The case for an independent Left party

If the 13.2 million votes received by self-styled “democratic socialist” Bernie Sanders in the 2016 Democratic presidential primaries accomplished nothing else positive, it put the questions of socialism and independent working-class politics up for public discussion. I have been critical of Sanders’s socialism because his policy platform was New Deal liberalism, not socialism. More importantly, by entering the Democratic Party, Sanders broke with the socialist principle of independent working-class political action.1 He became the “sheepdog” herding progressives, who had the option of voting for the Green ticket of Jill Stein and Ajamu Baraka in the general election, back into a party run by the billionaire class he professes to oppose.2 Nevertheless, the broad liberal to radical American left is now discussing what socialism is and debating whether the Left should be inside or outside the Democratic Party—or both inside and outside. These are good discussions to have.

As we enter the run-up to the 2018 midterm elections, Trumpism is weakening under its own self-inflicted wounds, the ambivalent legitimacy of Trump’s election by a popular minority due to the eccentricities of the Electoral College, and a spreading realization that behind the economic populism of his campaign rhetoric is the most reactionary Republican economic and social policy agenda since the late nineteenth-century era of Social Darwinism and Jim Crow. A massive resistance against Trump and his administration has emerged, and it is in the main counting on a Democratic restoration to save us. The Democrats may replace the irrationalities and racist revanchism of Trump, but they won’t replace the austerity capitalism and militaristic imperialism to which the Democratic Party is committed. It is a key institution upholding the broad policy consensus of America’s ruling class and its political representatives in the two-party system of corporate rule.

To avoid the political cul-de-sac of choosing between a greater and lesser evil, the Left must commit itself to building an independent, membership-based working-class party. Such a third-party insurgency in the United States must be built from the bottom up in two complementary ways. First, it must organize the working-class majority at the bottom of the social structure into a political party that speaks and acts independently for itself. Second, it must mobilize that base to participate in social movement and electoral activities to win and consolidate power and reforms first in cities, then states, and finally in the nation.

Will Ackerman’s party-within-the party work?

The Sanders wing of the resistance is debating whether to take over and reform the Democratic Party or lead reform Democrats out and into a new progressive party. Many in this camp advocate a so-called inside-outside strategy of supporting progressive Democrats or independents, depending on the dynamics of the particular race. The Working Families Party has pursued this approach since the 1990s, using the fusion tactic of running Democrats on their own ballot line as well as the Democratic line in the seven states where cross-endorsement is permitted.

Seth Ackerman’s “Blueprint for a New Party,” featured in the postelection issue of the socialist journal Jacobin, advocates a party-within-the-party model where a democratic, mass-membership organization would function as a political party—only without its own ballot line due to the obstacles thrown up by America’s close state regulation of parties, which serves to protect the two-party system. In Ackerman’s blueprint, the new working-class party would run its own candidates on Democratic, independent, or third-party ballot lines, depending on the race.3

The inside-outside and party-within-the-party approaches are nothing new.4 The failures of fusion go back to the political suicide of the People’s Party in 1896, when it cross-endorsed Democrat William Jennings Bryant for president. A succession of parties over eighty years in fusion-friendly New York—the American Labor Party, the Liberal Party, and the Working Families Party—have been co-opted into being adjuncts to the Democratic Party, not alternatives to it. The initially independent Vermont Progressive Party has embraced fusion with Democrats in recent elections and appears to be headed toward the same destination.5

The party-within-the-party approach has been tried in a variety of forms since the late 1930s by labor’s PACs (political action committees), waves of reform Democratic club networks, McGovern’s new politics, Michael Harrington’s Democratic Socialists of America, Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition, Howard Dean’s Democracy for America, Dennis Kucinich’s Progressive Democrats of America, Obama’s Organizing for America, and now Sanders’s Our Revolution. Over the course of these many efforts over many decades, the reformers have been defeated and co-opted, with the corporate New Democrats steadily displacing liberal New Deal Democrats.

The political dynamic of all inside-outside approaches leads increasingly inside in the Democratic Party. One must disavow outside options in order to be allowed inside Democratic committees, campaigns, primary ballots, and debates. Instead of changing the Democratic Party, the Democratic Party changes inside-outside activists. Careerism sets in. Many of the veterans of these inside-outside organizations who at one time talked of “realignment” of the parties to create an American Labor Party or Rainbow Party became Democratic operatives and politicians whose careers depend on loyalty to corporate Democrats.6

Sanders followed this logic from the start of his presidential campaign when he conceded—in order to be accepted onto primary ballots and into debates—that he would support the Democratic nominee and not run as an independent. He has continued further down this path since the election with his support for progressive candidates for Democratic Party offices in an effort to “transform the party” as well as for progressive Democratic candidates for public offices.7

Ackerman’s blueprint astutely criticizes most of these efforts, including Sanders’s Our Revolution, for being top-down nonprofits without accountability to an organized membership. But his blueprint still falls into the same trap of failing to establish the Left’s public identity as an alternative advocating socialist system change that is opposed to and independent of the pro-capitalist Democrats. By failing to act on its own and speak for itself in US elections since the late 1930s, the Left has disappeared from public view. It lost its voice and a platform from which to be heard.

Ackerman’s blueprint offers no answers for the inevitable practical pitfalls that his party-within-the-party, like previous inside-outside efforts, would face. When progressives lose Democratic primaries, the inside-outside groups must support the corporate Democrat as the lesser evil to the corporate Republican if they are to remain accepted inside the Democratic Party. When progressive Democrats win, they must caucus with corporate Democrats and muffle their criticisms of them in order to remain acceptable. They end up providing a progressive patina to the thoroughly capitalist Democrats they set out to change.

For an independent working-class party

So what would a socialist alternative to the capitalist Democrats look like, both as a program for social transformation and as a movement of the working class for its own freedom? Sanders’s regulatory and social insurance reforms of capitalism do not end the polarization of society into rich and poor flowing from the exploitation of working people. Those reforms do not end the oppression, alienation, and disempowerment of working people. Those reforms do not stop capitalism’s competitive drive for mindless growth that is devouring the environment and roasting the planet. Socialism as a program has traditionally meant economic democracy—social ownership of the means of production for democratic planning and allocation of economic surpluses—as a necessary condition for full political democracy and freedom. But in the absence of a sizable socialist Left that runs its own candidates against both capitalist parties, socialism has been reduced in popular parlance to simply government programs.8

An even more problematic confusion about socialism created by Sanders’s presentation of it is his abandonment of independent working-class politics. Socialists support most of the limited reforms Sanders advocates. Any competitive election campaign necessarily focuses on what policies a candidate can realistically advance in office, however much socialist candidates should take any good opportunity to expound upon the inherent problems of capitalism and present the full socialist alternative. If Sanders had not explicitly rejected social ownership of the means of production and instead had substituted the Scandinavian welfare states system for democratic socialism, his focus on immediate reforms in the heat of the campaign would have made his vision of socialism clearer.

But more than a program, socialism is the movement of the working class acting for itself, independently, for its own freedom. The socialist program that has historically been developed by that movement calls for full economic and political democracy as the institutional framework for full freedom. But when self-styled socialists like Sanders urge the working class to subsume its independent identity and political action inside a party that represents and serves business interests before all else, the working class surrenders its independent power, the socialist movement disappears as a distinct alternative, and working-class politics is reduced to begging and bargaining over the conditions of domination and exploitation rather than building the power to end those conditions.

The history of independent working-class parties

The independent Left was a force to be reckoned with in US politics from the 1830s through the 1930s. A succession of third parties—the Workingmen’s Parties, the Liberty Party, the Free Soil Party, and the Republicans—carried the causes of cooperative labor, abolition, land reform, and Radical Reconstruction from the 1830s through the 1870s. With post–Civil War industrialization and the capture of the Republicans by big business interests, the pre-war reform movements evolved into the populist farmer-labor Greenback Labor and People’s Parties of the 1880s and 1890s, which made their issues—monetary and banking reform, cooperatives, publicly-owned utilities, anti-monopoly measures, and voting rights—central election issues.

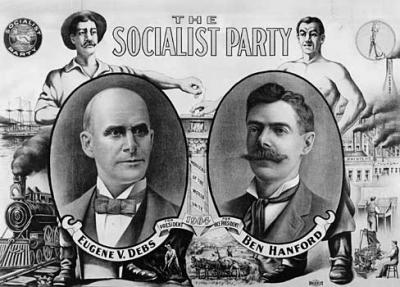

After the collapse of Populism into the Democratic Party, its radicals were central to the formation of the Socialist Party of America, as well as regionally based labor, farmer-labor, nonpartisan, and progressive parties between 1900 and 1936, which added social insurance, public jobs for the unemployed, and public enterprise in basic industries to the independent farmer-labor politics agenda. Together, these late nineteenth and early twentieth-century movements elected hundreds of local officials, scores of state officials, and dozens of members of Congress.

Those successes fueled widespread agitation for an independent labor party based on the unions, which reached a peak as the 1936 election approached. Unfortunately, the unions and the Communist Party’s Popular Front policy led most of labor and the Left into the Democratic Party’s New Deal Coalition in 1936. Labor and the broad progressive Left have remained captive to the Democratic Party ever since. Unlike almost every other industrial nation, the United States has yet to consolidate an independent working-class party as a major party.

What has made America a difficult terrain compared to other industrialized countries for developing a major working-class party is rooted in how its democratic forms initially developed.9 From the American Revolution and before, America’s landed and business elites supported a popular electoral franchise. Though initially extended only to propertied white males, political rights were articulated in universalistic terms, which other groups were able to appeal to in the course of American history to win the franchise for themselves.

In other industrially developing countries, workers and peasants had to form their own independent workers parties to fight for the voting franchise and social reforms against the new business elites as well as the old landed elites. That reality became the first principle of socialist politics: independent political action by the working class. Except for some socialist traditions in the ideological Left, independent politics has never taken hold as a principle in the popular Left in America.10 It has been particularly weak as a political principle since the unions and the Popular Front policy of the Communists in 1936 took the popular left as well as the majority of the ideological Left into the New Deal Coalition in the Democratic Party.

Most American progressives to this day regard the question of whether to run in the Democratic Party or independently as a tactical question to be decided according to immediate contingencies. If a third party based in the working class is ever to be formed in the United States, independent politics will have to be a principle, not a tactic to be picked up or discarded with each election cycle.11

The populist parties of the 1880s and 1890s and the Socialist Party of America and locally and regionally based labor, farmer-labor, nonpartisan, and progressive parties between 1900 and 1936 came close to establishing a major third party on the left with a working-class base. They demonstrated that independent working-class politics can overcome the structural barriers to a third party posed by single-member-district, winner-take-all elections, as have labor-based parties in similar electoral systems in other countries, including Canada, the UK, France, New Zealand, Mexico, and Venezuela. The failure to sustain independent labor parties in the United States can be found in their mimicking of the traditional American party structure developed by the Democratic and Republican parties instead of building a grassroots, mass-membership party funded by party member dues.

American capitalism’s memberless parties

If the Left in America is to challenge the capitalist two-party system, it will have to build a political party based on working-class independence from the corporate rulers and their political representatives in the Democratic and Republican Parties. To build that kind of party, it will have to build a mass-membership party that is structured quite differently from traditional American parties. Its members will have to be organized into local branches and finance their party with member dues, just as labor unions do, which is why unions have by far the most resources of any institution on the popular left. A dues-paying mass-membership party has been the missing ingredient in third-party politics throughout American history.

The history of third-party insurgencies on the left in American history teaches us that they have all floundered by structuring their parties on the traditional American party model, with the notable exception of the Socialist Party in the early twentieth century. In this structure, the representatives to the committees and conventions of the party are apportioned from jurisdictions according to the general population, the party registration, or the vote in a recent general election. Representatives in this structure are not elected by an active and organized party membership in those jurisdictions.

These parties don’t have members with rights and responsibilities in the party structure. This structure yields representation and control by party insiders who have no ongoing accountability to rank-and-file party supporters. The party insiders are the politicians and their paid staffs who sell themselves first to wealthy funders and then use those funds to sell themselves to voters.

American parties are not organized parties built around active members and policy platforms; they are shifting coalitions of entrepreneurial candidate campaign organizations. Hence, the Democratic and Republican Parties are not only capitalist ideologically; they are capitalistically run enterprises.

Parallel to the evolution of capitalism from competitive to monopolistic stages, the major party campaign committees have become monopolistic players in the candidate market in recent decades (on the Democratic side, the Democratic National Committee, the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee, the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee, and their state-level counterparts). They have been playing an ever-greater role in the selection and management of federal and state candidates using the flood of private money into party coffers that has swelled in concert with the growing concentration of wealth and income in the hands of the 1 percent since the 1970s.12

Party conventions were an American invention of the 1820s. But in the post-Civil War period they evolved from deliberative assemblies that met irregularly only as elections approached into patronage boss-controlled rituals. The membership was not organized into active local parties that engaged in regular meetings for education, debate, decisions, and actions. No active membership was organized to elect and hold accountable delegates to the higher councils of the party.

The primary system was instituted in the 1910s and was promoted by the progressive-era good government reformers to take the process of candidate selection out of the hands of the party bosses and put it back in the hands of the people. But because the people remained an atomized mass of unorganized party followers, the primary process was actually encouraged by the party bosses, who became the brokers of contributions from wealthy donors for candidate-based political operations, which progressively diminished the influence of the older patronage machines.13 Primaries became plebiscites on politicians who were effectively preselected by the wealthy funders of incumbent or aspiring politicians.

The Socialist Party: A precedent of a membership-based party

The Socialist Party (SP) is the only significant left third party in American history that was based on a dues-paying membership organized into local chapters, which was the norm for labor parties in the rest of the world. The mass-membership organization was the invention of the labor Left. It was absolutely necessary if working people were to have labor unions and political parties they controlled and with the resources needed for effective concerted action. It was the only way working people could compete politically with the old top-down elitist parties, which had evolved earlier out of legislative caucuses that were funded by rich sponsors and provided no formal structure for rank-and-file participation and accountable representation.14 The Democratic and Republican Parties retain these elite-serving top-down characteristics. It was the labor-based socialist parties that led the fight to extend the franchise to working people in countries around the world.15

The founders of the SP, many of them veteran populists, were well aware of the need for a mass-membership party structure that chose its platform and candidates at a yearly democratic membership convention. The socialists drew two organizational lessons from the demise of the People’s Party. First, they secured their political independence by banning fusion candidacies in the party constitution. Second, only dues-paying members were allowed to vote on party decisions in order to protect the Socialists’ internal democracy from being overwhelmed by the contemporary Progressive movement that might flood their meetings with different agendas and motivations like the shadow populist movement had done to the People’s Party.

The Socialists faced an additional barrier to organizing in their own way with the spread of primary elections, which took nominations out of the hands of party conventions and put it in the hands of a state-regulated party enrollment that was different from the active party membership. Direct primaries made American parties creatures of the state, rather than voluntary private associations. The state, not the party, set the conditions for “membership” by establishing the conditions for voting in party primaries.

These conditions vary from state to state depending whether or not the state keeps party enrollment lists and on the type of primary the state uses (open, closed, semi-open, top two, or blanket). But in all their variations, primaries tend to hand power to professional politicians sponsored by wealthy interests who can dominate an unorganized electorate in a top-down plebiscite. The Socialists maintained their membership convention system alongside the primary system. They nominated by convention and then campaigned for their nominees in primaries if necessary, nearly always winning those primaries.

Arthur Lipow explains that commentators at the time primaries were introduced foresaw the implications for democracy between party membership conventions and direct primaries.

In the United States, it was only in the internal structure of the Socialist Party that the democratic and representative type of party organization was developed. Writing in the middle of the Progressive period’s mania for “direct democracy” [i.e., primaries and referenda], the University of Chicago labor economist and historian Robert F. Hoxie pointed out that “it is a little known fact that the Socialists are introducing among us a new type of political organization and new political method very much in contrast with those to which through long usage we have become habituated.” He suggested that the democratically organized convention system represented “a political organization and political methods that are worth consideration on their merits as possible contributions to a more wholesome, more democratic, and more Progressive expression of the social will.”16

In a discussion of the spread of primary elections, the Socialist Call in 1914 denounced the progressives’ push for direct primaries: “In their eagerness to get the reputation for being democrats, those pseudo-democrats who are running things just now want to break up political parties. If they really wanted to have real democracy, they would pattern parties after our party.”17

The two-party duopoly ruling New York State would soon confirm the Socialists’ indictment of the memberless American parties. Ten Socialists were elected to the New York State Assembly in the 1918 election. But in the climate of the Red Scare and Palmer Raids against the antiwar Socialists following World War I, the New York State Assembly expelled the five socialists elected in 1920. A special election was called to replace them. Their districts reelected all of them. Again, they were not seated by the assembly.

To justify its actions, a special Joint Legislative Committee Investigating Seditious Activities soon issued a massive 4,428-page report on Revolutionary Radicalism: Its History, Purpose, and Tactics with an Exposition and Discussion of the Steps Being Taken and Required to Curb It. The long section on the Socialist Party of America begins:

The expression “Socialist Party of America” is really a misnomer, for the group operating under this name is not in reality a party. . . . The Socialist Party is in reality a membership organization. . . . A distinction must be drawn at this time between the members of the Socialist Party of America and the enrolled Socialists. . . . A person enrolling under the Socialist Party emblem on registration day in this state does not thereby become a member of the Socialist Party of America.18

In other words, for the memberless capitalist parties, it was subversive for the Socialist Party to be a membership organization. The last thing the capitalist parties wanted was for the working class to become well organized politically.

Although the progressive-era electoral reforms (direct primary, nonpartisan election, initiative and referendum) were nominally aimed at the corruption and boss control of urban patronage machines, they have been very effective in preventing the emergence of an independent left party in the contemporary period. Those growing out of the 1960s New Left such as the Peace and Freedom, People’s, and Citizens Parties did not organize as mass-membership parties. By contrast, the SP in 1973 and the Green Party USA in 1984 did form as dues-paying membership organizations.

However, both the Socialist and Green parties faced challenges to the mass-membership structure from state party affiliates that acquired ballot status in the 1990s. The state parties demanded more representation in their national committees and conventions based on their state-maintained party enrollment rather than their paid membership as provided for in the parties’ rules. In the case of the Green Party, the state-regulated party enrollment and primary system effectively disorganized and defunded the national party, leading to replacement by 2001 of affiliated locals of dues-paying members with a federation of state parties in a new Green Party of the United States that is organized around party committees peopled by party insiders who are self-selected, appointed from above, or (very rarely) elected at primaries, just like the Democratic and Republican parties.19 In the case of the Socialist Party, the challenging Oregon party soon lost its ballot line and later disaffiliated from the national party.

Uniting the working-class majority

Building a mass membership party is not only important for creating an accountable democratic structure that expresses the will of the membership. It is essential for unifying the working-class majority to take power. Local branches should serve as forums for political education where the disparate elements of the working class can find their common interests. The working class is segmented and mutually suspicious in contemporary society. A central mission of an independent left party must be to overcome that segmentation and unify the working-class majority politically.

American capitalism is divided up into three classes structured by its central organizing institution, the corporation. These are the ruling class (about 2 percent of the population), the middle classes (about one-third of the population), and the working classes (about two-thirds of the population). The corporate form and class structure extends from private businesses into government and nonprofit agencies, with their executive management at the top, professional staff and supervisory management in the middle, and workers at the base. The revolving door of executive management between the for-profit, nonprofit, and government sectors keeps the ruling class in charge in all three sectors.

The ruling class could not rule without the widespread political allegiance of most of the middle class. The middle class is a mix of a declining “old middle class” of self-employed and small business people and a growing “new middle class,” the professional, technical, and managerial employees embedded inside corporate structures. About ten million people are self-employed in their own small businesses on which they depend for most of their income. These small business owners are caught in the middle between big business and the working class. Unlike the Populist era when many small farmers and businesses tended to seek allies in the emerging working class against the banking and railroad establishment, today they tend to identify culturally and politically with the big businesses they hope to become.

The professional, technical, and managerial middle class in corporate society is comprised of supervisors, accountants, lawyers, engineers, technicians, doctors, nurses, college professors, and teachers, who by virtue of their specialized knowledge and skills have considerable autonomy and flexibility at work and supervisory authority over workers but who themselves are subject to supervision and discipline by top management in the corporate hierarchy. Some of these occupations are being increasingly pushed into the working class, particularly teachers with the advent of high-stakes testing; college professors with the proliferation of non-tenure, part-time, adjunct positions; and nurses and even doctors, who are increasingly subject to insurance company and hospital management decisions about what care will be paid for and for speedup of the patient-doctor encounter to increase “productivity.”

About twenty million work as professionals and, including their families, comprise about 20 percent of the population.20 Politically, they tend to be socially liberal, which is consistent with their professional standards and knowledge based in science and rationalism. But on the economic class issues, their allegiances are mixed. Some groups, notably teachers and nurses, tend to identify more with the working class as they fight to protect their independent professional expertise and judgment from encroaching corporate management.

Many others in the professional-managerial middle class tend to identify politically with the ruling class and support more conservative economic policies that are stingy on social spending for the services and benefits that workers use and favorable to policies that shift tax burdens to workers and benefits to the middle and upper classes. About half of all wage and salary income accrues to the middle-class elements of the corporate hierarchy, which makes their incomes on average more than double the income of workers and growing relative to workers.21 With workers widely alienated from the political process and voting at low levels, the middle class has been the mass voting base for the conservative economic policies of the two major parties.22

The working class is comprised of those who work as directed by supervisory management with little to no autonomy, flexibility, or authority on the job. Using this definition, Michael Zweig in The Working Class Majority put the American working class at 96.7 million people, or 63 percent of 152.7 million people in the workforce in 2010. That left 55.9 million people drawing wages and salaries in the middle and upper classes. US Department of Labor statistics put “non-supervisory” workers at 82 percent of the workforce, although that included professionals with considerable job autonomy who are not in supervisory management.23 For our purposes here, the exact numbers are not as important as noting that workers are the majority and the middle classes provide the mass voting base for the two corporate parties.

The working class may be the majority, but it is divided into four segments that tend to see each other as competitors, not allies: (1) mostly non-union, competitive sector, small business workers; (2) sometimes unionized, oligopolistic sector, corporate workers; (3) often unionized, public sector workers; and (4) workers under state supervision in the welfare and correctional systems.24

Crossing all these segments of the working class are racial and ethnic divisions that have divided the American working class throughout its history. About 35 percent of the working class is Black, Asian, or Hispanic compared to 22 percent of the middle class.25 While people of color make up 30 percent of the US population, they account for 60 percent of those imprisoned.26 School segregation by income as well as race has been growing since the 1980s and now comparable to what obtained when Brown v. Board of Education struck down school segregation laws.27 Residential segregation is greater today than it was in 1940 and unchanged since 1950.28 Racial exclusion and discrimination within progressive movements has been the Achilles’ heel that divided and undermined the potential strength of every working-class and progressive reform movement so far in American history.29

All these segments of the working class share the experience of being directed by others at work or in the welfare and correctional systems. They all do not enjoy the full fruits of their labor, the surplus of which above their wage is appropriated by business owners as profits and higher salaries for top management and the professional-managerial middle class. They share a common interest in pursuing public policies that ensure economic human rights to decent employment, living wages, health care, quality education, affordable housing and transit, and a clean and sustainable environment. They share a common interest in more progressive taxes and a more equitable allocation of public spending on schools and services. They share a common interest in democratizing economic decision-making and the disposition of economic surpluses so that all can enjoy the full fruits of their labor and all can participate in the planning, management, technology choice, and other economic decisions that affect their lives.

With the working class divided into separate occupational and racial silos, an independent left party must organize across these divisions to bring different segments of the working class into accessible, local public forums where people can talk about their problems and develop their ideas for resolving them. In the course of that self-education process, working people can find their common interests and break down the myths, suspicions, and resentments that divide them.

In the absence of such a party, the divided working class sees other segments as competitors for scarce job, education, and housing opportunities. The racial dimension of this competition is long standing and well known. But any observer of the political narratives of right-wing radio, the corporate mass media, and major party politicians can see how the competitive, corporate, public, and administered sectors of the working class are encouraged to see each other as competitors rather than allies on such issues as schools, taxes, pensions, and welfare. An independent left party will have to find ways to break through these resentments if it is to organize a voting base that can elect its candidates to office.

Bottom-up organizing, not top-down mobilizing

A mass party that organizes working people into local parties that provide a forum for political discussion and decisions about policy positions and actions is crucial to building the sense of empowerment and self-confidence that working people need to take on the entrenched political powers. The ruling-class/middle-class political alliance prevails in elections because working people vote in such low numbers. Many attribute this to apathy.

But in my experience talking to working-class people in political campaigns for more than four decades and in running for office many times in the last two decades, that apathy is rooted in alienation from the political elites and demoralization at the slim prospects of making changes against their perceived overwhelming power. Many working people feel the politicians of both parties have no idea what their lives are like and what their issues really are. They feel invisible to the politicians. Many just stop paying attention to politics because it is so painful to feel they can’t make any difference. They believe the politicians are going to do what they want to do and voting won’t make any difference.

The campaign strategies of the major parties reinforce low turnout by working-class communities. During elections, campaigns target middle-class voters and precincts with histories of high voter turnout and neglect working-class voters and precincts with low voter turnout as a waste of limited campaign resources. Between elections, they make no effort to engage the low turnout voters.

An independent party of the Left can build its base by filling this political vacuum and engaging working-class people who are now disaffected from and neglected by the political process. It needs to engage them between as well as during elections. Crucially important in organizing from the bottom up, an independent left party must prioritize organizing Black people, Latinx, and other people of color. If not centrally involved, their particular concerns tend to be neglected. If not involved from the beginning of organizing, the barriers to later inclusion are difficult to overcome given the existing patterns of residential and social segregation and the long historical legacy of racism that yields suspicion and skepticism when a majority white organization attempts belatedly to include people of color. With more than a third of the American working class comprised of people of color, a working-class party that is not well-rooted in working-class communities of color and championing their demands has failed to organize the whole class and will not realize its potential electoral majority.

The labor movement also tends to reproduce the corporate class structure. Some unions do practice a social movement unionism that engages their members in education and decision-making and seeks to build a class-wide movement with labor and community allies. But most unions practice a transactional business unionism where the officers and top staff make the decisions and cut the deals and the members’ role is minimized.30 With automatic dues deductions administered by the payroll systems of employers, most unions’ top leaders control a budget and make decisions with little participation from the membership. The professional-managerial staff tends to be college graduates, sometimes of labor studies departments, who mobilize the working-class membership for elections and sometimes demonstrations when the union wants to lobby for a bill or put pressure on an employer during contract negotiations.

Few unions organize their members for political education and lateral communications. The union bureaucracy tends to worry that an organized membership would vote them out of office. Incumbent politicians, especially Democrats, receive union endorsements and donations for election campaigns, not because they are great champions of labor’s cause, but because union leaders want access to the politicians in power.31 So union decisions, like nonprofit advocacy decisions, tend to be made from the top down. As Arun Gupta reported on the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) Fight for 15 campaign,

There’s little evidence of worker-to-worker organizing. . . . Victor (not his real name) in Seattle says the campaign is faltering because workers are “babied at the meetings.” He says the process involves workers getting “amped-up” and “rubber-stamping some decisions that are already made,” which wears thin after the first meeting.32

Bottom-up organizing, as opposed to top-down mobilizing, means assisting working people to come together to make their own decisions. An exemplary case of this kind of organizing was how the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) organized the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) in 1964. Led by well-educated students and teachers like the Harvard-educated mathematician Bob Moses, SNCC’s main organizer of Freedom Summer in Mississippi, the SNCC organizers did not put themselves into leadership positions in the MFDP. They organized Freedom Schools to provide both basic and political education to the sharecroppers, small farmers, and farm and factory laborers they were organizing. They let these people choose their own leaders.

When the integrated MFDP delegation challenged the segregated Mississippi Dixiecrat delegation for seating at the National Democratic Convention, it was a sharecropper Fannie Lou Hamer who was elected as a cochair to speak for the delegation. President Johnson sent three prominent liberals—Minnesota senator Hubert Humphrey, Minnesota attorney general Walter Mondale, and United Auto Workers president Walter Reuther—to offer the MFDP a compromise of two non-voting at-large seats on the convention floor. The middle-class leaders of the mainstream civil rights and liberal organizations, including Martin Luther King Jr., at first urged the MFDP to take the compromise as progress.

But Fannie Lou Hamer said, “We didn’t come all this way for no two seats,” and persuaded the MFDP delegation to vote to reject the compromise as tokenism.33 That is what happens when working people are organized to speak for themselves and elect their leaders. Those leaders have little to gain from selling out for token symbolic measures. They will be ostracized by their organized peers if they do so. Middle-class leaders, on the other hand, do have something to lose. Their careers are at risk if they buck the system that pays them. They tend to be more willing to compromise workers’ interests.

What the SNCC organizers did with the MFDP is what the socialist left has long advised: build an independent party of working people and they will take care of the policy program in time. When the Independent Labor Party on New York, created by 175 labor unions in New York City, nominated the non-socialist reformer Henry George as its mayoral candidate in 1886, Frederick Engels advised the Socialist Labor Party in America to support the campaign and participate in the Independent Labor Party despite his misgivings about George’s platform:

In a country that has newly entered the movement, the first really crucial step is the formation by the workers of an independent political party, no matter how, so long as it is distinguishable as a labor party. . . . That the first program of this party is still muddle-headed and extremely inadequate, that it should have picked Henry George as its figurehead, are unavoidable if merely transitory evils. The masses must have time and opportunity to evolve, and they will not get that opportunity until they have their own movement—no matter in what form so long as it is only their own movement—in which they are impelled onwards by their own mistakes and learn by bitter experience.34

For both the nineteenth-century socialists and the MFDP, the party and the movement went together. For the socialists, participating in the labor movement, organizing unions, fighting for better wages and working conditions on the job were a central part of the party’s work. Similarly, SNCC did not organize the MFDP in a vacuum. It was built at the same time in 1964 that forty-one Freedom Schools taught an academic curriculum focused on reading, writing, math, and basic science and a citizenship curriculum focused on Black history, power structure analysis, and movement history.35 In 1965, they organized the Mississippi Freedom Labor Union among day laborers and domestic workers.36

The notion that the party should focus on electoral work and leave movement work to others prevents the party from engaging working people between as well as during elections. It is essential that the party not leave educational and social movement projects to the corporate structures of the foundation-funded nonprofit advocacy and business unionism. The nonprofit advocacy groups and business unions rarely offer a platform to independent left activists for fear of losing access to Democratic funders and politicians. They just want the independent left to show up at events in order to increase attendance without giving them any voice in them. Their strategies are oriented to lobbying the Democrats, not exerting independent power that, while it may move Democrats on issues, has the strategic goal of replacing corporate Democrats with third-party insurgents.

Building electoral power from the bottom up

If an independent left party can only be organized from the bottom up, it can also only build power in elections from the bottom up, focusing on local elections to establish a base for later effective forays into state and national level elections.

Most local elections are on a small enough scale that a grassroots door-to-door campaign can reach the voters without a large budget for direct mail and paid advertising. Broadcast advertising is often an irrelevant waste of money because most viewers and listeners will not reside in the district covered. Many incumbents run unopposed in local elections because most districts are one-party districts in our winner-take-all system and the major party that is the minority in a district often does not run a candidate. That means a third-party candidate will often be the second candidate in a local election, eliminating the incentives for lesser evil voting in a three-candidate race in a winner-take-all election.

In the absence of a commitment to independent working-class politics as a principle on the American left, it is not surprising to see the drift away from independent politics by the Vermont Progressive Party and the Richmond Progressive Alliance. Their electoral coalitions with Democrats is consistent with the majority of post-1960s New Left progressive electoral activity, which has mostly been directed through the Democratic Party.37 These efforts have won some local reforms but have failed to move the national Democratic Party to the left. To the contrary, since the 1960s, the national Democratic Party has replaced the leadership of liberal New Deal Democrats with the leadership of corporate New Democrats. The national Democratic Party can tolerate a few liberal local bases like San Francisco, Minneapolis, and New York, and even use them as examples to lure progressives back into what remains a conservative pro-corporate political party at the top.

With over 39,000 municipal governments, nearly 13,000 independent school districts, and over 500,000 elected positions in those governments, there is no shortage of opportunities for an independent left party to run candidates. Indeed, a significant proportion of local officeholders are reelected with no opposition. The typical situation is that the local elite, usually embedded in the real estate and development industry, runs these municipal governments in a self-serving, if not outright corrupt, fashion. They hold on to power because local governments within the federalism of the American political system have real powers.

Few local governments around the world have the autonomy and powers of America’s municipal governments to tax, borrow, spend, invest, contract, purchase, hire, zone, regulate, lobby, police, amend their charters, start businesses as public enterprises, and even expropriate private property for public purposes through the power of eminent domain. These powers provide plenty of scope for an independent left party to advance its program.

As an independent left party takes power in localities and demonstrates its competence to the public, the door opens for winnable races at the state and federal level. District races for state legislatures and the US House of Representatives are local races, the next step up from municipal district and at-large races. While money for advertising and direct mail plays a far bigger role than in most municipal elections, a well-organized third party can compensate with a strong field operation for direct voter contact. A longtime advocate for a bottom-up strategy, Gar Alperovitz, has called this the “checkerboard strategy.”38

The conditions are ripe

I have focused here on the subjective side—what third-party organizers can do to build up an independent left party into a major party. But it is also worth noting that the objective conditions for a working-class major party have grown stronger over the past century. First, the working-class majority is built into the class structure of corporate society. It has grown from about a third of the population in 1900 to about two-thirds of the population today as the corporate form of property ownership and social organization has come to pervade society.

Second, sizable sections of the middle class hold progressive values and are open to allying politically with a working-class party as opposed to the more liberal Democrats in the ruling two-party duopoly. These sections include many in the “helping professions” (teachers, social workers, nurses) and many in the scientific and legal professions (scientists, engineers, technicians, doctors, lawyers). These sectors have been predominant base of the new Green parties around the world. Many in these professions reject the growing constraints on their professional autonomy imposed by corporate hierarchies.

This subjection to corporate hierarchies is becoming more like that experienced by the working class. It has led some to propose that these well-educated middle-class people constitute a “new working class.” That thesis probably overstates the similarities in working conditions with the working class proper. However, their high levels of education predispose them to an optimistic problem-solving rationalism that is characteristic of political progressives as opposed to the pessimistic better-left-alone traditionalism of political conservatives. By winning over a sizable segment of middle-class voters, a working-class party can reduce the biggest voting bloc of support for the corporate elite’s two major parties.

Third, the working class is better educated than ever. It is more inclined to consider reason and evidence than to take things on faith from religious or political leaders. It is therefore more capable than ever of participating in democratic self-rule. This growing education and rationalism also undergirds the steady growth for decades of more egalitarian attitudes in support of racial, women’s, and LGBT equality. The recent rapid transformation of public opinion from small minority to growing majority in support of gay marriage in less than a decade indicates this trend may be accelerating. These attitudes are strongest in younger cohorts. This bodes well for the prospects of unifying the working class politically across race, gender, and occupational lines.

Fourth, working-class living standards have declined over the last forty years. Hourly wages for workers are slightly below what they were at their peak in 1973. In attempting to maintain living standards, the working class is buried in record levels of debt. The younger cohorts of the working class face downward mobility due to difficulty finding decent-paying jobs and a record level of student loan debt. Over these same decades, the Democratic Party that by self-description looks out for the working people has failed when in power to reverse the declining fortunes of the working class. An independent working-class party can step into the political void left by these circumstances.

Fifth, the urgency of environmental crisis, particularly the climate crisis, requires a break with politics as usual. Society must make a decisive turn toward rapidly reducing fossil fuels and ramping up clean renewables if it is to avoid radical climate change that will precipitate mass extinctions, food shortages, mass migrations of environmental refugees, and wars for scarce resources. While opinion polls show that voters across the class structure still prioritize environmental and climate action below bread-and-butter economic issues and some social and foreign policy issues, they also show that strong majorities want action on climate and the environment.

The failure of the corporate parties to address these economic and environmental problems has led to a growing alienation from both major parties. The Pew Research Center’s tracking of party identification shows poll found that Americans calling themselves political independents has been trending upward and is higher than at any time in the last seventy-five years. Independents at 40 percent outnumbered Democrats at 30 percent and Republicans at 24 percent in 2015.39 Pew found that 48 percent of millennials ages eighteen to thirty-three considered themselves political independents in 2015. A 2013 Gallup poll found that a record 60 percent of Americans believe the Republicans and Democrats “do such a poor job of representing the American people that a third major party is needed.” Only 26 percent said that, “the Republican and Democratic parties do an adequate job representing the American people.”40

The working-class majority is far more progressive, especially on economic class issues, than the media pundits, the middle-class leadership of advocacy groups and the business unions, and the Democratic leadership would have one believe. These quarters repeatedly claim that popular reforms are politically impossible. However, a recent survey of the policy preferences of the wealthiest 1 percent compared to the general population revealed a huge gap between what the elite wants and what the people want. Among the results41:

Top 1%

Bottom 99%

Increase Social Security benefits

34%

73%

Minimum wage above poverty line

40%

78%

Government should ensure full employment

19%

68%

Publicly financed national health insurance

32%

61%

Federal spending sufficient for good schools for all

35%

87%

Federal spending to ensure all can go to college

28%

78%

This disjunction between popular preferences and elite policy-making helps explain what happened in the 2016 presidential election, when a largely progressive-minded working class stayed home and a smaller minority voted third party in much larger numbers than voted for Trump. The overwhelmingly Democratic Black and Latinx vote was down for Clinton compared to Obama. Contrary to popular myth, white working-class Democratic-leaning voters didn’t flip to Trump in large numbers. Of those who abandoned Clinton, twice as many voted third party or stayed home than voted for Trump. It was white middle-class Democrats who moved in large numbers to Trump.42

A fundamental problem with American politics is that popular preferences are not converted into public policy. A 2014 study examined 1,779 national policies enacted between 1981 and 2002 in the United States. It compared the policies enacted to the expressed preferences of average Americans (fiftieth percentile of income), affluent Americans (ninetieth percentile), and large special interests groups. The study concluded that the United States is ruled by its economic elites. “When a majority of citizens disagrees with economic elites and/or with organized interests, they generally lose. Moreover, because of the strong status quo bias built into the US political system, even when fairly large majorities of Americans favor policy change, they generally do not get it,” the study concluded.43

The policy outcomes in the study covered both Republican and Democratic administrations. Both corporate parties respond more to the economic elites that invest in them than in the people who vote for them. This leaves a political vacuum that an independent working-class party could fill—from the bottom up. And we need to build a socialist left that is clear-eyed about the necessity of that task.

- Howie Hawkins, “Bernie Sanders Is No Eugene Debs,” Socialist Worker, May 26, 2015, https://socialistworker.org/2015/05/26/b....

- Bruce A. Dixon, “Presidential Candidate Bernie Sanders: Sheepdogging for Hillary and the Democrats in 2016,” Black Agenda Report, May 6, 2016, https://www.blackagendareport.com/bernie....

- Seth Ackerman, “Blueprint for a New Party,” Jacobin, November 8, 2016, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2016/11/berni....

- Howie Hawkins, “Safe States, Inside-Outside, and Other Liberal Illusions,” CounterPunch, May 10, 2016, http://www.counterpunch.org/2016/05/10/s... Howie Hawkins, “An ‘Inside/Outside’ Strategy or Independent Politics,” New Politics (Summer 1989), No. 7, Vol II.

- Ashley Smith, “Vermont’s Cautionary Tale,” Jacobin, August 24, 2016, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2016/08/vermont-progressives-vpp-sanders-democrats-independent/.

- Kim Moody, “From Realignment to Reinforcement,” Jacobin, January 26, 2017, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2017/01/democ....

- Our Revolution’s website has a “Transform the Party” section, which explains, “We are transforming the Democratic Party from the ground up. Precinct by precinct, and county by county, all across the country (and the world!), progressives have stepped up to run for positions of leadership in their Democratic Party—and those have added up to hyooooge wins in creating a people-powered party,” http://transformtheparty.com/.

- Chris Maisano, “Isn’t America Already Kind of Socialist?” Jacobin, January 1, 2016, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2016/01/democratic-socialism-government-bernie-sanders-primary-president/.

- The outline that follows here of the historical obstacles to consolidating a working-class party in US politics draws on the detailed examinations of this issue in John McDermott, The Crisis of the Working Class and Some Arguments for a New Labor Movement (Boston: South End Press, 1980) and Mike Davis, Prisoners of the American Dream: Politics and Economy in the History of the US Working Class (London: Verso, 1986).

- Stanley Aronowitz introduced this useful distinction between the “ideological left” of socialists, communists, and anarchists and the “popular left” of labor, farmer, consumer, civil rights, peace, and environmental movements in “Remaking the American Left, Part One: Currents in American Radicalism,” Socialist Review, 63, January–February 1983.

- See Eric Thomas Chester, Socialists and the Ballot Box: A Historical Analysis (New York: Praeger, 1985).

- Moody, “From Realignment to Reinforcement.”

- Alan Ware, The American Direct Primary: Party Institutionalization and Transformation in the North (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002).

- Maurice Duverger, Political Parties: Their Organization and Activities in the Modern State (New York: Wiley, 1966).

- Dietrich Rueschemeyer, Evelyne Huber Stephens, and John D. Stephens, Capitalist Development and Democracy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992); Geoff Eley, Forging Democracy, The History of the Left in Europe, 1850–2000 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002).

- Arthur Lipow, Political Parties and Democracy (London: Pluto Press, 1996), 22.

- Lipow, Political Parties and Democracy, 17.

- Report of the Joint Legislative Committee Investigating Seditious Activities, Revolutionary Radicalism: Its History, Purpose, and Tactics with an Exposition and Discussion of the Steps Being Taken and Required to Curb It (Albany: New York State Senate, April 24, 1920), 510. This 4,428-page document covers socialist, communist, anarchist, and syndicalist movements around the world in the wake of the Russian Revolution. The section on the Socialist Party of America beginning on page 510 provides much detail on the party’s structure, rules, and policies. The document is online at https://books.google.com/books?id=CujYAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA3&lpg=PA3&dq=nys+assembly+judiciary+committee”https://books.google.com/books?id=CujYAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA3&lpg=PA3&dq=nys+assembly+judiciary+committee.

- For my take as a participant in the Green Party debates over structure, see Howie Hawkins, ed., Independent Politics: The Green Party Strategy Debate (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2006), 24–25.

- Michael Zweig, The Working Class Majority: America’s Best Kept Secret, 2nd ed. (Ithaca, NY: Cornel University Press, 2012), 30.

- John McDermott, Corporate Society: Class, Property, and Contemporary Capitalism (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1991), 135; Stephen J. Rose, “Trump and the Revolt of the White Middle Class,” Washington Monthly, January 18, 2017, http://washingtonmonthly.com/2017/01/18/....

- Frances Fox Piven and Richard A. Cloward, Why Americans Don’t Vote (New York: Pantheon Books, 1988).

- Zweig, Working-Class Majority, 31.

- This discussion of four segments of the American working class draws on McDermott’s Crisis of the Working Class and Corporate Society.

- Zweig, The Working Class Majority, 33.

- Prison Policy Project, “Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2017,” March 14, 2017, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/pie....

- Gary Orfield et al., Brown at 60: Great Progress, a Long Retreat and an Uncertain Future UCLA Civil Rights Project, May 15, 2014, http://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/integration-and-diversity/brown-at-60-great-progress-a-long-retreat-and-an-uncertain-future/.

- Richard Rothstein, Racial Segregation Continues, and Even Intensifies, Economic Policy Institute, February 3, 2012, http://www.epi.org/publication/racial-segregation-continues-intensifies/.

- Robert L. Allen, Reluctant Reformers: Racism and Social Reform Movements in the United States (Washington DC: Howard University Press, 1983).

- Kim Moody, An Injury to All: The Decline of American Unionism (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 1988), 58–65.

- Kim Moody, US Labor in Trouble and Transition: The Failure of Reform from Above, the Promise of Revival from Below (London: Verso, 2007).

- Arun Gupta, “Fight for 15 Confidential,” In These Times, November 11, 2013, http://inthesetimes.com/article/15826/fight_for_15_confidential”http://inthesetimes.com/article/15826/fight_for_15_confidential.

- Lani Guinier, “No Two Seats: The Elusive Quest for Political Equality,” Virginia Law Review 77 (November 8, 1991): 1413.

- Frederick Engels to Friedrich Adolph Sorge, November 29, 1886, in Karl Marx, Frederick Engels: Collected Works, Volume 47 (New York: International Publishers, 1995), 532.

- Freedom School Curriculum Website, http://www.educationanddemocracy.org/ED_FSC.html”http://www.educationanddemocracy.org/ED_FSC.html.

- Clayborne Carson, In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995), 172.

- Eric Leif Davin, Radicals in Power: The New Left Experience in Office (New York: Lexington Books, 2012).

- Gar Alperovitz, “A Checkerboard Strategy for Regaining the Progressive Initiative,” Truthout, December 20, 2012, http://truth-out.org/opinion/item/13592-....

- Pew Research Center, “A Deep Dive into Party Affiliation,” April 7, 2015, http://www.people-press.org/2015/04/07/a-deep-dive-into-party-affiliation/.

- Jeffrey M. Jones, “In U.S., Perceived Need for Third Party Reaches New High,” Gallup Politics, October 11, 2013, http://www.gallup.com/poll/165392/perceived-need-third-party-reaches-new-high.aspx.

- Benjamin I. Page, Larry M. Bartels, and Jason Seawright, “Democracy and the Policy Preferences of Wealth Americans,” Perspectives in Politics 11 (March 1, 2013).

- Konstantin Kilibarda and Daria Roithmayr, “The Myth of the Rust Belt Revolt: Donald Trump Didn’t Flip Working-Class White Voters; Hillary Clinton Lost Them,” Slate, December 1, 2016, http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_p... Kim Moody, “Who Put Trump in the White House?” Against the Current, January–February 2017, https://www.solidarity-us.org/site/node/... Mike Davis, “The Great God Trump and the White Working Class,” Jacobin, February 2017, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2017/02/the-g... Charlie Post, “The Roots of Trumpism,” Left Voice, December 16, 2016, http://www.leftvoice.org/The-Roots-of-Tr... Jesse A. Myerson, “Trumpism: It’s Coming from the Suburbs - Racism, Fascism, and Working-Class Americans,” Nation, May 8, 2017, https://www.thenation.com/article/trumpism-its-coming-from-the-suburbs/.

- Martin Gilens and Benjamin I. Page, “Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens,” Perspectives in Politics, Fall 2014, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/....

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Google+

Google+ Tumblr

Tumblr Digg

Digg Reddit

Reddit StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon