The Communist Party and Black Liberation in the 1930s

A commonly-held view on the left is that Marxism has always fallen short when it comes to fighting racism. As a politics of working-class struggle, it “privileges” class over race, arguing that race is unimportant, or at best, a secondary issue.

One author, a “neo-Marxist,” writes a typical attack on Marxism in the journal Rethinking Marxism:

Marx was always concerned primarily with capitalism as a mode of production, and with emancipating Europe’s predominantly white workers…Orthodox Marxists, in America and elsewhere, have, like Marx, always reduced concrete experiences of racial bigotry directly to capitalism…When capitalist economic exploitation died, so would bigotry. Blacks, therefore, needed to mute or disregard entirely racial issues, and emphasize instead interracial working-class solidarity. They had to mobilize for socialism rather than against racism. 1

The author then attacks the U.S. Communist Party (CP) because of its “reduction of black consciousness to objective economic categories.” Though he acknowledges that the CP in the 1930s made “valiant attempts to organize workers and fight discrimination” which, “on occasion, improved the conditions for thousands of black families,” white CP leaders manipulated and “established theoretical dominance over blacks.”

There are two problems with the argument. It sets up a caricature Marxism that never existed, and it presents Stalinism as genuine Marxism.

Fighting oppression has always been central to Marxist theory and practice. Marxists have never counterposed working-class unity to fighting against racism. On the contrary, the fight against all forms of oppression is an indispensible condition for that unity.

Moreover, the attack on the CP in the 1930s is misplaced. If anything, the CP’s work against racism in the 1930s confirms both the necessity and the practical possibility of uniting Black and white workers, not only around common economic struggles, but also over issues of Black oppression. That the CP ultimately compromised its commitment to fighting racism reflects not the fact that “orthodoxy” has historically sold out the Black struggle, but that the CP in the 1930s had become a thoroughly Stalinist party.

This article aims to argue these points by focusing on five areas of the CP’s work: its theoretical development of the Black question in the 1920s; its role in organizing a multiracial fight for unemployment relief; its national campaign around the Scottsboro case; its work in Alabama organizing Black workers; and its role in building a multiracial labor movement in the CIO.

Marxism, the CP and the Black Question

Marx’s and Engel’s writings still provide a brilliant starting point for understanding the role of racial and national oppression. They supported every real movement against oppression. Expressing his support for the North in the Civil War, Marx wrote in Capital:

In the United States of America, every independent movement of the workers was paralyzed as long as slavery disfigured a part of the Republic. Labor cannot emancipate itself in the white skin where in the Black it is branded.2

Marx also supported the Irish independence movement and argued that British domination of Ireland helped to hold back the struggle of English workers:

All English industrial and commercial centers now possess a working class split into two hostile camps: English proletarians and Irish proletarians. The ordinary English worker hates the Irish worker because he sees in him a competitor who lowers his standard of life. Compared with the Irish worker he feels himself a member of the ruling nation and for this very reason he makes himself into a tool of the aristocrats and capitalists against Ireland and thus strengthens their domination over himself…The Irishman pays him back with interest in his own money. He sees in the English worker both the accomplice and the stupid tool of English rule in Ireland.

This antagonism is artificially sustained and intensified by the press, the pulpit, the comic papers, in short, by all the means at the disposal of the ruling classes. This antagonism is the secret of the impotence of the English working class, despite its organization. It is the secret which enables the capitalist class to maintain its power, as this class is perfectly aware.3

Lenin brought Marx up to date for the period of imperialism, when the carve-up of the globe between the world’s biggest powers was awakening movements against national oppression.

The proletariat must struggle against the enforced retention of oppressed nations within the bounds of the given state…The proletariat must demand freedom of political separation for the colonies and nations oppressed by “their own” nation. Otherwise, the internationalism of the proletariat would be nothing but empty words; neither confidence nor class solidarity would be possible between the workers of the oppressed and the oppressor nations…

On the other hand, the socialists of the oppressed nation must, in particular, defend and implement the full and unconditional unity, including organizational unity, of the workers of the oppressed nation and those of the oppressor nation. Without this it is impossible to defend the independent policy of the proletariat and their class solidarity with the proletariat of other countries.4

When the Communist International was formed in 1919—of revolutionary parties which had split from the reformist Second International—Lenin’s ideas were the starting point for its policies.

Lenin and the Comintern leaders pushed the U.S. Communists to take a more revolutionary approach to the Black question. Under their influence, the Communist Party broke with the Socialist Party’s policy in the U.S. that saw racism simply as an extension of class oppression. Initially the CP suffered from the same theoretical limitations. The founding CP convention in 1919 referred to the Black question as “a political and economic problem. The racial oppression of the Negro is simply the expression of his economic bondage and oppression, each intensifying the other.”5

The impact of the Comintern and Lenin’s theory can be seen in the program of the Workers (Communist) Party in 1921 which recognized the special character of Black oppression:

The Negro workers in American are exploited and oppressed more ruthlessly than any other group. The history of the Southern Negro is the history of a reign of terror—of persecution, rape and murder…Because of the anti-Negro policies of organized labor, the Negro has despaired of aid from this source, and he has either been driven into the camp of labor’s enemies, or has been compelled to develop purely racial organizations which seek purely racial aims. The Workers Party will support the Negroes in their struggle for Liberation, and will help them in their fight for economic, political and social equality…Its task will be to destroy altogether the barrier of race prejudice that has been used to keep apart the Black and white workers, and bind them into a solid union of revolutionary forces for the overthrow of our common enemy.6

The CP was the first U.S. socialist organization to recognize that the specially-oppressed condition of Blacks required that socialists champion the fight against their legal, political, economic and social oppression. James Cannon, the first national chairman of the Workers Party (as the CP was called) who later founded the Trotskyist opposition to Stalinism in the U.S., argued that the intervention of the Communist International was decisive in shifting the CP on this question. This new approach made the CP attractive to a layer of Blacks radicalized by the War, the Russian Revolution and the upswing in class struggle in the U.S. in that period.

Several key leaders from a secret society called the African Blood Brotherhood were drawn into the CP. The Brotherhood was nationalist—calling for a separate state for Blacks in the U.S. But it was also inspired by the Russian Revolution and gravitated toward socialist politics. The Brotherhood advocated complete social, economic and political liberation, and unity between Blacks and “class-conscious revolutionary white workers.”7 A majority of the leadership of the Brotherhood—including Cyril Briggs, Richard B. Moore and Harry Haywood—joined the CP and formed the first Black cadre within it.

Though the CP’s recruitment of Blacks in its first several years was not high, it laid the foundation in this period for its successes in the 1930s.

The Impact of Stalinism

Sadly, by the onset of the Depression the CP had ceased to be a genuine revolutionary workers party. Comintern intervention had initially helped the fledgling CP. But as the Russian Revolution degenerated, so too did the Comintern. As brutal civil war caused Russian industry and agriculture to collapse and cities to be depopulated, Stalin’s bureaucratic rule from above replaced the democracy of the soviets (workers’ councils) from below. The Stalinist bureaucracy used the enormous prestige of the Revolution to transform the Comintern from an organization dedicated to world revolution into an organization subordinated to the foreign policy interests of the USSR.

The year 1928 marked the final consolidation of a new state capitalist ruling class in Russia. In Stalin’s first Five-Year Plan, millions of workers were sent into labor camps and millions of peasants driven onto collective farms, as the state forced the pace of industrial development. This turn to bureaucratic state capitalism, which represented the final liquidation of the Bolshevik Revolution, was portrayed as a “left” turn.

This turn was mirrored in the Comintern:

In 1928 the Comintern, now completely under Stalin’s control, promulgated the ultra-left dogma of the ‘Third Period’ and ‘Social Fascism,’ policies which it was to follow until Hitler came to power. According to this ‘theory’…the Third Period, now opening, was to bring the death agony of capitalism. 8

Communist Parties were now ordered to reject any united front with Social Democrats, who were denounced as “social fascists.” CPs were ordered to form separate, dual “red” unions controlled by the CPs. The main enemy was not fascism—which sought to annihilate the working-class movement—but the “social-fascist” reformists and trade union leaders.

The result of this seemingly super-left-wing “theory” was furious activity in isolation from the mass of workers still influenced by the reformist organizations—and practical passivity toward the building of united struggles with nonrevolutionary workers. This policy did not at all represent a genuine commitment to revolution. Quite the contrary. Stalin wanted to prevent social upheavals that might provoke intervention against Russia from foreign powers. A policy which prevented an aggressive united front against Hitler fit well into this strategy.

In Germany, the Third Period line proved disastrous. The refusal of the CP to unite with the mass Social Democratic party against Hitler opened the way to Hitler’s victory and the worst defeat of the working class in history.

In the U.S., the Third Period’s impact was not as disastrous because the stakes were not as high. Nevertheless, the Third Period policy of denouncing all political forces to the right of the CP as fascist or “social-fascist”—from Roosevelt to the American Federation of Labor to the Socialist Party—cut the CP off from thousands of potential recruits and allies in the struggle.

Over time, the CPs zig-zagging policies in response to the demands of USSR foreign policy weakened its appeal and demoralized many militants it had attracted to its ranks. But the USSR was seen in the 1930s by millions of workers all over the world as a socialist society. In spite of its Stalinist degeneration, the enormous prestige of the Russian Revolution attracted to the CP the best militant working-class fighters. As the struggle picked up in the mid-1930s, the CP became the main vehicle of radicalization among workers. Thousands of workers joined or were influenced by the Communist Party. In 1930, it had 7,545 members. That number tripled to 23,760 in 1934 and tripled again to 75,000 in early 1938.9

Black Belt Theory

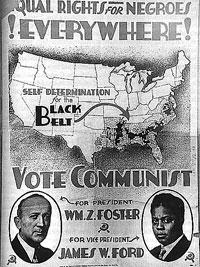

In 1928, the Comintern declared that Blacks in the U.S. constituted a nation, and they called for “self-determination in the Black Belt.” (The Black Belt was a swath of territory cutting through the South known for its rich, dark soil, in which rural Blacks at that time were concentrated in large numbers).

The theory did not fit at all with the conditions and aspirations of Blacks. Thousands were moving to the North to get factory jobs, as the sharecropping system was dying out and Blacks were being forced off the land. There was simply no basis—in conditions or in the aspirations of Blacks themselves—for demanding a separate state in the Black Belt. That does not mean there wasn’t nationalist sentiment. Particularly in the North, Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), which called for a return to Africa, attracted a mass following. But Garvey’s appeal was not because Blacks really wanted to return to Africa, but because of his message of racial pride.

Moreover, the call for a separate state in a society of enforced segregation could be interpreted as supporting segregation, not fighting it. Perhaps this explains why in practice the slogan was never pushed in the North, and was quickly and quietly dropped in the South. What was left was an overriding commitment by the CP to “consider the struggle on behalf of the Negro masses…as one of its major tasks…[T]he Negro problem must be part and parcel of each and every campaign conducted by the party.”10

The Setting

The 1930s were a period of economic crisis and mass working-class radicalization. Official unemployment went from 8.8 percent in 1930 to a peak of 25.2 percent in 1933 (over 15 million workers!), never dipping below 13.8 percent throughout the pre-war period.11

For Blacks, the numbers were even more startling. In cities like Detroit, Chicago, Philadelphia and New York, Black unemployment in 1932 ranged from 40 to over 55 percent. Wages were low, and relief was practically nonexistent.12

Roosevelt’s National Recovery Act of 1933—a program of government spending aimed at alleviating the impact of the crisis—actually worsened conditions for Blacks. Writes historian Philip Foner,

Thousands were fired and replaced by white workers on jobs where blacks were being paid less than established minimum-wage scales; by August, 1933, blacks were calling it the ‘Negro Removal Act’…Legal sanction was given to lower wage scales in Southern industry, especially for blacks.13

The Depression created the conditions for a mass explosion of discontent among all workers, but particularly among Blacks. But the craft-dominated and segregated American Federation of Labor (AFL), as well as traditional Black organizations like the Urban League and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), with their emphasis on legal action, offered little or no response to the crisis. The fact that the CP made it a priority to raise demands around racism as part of the general class struggle meant that Black workers were more receptive to the CP’s class appeal for united struggles of Black and white workers.

The CP initiated a multitude of struggles against racism through the Depression decade. CP members led struggles against poor housing and evictions, for unemployment relief, against police terror and lynching. They organized mass campaigns for the defense of victims of racist injustice; they petitioned against segregation in baseball; they organized interracial meetings and dances, demonstrations and social gatherings both in the North and in the South; they initiated campaigns to root out manifestations of racism inside the party. When Communists traveled to Washington to demonstrate on behalf of the Scottsboro Boys, they stopped off on the way to sit down in restaurants that refused to serve Blacks—a tactic adopted by the civil rights movement in the 1960s.14 In these years, the CP was able to challenge traditional Black organizations like the NAACP and the Garveyites.

As a result, the CP’s Black membership grew from 200 members in 1930 (less than 3 percent of the total) to 7,000 in 1938 (over 9 percent). In some cities, the percentage of Black members was considerably higher. In Chicago in 1931, close to one-quarter of the city’s 2,000 members were Black. As Blacks constituted 11 percent of the total U.S. population at the time, these figures represent a small but important step in building a multiracial movement. At a time when segregation was rampant—legally in the South, defacto in the North—the CP was virtually the only integrated organization in the country.15

The Party systematically developed and promoted Black leaders in the organization, starting in 1929 by electing six African Americans to its central committee. It also slated Black CP leader James Ford as its vice-presidential candidate in the 1932 and 1936 elections.

The Early Years of the Depression

In 1930 the Communist Party called for an International Unemployment Day on March 6—a series of national protests to demand unemployment relief. Marches across the country brought somewhere between 500,000 to a million people out. This was the first great upsurge of the Depression, and the first time in many cities that Black and white unemployed were seen marching side by side for their rights.

In New York’s Union Square, the protest brought out over 50,000 people, a quarter of whom were Black. Four cops and more than 100 demonstrators were injured when 1000 cops stormed into the crowd swinging nightsticks. Blacks fought side by side with whites to protect the march against the police.

Thousands of people joined in CP-led multiracial demonstrations to save families from evictions across the country. In one incident in Chicago on August 3, 1931, three Blacks were killed when police opened fire on 500 people who had just prevented an eviction of a Black woman.

All week long, mass protest meetings of 5,000-8,000 people were held and 1,500 police patrolled the South Side with riot guns and tear-gas bombs. The bodies of Abe Gray, a Communist, and Jim O’Neil, a member of an Unemployed Council, lay in state underneath a large portrait of Lenin. A funeral procession for the fallen workers drew 60,000 participants and 50,000 onlookers, blocking all traffic.16

The Ford Hunger March shows how the CP made the demands of Black workers a critical component of its unemployment work. On March 7, 1932, the CP organized a hunger march on Ford Motor Company demanding jobs, 50 percent pay for unemployed and $50 winter relief per family. Workers carried signs saying “No discrimination against Negroes as to jobs, relief, medical services, etc.” Police opened fire on the 3,000 demonstrators. Four were killed and more than 30 wounded. One of the four workers killed in the attack was Curtis Williams, an unemployed Black Ford worker. Five days later, a funeral procession held for the four slain workers drew 30,000 workers—the largest demonstration in Detroit up to that time.17

In Harlem, the CPs unemployed work earned it a reputation as the organization willing to fight for Black and white unemployed workers. In 1932, Black CP organizers led several local marches for relief from local authorities. In one of Harlem’s “local Scottsboros,” the CP organized protests to free Sam Brown, an unemployed council organizer who was sentenced to six months in jail for leading an unemployed protest (the white council leader arrested with him received only a 10-day sentence). A rally of hundreds in which whites predominated was organized in front of the judge’s house. After a fight with police, many were arrested. Historian of the Harlem CP Mark Naisan writes,

The willingness of so many white communists to endure arrests and beatings to protect a black comrade gave Communist arguments in behalf of interracial solidarity a new logic and concreteness. Several of the black council leaders who participated in this struggle… developed into some of the most solid and reliable Harlem Communists.18

These struggles achieved results. For example, a demonstration of 500 led by the Harlem unemployed council in 1933 won rent and food checks for 25 people. The CP gained a reputation as the organization for Black working-class men and women to turn to.

In the fight for jobs, the CP faced fierce political competition from Black nationalist groups. One prominent local nationalist, Sufi Abdul Hamid—who soon after began calling himself the “Black Hitler” and demanding that Jews be driven out of Harlem—organized a boycott of Woolworth and other stores in 1934 on an anti-white basis, collecting money from his supporters in return for promising them jobs in the stores they picketed.

Arguing that this approach would deepen racial divisions between Black and white workers, the CP organized its own jobs campaign, uniting Blacks and whites on pickets calling for hiring Blacks but demanding that no whites be fired. The CP-led boycott of the Empire Cafeteria on 125th Street forced the restaurant to hire four Blacks without firing any white employees. The impact of these struggles, in which white workers were seen taking the lead in the fight for jobs for African Americans, enhanced the CP’s prestige.

However, Third-Period sectarianism toward other political forces weakened the impact of their work. In 1930, for example, Communists disrupted a Harlem conference on unemployment chaired by A. Philip Randolph (Black president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and leader in the Socialist Party). Though the conference demands included a call for a five-day work week, the eight-hour day and public works for the unemployed, Communists who attended denounced the participants as “traitors.”19

The CP’s ultraleftism cut it off from potential recruits and allies. But its militancy tapped into a growing anger and bitterness that other organizations at first would not touch—and its championing the needs and rights of Black workers earned it a reputation as antiracist that attracted significant numbers of Blacks into its ranks.

Scottsboro

The campaign to free the Scottsboro boys, more than any single event, marked the Communist Party’s emergence as a force in Harlem life. The Party’s role in the case, and its conflicts with the NAACP, were front-page news for years, and its protest rallies gave it entry to churches, fraternal organizations, and political clubs that were previously closed to it. From soapboxes, pulpits, and podiums, Black and white communists made the details of the Scottsboro case a part of the daily consciousness of the community until ‘Scottsboro became synonymous with southern racism, repression and injustice.’20

In 1930, nine poor Black men and boys, aged 13-21, were arrested in Alabama and charged with raping two white women on a freight train. Though there was no evidence implicating them—even evidence that rape had taken place—the nine were tried, convicted and sentenced to death within two weeks amid a lynch-mob atmosphere.

The CP-led International Labor Defense (ILD) quickly moved on the case, winning the defendants and their parents over to a campaign involving both a strong legal defense—which for the first time challenged the exclusion of Blacks from juries—and a mass protest movement to secure their release.

The Scottsboro case divided the Black population along class lines. The NAACP—committed to a policy of gentle pressure through the courts and Congress and opposed to mass protest— initially remained aloof toward the case. “The last thing the NAACP wanted,” writes Scottsboro historian Dan T. Carter, “was to identify the Association with a gang of mass rapists unless they were reasonably certain the boys were innocent or that their constitutional rights had been abridged.”21

Alarmed that the Communist Party might upstage them, the NAACP quickly maneuvered, without success, to take over the Scottsboro case. But even then, they did so not with the intention of proving the defendants innocent, but to secure them a “fair trial.” A “fair trial” from an all-white jury in 1930s-Alabama for nine Black men and boys accused of raping two white women was impossible.

The NAACP went out of its way to distance itself from the CP, offering its more moderate approach as a way of forestalling radicalism among poor Blacks. NAACP leader Charles McPherson, for example, discouraged an ILD-led mass campaign to defend another Black victim of Southern injustice because it “will make the white people in Birmingham mad.”22

The CP was so sectarian that when lawyer Clarence Darrow—the most famous liberal lawyer in the U.S.—offered to help defend the Scottsboro Boys in 1931, the ILD attorneys would only accept his help on the condition that he renounce the NAACP.

The ILD held meetings with Scottsboro mothers across the country, sometimes numbering in the thousands. One of the mothers, Janie Patterson, who referred to herself as “one of the reds,” became an effective speaker in the campaign. At a rally in New Haven, Connecticut, she said, “They tried to tell me that the ILD was low-down whites and reds. I haven’t got no schooling, but I have five senses and I know that Negroes can’t win by themselves…I don’t care whether they are Reds, Greens or Blues. They are the only ones who put up a fight to save these boys and I am with them to the end.” 23

The CP organized a mass protest in Harlem in April 1931 that started with 200 mostly-white Communists and swelled to over 3,000, mostly Blacks, protesting the legal lynching.

The ILD also defended workers against lynching, and fought to free other victims of racist injustice. To give just one example: A Selma Black city worker, Ed Johnson, was arrested and charged with rape in 1934. Soon after, the white woman admitted that the police had forced her to lie. When police tried to hand Johnson over to a lynch mob, the ILD organized a defense squad of ex-service men and escorted Johnson safely away.24 Historian of the CP in Birmingham, Robin Kelley, brilliantly sums up the role of the ILD:

Black and white activists in the ILD asserted themselves as defenders of the African-American community’s basic constitutional and civil rights, and thus entered a realm of political practice usually considered the preserve of black bourgeois or liberal interracial movements. The ILD was not just one additional voice speaking out on behalf of poor blacks; it was a movement composed of poor blacks. It not only provided free legal defense and sought to expose the “class basis” of racism in the South, it gave black working people what traditional middle-class organizations would not—a political voice. 25

The Scottsboro case took many years to resolve. In 1937, four of the nine defendants were finally freed, and the last was not released until 1950.

The ILD’s strategy of organizing a mass, multiracial campaign to free the Scottsboro Boys was vindicated. Had the CP not quickly moved to organize a mass national campaign, the Scottsboro case would have quickly ended in a typical Southern lynching. Instead, it became a rallying cry against injustice and proof that Black and white workers could unite as a class in the fight against racism.

The CP in Alabama

The CP’s work in the South centered in Birmingham, Alabama. In conditions of repression comparable to Tzarist Russia, the CP was able to organize Black and white workers in fights for relief, for the Scottsboro Boys, and for union rights. It quickly earned a reputation among the Southern ruling class as a “race equality” organization. Nowhere was the relationship between class exploitation and racial oppression clearer. The Southern ruling class had developed a carefully constructed system of racial violence and segregation designed to exploit both Black and white workers more effectively. The CP was feared and hated because its call for Black and white unity and equality threatened to destroy this edifice.

The CP’s work in the South began when in 1929 it sent two white organizers into Birmingham. By the end of 1930, the Birmingham CP had grown to 90 members, and had recruited some 500 workers to “mass organizations.” By 1933, the Party had recruited almost 500 members, the majority of them Black workers. The CP’s membership in Birmingham alone peaked at 1,000 in 1934.26

Blacks who came around the CP were impressed by white Communist’s willingness to treat Black workers as equals. Writes CP activist Angelo Herndon, “We were called ‘comrades’ without condescension or patronage. Better yet, we were treated like equals and brothers.”

The Black Belt theory played no role in the CP’s work. Its gains were achieved by agitating around immediate issues of dire concern to Black workers: for unemployment relief, against legal injustices and segregation, for the right to organize unions, higher and equal wages, and an end to lynching.27

As in the North, the CP’s initial success centered around the fight for unemployment relief. The first demonstration for unemployment relief, held in Birmingham’s Capitol Park in May 1931, attracted 700 Blacks and 100 whites. On November 7, another demonstration was called which drew 7,000, mostly Black, unemployed workers.

The following year, a May Day demonstration called by the Birmingham CP attracted 3,000 workers. Police supported by White Legionnaires and Klansmen attacked the demonstration, but demonstrators fought back. A group of Black women who attended a Party meeting the next day “excitedly inquired as to the time and place of the next demonstration ‘because they wanted to whip them a cop.’”

These protests were impressive given the level of repression in the South at the time. Lynching was very common, and anyone organizing against racism or for union rights was targeted for violence by white supremacist organizations and the police, whose memberships most often overlapped. The number of KKK “klaverns” increased by 44 in 1934 alone. In response to a “Negroes Beware” Klan leaflet threatening Blacks to stay away from Communists, an ILD leaflet was issued warning “KKK! The Workers are Watching You!”

The state, in response to Communist activity, passed laws which banned the distribution of radical literature. Repression forced CP members to work underground. Meetings were held in secret. Black women disguised as laundresses would smuggle leaflets out of the homes of white Communists in laundry baskets. Party organizers hid copies of CP newspapers in hollow trees.

The worst repression was meted out against Black sharecroppers whom the CP organized into the Croppers and Farm Workers Union (CFWU) in 1931, and which grew to 800 members in a matter of months.

The union was smashed after a union meeting for the Scottsboro Boys in Camp Hill, Alabama, was dispersed by armed white vigilantes, who murdered Ralph Gray—one of the founders of the CFWU—and burned down his home. The remnants of the CFWU regrouped and formed the Share Croppers Union (SCU). In the face of massive, all-out repression, SCU sharecroppers were forced to disguise their meetings as “Bible” meetings and to arm themselves. CP leader Harry Haywood noted that sharecroppers came to meetings with “a small arsenal.”

Tensions came to a head again in 1932 in a town near Camp Hill, when 15 armed Black SCU members defended a debt-ridden farmer whose land was being seized. They engaged a sheriff’s posse in a shoot-out which left one SCU member dead and several wounded. In the wave of mass terror which followed, Blacks were forced to flee into the woods to escape roaming armed vigilante bands. James Clifford—wounded in the shoot-out—later died in jail after he was refused medical attention. A funeral procession held in Birmingham for the two slain SCU members drew 3,000 marchers and 1,000 onlookers.

In spite of this repression, the SCU at its height signed up over 8,000 sharecroppers, some of them white, but mostly Black.

In Birmingham, even more than in the northern cities, the CP was able for a time to position itself as the organization most concerned with the issues and demands of Black workers. In Birmingham the Black middle class was extremely moderate when it came to challenging segregation. There were virtually no other organizations other than the CP who made even a pretense of organizing Black workers and the poor for their rights. The CP therefore was practically, until the CIO came south, the only focal point of radicalization among Black workers. The CP came to be seen as the organization fighting Jim Crow racism. In Harlem, on the other hand, the CPs Third Period ultraleftism was more damaging, because it prevented the CP from calling for principled unity around immediate struggles which could have helped to win Blacks away from the nationalist Garveyites or the liberal NAACP—both of which had a larger, more influential presence among Blacks in Harlem.

The CIO and the Popular Front

The year 1933 marked the beginning of an upsurge in class struggle. Strikes tripled to 1,856 in 1934, and shot up to a peak of 4,470 in 1937.28 The strike wave was accompanied by an explosion of union organizing: membership rose from 2.6 million in 1934 to 7.3 million in 1938.

Black workers were a significant part of the workforce: 9.9 percent of coal miners, 18.9 percent of laborers in the iron and steel industry and 35 percent of longshoremen.29 Forced to take the dirtiest, lowest paid jobs, they also began joining unions in unprecedented numbers. In 1930, 50,000 Blacks were in unions. By 1940, half a million Black workers had joined unions. 30

Not long after Hitler’s victory in 1933, the Comintern made a complete about-face. Fearing a Nazi attack on the USSR, Stalin sought to create military alliances with Britain and France. In line with this new approach, the ultraleft Third- Period line gave way to its exact opposite: the Popular Front. The CPs were now called upon to unite with everyone—even bourgeois parties—to bring pressure to bear on the “democratic, anti-fascist” countries.

In the U.S., the CP suddenly became uncritical apologists for Roosevelt and the New Deal. Formerly denounced as a fascist, Roosevelt now became “the most outstanding anti-fascist spokesman within the capitalist democracies.” CP leader Earl Browder listed among Roosevelt’s accomplishments in 1937 the “enforcement of the rights of Negroes.”31

The Comintern’s turn to the Popular Front in 1935 coincided with the creation of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). The CIO was formed by John L. Lewis of the United Mine Workers (UMW) and a handful of other American Federation of Labor (AFL) union leaders who understood clearly the need to organize workers along industrial lines. Though Lewis had in the 1920s ruthlessly purged Communists and other militants from the UMW, the mass upsurge of unionization and strikes led him to the conclusion that, in order to organize industrial unions in Auto, Steel and Rubber, he would have to bring in the best organizers. The best organizers were members of the Communist Party.

The AFL was dominated by craft unions that refused to organize unskilled workers, native-born, Black and immigrant. Rather than challenging the divide-and-rule tactics of bosses, particularly in the South, the AFL leaders capitulated to racism and segregation.

The move by Lewis and others in the AFL to organize workers on an industrial basis automatically posed the question of organizing all workers—Black and white, immigrant and native-born—together. Without appealing to Black workers to join and be part of the new union movement, the CIO could not be successful.

By 1936, 40.3 percent of CP members were in unions, organized in over 600 shop nuclei.32 They became key activists and leaders in the mass organizing drives of the CIO. According to CP leader William Z. Foster, 60 of the 200 organizers who launched the Steel Workers Organizing Committee (SWOC) were Communists. And in the United Auto Workers (UAW) union, CP members on the shop floor and in the union locals played leading roles in the sit-down strikes. Black CP members and supporters were crucial in bringing Blacks into the CIO. Three of the first six Black UAW organizers had previous experience with the CP-organized Auto Workers Union. One SWOC organizer—a Black CP member who had led unemployment marches in the early ’30s—single-handedly enrolled close to 2,000 Black steel workers in the Pittsburgh area. 33

The hold of prevailing racist ideas meant that white workers did not automatically see the importance of antiracist unity of Black and white workers, but the upsurge of struggle provided the conditions for breaking down racism.

In some situations, white workers instinctively recognized that antiracist demands were at the root of strong solidaristic unions. White steelworkers joined with their black comrades in their “civil rights revolution” in the late 1930s in newly organized steel towns lining the Allegheny, Monongahela, and Ohio rivers, desegregating everything in sight, from restaurants and department stores to movie theaters and swimming pools.34

It is no exaggeration to say that CP militants played the most important role in initiating and leading these struggles to break down the barriers of racism between white and Black workers and bring Black workers into the new labor movement.

However, as the CP moved into its Popular Front phase it abandoned rank-and-file militancy in favor of accommodation with Lewis and the CIO bureaucracy. Indeed, Lewis’s condition for bringing in Communist Party members as union organizers—a condition accepted by the CP—was that they downplay their politics and behave merely as good activists. Though CP members were key leaders on the ground in the sit-down strikes, CP leaders backed Lewis’s efforts to put a stop to them. This tendency was reinforced by the CP’s orientation to acquiring leadership positions in the bureaucracy. According to Harvey Klehr, CP members led 40 percent of the newly-formed CIO unions.35 This orientation in some cases dampened the CP’s commitment to fighting racism.

So, for example, in New York’s Transit Workers Union, CP union leaders did not challenge the union’s refusal to include a nondiscrimination clause in its contract proposals in 1937 for fear of alienating conservative white workers in the union.36

The Popular Front did open the Party up to working with organizations that it had previously denounced and refused to work with. In Harlem, the CP was instrumental in organizing a 25,000-strong demonstration of Blacks and Italian-Americans against Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia at a time when anti-Italian sentiment was high in the Black community. The CP’s anti-imperialism, however, was tarnished when the New York Times revealed that Stalin was selling oil and other material to Mussolini’s government. A number of Blacks defected from the CP as a result of this revelation.37

The CP, in alliance with A. Philip Randolph and various Black liberal leaders and organizations, established the National Negro Congress (NNC). The NNC was crucial in helping to organize Black workers into the CIO and in bringing anti-racist issues into the labor movement. But with the NNC, the CP accepted a role as a furtive junior partner. In this and all areas of work, CP members were now expected to downplay at best, completely hide at worst, their membership in the Party, tailing their liberal allies.

The CP’s accommodation to Roosevelt and New Deal liberalism meant supporting the Democratic Party, which refused to challenge segregation for fear of alienating its Southern “Dixiecrat” wing. Roosevelt even refused to support anti-lynching legislation at a time when dozens of mob lynchings were being committed against Blacks every year—28 in 1933 alone.38

Southern New Dealers refused to challenge lynching, Jim Crow segregation or the restriction of Democratic primaries to whites only. That, however, didn’t stop the CP’s southern representative in the central committee, John Ballam, from proclaiming:

It is entirely within the field of practical politics for the workers, farmers and the city middle class—the common people of the South—to take possession of the machinery of the Democratic Party, in the South, and turn it into an agency for democracy and progress.39

The practical results of this new line—especially in the South—were astonishing. In 1937, the CP endorsed Alabama Democrat Lister Hill, an opponent, like virtually all Southern New Deal Democrats, of anti-lynching legislation.40 The CP’s weekly, Southern Worker—which had regularly run letters from Black workers describing their struggles and conditions—was dropped and replaced with New South, a “Journal of Progressive Opinion” designed to attract southern liberals. The ILD—the organization that had attracted thousands of Blacks across the country to its militant work around the Scottsboro case and others—was disbanded summarily in 1937, and all CP members were ordered to join the NAACP. Though its membership shifted leftward under the influence of the upturn in class struggle, the NAACP remained committed to lobbying and legal efforts to secure modest reforms.

In 1937, Communist organizers for the National Job March to Washington failed to appoint Black stewards and refused to appoint Blacks to delegations lobbying Congress, for fear of embarrassing southern supporters of expanded relief.41

The Stalinist opportunism of the CP disillusioned many Black members who had been attracted to the CP’s work against racism. Though the Party continued to grow, its political zigzags, dictated by the bureaucracy in Russia, ultimately compromised and undermined its commitment to fighting racism. The CP’s credibility was further eroded when in 1939, as a result of the Hitler-Stalin pact, the party again reversed its policy of united front work and began denouncing Roosevelt again. With Hitler’s invasion of Russia, the party again became Roosevelt’s biggest cheerleaders, calling on Blacks to subordinate their demands for integrating the army and war production industries to the success of the war effort—even supporting the placement of Americans of Japanese descent into concentration camps.

Conclusion

It is commonly asserted that the CP subordinated the fight for Black freedom to Stalin’s foreign policy. The problem is that for most critics, this is seen as a failure not of Stalinism, but of Marxism. Nothing could be further from the truth.

The party’s abandonment of militant Black struggle went hand in hand with its support for Roosevelt, its accommodation to liberalism, and its turn away from the working class—in short, its abandonment of Marxism.

Some left-wing historians argue that the popular front was a major step forward because it brought the CP out of its isolation and into the mainstream of American politics. Some, on the other hand, are more attracted to the Third Period because of the CPs ultra-militancy. The truth is that in both periods the CP—tied as it was to the dictates of Stalin—had ceased to be a party committed to moving the class struggle forward in the U.S. In its ultraleft Third Period, it squandered any possibility of building genuine united fronts. In the Popular Front period, its unprincipled alliance with liberals and uncritical devotion to Roosevelt channeled the radical impulse of tens of thousands of workers away from revolutionary politics.

Revolutionary Marxists have always been at the forefront of fighting racism. At the center of Marxism is the idea that workers—the majority of society, multiracial in composition—can only achieve their emancipation if they unite against their common oppressors and exploiters. It is because of this vision that socialists have always placed fighting racism at the forefront. Without a consistent fight against racism, a unity based on equality cannot be achieved. Without overcoming the divisions which ensure capitalism’s rule—of which racism is the most poisonous—the working class cannot liberate itself.

The importance of the CP’s work in the 1930s—in spite of Stalinism—is that it showed that such a fighting unity is possible in the United States. Had the CP been a genuine revolutionary party going into the Depression, one which combined a commitment to fighting racism with a willingness to unite with other forces not yet won to revolutionary ideas, it could have grown even more massively, decisively winning workers—both Black and white—away from New Deal liberalism, the NAACP and the cul-de-sac of Black nationalism. Because it wasn’t, an opportunity of great proportions was lost. If we understand both the CP’s achievements in fighting racism and the reasons for its ultimate shortcomings, socialists today can learn valuable lessons in the fight against racism and for socialism.

Robert A. Gorman, “Black Neo-Marxism,” Rethinking Marxism, Winter 1989 , pp. 120-123. These ideas are common on the left and have a long history. A number of Blacks who became disillusioned with their experience in the Communist Party—for example George Padmore, founder of the Pan Africanist movement, and acclaimed author Richard Wright—have equated the CP of the 1930s with Marxism and have drawn conclusions similar to Gorman’s that Marxism “fails” Blacks.

- Philip Foner, British Labor and the American Civil War (London: Holmes & Meier, 1981), p. 113.

- Letter to Meyer and Voght, Writings Vol. 3 (New York: Vintage, 1977), p. 169.

- V.I. Lenin, “The Socialist Revolution and the Right of Nations to Self-Determination,” Collected Works, Vol. 22 (Moscow, 1976), pp. 147-148.

- Philip Foner and James S. Allen, Eds., American Communism and Black Americans (Temple, 1987), p.3. Actually, two communist parties were formed in 1919—the Communist Labor Party and the Communist Party, which merged in 1921.

- Foner and Allen, op. cit., p. 9.

- Philip Foner, Organized Labor and the Black Worker, 1619-1981 (New York: International Publishers, 1981), p. 149.

- Tony Cliff, The Darker the Night, the Brighter the Star: Trotsky: 1927-1940 (London: Bookmarks, 1993), p 110.

- R. J. Alperin, Organization in the Communist Party, United States, 1931-1938 (Doctoral Dissertation, Northwestern University, 1959), p. 49.

- Sharon Smith, End of the American Dream: The U.S. Working Class at the Crossroads (unpublished manuscript), p. 45.

- Alperin, op. cit., p. 32.

- Harvard Sitkoff, A New Deal for Blacks, (Oxford, 1978), pp. 36-37.

- Foner, op. cit., p. 200.

- Sharon Smith, op. cit., p. 43.

- Alperin, op. cit., p. 60.

- Harvey Klehr, The Heyday of American Communism (Basic, 1984), p. 332.

- Foner, op. cit., p. 196. Rhonda Levine, Class Struggle and the New Deal (University of Kansas, 1988), p. 54.

- Mark Naison, Communists in Harlem During the Depression (New York: Grove Press, 1974), p. 78.

- Sharon Smith, op. cit., p. 38. This was not the worst incident. On February 16, 1934 —after Hitler’s victory in Germany—5,000 CP members led by Robert Minor and Clarence Hathaway, the editor of the Daily Worker, broke up a mass socialist rally in New York called to protest the slaughter of Austrian workers by the fascist chancellor Dolfuss. There can be no doubt that activities like these demoralized militants in the CP and revolted potential supporters. [Fraser M. Otanelli, The Communist Party of the United States (Rutgers, 1991) p.56].

- Naison, op. cit., p. 60.

- Dan T. Carter, Scottsboro: A Tragegy of the American South (Louisiana State, 1994), p. 52.

- Robin Kelley, Hammer and Hoe: Alabama Communists During the Great Depression (Chapel Hill, 1990), p. 84.

- Carter, op. cit., p. 144.

- Kelley, op. cit., p. 90.

- Ibid., p. 91.

- Material for this section comes from Kelley, Hammer and Hoe, except where indicated. Kelley’s book on the CP in Alabama and Naison’s book on the CP in Harlem are by far the best books on the CP in the 1930s, and much of the material for this article relies on them.

- Otanelli, op. cit., p 39.

- Alperin, op. cit., p. 29.

- Ibid, p. 33.

- Foner, op. cit., p. 231.

- Klehr, op. cit., p. 207, and Otanelli, op. cit., pp. 114-115.

- Alperin, op. cit., pp.53-55.

- Foner, op. cit. p. 219.

- Mike Goldfield, “Was There a Golden Age of the CIO?” Trade Union Politics, American Unions and Economic Change 1970s-1990s (Humanities Press, 1995), p. 88.

- Klehr, op. cit., p. 238.

- Naison, op. cit., pp. 265-266.

- Naison, op. cit., p. 157. Wilson Record, The Negro and the Communist Party (Athaneum, 1951), p. 139.

- Sitkoff, op. cit., p. 288.

- Kelley, op. cit., p. 177.

- Ibid, p. 134.

- Naison, op. cit., p. 264.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Google+

Google+ Tumblr

Tumblr Digg

Digg Reddit

Reddit StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon