The state of US politics after the 2012 election

The results of the 2012 national election revealed a much more liberal and diverse US electorate than the US political establishment recognizes. Despite this, the US ruling class’s single-minded commitment to austerity remains unchanged. The future of US politics will depend on how “our side,” broadly defined, confronts the challenge of austerity in the next period.

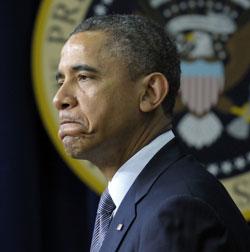

The victory of President Obama and the Democrats in 2012 was unambiguous and decisive. Obama beat Republican challenger Romney by more than 4.5 million votes nationwide, while Democrats tallied more votes than Republicans in both the Senate and House races. Romney ended up with about 47 percent of the national vote—an ironic result, given his earlier disparagement of the “47 percent” living on government handouts. This produced a net gain of two Senate seats and eight House seats for Democrats. Although Democrats won more than 1 million votes in House races nationwide, GOP-led gerrymandering allowed Republicans to hold onto the House.

More importantly, the election revealed a liberal trend among the electorate that was younger, more female and more non-white than most mainstream commentators predicted. Referenda results showed victories for marriage equality, immigration rights, abortion rights, union political rights and marijuana legalization. Exit polls showed the electorate overwhelmingly supporting Obama’s repeated calls for increased taxes on the rich. Indeed, it largely opposed Romney because it associated him with supporting policies favoring the rich. Even though the groups that were decisive in reelecting Obama were those most likely to have suffered in the Great Recession and its subsequent weak recovery, they stuck with Obama because they concluded that Romney and the GOP would only have made things worse.

At the same time, the election results left the national GOP in a shambles, as leading Republicans from the Romney campaign to pundits, indicated shock and surprise. Whether the Romney camp was truly as clueless as its postelection apologies suggested is debatable. But the fact remains that “Team Red” outspent “Team Blue” ($1.23 billion to $1.1 billion) and, despite economic malaise and a widespread sense of disappointment in Obama, still lost handily. GOP apparatchiks attributed Romney’s loss to a list of technical and tactical failures, eliding the core reason: its agenda is unpopular. As National Review writer Ramesh Ponnoru, put it, in one of the more honest conservative election postmortems:

The perception that the Republican party serves the interests only of the rich underlies all the demographic weaknesses that get discussed in narrower terms. Hispanics do not vote for the Democrats solely because of immigration. Many of them are poor and lack health insurance, and they hear nothing from the Republicans but a lot from the Democrats about bettering their situation. Young people, too, are economically insecure, especially these days. If Republicans found a way to apply conservative principles in ways that offered tangible benefits to most voters and then talked about this agenda in those terms, they would improve their standing among all of these groups while also increasing their appeal to white working-class voters. For that matter, higher-income voters would prefer candidates who seem practical and solution-oriented. Better “communications skills,” that perennial item on the wish list of losing parties, will achieve little if the party does not have an appealing agenda to communicate.

Despair has led many Republicans to question their earlier confidence that America is a “center-right country.” It is certainly a country that has strong conservative impulses: skepticism of government, respect for religion, concern for the family. What the country does not have is a center-right party that explains how to act on these impulses to improve the national condition. Until it does, it won’t have a center-right political majority either.1

Liberal economist Paul Krugman went further, declaring, “So Republicans have suffered more than an election defeat, they’ve seen the collapse of a decades-long project” of trying to repeal the New Deal and Great Society.2

Even if the GOP’s generations-long political project has run its course, that does not mean it is planning to reevaluate or to change course in any meaningful way. The Michigan GOP’s forcing through “right to work” legislation on a day’s notice in December should end that speculation. In positioning themselves for presidential runs in 2016, figures like Rep. Paul Ryan (R-WI) and Sen. Marco Rubio (R-FL) have retooled GOP rhetoric without changing any of the hard-right substance with which they are identified. George W. Bush’s and Karl Rove’s “compassionate conservatism,” the last attempt to repackage conservatism for a broader audience, fit with a period (the early 2000s) of relative economic boom. In an epoch of austerity, the most zealous advocates for slashing and burning the welfare state will want to maintain a hard-right GOP as one of their political instruments.

Judging from exit and opinion polls, President Obama and the Democrats emerged with a popular “mandate” centered on several main planks: focus on jobs and the economy, rather than the deficit; increase taxes on the rich; and protect “entitlements” (i.e. Social Security, Medicare or Medicaid).3 In the subsequent White House-GOP negotiations on the largely contrived “fiscal cliff,” the White House appeared wedded (we think!) only to the tax-raising plank of that program. It showed itself more than willing to seek a deal that would cut entitlements in some way as the tradeoff of tax increases. Cuts in entitlements have become the conventional Washington wisdom as a means to resolve Washington’s budget woes. Moreover, the White House allowed the payroll tax holiday—the highly stimulative tax cut targeted to working people—to expire, raising the taxes of a median-salary worker by $1,000 or more.

Obama has solicited help from leading CEOs, such as Honeywell’s David Cote and GE’s Jeffrey Immelt, to press the GOP to accept higher income taxes. Cote and Immelt are among the CEOs who bankrolled the corporate “Fix the Debt” campaign that declares,

Any realistic solution to our budget problems must cut out wasteful and low priority spending, must slow the growth of unsustainable entitlement costs, and must simplify the tax code and eliminate loopholes through pro-growth and revenue-positive tax reform. The recommendations of the Simpson-Bowles National Commission On Fiscal Responsibility and Reform and other recent bipartisan efforts can serve as an effective framework for a plan to reduce the federal debt by more than $4 trillion over ten years.4

Official Washington concedes that Obama had the “leverage” to win increased taxes on the rich, as he obtained with the January 1 deal to postpone the “fiscal cliff”. But Obama is seeking to rationalize entitlements and even to rewrite the corporate tax code. The White House may sell this rotten compromise as the price that had to be paid to avoid a Republican attempt to hold the economy hostage in 2013. But it’s clear that Obama has long sought a “grand bargain” along the lines of the 2010 Simpson-Bowles commission proposal. Whatever the outcome of the battles with Congress over a series of contrived budget crises, it’s clear that the White House and congressional Democrats have “locked in” austerity measures for at least the next decade. This was the outcome of the Congress-White House deal over the debt ceiling in 2011, which established annual “caps” on domestic non-defense discretionary spending. A deal with the GOP in early 2013 will only reinforce the path of austerity.

The condition of the US economy over the next period will also shape the contours of US politics. In October, International Monetary Fund (IMF) analysts predicted a 1 in 6 chance of the global economy growing at a rate of less than 2 percent, “which would be consistent with recession in advanced economies and low growth in emerging market and developing economies.” Without acknowledging its own role in enforcing an austerity regime on the Euro zone, it labeled the Euro crisis the “most obvious threat to the global outlook.” At the same time, it warned the US government that a failure to address the “fiscal cliff” and to raise the federal debt ceiling could cause the US to “fall back into a recession.”5 Even the IMF’s rather guarded prediction puts the chance of recession at 1 in 6. Most mainstream economists predict the US will continue its slow recovery from the depths of the recession, with a possibility that the US economy will accelerate in the second half to 2013 and into 2014.6 The depression in the housing and construction industry bottomed in 2012, and state and local government cuts also appear to have stopped. As a result, two major factors that have contributed to economic decline over the last six years may have finally reversed their slide, and may now add to economic growth.7

But even if the economy continues its slow recovery, unemployment declines, and public opinion credits Obama and the Democrats with ending the “Great Recession,” the resulting economy will leave the US working class worse off than its forebears of only a generation ago. Unemployment will likely remain above 7 percent, and record numbers of American workers will have remained out of work for years. Median US family incomes, after almost four years of economic recovery, stand at 1996 levels.8 The widely touted manufacturing renaissance under Obama has returned only about one-tenth of the 5 million manufacturing jobs lost in the first decade of the 2000s, and it is based on the reduction of US unit production costs by 11 percent between 2002 and 2010.9 The US is well on its way to becoming the low-wage neoliberal economy that Corporate America has desired for decades.

Although the electorate emphatically rejected the plutocratic austerity-driven politics of Romney, Obama looks set to deliver them austerity nonetheless. The wide gap between popular aspirations, electoral “voice” and actual government results underscores what might be called a “crisis of representation.” Public opinion lies far to the left of the political establishment, and distrust of big business and politicians is high, but the organizations that are supposed to represent working people are weak or captive to the Democratic Party. In the wake of the success of antilabor attacks in Michigan and Wisconsin, organized labor is approaching a tipping point beyond which it will cease to have a meaningful role in the national political economy.

Since at least early 2011, “our side” of the class divide has demonstrated its desire to challenge the dominant politics of austerity. From the Wisconsin uprising, through Occupy, through the fall 2012 Chicago teachers’ strike, it’s clear that large numbers of workers and young people (and young workers) are fed up with an economy and government that delivers the majority of its benefits to the corporations and richest 1 percent. Yet, with the important exception of the Chicago teachers’ strike, all of these movements against austerity did not succeed in pushing back the austerity drive. Wisconsin’s promise was squandered through electoralism. The government pushed Occupy off the streets while liberals co-opted its atmospherics (rather than its substance) for the 2012 election. Organized labor’s pathetic response to the existential attack in Michigan—essentially conceding the fight in 2012 while promising to wage an electoral campaign in 2014— underscored how singular the Chicago teachers’ victory was. Michigan illustrated that the main leadership of US labor has no strategy to defend its members outside of Democratic Party electoralism. It is merely committed to managing the decline of its organizations. But in retreating to avoid a complete rout, it is actually bringing itself closer to the “union-free” environment that labor haters want.

The struggles against oppression and exploitation of the last two years are important, even if they have not attained the scale that they would need to really shift the austerity drive. Struggles like those listed above, and others (e.g., the campaigns against Wal-Mart, local struggles against racism and police violence, environmental struggles around climate change) have helped a new generation of fighters to identify and solidarize with each other. They are laying the groundwork for future (hopefully) larger struggles to come. And they are occasioning debates among activists about what is really necessary to change society.

For the younger, more radical activists, the election period had a dampening impact on struggle, even for those who lived in the “non-swing-state” areas of the country that the election bypassed. With the election over, its dampening impact has also been lifted. The Left can, and should, take the lead in pushing for activism. Obama and the Democrats made (or implied) a number of promises to the “emerging electorate,” for example, promises on immigration reform and marriage equality. Take the example of immigration reform. We know from experience that if the White House advances an immigration reform bill, it’s likely to follow the outlines of the Schumer-Graham bill that emphasizes “enforcement” and falls far short of the demands of immigrant rights activists. For many “DREAMers,” whose activism helped put immigration reform back on the White House agenda, this sort of a compromise will amount to a sellout. Many people will be open to an argument about the need for more action from below, as well as for the need to build a political alternative to two parties of big business.

The final point—about the possibility of the emergence of a political alternative—will bear watching over the next period. In 2012, support for third party alternatives to the left of the Democrats was low. But if the experience of the last neoliberal two-term Democratic administration provides guidance, the emergence of a substantial third party or electoral alternative can’t be ruled out. The 2000 Nader Green Party campaign provided a political vehicle for a layer of activists, fed up with eight years of Clintonism, to break to the Democratic Party’s left. While our emphasis will continue to be on building organizations that can mount a struggle against Washington’s austerity agenda, the struggles themselves will have a political echo that socialists should encourage.

- Ramesh Ponnoru, “The Party’s Problem,” National Review Online, November 14, 2012, http://www.nationalreview.com/articles/3....

- Paul Krugman, “The GOP’s Existential Crisis,” New York Times, December 13, 2012.

- Christian E. Weller, “Continuing Our Resilient Economic Recovery,” December 11, 2012, Center for American Progress Action Fund, cites a number of surveys emphasizing these points.

- The “Fix the Debt” campaign has enlisted hundreds of leading CEOs to press members of Congress to support the plan of “Fix the Debt’s” founders, former Sen. Alan Simpson and former White House chief of staff Erskine Bowles. Its co-chairs are former GOP Sen. Judd Gregg and former DNC chair and Pennsylvania Gov. Ed Rendell. In other words, it is a thoroughly bipartisan operation.

- Quotes from International Monetary Fund, “Executive Summary,” World Economic Outlook 2013 (October 2012). Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund, 2012, xvii – xix.

- See “NABE Outlook December 2012: NABE Panel Expects Modest But Accelerating Growth in 2013,” National Association of Business Economists, December 2012 at http://nabe.com/outlook/Dec_2012_NABE_Ou....

- One well-known early critic of the housing bubble, Bill McBride of www.calculatedrisk.org, cited the bottoming housing market and local government job cuts as reasons to be optimistic about the future US economy, in Joe Weisenthal, “The Genius Who Invented Economics Blogging Reveals How He Got Everything Right And What’s Coming Next,” Business Insider, November 21, 2012, at http://www.businessinsider.com/bill-mcbr....

- See US Census Bureau, Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2011 (Washington, DC: Census Bureau, 2012), 5.

- Gene Sperling, “Remarks at the Conference on the Renaissance of American Manufacturing,” March 27, 2012, available at http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/....

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Google+

Google+ Tumblr

Tumblr Digg

Digg Reddit

Reddit StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon