We have always been here

There were no stars that night. Just the glare of floodlights bouncing off low-hanging clouds and the cooking smoke from kitchens that were still serving dinner. It was one of the last nights before it got dangerously cold, before blizzards would blanket the camp in twenty inches of snow. Frost that crunched under your boots in the morning melted by midday and tracked little cakes of mud and dried grass into every tent and sleeping bag.

Shoulder to shoulder, hundreds gathered around the sacred fire at Oceti Sakowin camp, gripping Styrofoam cups of coffee and heating pads. The emcee, a Lakota man who had been giving announcements day in and out, took a moment to point up to the sky, “Let’s welcome DAPL security joining us tonight”. A low flying unmarked airplane whirled in and out of the clouds above us and everyone clapped and whooped like it was a special guest. People took out their flashlights and followed the shadowy plane like a fish in a dark lake. It had been circling the camp for weeks, mostly flying low to keep water protectors up at night.

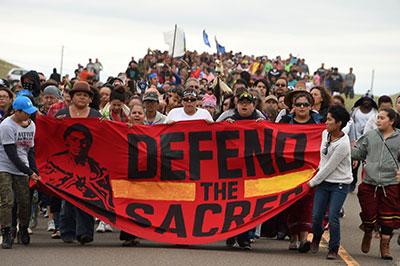

There was a line of headlights coming through the North Entrance and down Flag Road. The camp swelled to 15,000 over Thanksgiving weekend as people gave up comfortable holiday meals with their families to join the fight for Native rights at Standing Rock. They had watched in horror as the Morton County Sheriff’s Department spent $17 million in violent militant repression of Native American’s standing up against the Dakota Access Pipeline. They came because they were asked to, time and time again through live videos shared on social media, on conference calls, and at rallies that gathered like storms on the steps of the Army Corps of Engineers.

It had been a week since the November 20 incident at Backwater Bridge, the night when Morton County weaponized water itself and for hours sprayed over 400 people with water cannons in subzero temperatures. All for trying to remove burned-out vehicles left on the bridge by police and the National Guard after their attack on Treaty Camp.

Icicles glimmered on razor wire that night. Hypothermia cases overwhelmed the medics. A woman was blinded by a shot to the eye and another had her arm obliterated by a direct hit from a concussion grenade. These shots had reverberations across the country.

Now water protectors came for the warmth of the sacred fire and the pop of the large drum that bounced with every hit. For most of the Natives, the powwow songs were long familiar—“When we did the round dance/You were smiling/To the end of that sweet song.” Non-Natives who had never felt the powwow drum in their chests jumped at the chance to circle in a round dance. Three elders were taken by the music and popped invisible eagle feathers in the air. Every song was a victory.

Here along the shallow river banks was a sprawling village complete with seven kitchens, a children’s school, an extensive medical center, an art studio, and several meeting halls with hourly schedules. There were traffic directors, construction sites, a garbage collection crew (self-named “The Lost Boys”), and a security team that spoke into walkie-talkies in code names.

At its peak, 15,000-20,000 people lived and worked at the Oceti Sakowin and Sacred Stones camps. You could get lost from one side to the other in a day as new tents were put up, old tents collapsed, and new pathways worn in. The usual landmarks were “the green tent with such and such flag” or “the beige van next to the porta pottys.” If you had been there more than a few days, you could recall the smaller camps by name—Lower Bruhle, Red Warrior, Two-Spirit, the International Youth Council, and so on. You might even know there was a second sacred fire at the Headsmen camp.

Each day starts with a water ceremony at 6:00 a.m. Each meeting begins with a prayer. You take these opportunities throughout the day to remember that you and the people standing next to you are all fighting for a sacred land and water, and you speak of it in the language of the Oceti Sakowin (the original name of the Sioux Nation). You pray under the banner “Mni Wiconi,” water is life, because the Oceti Sakowin have used this place for ceremony since time immemorial, and downstream are several million people who depend on this waterway for their drinking water. The fight is very literally life or death.

The prayer gives you a break in the hustle and bustle to ground yourself again, and offers you the courage to fight another day. To survive the coming cold you must be able to depend on your neighbor and they on you, until the pipeline, this “Black Snake” of Oceti Sakowin prophecies, is dead in its tracks. At the end of Lakota prayers, they say, “Mitakuye Oyasin,” meaning “We are all related.” It is solidarity in action borne of necessity.

I traveled with the International Socialist Organization twice to Standing Rock. By December 5, the date that Governor Jack Dalrymple had promised to evict the residents of Oceti Sakowin camp, the ISO had sent seven contingents to stand in solidarity and report the actions on the ground. Many more members participated in their own cities in local actions that drew hundreds to thousands of people out into the streets to protest the Dakota Access Pipeline.

In the past several months we watched as solidarity blossomed across the country and internationally. Several thousand individuals came to the camp with cars and trucks packed with donations, some coming with their whole families, and others making new ones around the campfire. Over a million people had “checked in” on Facebook after reports that police were using Facebook to monitor activists coming to Standing Rock. In November, 500 clergy traveled together to bear witness and offer support, and on December 4 over 3,000 veterans self-deployed to act as front line support for water protectors.

The audacity with which Governor Dalrymple delivered the eviction notice, with airs of concern for water protectors’ safety in the winter cold, was both laughable and infuriating. Around the sacred fire one woman joked, “I’m not worried about the fifth. My birthday is on the fifth and nobody’s making me miss my party!” But in a much more serious tone during a press conference on the eviction, Ladonna Bravebull Allard, founder of the Sacred Stones camp, rebuked the governor, stating, “Our homelands have always been here. We have always been here. We know how to live in winter,” and “You weren’t concerned last year or the year before that.”

Certainly the Governor wasn’t concerned with the brutality meted out by Morton County police and the policemen from the other twenty-

four police departments that came from sixteen cities and ten different states to beat, stun, shoot, and tear gas people on sacred land. He wasn’t concerned when a wild fire burned through the night near camp without emergency services for over five hours. He wasn’t concerned that so many Standing Rock Sioux members had died from the cold over the last several years because of lack of quality housing.

The 3,000 veterans who arrived were concerned. Many had family members who served in the military for generations, and a great number of people already on the front lines were veterans. Native Americans continue to be the largest ethnic group recruited into the military, and so it seemed natural that veterans would take part in the struggle. People on the ground spoke of them as a “standing army,” a front line of defense, and it gave them renewed confidence to face down the militarized police.

On arriving in droves after some of the first heavy snow in December, the veterans spoke of the feeling of coming into a war zone. Water protectors who huddled in the nearby casino for warmth looked like refugees in Iraq. The police, hunkered down behind LRAD’s, razor wire, and grenade launchers, were more equipped than soldiers in Afghanistan.

Just as the vets were arriving the state changed its position, lifting the eviction notice. In its place it promised a heavy fine on anyone traveling to camp, even though the police had long since profiled anyone who looked remotely Native American or a supporter of the camp. At a prayer action at the Bismarck Mall on Black Friday, a man was arrested for “smelling like campfire.” At a restaurant in Mandan, two women were intimidated and forced to leave by police for wearing a #NoDAPL button. The threat of a fine was just a legal cover to intimidate and threaten supporters.

On December 4, the day before the now defunct eviction, the Army Corps of Engineers stated that they would not grant Dakota Access the permit needed to drill under the Missouri River. ISO members from New York were on the ground when the news rippled throughout the camp. Songs and prayers erupted all over. There was dancing, hugging, crying. As night set in, the bursting of fireworks replaced the drone of the DAPL plane. Some raised reservations that the permit denial was just another trick to empty the camp, but overall the celebration was infectious.

Questions arose about the way forward, but around the country people celebrated with the affirmation that—at least this much, we have won. Legally, it is not going to be easy for Dakota Access to recover from the loss of time and money, regardless if any future decision grants them the permit. Already DAPL’s stocks have plummeted to near junk level, and international funders have pulled out money left and right. The company loses millions every day that oil isn’t flowing through the pipeline. While the head of the snake hasn’t been cut off, it certainly has been dealt a critical wound.

Beyond Standing Rock, people desperately needed such a win. After a devastating election period between two of the least popular candidates of all time, Donald Trump looming over the White House promises another four years of brutal struggle on all fronts. And yet, despite all the assumptions and dismissals about the US working class as being irredeemably racist and backwards, the struggle in Standing Rock has brought together the largest show of solidarity in recent memory. Not only were people able to survive the fight for almost a year, they actually built a thriving community of tens of thousands.

The experience at Standing Rock, like the encampment itself, was massive, ever shifting, and inspiring. The arrival of the veterans was clearly the most celebrated for its strategic timing and its ability to take on the threats of the police and the state head on. But it would not have been possible without the thousands of people who built small victory after small victory, often unseen or unreported. The strength of unarmed water protectors who walked out to a line of police and prayed for the water. The ability to build an expansive medics’ village, the hard work of installing stove pipes in tepees, the donations of several tons of fresh food, and the individuals who cooked day in and day out. The people who offered their skills and services in any way possible to keep each other warm and fed and healthy.

During my short time there I caught wind of a meeting organized by Rebecca Nagel and Graci Horne of Native women who had survived rape and abuse. There I met dozens of Native women who I had first seen around the sacred fire, or walking throughout the camp. We spoke of our own stories, of the epidemic of sexual violence in Indian Country. We also spoke of the oil workers camp, called “man camps,” that came and went with every pipeline. Native women were trafficked into these camps, often abused and disappeared without a word. Long hours retraced these stories that have been relived for generations. Through our stories we could hear the drums and the songs, announcements from the fire. Some spoke in their own language. We learned the Lakota word for friend, “mishgaye,” which was unlike the English connotation of an acquaintance and more like a sacred partner in life.

We planned to march the next day from the Rosebud camp, across the river, to the sacred fire at Oceti Sakowin. There were around fifty of us and we were welcomed to Rosebud camp by Mni Wiconi, the baby girl born at Standing Rock, wrapped in soft blankets in her mother’s arms. Donning purple shawls and turquoise fleece scarves, we were led by Spirit Riders on horseback to deliver our message—that woman and water are sacred. We held up red quilt squares that carried the messages of survivors and their supporters, connected to the larger Monument Quilt campaign, and long banners written in Lakota.

As we walked the lone road leading to camp, you could see small specks of people along the fence turning to look at us. We walked silently at first, with a few murmurs of nervous laughter, and then a chant slowly moved through the line. As we walked through the North Entrance our voices were booming, “Women and Water are Sacred!” The sound echoed across camp and bounced back to us from the hills.

Over a thousand people watched as we approached, and one by one fists rose in the air. Men in regalia who were speaking at the mic took off their headpieces and made room for us. A path opened and all around people gave their attention and hearts to us; so many women who had been kept in silence for too long. So many women that looked like others who would never be able to return to their families. So many women who survived a long unspoken legacy. They stood with us.

I couldn’t wipe tears from eyes, nor did I want to. I was comforted to think of the words of Tomas Karmelo Amaya from Indigenous Rising Media who said, “The frontlines are here also.” We formed a circle around the fire, and let our prayers go up in the flames, led by a song of an Indigenous woman from South America. Several speakers came forward to reflect on the action. Faith Spotted Eagle—a Dakota woman who fought alongside thousands of others to defeat the KXL Pipeline, and has long worked with veterans suffering PTSD—came forward and invited onlookers to fight for Native women and also to recover from their own trauma, their own pain. Putting forward that to support our struggle you support your own.

Now is the time to start walking forward and never look back.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Google+

Google+ Tumblr

Tumblr Digg

Digg Reddit

Reddit StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon