It can’t happen here?

The first article in this series (ISR 85, Sept.–Oct. 2012) focused on the struggle against the Silvershirts in Minneapolis.1 Part 2 focuses on the struggle against the German American Bund and the Christian Front in New York City.

IN DISCUSSIONS with his supporters in the United States, Leon Trotsky stressed the need to create union-based defense guards as a central aspect of a strategy for fighting fascism. This policy was implemented in only one city—Minneapolis, Minnesota—for a short period of time in the late summer and early autumn of 1938. Trotsky had hopes that the Teamsters Local 544 Union Defense Guard (UDG) could become a model for organizing against the resurgent fascists to “show the entire country.”2 Unfortunately, the Socialist Workers Party didn’t have a base of support or the leadership of a local union anywhere else in the United States that approached that of Teamsters Local 544. The broad Left and the left wing of the union movement, particularly the new militant unions of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), were led by or heavily influenced by the much larger (and thoroughly Stalinist) Communist Party (CP), whose antifascist organizing was of an altogether different character.

In September 1933, eight months after Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany, the CP founded the American League against War and Fascism.3 However, it was only after the Seventh (and last) Congress of the Communist International in 1935 that its parties were instructed to make the primary focus of Communist political work the formation of “popular or people’s fronts” against fascism.4 If in the previous period the CP had pursued a policy of ultraleft denunciation of all reformist and social-democratic parties as “social-fascism,” this new turn lurched in the other direction, marking a sharp right turn toward making electoral alliances with reformist parties of the Left and parties of the capitalist class. The revolutionary rhetoric of the Communist movement was tossed aside in favor of the nationalism and patriotism of their respective capitalist countries. For example, Earl Browder, the general secretary of the CPUSA, proclaimed that “Communism was twentieth-century Americanism.”5 Underlying this shift in political strategy was Russia’s search for a military alliance against Nazi Germany, what became known as “collective security.”6 In line with this change, the CP in the United States moved from sweeping denunciations of Roosevelt as a “social-fascist” to uncritical support for Roosevelt’s New Deal. For CP-allied groups like the league, though a very vigorous organization, it meant judiciously avoiding any activities that might make their Democratic Party allies blush with embarrassment. The league concentrated on education, lobbying, and peaceful and legal picketing with a heavy dose of pro-American rhetoric to counter domestic Nazis, fascists, and their apologists.

As the decade progressed, and as the fascists grew bolder, the tame tactics of the league appeared more and more out of touch with reality. A political space opened up for those who wanted to pursue more militant actions, including people who came to league-sponsored demonstrations, particularly against the most open admirers of Hitler in the United States, the German American Bund. When it came to the largest anti-fascist mobilization of the era—against the Bund at Madison Square Garden in February 1939—the CP and its allied organizations were absent.

The German American Bund

The German American Bund emerged by the late 1930s as “the largest and best-financed Nazi group operating in America,” according to historian Warren Grover.7 Its national membership peaked at around 25,000 members.8 This was largely due to efforts of its leader Fritz Kuhn. Kuhn fought in the German Army in World War I, and when the war was over he joined the Freikorps, the paramilitary group of demobilized army veterans that violently suppressed the revolutionary workers movement in the early days of the German Republic. He joined the Nazi Party while a student at the University of Munich.9 When Kuhn assumed the leadership of the Bund in 1936, he was forty years old and had only been in the United States for eight years, having become a naturalized citizen in 1933. Like many aspiring Nazi leaders of the era, Kuhn tried to imitate Hitler in every way (excluding the mustache) even calling himself the “American Fuhrer.”10 Despite the many formidable obstacles to building a fascist movement wearing the swastika in the United States, Kuhn pressed ahead. As the decade wore on, the more diffuse and incipient native fascist currents were drawn into the orbit of the better-organized Bund.

The Bund modeled itself on the Nazi Party, with Kuhn as undisputed leader. His official title was Bundesleiter. The Bund created its own version of Hitler’s SS—the Order Division (OD)—whose members swore a personal allegiance to Kuhn. Bundists, as they were called, wore uniforms also inspired by the SS—a silver-gray shirt, a Sam Browne belt, black trousers, black shoes—with a swastika usually worn as a pin rather than an armband. The Bund established a number of training camps, including Camp Nordland in New Jersey, Camp Siegfried on Long Island, New York, and Camp Highland in upstate New York. Their rallies were festooned with Nazi and US flags, and began with the singing of the “Horst Wessel song,” the anthem of the German Nazi Party. Once the chorus ended, all would give the fascist salute and shout in unison “Heil Hitler, Heil America!” The main speaker, usually Kuhn or his personal representative, would come to the microphone and shout “Free America” and the audience would return the call. Freeing America meant freeing it from “Jewish domination.” Anti-Semitic and Nazi literature was bountiful at meetings and rallies, and after 1936, Father Couglin’s Social Justice magazine was conspicuously present. The Bund’s first official announcement declared that its purpose was “to combat the Moscow-directed madness of the red world menace and its Jewish bacillus-carriers.”11

According to historian Warren Grover, between 1936 and 1939 “[t]he Bund gained an increasingly prominent spotlight in the United States.” Its leadership, however, remained “largely in the hands of German immigrants who had recently become US citizens or were becoming citizens so they could specifically work for Nazi Germany.”12

For six months in 1937, the Chicago Daily Times had a team of three reporters assigned to investigate the Bund.13 John C. Meltcalfe’s fourteen-part diary of his experiences—“I Am A U.S. Storm Troop”—was serialized in the Daily Times for two weeks straight in September 1937. “We are not plotting a revolution,” a Bund leader was recorded as saying. “But we are going to be prepared to wrest control from the communist-Jews when they start their revolution. We will save America for white-Americans.”14 The Daily Times exposé, along with government investigations, fixed an image of the Bund in the minds of many people as a barely concealed army waiting for the right moment to strike. After the Munich sellout to Hitler, Kuhn and the Bund faced increasingly angry and militant crowds who were scrapping for a fight. This became glaringly evident the night of October 1, 1938—the day Germany annexed the Sudetenland—when thousands turned out to protest a Bund rally in Union City, New Jersey, and sent Kuhn running into the night for his life.

Union City and Chicago: Scenes from the frontlines

Kuhn was scheduled to speak at the local Bund meeting in Union City, a medium size industrial city with a large Irish and Italian population in Hudson County, New Jersey. The Bund meeting was held in the back of a building adjoining the City Hall Tavern, a well-known bar in downtown Union City. Kuhn arrived at 5:30 p.m. dressed in his Bund uniform. He was easy to spot. A lookout for the American League for Peace and Democracy (ALPD—a CP front organization) saw Kuhn enter the hall, and signaled to others to start the demonstration. Nancy Cox a prominent anti-Nazi campaigner led this phase of the demonstration. Soon a crowd of about seventy-five people, ranging in age from fifteen to twenty years old, raised banners reading “Nazis Love War, Americans Love Peace” and “Fritz Kuhn Fights the Bill of Rights.” They started picketing the meeting hall. Kuhn was in the hall for about forty-five minutes as the demonstration and crowd of onlookers—about five hundred to seven hundred people—began to gather across the street. Soon the crowd began to spill over into the street, and the league organizers decided to lead a demonstration to the side entrance of the building, chanting “Hitler Wants Peace, Piece by Piece” and “Deport Fritz Kuhn.”15

Then a squad of veterans from the Andrew Jackson Veterans Democratic Club arrived on the scene. They had been holding their own meeting, according to the New York Times, across from the City Hall Tavern, waiting for the Bund to arrive.16 The leadership of the demonstration shifted quickly from Cox and the ALPD to the veterans. Other veterans soon joined the crowd from the American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign Wars.17 Union City police chief Harry Jenkins led a contingent of seventy-five local cops to protect the Bund, but as the crowd swelled to five thousand people, it became very clear that the police were going to be overrun. Around 5:45 p.m., a squad of veterans pushed through the league demonstrators and the police line protecting the meeting hall. Five or six veterans got onto the steps of the building and into the entranceway before uniformed Bund members and cops tossed them out. The veterans regrouped across the street and then made another dash for the door. The cops, however, were prepared this time and stopped them in the middle of the road. The Union City cops then demanded a membership card from anyone who wanted to attend the Bund meeting.18 While the police were battling the veterans on the street, a large number of people began gathering on the rooftops surrounding the meeting hall, arming themselves with bricks, stones, or whatever else was available to do some physical harm to the Bundists. Down on the street, a paper and straw effigy of Hitler was carried into the crowd and burned.

Time was running out for Kuhn. Chief Jenkins went into the hall and told Kuhn that he needed to leave the area and that the police would protect him. Jenkins told them to bring Kuhn’s car around to the side entrance. “Do you give me that order?” Kuhn demanded. “No,” Jenkins told him, “it’s a request from me. We’ve been decent to you and now let’s get out of here before there is trouble.” Then an emissary from the veterans arrived and told him “if this place isn’t closed in half an hour we’re going in there and close it.” Suddenly, a brick crashed through the window scattering glass over the floor, very close to the table where Kuhn was eating. A young Bund guard rushed to pull the shade. “Sit down,” Kuhn barked at him. “Don’t get excited.” He was beginning to panic but chose to put on a brave face for his troops. “I would not leave for nothing,” he declared. “Not for 5,000 Communists. I wouldn’t run away from 10,000.” When someone told him that there actually were 5,000 people outside, he quickly changed his mind. The moment he stepped outside the door, a deafening roar of boos came from the angry crowd, along with “Kill him!” and “Run him out of town!” Kuhn fled Union City and went to speak at more sympathetic venues in New Jersey and New York that night. The New York Times reported, “The local bund members made no attempt to hold their meeting, those in uniform donning civilian clothes before they left.”19

Two weeks later on October 16, Kuhn got a similar reception in Chicago, when “more than 3,000 protesting men, women and children stormed a meeting. . .of the German-American Bund in the Lincoln Turner Hall, 1005 West Diversey Parkway,” the Herald and Examiner reported.20 The Bund was rallying to celebrate Hitler’s conquest of the Sudetenland. Fifty cops were assigned to protect the meeting. When demonstrators arrived, they carried signs that read, “Save Czechoslovakia and Democracy,” “Stop the Fascist Cancer,” and “Down with Fascism.” One anti-Nazi demonstrator displayed a handmade poster of Hitler’s face attached to the body of a pig with “Portrait of a Dictator” written on it. The German American League for Culture (GALC) called the protest. Its national secretary was Dr. Erich von Schroetter, a German émigré who had taught at Northwestern University in nearby Evanston. The GALC was the largest anti-Nazi organization in the German American community.21 But numbers far beyond the membership of the GALC responded to the call, including members of Chicago’s Communist Party and veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, who had just returned from fighting Franco in Spain. The meeting was supposed to begin at five o’clock but many of the Bund members and supporters got there earlier and the hall was filled by three o’clock. The early turnout probably was an effort to avoid anti-Nazi demonstrators.

Undaunted by the early turnout of the Bund and large police presence, four members of the GALC rushed Turner Hall carrying banners in German that read, “Let not yourself be betrayed. Fight against Fascism.” They fought Bund OD men in the hallway; other demonstrators jumped into the fight, and it turned into a massive street brawl. The police called for reinforcements, and one hundred cops marched from the Sheffield Avenue station half a block away. The police waded into the crowd, wielding their clubs and pushing the crowd away from the entrance to the hall, while demonstrators pushed back and scuffled with police, chanting, “Down with Nazis.” The cops cleared Diversey Parkway, but Nazi latecomers to the rally felt the fury of the crowd. “Two women started a near-battle when they walked toward the hall, shouting ‘Hurray for Hitler,’” reported the Herald and Examiner. “Several policemen surrounded them to escort them to safety—while other women tried to seize their clothing and tear their hair. Somewhat disheveled, the two quickly ran into the hall.”22 Then a dozen Bund members in uniform carrying swastika flags came goose-stepping down the street with their arms raised in the straight-armed fascist salute, crying, “Heil Hitler.” The demonstrators heckled, jeered, and insulted them as they passed through police lines into the hall. Four uniformed members of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade carrying the American flag and the flag of the Spanish Republic led a contingent of one hundred people, singing the “International,” and tried to crash the police lines, but were pushed back by police.23 “From the windows of the hall there came,” the Herald and Examiner reported, “faint snatches of three songs with which the bund meeting was opened. They were the ‘Star-Spangled Banner,’ the Nazi ‘Horst Wessel’ song and ‘Deutschland Uber Alles.’ The street throng sang the National Anthem.”24

Inside the hall, Fritz Kuhn spoke to three hundred of his followers. It was the second time in as many weeks that he had been confronted by huge crowds attempting to shut him down. Three weeks later, Nazi savagery was taken to another level of barbarism, and anger turned to fury and an aching desire for revenge against the Nazis.

Kristallnacht

On November 7, 1938, Herschel Grynszpan, a seventeen-year-old Jewish boy, walked into the German embassy in Paris. He asked to speak to the ambassador, Count Johannes Von Welczeck. Soon Ernst Vom Rath, the third secretary to the German ambassador, appeared instead.25 Grynszpan pulled out a pistol, fired, and mortally wounded him. The French police descended on the embassy and arrested Grynszspan. He shouted out, “Being a Jew is not a crime!” “I am not a dog! I have a right to live and the Jewish people have a right to exist on this earth. Wherever I have been I have been chased like an animal.”26 His family had been deported, along with ten thousand other Jews of Polish ancestry, to the Polish-German border in boxcars and dumped into a no-man’s-land without food, shelter, or sanitation.

The Nazis thought that Herschel Grynszpan had provided them with an opportunity.27 That opportunity was Kristallnacht (“the night of broken glass”), a pogrom ordered by Hitler and led by his propaganda minister Joesph Goebbels, which resulted in the deaths of dozens of Jews, the destruction of almost two hundred synagogues, the looting and burning of Jewish stores and apartments, and the internment in concentration camps of twenty thousand Jews. 28 It was the most savage assault yet on the already besieged German Jewish community, raising Nazi cruelty to a new level.

On top of this state-sponsored murder and destruction, the Nazis imposed a crushing $400 million “fine” on the Jewish community. US public opinion and the press were virtually unanimous in condemning Kristallnacht with nearly 94 percent of Americans in one poll disapproving of Germany’s treatment of Jews.29 If the Nazis thought this was a propaganda opportunity. it massively backfired on them. Meanwhile in Paris, it was announced that Grynszpan would stand trial for murder.30

One week after Kristallnacht, Dorothy Thompson rushed to Grynszpan’s defense. Thompson was, at the time, one of the most famous female journalists in the United States, if not the world. Her On the Record column was read by more than ten million people and carried by more than 170 papers.31 She took to the airwaves to appeal for a “fair trial” for Grynszpan.32 She recounted the horrible torment of his family as well as the millions tormented by the Nazi regime. Thompson then asked:

Who is on trial in this case? I say we are all on trial. I say the Christian world is on trial. I say the men of Munich are on trial, who signed a pact without one word of protection for helpless minorities.

We who are not Jews must speak, speak our sorrow and indignation and disgust in so many voices that they will be heard. This boy has become a symbol, and the responsibility for his deed must be shared by those who caused it.33

Seven million people heard her broadcast that night, and the response, according to one of her biographers Peter Kurth, was “phenomenal and she found herself directing the creation of an international fund for the defense of Herschel.” In the first few weeks nearly $40,000 in donations poured in.

She was joined in this enterprise by some of the most prominent figures in journalism, including John Gunther, Leland Stowe, editor Hamilton Fish Armstrong, Heywood Broun, Edgar Mowrer, Ramond Swing, and William Allen White; the Journalists’ Defense Fund set up offices on Fifth Avenue in New York, dedicated to Grynszpan’s defense in particular and to the relief of Hitler’s victims the country.34

Another voice was also heard on the radio, that of Father Charles E. Couglin, and it gave a very different message to millions of people. The Canadian-born priest of Irish ancestry, Coughlin emerged from being a little known priest in Royal Oak, Michigan, to having an audience of tens of millions of listeners on the radio in the early 1930s. Coughlin was tailor-made for radio with his rich baritone voice and an Irish brogue that he employed for great theatrical effect. He became famously popular after the Wall Street crash of 1929 by attacking the “banksters” (a conflation of bankers and gangsters). When asked about the future of the country after the 1936 election, he replied, “I’ll take the road to fascism.”35 And he did.

Coughlin took to the airwaves on Sunday afternoon on November 20, eleven days after Kristallnacht and six days after Thompson’s broadcast. His sermon was highly anticipated. Coughlin’s biggest audience was in the New York area over AM radio station WMCA. He began by posing three questions: “Why is there persecution in Germany today?” “How can we destroy it?” Why is “Nazism so hostile to Jewry?” He answered: Nazism was a “defense mechanism against Communism,” and that the “rising generation of Germans regard Communism as a product not of Russia, but of a group of Jews who dominated the destinies of Russia.” He downplayed the theft of $400 million from German Jews by the Nazis claiming, “Between the same years not $400 million but $40 billion. . .of Christian property was appropriated by the Lenins and Trotskys. . .by the atheistic Jews and Gentiles.” Coughlin cited a British government report that ridiculously claimed that the banking firm of “Kuhn Loeb & Company of New York, among those who helped finance the Russian revolution and Communism.” He finished with a voice dripping with “sarcasm and facetiousness,” according to sociologist and Coughlin biographer Donald Warren: “By all means let us have the courage to compound our sympathy not from the tears of Jews, but also from the blood of Christians—600,000 Jews whom no government official in Germany has yet sentenced to death. [My emphasis]”36

Coughlin’s “sermon” was outrageous, and the public backlash was strong. He admitted that “Nazi sources” were used for his sermon.37 The New York Times correspondent in Berlin reported, “Father Coughlin is, for the moment, the new hero of Nazi Germany.”38

“They are described as being pro-Jewish”

Kristallnacht produced a new organization mostly comprised of young Jewish men in Chicago, aching to take revenge for Hitler’s crimes. The press dubbed them “the nameless organization.” “Police were informed that a nameless organization of about 1,000 young men has been formed to oppose the two groups [the Silver Shirts and the German American Bund],” reported the Chicago Daily Tribune. “These men operate, it is said, in the manner of vigilantes, with word of mouth for action passing from mouth to mouth. They are described as being pro-Jewish.”39 They appeared on the streets in the weeks following Kristallnacht, and they struck hard and fast, and their confidence grew quickly. Their goal—from their actions—was the destruction of the Nazi presence in Chicago. Their first target was the Silver Shirts.

Three days after Coughlin’s radio sermon, the Silver Shirts scheduled a public meeting at the Engineer’s Building at 205 West Wacker Drive in Chicago. The Chicago Daily Tribune reported that, “A clique of objectors, it was reported to the police, influenced the management of the building to return the Silvershirts’ deposit for the rental hall.” What form the “influence” took, we can only guess. Stupidly the Silver Shirts posted a sign redirecting attendees to a nearby tavern, where 150 gathered to listen to their “Field Marshall” Roy Zachary, who ranted about how “Jewish financial interests” control the country and pledged the use of armed force to aid the police in crushing “a Communist-Jewish revolution.”40

While the Silver Shirts listened in rapt attention to Zachary, one hundred or more anti-Nazis gathered outside. “They wrenched open the doors, daring the Silvershirts to come outside. Their hoots and catcalls attracted a crowd of several hundred. As the meeting concluded the first Silvershirts to emerge were met at the door with blows and curses and the free for all ensued.”41 The Chicago Daily Tribune reported, “The Silvershirts’ opponents, many of whom were Jewish, appeared to have no particular organization. One of those who urged them on from a perch on an automobile running board was Edward Lytton, 27 years old.”42 This appears to be the first action carried out by the “nameless organization.” Among those who attended the Silver Shirt meeting was Bernard Voss, who called himself a “retired lecturer and teacher,” and claimed to have attended out of “curiosity.”43 He was beaten by six anti-Nazis as he fled the meeting. Four anti-Nazis, among them Edward Lytton, and one Silver Shirt were arrested that night.

Two days later, the nameless organization struck again. This time their target was the German American Bund. On Friday night, the Bund was scheduled to hold a film showing and lecture at the German House Tavern at 5100 block of South Ashland Avenue in Chicago. The scheduled film was “The Meaning of Nov. 9, 1923,” the date of Hitler’s failed Beer Hall putsch, and the lecturer was to be Dr. Otto Willumeit, one of the leaders of the Chicago Bund. Five hundred to one thousand anti-Nazis stormed the meeting. “Rocks and bricks crashed through windows, a door was removed from its hinges, a brick smashed through the skylight and several men were beaten severely.”44 Inside the meeting was none other Roy Zachary. “Don’t tell those Jews outside I’m here,” the Daily Times reported him pleading. “My life wouldn’t be safe.”45 Over one hundred cops arrived, bringing along a fire truck ready to spray anti-Nazi demonstrators. The battle continued out in the street. There is a photo in the Daily Times showing eight young men gleefully burning a Nazi flag. Neither film nor the lecture took place. “Bund members were given safe conduct from the district in patrol wagons.”46

Roy Zachary didn’t seem to get the message. The “nameless organization” wasn’t going to allow the Silver Shirts or the Bund to hold public meetings in Chicago. Despite being present at two meetings that were smashed up in the previous week, the Silver Shirts decided to hold another meeting, this time trying to conceal it from public attention. The invitation read: “Closed meeting for men only. To (name). You are invited to attend an address whose current important national matters will be treated by a well known speaker at 5835 Irving Park Blvd., Monday evening, Nov. 28 at 8 p.m.”47

One hundred Silver Shirts gathered at the meeting site to hear Zachary speak on “The Constitution of the United States,” the usual cover for his anti-Semitic rants. Shortly after he started to speak, a convoy of one hundred cars, carrying five hundred people in all, arrived and parked far enough away so as not to be spotted by Silver Shirt guards or lookouts. “At 8:35 p.m., as Zachary was in the midst of his speech, the doors of the meeting hall flew open. A shouting mass of men charged in. In another moment, fists were landing on noses and eyes. A general melee followed. Men were knocked down and kicked. A riot call was sent out to the police.”48 Reihold J. Dobbertin, who said he was there out of “curiosity,” later told the police, “While we were at the meeting, a mob suddenly broke open the front door, tearing it off its hinges. A group armed with rubber hoses, baseball bats and sticks rushed in and started beating everyone in the place.”49 Zachary was beaten down on the speaker’s platform and suffered cuts and bruises to the head. Another of the meeting attendees, Clarence Sutherland, suffered a fractured skull.50 “The meeting was the fourth assembly of Silver Shirts or the German-American Bund to be broken up violently in recent weeks,” according to the Chicago Daily Tribune.51

The nameless organization disappeared as quickly as it appeared on the scene after Kristallnacht. It personified the desire for militant action against American Nazis, but because a larger institution didn’t support them, they couldn’t sustain their activities. The political heat was certainly building on the Silver Shirts and the Bund, yet the Bund persevered, lifted by Hitler’s victories and the looming prospect of a fascist triumph in Spain. The Bund decided to make a play for the political big leagues, and announced that it would be holding a mass rally on George Washington’s Birthday. In the face of this bold challenge, who would organize a mass counterdemonstration against them?

“Don’t Wait—Act Now!”

Madison Square Garden, or the “Garden” as everyone called it, was by the late 1930s the most famous sports venue in the world. It was especially known for its boxing matches that were broadcast worldwide, but it also hosted political conventions, circuses, and was the site of many different types of political events over the years including pro- and anti-Nazi rallies.52 It held a special place in the minds of New Yorkers and Americans. To hold an event at the Garden bestowed a certain legitimacy on any event, and the ability to “fill” or not “fill” the garden was a sign of success or failure. So when the German American Bund announced that they would hold a “Pro-American Rally” on Washington’s birthday (they considered Washington to be “the first fascist”53), it produced a mixture of panic and anger. Historian Sander Diamond writes,

No event in the history of the Bund movement made more obvious to a nationally conscious America the Nazi threat at home than did the widely publicized Pro-American Rally in Madison Square Garden on February 20, 1939. The Nazi menace was no longer viewed as an abstraction—a concoction of the Jews, the refugees, the Left, or the German haters; it was no longer merely a European concern.54

The planning for the largest fascist mobilization of the era began in November 1938, when Bund events were under siege in many cities and the Bund was low on funds. It had recently bought a tavern in the predominately German neighborhood of Yorkville in Manhattan. Initially, many other far right, anti-Semitic organizations wanted in on the Garden rally. This motley crew included Donald Shea’s National Gentile League, the American Nationalist Party, the Crusaders against Communism, and the Christian Social Justice Party. Kuhn, however, decided it would be solely a Bund-sponsored event.55

The Garden was not owned by the City of New York, but it had a big say in whether an event could take place there or not. Initially, New York Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia came under some pressure to cancel the event, but he (and the American Civil Liberties Committee) “answered that it was the Bund’s prerogative to exercise its civil rights.”56

The Communist Party was the most likely organization to organize a counterdemonstration. The CP had its national headquarters in Union Square, and had nearly twenty thousand members in New York, plus a much wider circle of supporters. It led the anti-fascist American League for Peace and Democracy, and some of its members had fought and died in the Spanish Civil War. Yet it did nothing. In a interview in the “Questions from the People” column of the Daily Worker that appeared three weeks after the Bund event, V.J. Jerome,57 the editor of The Communist, the CP’s theoretical journal, responded to the criticism of the CP’s non-involvement saying that “the Communists could not undertake to forcibly prevent such a meeting once the City Administration had allowed it.” Such a course, Jerome argues, “would have incited a direct collision not only with the Bund, but with the city administration and the police.” Jerome noted that even peaceful picketing was ruled out by the CP. “A simple realistic view of the facts make it obvious that such peaceful picketing would be an immediate target for the combined provocations of the Trotskyites and their companions in arms, the Bundists. The net result would be the same danger as before, feeding the Nazi objective of collisions between the Bund and the vanguard of the democratic forces.”58

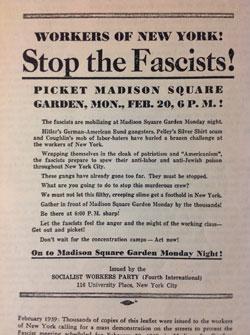

In the vacuum left by the CP, the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) put itself forward as the main group organizing against the Nazi rally. The SWP had many talented people and was well known for its leadership of the 1934 Teamster strikes in Minneapolis. Its Minneapolis branch had also done an exemplary job at running Pelley’s Silver Shirts out of Minneapolis the previous autumn. The SWP, a much smaller organization than the CP, faced a potentially daunting task. Trying to organize a massive counterdemonstration against the Bund with only three hundred members in a city of nearly seven and a half million residents spread over its famously large geography of five boroughs, would not be easy.59 Nevertheless, the SWP threw itself into the task mobilizing all of its members and resources, including the printing and distributing of two hundred thousand “Stop the Fascists!” flyers all over the city that exclaimed, “Don’t wait for the concentration camps—Act now!”60 One of the potential problems that the SWP ran into was the hostility of many of the organizations within the two million strong Jewish communities of New York City. Those organizations, allied with the Communist Party, the Socialist Party, or LaGuadia were hostile to even protesting the Bund rally and directed their members away from it. The Forward, one of the oldest and most widely read socialist dailies in New York, declared on the day of the Bund rally, “There can be no more shameful thing for the Jews and opponents of the Nazis than such demonstrations which will lead to bloody fights and riots. . .. Avoid the area around Madison Square Garden today and do not participate in any demonstration around the hall.”61 The Communist Party-controlled Yiddish language Freiheit didn’t even mention the protest.62

According to Irving Howe, a young revolutionary socialist at the time and later a much more conservative cultural critic and historian, the “SWP leaflet calling upon people to demonstrate at the Garden was reproduced in the Daily News.”63 Newbold Morris, the acting mayor of New York (LaGuardia was conveniently out of the city), took the airwaves and appealed for people stay away, “The best way to show your support of our democratic institutions and of your concerns for the preservation of our democracy is to shun this assemblage as one would a pestilence.”64 Despite such pleas, the planning for the Bund rally kept it in the news, and worked against the city establishment and its allies. The New York Times reported on the burgeoning police presence that grew from 1,000 to over 1,700 on the night of the rally, including many mounted on horseback.65 Howe remembered that Minneapolis Teamsters leader “Farrell Dobbs, came to New York to instruct us in the arts of street combat (wear a hat and a thick jacket, carry a rolled, heavy newspaper).”66 Protecting themselves from the Bundists, their Christian Front allies, and from the police was a top concern.

New York Police Department (NYPD) officers, overwhelmingly Irish Catholic, were more than sympathetic to Father Coughlin’s Christian Front. Police attacks on anti-Nazi demonstrators were expected.67 “We have enough police here to stop a revolution,” Police Commissioner Lewis J. Valentine boasted to the press, as he surveyed his “blue legions from the Eighth Avenue entrance to the Garden just before the meeting began at 8 o’clock.”68 The NYPD nearly turned Madison Square Garden, according to the New York Times, into “a fortress impregnable to anti-Nazis.”69

The Bund transformed the inside of the Garden to mimic Nazi Party rallies. The walls were festooned with a multitude of American flags, swastika-bearing Bund banners, and a thirty-three-foot high painting of George Washington dominated the stage. All around the Garden balcony were Nazis propaganda banners reading, “Stop Jewish Domination of Christian Americans,” “Wake Up American. Smash Jewish Communism,” “1,000,000 Bund Members by 1940.”70 At 7:50 p.m., a fifty-member drum and bugle corps dressed in Nazi-inspired Order Division (OD) uniforms marched to the stage followed by a color guard of sixty flags, half US and the rest a mix of Nazi and Bund flags. They took their place behind stage and four hundred OD security guards marched down the aisles. All the top leaders of the Bund, led by Fritz Kuhn, took the stage. Speaker after speaker escalated their violent attacks on “International Jewry.” The loudest applause came when Father Coughlin was mentioned. The irrepressible Dorothy Thompson laughed during a speech by Wilhelm Kunze on “Race and Youth,” whereupon a group of OD men grabbed her and had the police remove her from the Garden. Kuhn was the last speaker and he gave the vilest speech,71 but before he finished, Isidore Greenbaum, a Jewish hotel worker who had bought a ticket, couldn’t take it anymore and rushed the stage to attack Kuhn. He was violently tackled by Kuhn’s OD men and beaten badly. He was then turned over to the police who beat him again. The crowd inside the Garden howled for Greenbaum’s and Thompson’s blood.72

Outside the Garden, the SWP was leading the largest anti-Nazi contingent at the corner of Fifty-first Street and Eighth Avenue, face to face with with policemen mounted on horseback. The crowd was peppered with anti-Nazi posters and banners. Howe recalled that Max Shachtman, one of the most prominent SWP leaders, and other party spokesmen were hoisted onto the shoulders of husky party members, and “their piercing voices cracked the air with denunciations of Nazism,” while “a parade of thousands stormed the streets.”73 There were nearly 50,000 surrounding the Garden and another 50,000 onlookers on surrounding blocks. Felix Morrow reporting for Socialist Appeal captured the diverse turnout:

Among those who pressed against the horses, fighting for every inch of ground, were Spanish and Latin American workers, aching to strike the blow at fascism which had failed to strike down Franco; Negroes standing up against the racial myths of the Nazis and their 100% American allies; German American workers seeking to avenge their brothers under the heel of Hitler; Italian anti-fascists singing “Bandera Rossa;” groups of Jewish boys and men, coming together from their neighborhoods, to strike a blow against pogroms everywhere; Irish Republicans conscious of the struggle for the freedom of all peoples if Ireland is to be free; veterans of the World War; office workers, girls and boys, joining the roughly-clad workers in shouting and fighting; workers of very trade and neighborhood of the city.

Some of them brought home-made signs, eloquent of their anxiety to speak out. “Give me a gas mask, I can’t stand the smell of the Nazis,” read one, perched on the end of an umbrella rib. “Hitlerism is Political Gangsterism” read to others, identifying their bearers as “German-Americans of Yorkville.” One group of Jewish-American World War veterans from Brooklyn brought a large American flag.74

Many were shocked by the cops’ aggressive protection of the Nazis. Morrow overheard a young, naïve Jewish kid, stuck behind a police line trying to get to Madison Square Garden, say to his friends, “Help me get up to speak to the police for two minutes, they’ll let us through if we explain that we just want to picket.” Morrow, a few minutes later, saw the kid get trampled “under the horses hooves.”75 Being a veteran didn’t offer protection from the cops, as Morrow discovered when he followed the Brooklyn Jewish War veterans, one of most fearless contingents:

With their big flag at their head, they marched to 53rd Street and 9th Avenue, then down to 9th Avenue to 50th and attempted to turn east toward the Garden. As they marched they sang ‘Hallelujah’ with its original pious words, and shouted to the onlookers: “All those who believe in democracy march behind the American flag.”

As they tried to turn toward the Garden, the police stopped them.

Then the horses drove them on to the sidewalk, then followed them there—eight hundred mounted cops driving them down on the street like so many hunted animals. At 51st Street the cops wheeled and came back at full speed, driving those who had hidden in doorways out into the open where they could ride them down again. Veterans fought back wildly and hard and gave the cops more than they took; at the end of the fight, their flag emerged with only tatters left on the flag-staff. The cops had torn it to ribbons. It was 9:15, two hours after the veterans had appeared. A lesson in democracy.

Despite the brutality of the police, the demonstration was an overwhelming success, beyond the wildest dreams of the organizers. The leaders of the German American Bund and their allies may have thought that their birthday celebration was a great success, but they grossly miscalculated. The Garden event was worldwide news but so was the huge outpouring against them. The Bund’s offensive soon ground to a halt, and they were forced to cancel scheduled rallies in San Francisco and Philadelphia.76 The political establishment began to move against it in their own way by investigating their finances. By the end of 1939, Kuhn was found guilty of embezzlement and on his way to jail.77

- Part 1 of this article appeared in ISR 85.

- “Completing the Program and Putting it to Work” (a discussion between Trotsky and unnamed leaders of the SWP) in Leon Trotsky, The Transitional Program for Socialist Revolution (New York: Pathfinder Press, 1973), 141.

- The founding document “Manifesto and Program of the American League Against War and Fascism” is available online at the Marxists Internet Archive. In a 1991 letter to the New York Times, American League for Peace and Democracy (ALPD) staffer James Lerner reported that among the founding members of the league were Dr. Reinhold Niebuhr of Union Theological Seminary, Rabbi Israel Goldstein of the Social Justice Commission of Rabbinical Assembly of America, representatives of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, the Fellowship of Reconciliation, the War Resisters League, the Women’s Peace Society, the Socialist-led League for Industrial Democracy, organizations of the unemployed and “the Communist Party, whose leader, Earl Browder, addressed that gathering along with the pacifists A. J. Muste and Devere Allen, William Pickens, field secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and the union leader Emil Rieve.” See “Brief History of an Earlier Antiwar Group,” NYT letter, published January 28, 1991.

- E. H. Carr, Twilight of the Comintern 1930–1935 (New York, Pantheon Books, 1982).

- There are many histories of US Communism; one of the best is Fraser M. Ontonelli, The Communist Party of the United States: From the Depression to World War II (New Bruswick, Rutgers University Press, 1991). For a defense of the CP’s policies in that era see Philip Bart, Highlights of a Fighting History: 60 Years of the Communist Party, USA (New York, International Publishers, 1979).

- The Franco-Soviet Mutual Assistance Treaty was signed by the foreign ministers of both countries in May 1935 and went into effect in March of the following year. The French Popular Front government, led by Leon Blum of the Socialist Party, came into office in June 1936.

- Warren Grover, Nazis in Newark (New Brunswick, N.J., Transaction Publishers, 2003), 177.

- Grover, 177.

- Kuhn died an unrepentant Nazi in 1951. See “Fritz Kuhn Death in 1951 Revealed,” New York Times, February 2, 1952.

- Grover, 178.

- Quoted in Ibid., 177.

- Ibid., 175.

- William Mueller, “How Times Men Got on the ‘Inside of the Bund,’” Chicago Daily Times, September 9, 1937. The series ran from September 9, 1937 through September 24, 1937, including John C. Metcalfe’s diary “I Am A US Storm Troop.”

- Mueller, “How Times Men Got on the ‘Inside of the Bund.’”

- “Jersey Veterans Rout Nazi Leader,” New York Times, October 2, 1938.

- I spoke to historian Warren Grover, the leading historian of fascism and antifascism in New Jersey in the 1920s and 1930s, and he has never heard of the Andrew Jackson Democratic Club.

- The “anti-fascism” of the two hundred veterans appears to be largely motivated by xenophobia, at least from the New York Times account of a meeting held immediately after Kuhn was run out of town. “The veterans’ meeting, long delayed, got under way a few minutes later with the crowd so dense in the small room, seating some 200 persons, that speakers addressed others in the street. The veterans granted the floor to Miss Nancy Cox, their organizer, and leader, but when she attempted to put forth a resolution condemning only Nazism, Charles Gilmour, past State Commander of the Veterans of Foreign Wars, took the microphone away from her and accepted a motion to lay the resolution on the table. At the conclusion of the meeting, a resolution was adopted condemning all ‘all isms except Americanism’ and passed without a dissenting vote. The meeting ended with the singing of the national anthem.” See “Jersey Veterans Rout Nazi Leader.”

- “Jersey Veterans Rout Nazi Leader.”

- Ibid.

- “3,000 Storm Nazi Meet; Police Rush to Halt Riot,” Chicago Herald and Examiner, October 17, 1938.

- German American League for Culture Records at http://www.uic.edu/depts/lib/specialcoll....

- “3,000 Storm Nazi Meet; Police Rush to Halt Riot.”

- Ibid. The Lincoln Brigade members were Sam Gibbons, twenty-three, Ernesto Romero, twenty-eight, Maurice Presser, forty-four, and James Robinson, twenty-eight.

- Ibid.

- William L. Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich (New York, Simon and Schuster, 1960), 430.

- Peter Kurth, American Cassandra: The Life of Dorothy Thompson (Boston, Little, Brown & Company, 1991), 282.

- The Stalinists thought it provided them with an opportunity, also. They tried to smear their Trotskyist rivals ludicrously claiming that Grynszpan was a “Trotskyist” in league with the Nazis! See http://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/.... Trotsky believed “Grynszpan is not a political militant but an inexperienced youth, almost a boy, whose only counselor was a feeling of indignation. To tear Grynszpan out of the hands of capitalist justice, which is capable of chopping off his head to further serve capitalist diplomacy, is the elementary, immediate task of the international working class!”

- Grover, 237.

- Grover, 237. Charles Lindbergh, the aviator, was made famous (and rich) by his solo flight across the Atlantic in 1927. He was showered with medals, including the Medal of Honor, and many awards. Lindbergh is a case study in the folly of making a hero out of someone whom you really don’t know anything about. Lindbergh was a racist and a reactionary of the first order, whose views got progressively worse during the Nazi era. Lindbergh was in Germany in mid-October 1938, two weeks after the Nazis required all German Jews to have their passports marked with the letter “J”— for Jude (Jew in German). This didn’t cause Lindbergh any discomfort. He was an official guest of the German government, inspecting the country’s aircraft manufacturing facilities. Hermann Goering, Hitler’s second in command, took the opportunity to award Lindbergh—on behalf of Hitler—the Command Cross of the Order of the German Eagle, the same medal given to Henry Ford in July.

- Grynszpan actually never stood trial. He was later captured during the occupation and most likely died in a Gestapo prison but it is not certain. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herschel_Gr....

- For Thompson’s life as a journalist see Peter Kurth, American Cassandra: The Life of Dorothy Thompson (Boston, Little, Brown & Company, 1991).

- Dorothy Thompson on Herschel Grynszpan in Let the Record Speak (Boston, Houghton & Mifflin, 1939), 256–60. It is a reproduction of the speech she gave on the radio on November 14, 1938.

- Ibid., 260.

- Kurth. 284.

- Richard M. Ketchum, The Borrowed Years 1939–1941 (New York, Anchor Books, 1989), 124.

- Warren, 155–57.

- “WMCA Contradicts Coughlin on Jews,” New York Times, November 21, 1938.

- Quoted in Warren, 160.

- “Four Hurt in Riot as Rivals Raid Silver Shirts,” Chicago Daily Tribune, November 29, 1938.

- William Mueller, “Two Injured, 4 Are Jailed in Anti-Nazi Riot,” Chicago Daily Tribune, November 24, 1938; William Mueller, “Air Silver Shirt Battle in Court,” Daily Times, November 25, 1938.

- Mueller, “Four Hurt in Riot as Rivals Raid Silver Shirts.”

- “Two Injured, 4 Are Jailed in Anti-Nazi Riot.”

- Mueller, “Air Silver Shirt Battle in Court.”

- “Bund Threatens Meet ‘Riot’ Action; 8 Anti-Nazis Go Free,” Daily Times (Chicago), November 27, 1938, “Bund Foes Riot, 1,000 Raid Hall, Battle With Police,” Herald and Examiner, November 26, 1938.

- “Bund Threatens Meet ‘Riot’ Action.”

- Ibid.

- “Anti-Nazis Raid Silvershirts; 4 Hurt in Battle, 9 Arrested,” Daily Times, November 29, 1938.

- “Four Hurt in Riot as Rivals Raid Silver Shirts.”

- “Anti-Nazis Raid Silvershirts.”

- Among the anti-Nazis arrested that night were Milton Marks, twenty-one years old, of 2751 North Whipple; Dave Forman, twenty-one, of 2525 Division Street; Max Kamm, twenty-one, of 2416 Cortez Street, Herman Lieb, nineteen, of 1544 Millard Avenue; Irv Botnek, twenty, of 1505 South Ridgeway Avenue, Seymour Brodfsky, seventeen, of 2905; Aaron Ragins of 3101 Augusta Boulevard, and Julius Rosenthal, twenty-two, a photographer for the Daily Record, both of 1838 North Halsted Street. All are young men, most with identifiably Jewish last names. The Daily Record might be a reference to the Midwest Daily Record, a newspaper of the Communist Party.

- “Four Hurt in Riot as Rivals Raid Silver Shirts.”

- Madison Square Garden (1925), Wikipedia, available at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Madison_Squ....

- Photos of a Bund meeting, complete with image of George Washington next to a swastika, from Life magazine’s March 7, 1938 issue, http://books.google.com/books?id=vkoEAAA....

- Sander Diamond, The Nazi Movement in the United States: 1924-1941 (Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 1974), 324.

- Ibid., 325.

- Ibid., 324.

- For a short biography of Jerome see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/V._J._Jerome.

- Large sections of Jerome’s March 8, 1939 interview in the Daily Worker were quoted in “The Best Way to Fight Against Fascism is to Lie Down and Make Believe You are Dead,” by Felix Morrow, Socialist Appeal, March 10, 1939.

- I estimated the membership of the SWP based on the number of members they reported for NYC at their founding convention in 1938, see Founding of the Socialist Workers Party: Minutes and Resolutions 1938-39 (New York, Monad Press, 1982), 85-86.

- The number of flyers that the SWP distributed was reported in the NYT, see “Bund Rally To Get Huge Police Guard,” New York Times, February 19, 1939. “Stop the Fascists!” is in the possession of the author.

- Quotes from the Forward and lack of quotes from the Freihiet are in “The Craven Jewish Press,” Socialist Appeal, February 24, 1939

- Ibid.

- Irving Howe, A Margin of Hope (New York, Mariner Books, 1984), 41.

- “Bund Rallies Amid Tumult At The Garden,” New York Herald Tribune, February 21, 1939.

- “Bund Rally To Get Huge Police Guard,” New York Times, February 19, 1939.

- Irving Howe, A Margin of Hope (New York, Mariner Books, 1984), 41.

- On the relationship between the NYPD and the Christian Front see “LaGuardia’s Police,” Nation, July 22, 1939.

- “22,000 Nazis Hold Rally in Garden; Police Check Foes,” New York Times, February 21, 1939.

- Ibid.

- “Bund Rallies Amid Tumult at The Garden,” New York Herald Tribune, February 21, 1939.

- Kuhn’s speech can be heard at http://www.albany.edu/talkinghistory/arc...

- “Bund Rallies Amid Tumult at The Garden,” and “22,000 Nazis Hold Rally In Garden; Police Check Foes,” New York Times, February 21, 1939.

- Irving Howe, A Margin of Hope (New York, Mariner Books, 1984), 42.

- Felix Morrow, “All Races, Creeds Join Picket Line,” Socialist Appeal, February 28, 1939.

- Ibid.

- The SWP followed up their success in New York by leading five thousand anti-Nazi demonstrators against the Bund in Los Angeles, “Fight Nazis in Los Angeles,” Socialist Appeal, February 28, 1939.

- “Kuhn Found Guilty On All Five Counts; He Faces 30 Years; Leader of the Bund Here Will Be Sentenced,” New York Times, November 30, 1939.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Google+

Google+ Tumblr

Tumblr Digg

Digg Reddit

Reddit StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon