100 issues of the International Socialist Review

We are pleased to introduce the hundredth issue of the International Socialist Review, which comes out just short of the publication’s twentieth anniversary.

The ISR began in 1997 as a quarterly magazine, moved to a bimonthly in 2000, and in 2013 was relaunched as a quarterly journal. Its first editorial announced our intention to “arm a new generation of Marxists with the lessons of past struggles as well as the theoretical means to tackle new ones.” The editorial introducing the quarterly stated that it intended to publish “theoretical and analytical pieces…to take up important questions facing the Left in today’s radically changing world.” We remain committed to that goal.

Readers of the ISR will know that we consider Marxism to be, to paraphrase Marx, the most effective means to both interpret the world and to change it. We hold to its basic materialist premises: Social relations, class division, and oppression are shaped by the level of development of society’s productive forces; and that capitalism has created the material means—provided that a mass, self-conscious movement of the majority successfully challenges it—for a new society free of class division and oppression to be born. Central to our politics is the insistence, along with Marx, that socialism cannot be delivered from above—that “the emancipation of the working class must be the act of the workers themselves.”

In the words of the editorial of the first issue of International Socialism in Britain (1958), a publication that developed many elements of the political tradition that shaped the ISR, our goal is to make “a small contribution, to Marxist thought… to bring the traditions of scientific socialism to bear on the constantly changing pattern of class struggle.”

We by no means consider Marxism, however, to be a closed book. Capitalism has certain key features that are traceable throughout its history, but is also by its nature dynamic and changing. As the Russian revolutionary V. I. Lenin wrote in 1897, a hundred years before the first issue of the ISR, “We do not regard Marx’s theory as something completed and inviolable; on the contrary, we are convinced that it has only laid the foundation stone of the science which socialists must develop in all directions if they wish to keep pace with life.”

As a set of ideas developed in the cauldron of struggle and constant change, Marxism both reacts to and reacts back upon those developments. For example, deeper Marxist insights into the role of the family and social reproduction came after the rise of the women’s movement in the 1970s, and continues to be developed on the pages of this journal as well as other venues. The same can be said for the Marxist analysis of LGBTQI oppression, disability oppression, and many other questions, not the least of which is the relationship between race and class. These are not peripheral questions; they are fundamental both to understanding how capitalism works and how a united working-class movement can be developed to overthrow it.

A great deal has changed in the world over the past several decades, changes that have raised many questions for the radical left. Some of them harken back to an earlier stage of capitalism; others are completely new: The global restructuring of capitalism (and of the world working class) and the emergence of China as a world economic powerhouse; the collapse of the Soviet Union, and alongside it, the demise of state-directed development and the rise of neoliberal capitalism; the emergence of the US as the “sole” superpower, only to give rise to burgeoning “unipolar” if still asymmetric conflicts; the replacement of “anticommunism” with the “war on terror” and its concomitant Islamophobia as a mobilizing ideology; the return with a vengeance of capitalism’s boom-bust cycle as the neoliberal phase of capitalism runs into increasingly apparent contradictions; global climate change and the qualitative acceleration of multiple environmental disasters; a sustained decades-long assault of the union organizations and living standards of the working class worldwide, coupled with the decline of the former mass communist parties and the adaptation of social democracy to the logic of neoliberal capital; the attempts, with varying degrees of success, to create new broad left anti-austerity parties aiming to fill the void left by the demise of CPs and social democracy; the explosive emergence of revolutionary anti-dictatorship movements in the Middle East, only to be quickly replaced by imperialism-fueled sectarian rivalry and civil war.

These developments have raised a whole host of new questions that are, and should continue to be, the subject of important investigation, analysis, and debates: the relationship between state and capital; the nature of imperialism, and in particular US imperialism, in an era of globalization; the assault on the working class and the changing conditions and character of labor in the neoliberal era, and its impact on working-class organization, power, and consciousness. For some, these developments have driven an analysis that no longer sees workers as the force capable of transforming the world. But any project that aims to challenge capitalism and look beyond it cannot but take into account the international working class which, though fragmented and relatively disorganized, remains the lifeblood of the system and is in fact bigger than it has ever been globally.

The question of the capacity of the working class to transform society, moreover, is intimately related to another question—that of how socialists and revolutionaries should be organized today, particularly the relationship between the organization of revolutionaries as revolutionaries and their relationship to a wider movement, such as how they relate to the emergence of broader anti-capitalist political parties.

We are living through complex and contradictory times. In 2008, world capitalism experienced its worst economic crisis since the 1930s—and after some years of recovery, the threat of recession looms large again. The crisis has opened up a period of economic instability, of geopolitical rivalry and renewed wars, of political volatility, and of struggle, some of revolutionary or near-revolutionary proportions. But it has also brought us great defeats, exemplified most starkly by the onset of counterrevolution and sectarian violence in the Middle East. Though this crisis has created an opening for radical politics to begin to emerge again, resistance is not yet of a sufficient size, level of organization, and political weight to challenge the ruling-class offensive. Moreover, the rise in popularity of far-right forces show how the mass disillusion in traditional politics leads not only to radicalization to the left, but also to the right, as the wave of xenophobia toward Muslim refugees in Europe and the US shows.

That polarization is expressed in the United States today in the emergence of Donald Trump as the leading GOP candidate on the one side, whose campaign consists of a series of racist and xenophobic diatribes; and the emergence on the other side of Bernie Sanders, a self-described socialist, as a Democratic Party candidate, who emphasizes New Deal liberal policies long ago abandoned by the Party.

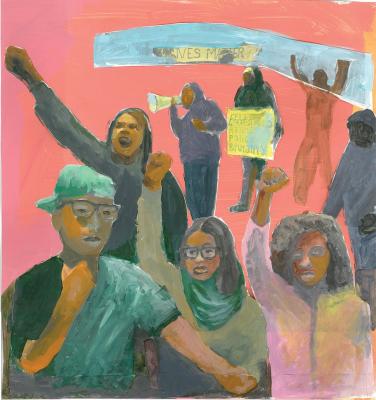

The most peculiar and encouraging feature in the current period is the clear end of the stigma associated with socialism in the United States. “Socialism” was the most looked-up word in the Mirriam-Webster online dictionary in 2015, a sign, according to its site, that “the term has moved beyond its cold war associations.” A January poll showed that 43 percent of likely voters in the Iowa Democratic caucuses would use the word “socialist” to describe themselves—as against the 38 percent who described themselves as “capitalist.” Even if the conception of it is vague and relatively undefined, there is no doubt that it reflects the frustration and anger that millions feel against the billionaires who recklessly run our society. It reflects a vague but real sentiment among millions that people’s needs should be put before profit, and that wealth should be distributed more fairly. The rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, and, to this point, its persistent reemergence in various forms across the country, is another sign of the emerging new radicalization across the United States.

There is still a considerable gap between the crying need to overcome capitalism and the still puny resources of the radical and revolutionary left. What is certain is that any effort to rebuild a vibrant left culture in the United States depends not only on engaging with day-to-day struggles as they emerge, but in creating spaces of debate and dialogue on the left which can help shape a clear understanding of the world and the means by which it can be transformed.

••••

We think that the articles in this issue 100 exemplify the spirit of engaged inquiry that we’ve tried to encourage. The articles can be broadly grouped around three themes: the struggle against racism; the nature of imperialism; and the question of the left and broad parties.

Antonis Davanellos, a leader of the International Workers’ Left (DEA) in Greece, returns to the pages of the ISR with a piece that reviews the experience of revolutionaries inside Syriza, concluding that “the forces of a Marxist and anti-capitalist Left, when (and where) they make the choice to participate in ‘broad parties,’ must do so in a specific way: By maintaining their ideological and organizational autonomy, and maintaining their freedom and ability to criticize and distance themselves; by taking the time and energy to form a left wing, and by giving it a program orientated on the class struggle.”

Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor’s contribution, an excerpt from the introduction to her new book From #Black Lives Matter to Black Liberation, examines the conjuncture between the rise of a new movement challenging racism in a society that claims to be “post-racial,” and the growing divide between an established Black elite and increasing poverty, unemployment, and brutalization for the majority of African-Americans.

Brian Kelly’s article on W. E. B. DuBois investigates, through the lens of a discussion of Black Reconstruction and what he called the slave’s “general strike,” the role that Blacks played in their own emancipation.

In her interview Donna Murch, who is the author of Living for the City: Migration, Education, and the Rise of the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California, discusses the origins and some of the successes and failures of the Black Panther Party—topics increasingly relevant to the new anti-racist movement developing in the United States.

Phil Gasper’s article on Lenin and Bukharin’s theories of imperialism—now about 100 years old—outlines these theories and evaluates the ways they continue to be relevant to understanding the world system. “It is obviously true that one cannot understand the complexities of contemporary geopolitics and imperialism simply by reading Lenin and Bukharin,” he notes. “But it is equally true that if one ignores their key insights, it is not possible to make much sense of the otherwise bewildering set of events that is currently being played out on the international chessboard.”

In a companion piece, Ashley Smith looks at the “international chessboard” of modern imperialism, and in particular, the way it is currently playing out in the Middle East, arguing that though the US remains the overwhelmingly dominant military power, it faces a world where its dictates are increasingly challenged by rival powers, in what he calls an “asymmetric multipolar world order.”

Eric Blanc’s “Anti-imperial Marxism,” reexamines the evolution of the debates on the question of national oppression in the socialist movement of the Russian empire, particularly in its “borderlands,” before the 1905 revolution, and makes the case that the politics of these socialists had an impact on the evolution of Lenin and the Bolshevik Party’s thinking on these questions, which, he contends, in this earlier phase had important limitations.

Finally, we reprint Duncan Hallas’s article, “Toward a revolutionary socialist party.” Though written in a significantly different time and place, this piece, we believe, should be an important reference point for socialists who are engaged in debates on the role of revolutionaries today. The piece lays out in refreshingly undogmatic ways the concept of revolutionary organization not as a self-proclaimed “vanguard” standing apart, but as “an organized layer of thousands of workers, by hand and by brain, firmly rooted amongst their fellow workers and with a shared consciousness of the necessity for socialism and the way to achieve it.” Hallas’s opening statement, that the “events of the last forty years largely isolated the revolutionary socialist tradition from the working classes of the West” remains, for a whole host of reasons, still true today, though what is not yet clear is the means by which class struggle will reassert itself, and with it, the regeneration of new possibilities for creating revolutionary parties of the working class. Until then, we prepare the ground.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Google+

Google+ Tumblr

Tumblr Digg

Digg Reddit

Reddit StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon