern industrial conditions to draw an exact line where the work of one craft left off and that of another began.8

Widespread and continuous squabbling over jurisdiction led many AFL unions to turn against each other, instead of fighting together against the bosses. With separately negotiated contracts expiring at different times, employers could count on one craft at a job site or workplace downing tools while all the others continued to work. This gave rise to what would come to be called “union scabbing.” One of the unions participating in the founding of the IWW, the Brewery Workers, dealt with this problem consistently before breaking away from the AFL. In 1901,

the Executive Council [of the AFL] helped to break a strike of the brewery workers in New Orleans because the union attempted to organize the beer drivers. The New Orleans Central Trades and Labor Council, under instructions from the AFL Executive Council, gave Local 701, International Brotherhood of Teamsters, jurisdiction over the drivers, notwithstanding the fact that the contract of the Brewery Workers provided more pay and better conditions than did Local 701’s. When the brewery workers struck, the scabs who took their places and aided the employers to break the strike were organized into a Federal Labor Union by an AFL organizer, acting on instructions from the Executive Council.9

Leaders of AFL unions continuously promoted “labor-management partnership” in the labor press and delighted at hobnobbing with industrialists. Just like today, many leaders of the AFL drew enormous salaries for their times, far above what the working members of their unions brought home. They flaunted their wealthy lifestyles and defended their oftentimes lavish spending as part of the role they were supposed to play as the big shots running their union.

These union leaders were not embarrassed by reports of their wealth. They “justified” their conduct on various grounds. They argued that “union leaders should be in a position to make a good showing when they meet with the employers;” that businessmen had more respect for a union when they saw it could afford to provide its leadership with a “living standard” comparable with that of heads of corporations, and that the social acceptance of union leaders by the capitalists at meetings and dinners helped to break down the widespread opinion in the United States that representatives of organized labor were “undesirable citizens.”10

Anyone who voiced opposition to their proud lifestyles was dubbed a “misfit” or a “troublemaker.”11 One such “labor leader” gave voice to the outlook of this type in 1900: “The union should be run on just the same business principles as a business firm is. The union needs a man to manage it just as much as a business house needs a manager. Then why not reward him as the business firm rewards its manager?”12

Added on to the widespread corruption, stupidity, and backwardness of AFL leaders were the policies of the federation which widely restricted immigrants, women, and people of color from joining unions. Despite passing lofty sounding resolutions at conventions about the universal brotherhood of the working class, the AFL enforced a morass of rules and regulations which served to bar a majority of the US working class from its ranks.

In 1900, the AFL annual convention officially endorsed Jim Crow unionism, allowing for “separate but equal” locals (assuming unions were actually trying to recruit Black workers). An article of the federation’s constitution was rewritten to allow that “separate charters may be issued to central labor unions, local unions or federated labor unions, composed exclusively of colored workers where in the judgement of the Executive Council it appears advisable.”13 Certain affiliated unions had their own constitutions which explicitly barred Blacks from joining, and in others the color bar was unspoken but equally effective.

Other policies worked to ensure that immigrants and women would be kept out, considering their concentration in the least skilled and lowest paid sectors of the economy, oftentimes in the new industries which the AFL refused to attempt to organize. Patronizing sexism served to keep women from joining unions or to ignore them when they did it on their own, and racism and xenophobia towards groups of immigrants (most notoriously against Asian immigrants, which the AFL lobbied to bar from entering the US) played their own roles in ensuring the AFL would only ever represent a tiny minority of the working class.

Certain bureaucratic procedures also worked to hamstring the federation, with high initiation dues being among the biggest barriers, as in 1900 when a group of women shoe workers in Illinois wrote to the AFL concerning their attempt to form their own union: “We are anxious to go into the Boot and Shoe Workers union and wrote to Mr. Eaton [the general secretary-treasurer] to that effect. He sent us a copy of the by-laws and when we found out what the high dues were we voted by a large majority not to go in as the dues were too high, and we simply do not earn enough to pay them.”14

It was no wonder then that nearly every notable American radical wanted nothing to do with the “labor leaders” who created and maintained such an organization. Mired in organizational forms from a bygone era, with a membership restricted to a puny minority of the US working class concentrated in the skilled crafts, and with a leadership politically rotten to the core, the union militants and anti-capitalists of the IWW were eager to build a radical alternative to the swamp that was the AF of L.

Stinking “sewer socialism”

But the IWW was also rejecting something else in its founding. It was rejecting the policies and activity of the Socialist Party as a model for revolutionary change. With the apparatus controlled predominantly by the right wing of the party, which was led and supported by lawyers and professionals like Morris Hillquit in New York and Victor Berger in Wisconsin (an avowed racist who insisted on the complete separation of races and refused to support women’s suffrage), the Socialist Party, like many of the other parties of the Second International, supported socialism on paper but did little to actually fight for it.

One of the most prominent leaders of the SP, Berger was continiously elected to public office in Milwaukee around this time. He boasted of what he called “sewer socialism,” so named because Milwaukee constructed a sewer system for the city, among other public works, under a socialist city commission. Unintentionally creating a perfectly descriptive epithet for his brand of politics, Berger, priding himself on his respectability and his disdain for agitation and conflict, came to represent the right wing of the SP and its lack of revolutionary politics or aims.

With an almost exclusively electoral strategy, the Socialist Party often disdained to become involved in class struggle, seeing it as a distraction from the real task of electing more and more “socialists” to office, so that the US could peacefully and slowly move toward socialism. The likes of Hillquit and Berger elaborated a strategy that the United States could simply evolve into socialism by increasing the voting returns for their candidates. Hillquit was quoted to have said, “So far as we Socialists are concerned, the age of physical revolution. . .has passed.”15 One historian of the SP noted that “Berger argued strongly against those Socialists who were constantly speaking of revolution, which he interpreted to mean a ‘catastrophe,’ as the path to socialism. He recognized and partially accepted Marx’s statement that ‘force is the midwife at the birth of every new epoch,’ but saw in this ‘no cause for rejoicing.’ Looking for ‘another way out,’ Berger found it in the ballot.”16

In terms of the labor movement, the leadership of the SP generally attempted to win favor within the AFL by accommodating to the reactionary bureaucrats who ran the federation, having given up after several failed attempts to elect members to high ranking positions with the AFL. Again lacking any substantive fighting strategy, the Socialist Party viewed its initial goal of “capturing” the AFL through the lens of wheeling and dealing during union elections or winning majorities at conventions to pass resolutions in favor of socialism. Adhering to a policy of “non-interference” within the AFL, the right wing in the leadership of the SP hoped to win the goodwill of Gompers and his lieutenants, in an attempt to emulate the social democratic parties of Europe (and especially the German SPD), where the party performed propaganda for socialism and expected unions to provide the votes for their deputies in Parliament. During a later faction fight against those sympathetic to the IWW within the party, the SP leadership actually brought Karl Legien, the conservative opportunist head of the German union federation, to the US on a tour speaking in favor of expelling all of the pro-syndicalists from the party.

The Socialist Party certainly counted among its members a large number of dedicated revolutionaries, who were actively participating in class struggle in different locales throughout the US. But the left wing largely abstained from making a bid for power within their own party, and when they did eventually enter the fray, the left wing would find itself running up against an entrenched bureaucracy of party officials with the full resources of the party at their command. Because it attracted all kinds of elements into its ranks (from bigots like Berger to real revolutionaries like Eugene Debs or, for a while, Bill Haywood) the SP was politically divided, and during the life of the IWW, was almost entirely controlled by its most conservative elements who had no desire or designs for revolution. In response to the political shortcomings and the reformism of the party leaders, the relationship between the IWW and the Socialist Party was generally one of reciprocal hostility.

Faction fights and early organizing

As it would turn out, the IWW was plagued by faction fights from the very beginning of its existence, despite the confidence and good feeling at the first convention. In the next few conventions, three distinct groups emerged, fighting for the organization to go in three different directions. These three factions would spend the next several years battling for the political leadership of the IWW, spending precious time and resources embroiled over the future of the organization.

The first group, including the Western Federation of Miners and the United Metal Workers, was ultimately happy to adopt a bold and militant manifesto at the founding convention, but was more interested in actually building a strong and permanent industrial union federation to provide support to its own affiliate unions as an alternative federation to the AFL. By the third or fourth convention, these unions had pulled out of the IWW, taking with them their substantial membership and resources.

The second group, headed by Daniel DeLeon and his Socialist Labor Party (which consisted predominantly of German-speaking immigrant workers who held membership in the ST&LA), insisted on the IWW being closely identified with the SLP, as the labor appendage of his party. DeLeon’s conception of the role of the IWW was based on an extremely mechanistic understanding of the relationship between politics and economics, allotting unions the exclusive domain of bargaining over wages but acting as loyal voting members for the SLP, which would only function in the electoral realm. DeLeon was also renowned for his ultra-sectarianism, a practice which didn’t win him or his supporters many friends.

One historian noted,

DeLeon and his SLP disciples gave only lip service to industrial unionism. When they spoke at IWW meetings or circulated literature during strikes, they concentrated on criticizing the Socialist Party. Not unexpectedly, the IWW general executive board warned all IWW representatives in June 1907 against introducing political fights into union affairs. Directing its message specifically toward SLP members, the general executive board warned: “No organizer or representative of the IWW can . . . use his position . . . for any act of hostility . . . against such other organizations, even though individual members of the latter may be opposed to the IWW. 17

When the credentials committee refused DeLeon a seat at the fourth convention in 1908, DeLeon walked out, taking his supporters with him and founded his own IWW, which quickly faded into obscurity. It is at this point that the IWW officially declared itself a “non-political” group, specifically disavowing electoral work or identification with any left-wing political organization. By a close vote, the convention delegates rejected the original clause in the 1905 preamble calling for workers to “come together on the political. . . field.”18 Many IWW members rejected DeLeon’s sectarianism without rejecting political action outright. The majority of IWW members, however, in particular the itinerant workers in the Northwest, whom DeLeon regarded as “bums,”19 were against endorsing any party or participating in politics.

What was left of the IWW at this point represented the group that wanted the organization to be a revolutionary union: that is, both an effective fighting industrial union and at the same time, a revolutionary organization geared towards the overthrow of capitalism and the abolition of the wage system. Since its first convention in 1905, the IWW had picked up thousands of new members through new organizing and new affiliations, but by the end of the faction fights in 1908, membership in what was left of the IWW again numbered some five to six thousand.20

Revolutionary unionism

As part and parcel of being a “revolutionary union,” the IWW rejected the practices of the AFL entirely, and opened its doors to all workers, regardless of ethnicity, race, gender or craft. This was an incredible political advance to make in 1905. However, the IWW’s approach to organizing had some weaknesses. The IWW refused to sign contracts with management after winning strikes, claiming that signed contracts were a betrayal of the principle of class struggle—how could a union sign a truce, it reasoned, with the class enemy? In a speech, Haywood elaborated on the stance of the IWW: “No contracts, no agreements, no compacts. These are unholy alliances, and must be damned as treason when entered into with the capitalist class.”21

In 1912, an IWW union in Montana signed a contract with a local boss, and had their charter revoked immediately by the leadership of the IWW. The general executive board of the IWW told the local members that the leadership “saved the IWW itself from dishonor, disgrace and so forth that would necessarily have occurred had this local remained in the IWW with a contract with the employing class.”22 The political principle of refusing to sign contracts would seriously hamstring the IWW in the years to come, giving them no real ability to build permanent bases of membership and maintain work standards in the new, mass industries which operated in relatively stable, urban communities. At a more basic level, turning the anti-contract principle into a shibboleth was unrealistic, given that workers cannot engage in unremitting direct action. This point of IWW practice wound up gravely hindering their its to be an effective industrial union.

As well, the IWW refused to set up any health or death benefit funds for its members, claiming that these would only lead their members to think that capitalism could be reformed. Decades before the Social Security system began providing a modicum of support to injured or older workers, many thousands of AFL members who might have been sympathetic to the IWW had considerable investment in these programs, and understandably hesitated to leave their AFL unions to forgo the benefits they had paid into for years as union members. The IWW also refused to set up permanent strike funds, a policy which would prove disastrous when long strikes were unavoidable.

Then there was the question of dual unionism. Long had labor in the United States strived to create a single union federation covering all of the local unions in the country. When the IWW was first created, it set as its aim the organizing of the unorganized, but in the first few years of its existence it drew most of its members from preexisting AFL locals, raiding them for members when faced with the inability to win their affiliation.23

As the IWW became a pole of attraction for thousands of militant rank- and-file members of the AFL who left their own unions to join the IWW, it enshrined the power of the right-wing bureaucrats within the AFL. As Foner notes,

one of the main results of the launching of the IWW was that the conservative leaders of the AF of L gained a tighter control over the affairs of the Federation. A number of socialists who had been combatting the Gompers’ leadership most vociferously inside the AF of L dropped away from the Federation into the new industrial union, while those who remained increasingly worked hand-in-glove with the Gompers’ leadership.24

Rather than having a political strategy aimed towards supporting radicals still within the AFL, or building rank-and-file reform movements, the IWW encouraged AFL members to simply quit and join the IWW in order to “destroy the AFL.” This translated into a significant number of years where Gompers faced little to no organized opposition against his backward leadership within the two-million-member federation.

Turning their backs on “politics” was also a source of weakness for the Wobblies. When the IWW declared itself to be a “non-political” group, it meant more than just disavowing electoral politics or refusing to be an appendage to any political group. Being non-political came to mean an avoidance of forms of class struggle beyond the realm of the shop floor. When they rejected the practices of the SLP and the SP, the IWW would throw out the baby with the bathwater.

The IWW, for example, opposed the women’s suffrage movement, protective labor legislation, and even old age pension legislation (Haywood once quipped in an article opposing a pension law, “Give to the worker the full product of his toil and his pension is assured”25). The no-politics clause of the IWW would serve to put it at odds with other working-class forces who were fighting for meaningful reform, eventually leaving them on the sidelines. The IWW’s confusion over whether it was a union or a revolutionary group would be a constant source of disruption running throughout its history.

Who joined the IWW?

The names of Wobbly leaders and the iconography of the IWW indicate a vast diversity in the people who became members of the organization, ranging from European immigrants to native born radicals.

The social composition of the IWW changed depending on which region of the country it was organizing. In the East, at the center of mass industry, the IWW tended to be composed of predominantly foreign-born workers, many from the recently arrived waves of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe.

The IWW made organizing immigrant workers a top priority, using immigrant workers as organizers, like Italian-born Joseph Ettor and Arturo Giovanitti, and emphatically rejecting the AFL’s hesitancy (or in some cases outright hostility) to organizing the “mobocracy,” as Samuel Gompers (himself an immigrant from Holland) was said to have remarked about the newest waves of immigrants from eastern and southeastern Europe. Ethnic community ties also linked together to strengthen the bonds of solidarity so pivotal for maintaining strong local unions. By becoming a regular part of immigrant community life, the IWW earned itself the loyalty of the brutally exploited newly arrived transplants.

Sophie Cohen, a Jewish immigrant teenager in Paterson, New Jersey remembered attending IWW picnics, dances, and mass meetings when she was fifteen. She and her teenage friends went on to attempt to organize the mills where they worked:

I wasn’t an official organizer, but when I became a weaver, a girlfriend and I would take jobs in unorganized factories and try to organize them. We would refuse the four looms, saying it was too much for us. Because we were young girls, we were permitted to work only two. After a few weeks, we would hand out leaflets and call for an organizing meeting. We looked so innocent that the managers never thought we were capable of even believing in a union.26

Out West, the IWW tended to be made up more of native-born workers or immigrants from northern Europe, people like Big Bill Haywood, Vincent St. John, James P. Cannon, and Joe Hill, who was a Swedish immigrant. As Melvin Dubofsky a historian of the IWW noted:

Census statistics disclose that, unlike other American industrial centers of that era, all the major mining districts in Colorado, Idaho, and Montana [all locales with a heavy IWW presence] were dominated by native-born majorities. Moreover, the foreign-born came largely from the British Isles (including Ireland) and Scandinavia, and were hardly representative of the more recent waves of immigration. An unusually large number of foreign-born workers in the West also became naturalized citizens.27

The tough style of the IWW, with its mistrust of the state and its self-reliance on direct action had a particular appeal to the rugged frontier mentality of hard rock miners in the Rockies, the “timber beasts” of the Pacific Northwest, and the agricultural workers who followed the harvests from California to Canada. Fred Thompson, a postwar leader of the IWW, recalled his own experiences mingling with the Western IWW:

Their speech was different—much more seasoned, and even their cussing was original and avoided stereotype. I think they shunned stereotype in all things. Their frontier was a psychological fact—a rather deliberate avoidance of certain conventions, a break with the bondage to the past. Yet there was far more “etiquette” on the job than I had observed back east. . . In the bunkhouse or jungle or job there was this considerate-ness that was rare back east. Individuality and solidarity or sense of community flourished here together, and with a radical social philosophy. . .[they] demanded more respect for themselves and accorded more respect to each other than I found back east.28

Related to this was the IWW practice of organizing and recruiting transient, informal laborers, or hoboes, who performed much of the work of developing the western US. While the rest of the labor movement was generally opposed or unwilling to organize migrant workers, the IWW made it a priority and developed special organizing tactics to pursue their membership in the organization. An 1914 article published in the IWW’s publication Solidarity declared,

The nomadic worker of the West embodies the very spirit of the IWW. His cheerful cynicism, his frank and outspoken contempt for most of the conventions of bourgeois society. . .make him an admirable exemplar of the iconoclastic doctrines of revolutionary unionism. His anamolous position, half industrial slave, half vagabond adventurer leaves him infinitely less servile than his fellow worker in the East. Unlike the factory slave of the Atlantic seaboard and the central states he is most emphatically not “afraid of his job.” No wife and family encumber him. The worker of the East, oppressed by the fear of want for wife and babies, dare not venture much.29

Ironically, it was the immigrant “factory slaves” of the Eastern seaboard cities that the IWW first organized. As time went on, however, because of its inability to build permanent and strong local unions in the major cities where mass industry was located, the focus of much IWW organizing shifted to the West, where it was impossible to build stable membership among the migrant workers and hoboes anyway, and legislative or “political” activity held little appeal because of voting restrictions on migrants.

The IWW was the most advanced organization in the labor movement of its time when it came to the question of fighting the oppression of Blacks and immigrants. In a society gripped by virulent Jim Crow racism in the South, xenophobic anti-Asian bigotry in the West, and anti-European immigrant bashing in the rest of the country, the IWW’s practical and rhetorical stand against race prejudice stands out in sharp relief against the chauvinism of the AFL and the moderate leadership of the Socialist Party. Its basic creed, “An injury to one is an injury to all,” was a heartfelt principal of the organization in all its work. At its founding convention, the IWW voted on by-laws that stated, “No working man or woman shall be excluded from membership because of creed or color.”30

On the West Coast, the IWW made some headway recruiting Asian workers, whom most of the labor movement racistly derided as a “yellow peril.” At the Stuttgart Congress of the Second International in 1907, US delegate Morris Hillquit (despite being ridiculed by revolutionaries from other parties because of his stance on the issue) endorsed the restriction of Asian immigrants. According to Hillquit, the immigration of Asian workers “threatens the native born with dangerous competition and usually provides a pool of unconscious strikebreakers. Chinese and Japanese workers play that role today, as does the yellow race in general.31” The IWW rejected this wholeheartedly, editorializing in their paper:

All workers can be organized regardless of race or color, as soon as their minds are cleared of the patriotic notion that there is any reason of being proud of having been born of a certain shade of skin or in an arbitrarily fenced off portion of the earth.. . . If the American workers need fear any ‘yellow peril’ it is from the yellow socialists.32

A significant number of Black workers joined the IWW, as it was the only working-class organization in the United States at the time that openly and consistently welcomed them. In their organizing in the South and also on the East Coast, the IWW was the only union Blacks could join to fight for better conditions on the job. At no time did the IWW organize segregated unions.

Starting in 1910 the IWW made a concerted appeal to Black workers to join. Its publications, including in the Jim Crow South, were filled with vigorous denunciations of racism. In a December 1912 article entitled “Down with Race Prejudice,” published in the IWW’s Southern newspaper The Voice of the People, Phineas Eastman asked his “fellow workers of the South if they wish real good feeling to exist between the two races (and each is necessary to the other’s success), to please stop calling the colored man ‘Nigger’—the tone some use is an insult, much less the word. Call him Negro if you must refer to his race, but ‘fellow worker’ is the only form of salutation a rebel should use.”33

A 1919 IWW pamphlet, Justice for the Negro: How Can He Get it? began by denouncing the “two lynchings a week” that have been “killing colored men and women for the past thirty years.” It continued:

The wrongs of the Negro are not confined to lynching, however. When allowed to live and work for the community, he is subjected to constant humiliation, injustice and discrimination. In the cities he is forced to live in the meanest districts, where his rent is doubled and tripled, while conditions of health and safety are neglected in favor of the white sections. In many states he is obliged to ride in special “Jim Crow” cars, hardly fit for cattle. Almost everywhere all semblance of political rights is denied him.. . .

Throughout this land of liberty, so-called, the Negro worker is treated as an inferior; he is underpaid in his work and overcharged in his rent; he is kick about, cursed and spat upon; in short, he is treated, not as a human being, but as an animal, a beast of burden for the ruling class. When he tries to improve his condition, he is shoved back into the mire of degradation and poverty and told to “keep his place.”

The article concluded that the only way to fight racism was not through “protests, petitions, and resolutions,” but through strikes. The Black worker “has. . .one weapon that the master class fears—the power to fold his arms and refuse to work for the community until he is guaranteed fair treatment.”34

The heroic IWW-led strikes of Black and white timber workers in Louisiana demonstrated both the possibilities for interracial working class action and the IWW’s commitment to it. In 1910, more than half of the 262,000 workers in the southern lumber industry were Blacks who worked the lowest-paid, unskilled jobs. The lumber owners operated their businesses as feudal domains, “filling the towns with gunmen whom the authorities commissioned as deputy sheriffs, and jailing anyone who questioned their rule.”35

Since the AFL refused to organize them, a group of workers sympathetic to the IWW and the SP began organizing the Brotherhood of Timberworkers in 1911. The union opened its doors to Black workers, but organized them into separate locals in accordance with Jim Crow laws. Despite intense repression, lockouts, the blacklisting by the employers of several thousand workers, and efforts to divide workers along color lines, by early 1912 the union had a membership of around 25,000, half of whom were Black. The union decided that year to affiliate with the IWW, and invited Big Bill Haywood to speak at its convention in Alexandria, Louisiana. When Haywood arrived and was told that Black union members were meeting separately according to Louisiana law he replied:

You work in the same mills together. Sometimes a black man and a white man chop down the same tree together. You are meeting in convention now to discuss the conditions under which you labor. This can’t be done intelligently by passing resolutions here and then sending them out to another room for the black man to act upon. Why not be sensible about this and call the Negroes into this convention? If it is against the law, this is one time when the law should be broken.36

One of the IWW’s most prominent Southern organizers, Covington Hall, spoke up after Haywood, arguing: “Let the Negroes come together with us, and if any arrests are made, all of us will go to jail, white and colored together.” Later, Haywood and Covington addressed a mass meeting at the Alexandria Opera house to a completely integrated audience—a first for the city.37

The only weakness in the IWW’s impressive commitment to racial equality was its aversion, as a result of its singular focus on the class struggle, to organizing antiracist campaigns outside the workplace against the lynching, housing discrimination, denial of voting rights, and so on, that they so eloquently denounced.

Free speech fights

Immediately after the IWW found cohesion after its early faction fights, it became engaged in “Free Speech Fights” across the country, where union members were arrested for public agitation and began waging battles for the right to give street corner soapbox speeches.

These blew up quickly in various cities around the country, including Spokane, San Diego, and Fresno. The IWW responded with a tactic to make the costs of persecuting free speech quite expensive. IWW branches sent out calls across the country for their members to ride freight trains to the various cities where the free speech fights were taking place, to get arrested in turn and fill up the jails to make more arrests impossible. One such appeal from the IWW newspaper in 1909 read: “Quit your job. Go to Missoula. Fight with the Lumberjacks for Free Speech. . . Are you game? Are you afraid? Do you love the police? Have you been robbed, skinned, grafted on? If so, then go to Missoula, and defy the police, the courts and the people who live off the wages of prostitution.”38

In Spokane, the IWW waged a free speech fight throughout 1909 for the right to protest fraudulent job placement agencies and the ability to make speeches in favor of unionism. After the beginning of the year, the city council moved to outlaw public street corner speechmaking by “revolutionists,” at the behest of the local Chamber of Commerce. After having several members harassed and arrested, the local IWW put out the call:

The first day of the fight for free speech, man after man mounted the box to say “Friends and Fellow Workers” and be yanked down, until 103 had been arrested, beaten and lodged in jail. A legend runs that one man, unaccustomed to public speaking, uttered the customary salutation, and still un-arrested, and with no police by the box, paused, with nothing more to say, and in all the horrors of stage fright, hollered: ‘Where are the cops?’ In a month over 500 were in jail on bread and water.39

As the months wore on, more and more Wobblies rolled into Spokane to join the struggle for free speech and be arrested. Eventually, several hundred IWW members would be held at one time, stuffed eight or ten into jail cells built for three or four inmates. Despite a successful legal challenge by the IWW, the city fathers banned all public street meetings as well as indoor meetings, and sent police to raid the IWW hall and arrest all of its inhabitants, continuing in their attack on free speech. Spokane banned the publishing, sale, and distribution of the IWW newspaper and even arrested the newsboys who hawked it on the streets.

But the Wobblies held the line, giving educational meetings, agitational speeches and organizing revolutionary sing-alongs under brutal conditions inside the jail. After an initial lull during the summer, another wave of IWW members descended on the town in the winter of that year, continuing to make the ongoing imprisonment of roving agricultural workers as expensive as ever. Finally, in the early spring of 1910, the city sued for peace, caving in to virtually all of the IWW demands and ending their persecution of free speech.

Roger Baldwin, the founder of the American Civil Liberties Union and a sympathizer and one-time member of the IWW, recalled many years after the fact that the IWW “wrote a chapter in the history of American liberties like that of the struggle of the Quakers for freedom to meet and worship, of the militant suffragists to carry their propaganda to the seats of government, and of the Abolitionists to be heard. . ..The little minority of the working class represented in the IWW blazed the trail in those ten years of fighting for free speech [1908-1918] which the entire American working class must in some fashion follow.”40

This practice of “filling the jails” with cheering and singing migrant workers was later adapted to the needs of the civil rights movement in the South during the 1950s and 60s, but for the IWW, while courageous, the campaign took up precious resources and time to the detriment of organizing new shops.

Bread and roses

In 1912 the IWW made its first major breakthrough with the enormous textile workers strike in Lawrence, Massachusetts. Responding to a pay cut, local textile workers responded with a walkout, eventually bringing out 23,000 workers in Lawrence, roughly 60 percent of the town’s population. The IWW acted quickly and sent organizers to Lawrence to help their small local of 200 or so members organize and lead the spontaneous strike. With an elected strike committee of sixty delegates, representing each of the fifteen major ethnic populations and occupational groupings, the strike was a model for how to organize the immigrant working class.41 A song about the strike written by an immigrant “mill girl” gives a sense of the crosscultural solidarity pervading the strike:

In the good old picket line,

In the good old picket line,

The workers are from ev’ry place, from nearly ev’ry clime.

The Greeks and Poles are out so strong and the Germans all the time,

But we want to see more Irish in the good old picket line.

With the turn of the century, the demographics of the city’s labor force had undergone dramatic changes, shifting from a predominantly native-born workforce to an overwhelmingly immigrant milieu, comprised of Italians, Greeks, Portuguese, Russians, Poles, Germans, Irish, Lithuanians, Syrians and Armenians. Forced into shameful living conditions in squalid tenements, working a normal week of fifty-six hours for poverty wages (malnutrition was a particularly pernicious cause of death among the children of the mill hands) and almost entirely shunned by the AFL, the textile workers of Lawrence had long been expected to explode in angry rebellion, and the wintry month of January 1912 would prove to be the time.

A statement of the strikers explained their decision:

For years the employers have forced conditions on us that gradually and surely broke up our homes. They have taken away our wives from the homes, our children have been driven from the playground, stolen out of schools and driven into the mills, where they were strapped to the machines, not only to force the fathers to compete, but that their young lives may be coined into dollars for a parasite class, that their very nerves, their laughter and their joy denied, may be woven into cloth.42

The IWW sent a cunning and talented twenty-seven-year-old organizer, Joseph Ettor, to run the strike. Prepared for this battle by previous organizing experience in the western reaches of the IWW, Ettor led a brilliantly organized strike the likes of which had never been seen. Foner wrote of the Battle of Lawrence that

the strike committee was the executive board of the strikers, charged with complete authority to conduct the strike, and subject only to the popular mandate of the strikers themselves. All mills on strike and their component parts, all crafts and phases of work, were represented. The committee spoke for all workers. . ..The principle of national equality was also carried out in the sub-committees elected: relief, finance, publicity, investigation, and organization. Thus every nationality group had its own organization in the management of the strike, and complete unity was obtained for this working class machine through the general strike committee.43

The strikers shut down the mills from wall to wall, with no textiles able to be produced at any point throughout the walkout. Monster mass meetings were held every weekend throughout the nine-week strike, for the strikers to vote on and ratify the decisions made by the strike committee, facilitated by a small army of interpreters. Continuous mass pickets of thousands patrolled the mill area of the town, completely encircling each mill to ensure that no scabs were able to work. Any scabs who did manage to sneak into the mills were visited at their homes at night and persuaded not to return to work, or had the word “scab” painted in red across their doors in their native language. Massive parades took place every few days, with anywhere between 3,000 to 10,000 workers marching and singing the Internationale in their own languages. Ten thousand of the striking workers joined the IWW.

Facing armed militias paid for by the hostile mill owners, brutal police attacks, and widespread arrests of hundreds of strikers, as well as the leadership of the competing AFL textile workers union who came to Lawrence in an attempt to call off the strike, the IWW held out. Ettor was arrested after only three weeks in Lawrence, framed on a ludicrous charge (a policeman shot a teenage girl striker at a parade and Ettor was arrested for “inciting to riot,” though he hadn’t attended the parade), so Big Bill Haywood and Elizabeth Gurly Flynn were sent to carry through the rest of the strike.

Faced with the need to raise money and the relief committee’s struggle to collect enough food to operate the multiple free kitchens operating throughout the city, the strike committee decided to send the children of striking families out of Lawrence to stay with friendly host families in New York and around the Northeast. Newspapers carried stories and images of the malnourished and ragged children of the strikers across the country as they arrived at their new temporary homes, which played a role in tipping public opinion in favor of the strike. When Lawrence police attacked a delegation of the children on their way to the train station with their mothers, ruthlessly beating down and arresting children and parents alike, national outrage ensued, leading to an eventual Congressional investigation of the living and working conditions of the striking families.

With every innovative tactic used by the strikers, the mill owners and city leaders (oftentimes interchangeable) upped the ante. The state militia insituted martial law for a time, leading to the death of an eighteen-year-old Syrian mill hand (he was bayonetted in the back while running from advancing troops). Private detectives from the Pinkerton agency were brought into the town to spy on strike leaders, provoke riots, and terrorize families. Local clergy who would play ball were enlisted on the side of the mill owners, who instructed them to denounce the strike and the IWW. And, at the behest of the city council, the rival AFL union was brought in to attempt to end the strike by signing agreements for the skilled workers and sending them back to work.

The IWW kept calm and held out through all of these challenges to win a stunning victory, wresting pay raises of 5 to 22 percent to all of the striking workers, payment of overtime, and promises of no retaliation from the mill owners.

The Lawrence strike still holds the imagination of radicals today who want to build a multi-ethnic, fighting labor movement, as it certainly did in 1912. It is from the Lawrence strike that the slogan “Bread and Roses” arises, derived from a banner held by striking teenage immigrant women, stating plainly that they wanted not just bread, that is, the basic necessities of life, but roses too.

The success in the Lawrence strike launched the IWW into the national arena, with 1912 as the year in which they scored organizing victories in different industries across the country: on the railroads, in textiles, steel, lumber, metalworking, longshore jobs, agriculture, and even cigar rolling, once a bastion of AFL craft unionism.

It is in this period, between 1912 and the end of World War I, that the IWW made its most impressive gains in terms of membership and political impact among the American working class. Because of its willingness to organize women, people of color, the unskilled and foreign-born workers (oftentimes these overlapped), the IWW grew in numbers and influence.

In Philadelphia, the IWW organized longshoremen across color lines to win united multiracial strikes against the shipping bosses. In Louisiana, it organized lumber mill workers into integrated local unions, breaking Jim Crow segregation laws, a practice not accepted by other unions until decades later. They also organized migrant agricultural laborers in California and across the West, winning some gains in anticipation of later union drives among farm laborers in the 1930s and again in the 1960s and 1970s. Foreshadowing events during the Great Depression, the IWW organized unemployed workers to fight for their own interests and prevent scabbing, and also participated in a number of “sit in” strikes in various industries, including auto plants in the Midwest. During this period, at its height, the IWW could claim 40,000 dues-paying members.44

But there were still nagging political questions which remained unanswered. Even before 1912, Eugene Debs quietly let his membership in the IWW lapse because of his discomfort at the level of hostility from some quarters of the IWW toward members of the AFL. And the IWW was still losing plenty of strikes for every victory, as in the large Paterson, New Jersey silk strike which went down to defeat only a year after Lawrence, or the defeat of the rubber workers strike in Akron, Ohio. Was it a betrayal of revolutionary principle to set up permanent strike funds, so the IWW stood a chance of winning long strikes? Or to sign contracts with management? Within a year of their crowning victory in Lawrence, the IWW local declined from over 10,000 members to roughly 700, with most of their militants being driven out of the mills and blacklisted. Within the organization, rumblings could be heard that pointed to a different method, as storm clouds gathered on the horizon.

The war

The heyday of the IWW began to pass as major political developments played out on the world stage. World War I erupted across Europe in the fall of 1914, splitting the world socialist movement over support or opposition to the war. Instead of opposing the war or even taking strike action to cripple each country’s wartime mobilization, the various socialist parties of Europe lined up with their “own” governments and supported the war effort. The socialist parties of the Second International had failed the test of history.

With the coming US involvement in the war, the federal government began ramping up a Red Scare to use as a bludgeon against all radical forces across the country. The IWW was organizing and leading strikes in the industries pivotal to the war effort (copper mining, lumber, rubber, among others) and became a natural target for state repression. President Wilson’s propaganda machine turned out endless articles and proclamations equating the IWW with bomb-throwing saboteurs or paid agents of the German Kaiser intentionally trying to disrupt the American war effort.

Following their insistence that the IWW was “non-political,” the IWW anticipated the intensity of the Red Scare and in an effort to avoid open repression by the federal government, actually refused to take a public stance against US entrance into the war. While local unions, affiliated publications, and individual members were left free to express their opposition to the mad butchery of the imperialist war, the general executive board officially discouraged open agitation against the war and did not take any open position against it. Fred Thompson, former general secretary treasurer of the IWW wrote:

A minority [of members in the IWW] felt the IWW should concentrate on open opposition to the war.. . . The majority felt this would sidetrack the class struggle into futile channels and be playing the very game that the war profiteers would want the IWW to play. They contended that the monstrous stupidity by which the governments of different lands could put their workers into uniforms and make them go forth and shoot each other was something that could be stopped only if the workers of the world were organized together; then they could put a stop to this being used against themselves; and that consequently the thing to be done under the actual circumstances was to proceed with organizing workers to fight their steady enemy, the employing class. . .keeping in mind the ultimate ideal of world labor solidarity. There was no opportunity for referendum, but the more active locals took this attitude, instructing speakers to confine their remarks to industrial union issues, circulating only those pamphlets that made a constructive case for the IWW, and avoiding alliance with the Peoples Council and similar anti-war movements.45

Although radicals have long aimed to organize the entire world working class, the idea of only engaging in antiwar organizing through production-halting strikes once the entire global working class has been brought into the ranks of radical unions, can only be interpreted as an intentional avoidance of the issue of the war. As it turned out, however, the IWW could try to avoid “politics,” but “politics” would not ignore the IWW.

Despite their avoidance of taking a public antiwar stance, various states and the federal government went on the offensive against the IWW. Numerous state legislatures passed new “criminal syndicalism” laws, which would be used to prosecute hundreds of members of the IWW. And in September 1917, the Department of Justice raided forty-eight IWW halls across the country, arresting 165 leaders of the group in a single major operation and charged them under the newly passed Espionage Act. Of those arrested, 101 were convicted and given sentences of up to twenty years in prison, including some who had not been members of the IWW for years.46

And these were the lucky ones. Those who fared worse were attacked by lynch mobs recruited from local chambers of commerce, brutally beaten or murdered with the silent consent of the government. Frank Little, perhaps one of the IWW’s most outstanding organizers, was hung from a railroad trestle outside of Butte, Montana after being horribly disfigured. In Centralia, Washington on November 11, 1919, IWW member and army veteran Wesley Everest was turned over to a lynch mob by jail guards, had his teeth smashed with a rifle butt, lynched three times in three separate locations, his corpse then riddled with bullets, before being dumped in an unmarked grave. The official coroner’s report listed the victim’s cause of death as “suicide.”

Revolution

The other political development to be a major issue for the IWW was the birth of Soviet power in Russia and the Bolshevik Revolution at the end of 1917. Before the Russian revolution, radicals across the world had always looked back to the Paris Commune as a vision of what worker’s power might look like. Then, in 1917, in the most backward country of Europe, a revolution took place, sweeping aside the Tsar’s ministers, the generals, the landlords, and the factory owners. And it was a revolution led by a party that shared a vigorous disdain for the opportunistic reformism of the Second International that many in the IWW had always possessed. The Bolshevik Party was an organization which had earned its political leadership in thousands of strikes, mass protests, and rebellions, through hard years of underground activity and struggle.

The following November mutinies broke out in the German military, and workers engaged in mass strikes in Berlin, toppling the Kaiser’s government and ending the war. A worker’s government was established in Hungary. Mass strikes and factory occupations exploded across Italy in the “Biennio Rosso.” Revolution was literally sweeping the continent, inspired by the Russian example. With the formation of the Communist International in March 1919, and the split in the US Socialist Party with newly formed communist parties emerging from the fray, many of the IWW’s best leaders and workers decided to join and build the new parties along a Bolshevik model.

The political impact of the October Revolution is difficult to overstate, in that radicals the world over began to identify either with or against the Revolution. Big Bill Haywood was one of those who were immediately sympathetic to the victory of Bolshevism in 1917. In his autobiography, he recalled:

About this time a lengthy letter reached us addressed to the IWW by the Communist International. This letter spoke of the situation of capitalism after the imperialist war, outlined the points in common held by the IWW and the Communists, warned of the coming attacks on the workers, pictured the futility of reformism, analyzed the capitalist state and the role of the dictatorship of the proletariat and told how the Soviet state of workers and peasants was constructed. Such basic questions as “political” and “industrial” action, democratic centralization, the nature of the social revolution and of future society were gone into thoroughly. After I had finished reading it, I called Ralph Chaplin over to my desk and said to him: “Here is what we have been dreaming about; here is the IWW all feathered out!47

After being arrested under the Espionage Act, Haywood fled his bail and boarded a ship for the Soviet Union. James Cannon was one of the founding members of the Communist Party, as well as Jack Reed. Elizabeth Gurley Flynn joined a few years later. William Z. Foster hadn’t been in the IWW for ten years because of his opposition to dual unionism and his attachment to the policy of “boring from within” established unions, but he soon joined the new CP as well. Even Lucy Parsons, widow of a Haymarket martyr and perhaps the most sympathetic to anarchism, went on to join the CP in the mid-1930’s.

Revolutionary unionism?

While the prestige and appeal of a successful revolution certainly played a role in attracting American radicals to the CP, much of the process of winning members to the new party revolved around tough political debates and questions, argued out and voted on in the sessions of the Communist International. Central to this for the US Left was the question of revolutionary unions and the method of Communist involvement in the labor movement. Taken up by Lenin in the 1920 pamphlet “Left Wing” Communism: An Infantile Disorder and published for the Second Congress of the Comintern, Lenin hammered the strategy of creating rival unions with established trade unions in response to the reactionary character of labor officials, even citing Samuel Gompers specifically:

To refuse to work in the reactionary trade unions means leaving the insufficiently developed or backward masses of the workers under the influence of the reactionary leaders.. . . If you want to help the masses and to win the sympathy, confidence and support of the masses, you must not fear difficulties, you must not fear the pin-pricks, chicanery, insults and persecution of the “leaders”. . . but must imperatively work wherever the masses are to be found.48

Lenin’s contribution to the debate over the future of the CP in the US labor movement, and its subsequent ratification by the Second Congress of the Comintern, steered the young American CP towards participation in the mass movements of their time. Directing much of his theoretical fire at one of the central premises of the IWW, that the AFL was beyond redemption in large part because of the top leadership’s belief in “industrial harmony” and “labor management cooperation,” Lenin (and others like Karl Radek and Gregory Zinoviev, in the Trade Union Commission) within the Comintern pushed the new CP into working within established unions to fight for better wages and conditions, as well as against the oftentimes reactionary leadership of the labor bureaucracy, and not abandoning the rank and file to the politics of the Samuel Gomperses of the labor movement.

Faced with massive persecution by all levels of government and an exodus of many of their best leaders and cadres, the IWW began to decline. The organization split in 1924, hemorrhaging members in the process. By 1930, the IWW had dwindled to below 10,000 members, and as the working class upsurge of the decade exploded across the national arena with the rise of the CIO, the IWW continued to lose numbers. Indeed, the CIO (organized by many former Wobblies who joined the CP) would quickly take the last few remaining locals of the IWW, which, because of its refusal to sign contracts, allowed the CIO to easily win over entire locals to its own powerful and growing new industrial unions. The last significant membership base was concentrated among metal workers in Cleveland, who wound up splitting away and going into the CIO.49

Conclusion

James P. Cannon, former organizer for the Marine Transport Workers Union of the IWW and the founder of American Trotskyism, gave a lecture on the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the IWW in 1955. Cannon praised the IWW but also recognized the problems it had trying to build an organization that had features of both a union and a revolutionary organization. Whereas unions, as the basic fighting forces of the working class, are only effective when all workers in a given trade or industry are embraced in their ranks regardless of whether each individual worker believes in the political principle of class struggle, revolutionary groups are effective when their own membership maintains a high degree of political agreement and clarity, enabling the group or party to operate with effective flexibility and coherence:

One of the most important contradictions of the IWW, implanted at its first convention and never resolved, was the dual role it assigned to itself. Not the least of the reasons for the eventual failure of the IWW—as an organization—was its attempt to be both a union of all workers and a propaganda society of selected revolutionists—in essence a revolutionary party. Two different tasks and functions, which, at a certain stage of development, require separate and distinct organizations, were assumed by the IWW alone; and this duality hampered its effectiveness in both fields. . . .

The IWW announced itself as an all-inclusive union; and any worker ready for organization on an everyday union basis was invited to join, regardless of his views and opinions on any other question. In a number of instances, in times of organization campaigns and strikes in separate localities, such all-inclusive membership was attained, if only for brief periods. But that did not prevent the IWW agitators from preaching the revolutionary overthrow of capitalism in every strike meeting. . . .

In truth, the IWW in its time of glory was neither a union nor a party in the full meaning of these terms, but something of both, with some parts missing. It was an uncompleted anticipation of a Bolshevik party, lacking its rounded-out theory, and a projection of the revolutionary industrial unions of the future, minus the necessary mass membership. It was the IWW.50

Yet it must be said that in its day the IWW was the most advanced working-class organization the United States had yet produced. The IWW wrote one of the most inspiring and brilliant chapters of the workers movement in the United States. A forerunner of events to come, the legacy of the IWW contains much that is imperative for the contemporary labor movement to relearn, with its rejection of racism and anti-immigrant sentiment, its emphasis on building power on the shop floor through the mobilization of the rank and file, and its radical appeal to the urgency and necessity of solidarity. And beyond this, in the words of Cannon, it was “a revolutionary organization whose simple and powerful ideas inspired and activated the best young militants of its time, the flower of a radical generation. That, above all, is what clothes the name of the IWW in glory.51”

Suggestions for further reading

Philip S. Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States, Vol. 4 (New York: International Publishers, 1965).

Melvyn Dubofsky, We Shall Be All: A History of the Industrial Workers of the World, abridged ed. (University of Illinois Press, 2000).

Sharon Smith, Subterannean Fire, A History of Working Class Radicalism in the United States (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2006).

Vladmir Lenin, “Left Wing” Communism: An Infantile Disorder (New York: International Publishers, 1989).

James P. Cannon, “The I.W.W.,” The Fourth International, Summer 1955.

Hal Draper, Marxism and the Trade Unions.

Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, The Rebel Girl: An Autobiography (New York: International Publishers, 1973).

- Lucy Parsons, “Third Day Afternoon Session, The 1905 Proceedings of the Founding Convention of the IWW,” http://www.marxists.org/history/usa/unio...

- Wobblies was the common slang term to describe members of the IWW.

- Paul Frederick Brissenden, The IWW: A Study of American Syndicalism (New York: Columbia University, 1920), 352.

- Delegate Charles Kiehn, “Sixth Day Morning Session, The 1905 Proceedings of the Founding Convention of the IWW,” http://www.marxists.org/history/usa/unio...

- Fred Thompson, The IWW: Its First Seventy Years (Chicago: Industrial Workers of the World, 1976), 23.

- Preamble in Brissenden, The IWW, 351.

- Sharon Smith, Subterranean Fire: A History of Working Class Radicalism in the United States (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2006), 67.

- Philip S. Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States, Vol. 3 (New York: International Publishers, 1964), 195.

- Ibid., 202.

- Ibid., 150.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., 139.

- Ibid., 235.

- Ibid., 221.

- Smith, Subterranean Fire, 74.

- James Weinstein, The Decline of Socialism in America, 1912-1925 (New York: Vintage Books,1967), 7.

- Melvyn Dubofsky, We Shall Be All: A History of the Industrial Workers of the World (New York: Quadrangle/The New York Times Book Co.,1973), 135.

- Philip Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the United States, Vol. 4: The Industrial Workers of the World 1905–1917 (New York: International Publishers, 1997), 99, 103–111.

- Ibid., 108.

- Thompson, The IWW: Its First Seventy Years, 40.

- Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the US, Vol. 4, 137.

- Ibid.

- Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the US, Vol. 4, 70.

- Ibid., 60-61.

- Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the US, Vol. 4, 168.

- Stewart Bird, Solidarity Forever: An Oral History of the IWW (Chicago: Lake View Press, 1985), 67.

- Dubofsky, We Shall Be All: A History of the Industrial Workers of the World, 24.

- Ibid., 25.

- Quoted in Ralph Darlington, Syndicalism and the Transition to Communism: An International Comparative Analysis (Hampshire, UK: Ashgate Publishing, 2008), 97.

- Philip Foner, “The IWW and the Black Worker,” The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 55, No. 1 (Jan., 1970).

- John Riddell, Lenin’s Struggle for a Revolutionary International (New York: Monad Press) 1986, 17.

- Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the US, Vol. 4, 123.

- Ibid.

- Justice for the Negro: How Can He Get It? (1919), available on line at http://libcom.org/library/justice-negro-....

- Foner, “The IWW and the Black Worker.”

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the US, Vol. 4, 173.

- Thompson, The IWW: Its First Seventy Years, 48-49.

- Ibid., 173.

- Thompson, The IWW: Its First Seventy Years, 55.

- Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the US, Vol. 4, 313.

- Foner, History of the Labor Movement in the US, Vol. 4, 318.

- Thompson, The IWW: It’s First Seventy Years, 79.

- Thompson, The IWW: Its First Seventy Years, 114-115.

- “Government Suppression,” 2012, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Industrial_...

- William D. Haywood, The Autobiography of Big Bill Haywood (New York: International Publishers, 1977), 360.

- V.I. Lenin, “Left-Wing” Communism, An Infantile Disorder (New York: International Publishers, 2009), 36-37.

- Thompson, The IWW: Its First Seventy Years, 196.

- James P. Cannon, “The IWW,” 1955, http://www.marxists.org/archive/cannon/w...

- Ibid.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Google+

Google+ Tumblr

Tumblr Digg

Digg Reddit

Reddit StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon