Resistance and reaction in the time of Trump

US politics in the past months has experienced, to quote the Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky, “an abrupt turn in the objective situation.”

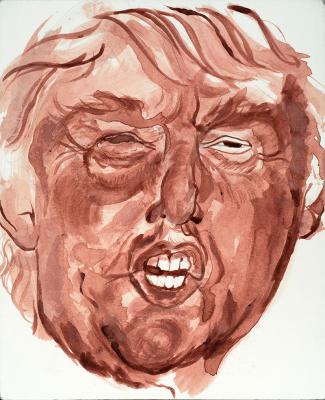

Very few of us on the left expected that the next president of the United States would be a corrupt, narcissistic billionaire swindler, an open sexist and self-confessed serial abuser, and a man the Far Right hails for his open racism and nationalist xenophobia. Donald Trump successfully positioned himself as a right-wing populist, anti-establishment candidate who would tear up free trade, deport immigrant “job-stealers,” and restore good jobs for “real” Americans. And it worked.

Democrat Hillary Clinton positioned herself as the bland realist candidate of the status quo (“America is already great”). She thought that she could take the votes of women, workers, Blacks, and immigrants for granted. The “clear favorite of the US capitalist class,” as Charlie Post’s essay in this issue notes, Clinton loudly touted her establishment support. She thought she could win by pointing at Trump and saying that she wasn’t him. But her lackluster campaign failed to shake her popular image as a friend of Wall Street.

As is now well known, Clinton actually won the popular vote by almost 3 million votes, making her the fifth presidential candidate in US history to win the popular vote while losing in the electoral college, an eighteenth-century institution designed to cement the political power of Southern slaveholders. The election hinged on a margin of about 77,000 votes in several “rust-belt” swing states. As Post points out, Trump’s victory had less to do with a groundswell for him as it did with “a sharp drop in the participation of traditional Democratic voters.”

But the degree to which Trump won working-class votes should not be exaggerated. As Post points out, while a small percentage of union households shifted to Trump compared to 2012, “The core of Trump’s support, like that of the Tea Party since 2009, is the older, white, and suburban/exurban middle classes.” His non-college- educated backers were concentrated, Post notes, among small businesspeople and managerial employees.

The fact, however, that Trump did not receive a popular mandate does not mean he will refrain from acting as if he got one. To be clear, some of his campaign promises—for example, his promise to “drain the swamp” in Washington—have already been violated. His main cabinet picks of retired generals, Wall Street insiders, and an Exxon CEO might have been plucked from the Washington swamp. His other agency appointments are the equivalent of “putting arsonists in charge of fighting fires,” as Michael Brune of the Sierra Club put it when discussing Trump’s choice of anti-environmentalist Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt to head the Environmental Protection Agency.

With a GOP congressional majority, Trump’s ascendancy clearly does not bode well for Muslim rights, civil liberties, abortion, immigrant rights, environmental regulation, and a host of other issues. Nor does it, despite his populist rhetoric, bode well for workers, white and non-white, union and non-union. His election has already emboldened Republican-dominated state legislatures to push through anti-abortion, right-to-work, and other draconian measures, and has also given confidence to the extreme right, as evidenced by their increased recruitment and the substantial rise in hate crimes against Muslims and others.

Trump’s win fits into an international pattern of a rising right-wing and far-right populism that plays off mass discontent over the failures of neoliberalism and diverts it toward nationalist xenophobia and anti-Muslim hysteria. The pattern reflects an increasing political polarization based on several factors: the weakness of the recovery from the 2007-08 financial crisis for the majority of workers; rising levels of economic and social inequality with obscene extremes of poverty and wealth; an ideological crisis of neoliberalism; and the subsequent delegitimation of the traditional political parties of the right, center-right, liberal, and vaguely social-democratic mainstream that have presided over these policies for decades.

The atomization and weakness of the trade union movement—and the lack of any organized political option emphasizing a program of social solidarity—has also made some workers in the US, Europe, and elsewhere more open to racist and nationalist appeals, as the 2016 vote in Britain to leave the European Union, the rise of far-right parties and politicians in Europe, and other examples show. As Neil Davidson writes in his piece assessing the growth of right-wing populism,

The revival of the far right as a serious electoral force is based on the apparent solutions it offers to what are now two successive waves of crisis, which have left the working class in the West increasingly fragmented and disorganized, and susceptible to appeals to blood and nation as the only viable form of collectivism still available, particularly in a context where the systemic alternative to capitalism—however false it was—had apparently collapsed in 1989–91.

The extent to which the rise of this wave of right-wing populism represents a paradigm shift away from orthodox neoliberalism toward a new period of heightened economic nationalism, or to some hybrid of protectionism combined with a continued emphasis on neoliberalism’s classic domestic agenda of social cuts and increased “flexibilization” of labor, is still open to interpretation. These differences in emphasis express themselves in this issue of the ISR in the Post and Davidson essays.

While Trump’s victory may have been unexpected, it didn’t come in a vacuum. It followed after eight years of disappointment in the high expectations among many that Barack Obama would bring significant change. But President Obama initially focused on bailing out Wall Street, with little or no relief to distressed homeowners or unemployed workers. His signature legislation, the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare)—was a gift to the private health insurance and pharmaceutical industries.

Instead of stimulus spending on needed social services, Obama agreed to massive social spending cuts while maintaining most of the Bush-era tax cuts for the rich. He deported more immigrants than his predecessor; orchestrated a coordinated national police action to shut down the 2011 Occupy camps; executed thousands of people worldwide using unpiloted drones; failed to close the Guantánamo Bay prison camp; upped the assault on whistleblowers; presided over the ratcheting up of oil and gas production, pipelines, and fracking; and did little or nothing to seriously address the racial imbalances in the criminal justice system or the epidemic of police shootings that gave rise to the Black Lives Matter movement.

As Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor explains in her interview on the election and its impact on Black politics in the United States, “Black voters were not going to vote for Trump because he’s openly racist, but their disappointment in the Democrats meant that many stayed at home.”

Although Trump’s election has filled the Right’s sails, it would be wrong to conclude that the political period is simply one of growth for the Right. Political polarization also means the potential for the growth of resistance, and of the Left. One could see this in the emergence of Occupy and Black Lives Matter, the surge in popularity of the Bernie Sanders Democratic primary campaign, the support for “socialism” among young people, and the outpouring of solidarity and support for the resistance to the Dakota Access Pipeline at Standing Rock (see the articles by Ragina Johnson and Sarah Rougeau in this issue).

Sanders’s popularity in the primaries showed that there is a big opening for a more left-wing, pro-working class progressive political alternative. As Lance Selfa argues in his assessment of the Sanders campaign, for a brief moment a national candidate “spoke directly to the realities of class inequality.” Unfortunately, Sanders used this platform to swing his supporters behind Clinton.

The outcome of the 2016 election stunned millions of people. But it has also outraged many. Spontaneous outpourings of protest and student walkouts immediately followed the election, and a huge turnout was expected (as we went to press) at a January 21 women’s rights march called to protest Trump’s inauguration. There can be no doubt that the comprehensive nature of the attacks coming down raises the possibility (or, more appropriately, the necessity) of a resistance capable of linking issues and struggles in a way that facilitates united fronts between people who, in the past, may have seen social struggles as separate, single issues.

Resisting whatever attacks the Right plans to dish out isn’t sufficient. We must offer an alternative to politics as usual. This alternative will have to build on the politics of class solidarity, linking the fight against economic inequality with the fight against all forms of oppression. It must offer an alternative vision of a different kind of society, and raise its banner independently of the two parties of capitalism.

As Taylor argues at the end of her interview, Trump has “put immigrants, Muslims, women, African Americans, LGBTQ people, and unions in the cross hairs. . . . The idea that we will be able to defend ourselves from these kinds of concerted attacks from the state separately from other groups of people is nonsensical.” She continues:

There actually has to be a political argument articulated for solidarity, and not just solidarity because it’s good and makes us feel better about ourselves, but because it is an indispensable political strategy for us to defend what we have, let alone to mount a movement for reform.

It is difficult at this stage to predict exactly how events will unfold. We don’t yet know the full nature of Trump’s domestic and foreign policy; the kinds of debates and schisms (not to mention scandals) that will develop at the top; or whether the ruling class will coalesce around a new post-neoliberal nationalism or combine elements of neoliberalism with something new.

What we do know is that while the Right operates from a position of power and confidence, our side has been put on the defensive and is still weak. This puts a premium not only on patiently, but insistently, building the largest fight-back possible along a number of different fronts; it also puts a premium on building a left that can pose a political alternative to capitalism. That in turn necessitates a serious examination of our politics, our theory, and our historical tradition.

In that light, taking stock in 2017, the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution takes on an added importance. The lessons of that momentous period in world history—the high point of working-class power before the workers’ state fell to the pressures of imperialist encirclement and material privation—are ones that the pages of the ISR intends to explore over the year and beyond. The reprint of an analysis of the early phase of the revolution by Karl Radek in this issue contributes to that discussion.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Google+

Google+ Tumblr

Tumblr Digg

Digg Reddit

Reddit StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon