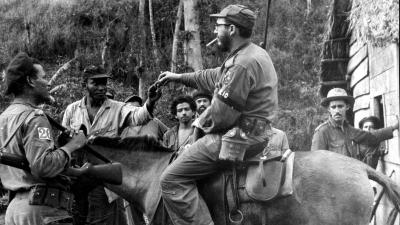

Fidel Castro

Cuba has not been at the center of world attention for a long time, particularly after the collapse of the Soviet bloc considerably diminished the island’s importance to US imperialism. For the international left, political developments in other Latin American countries, especially Venezuela, have surpassed Cuba as a primary focus of attention. That does not mean, however, that the Cuban model has ceased to be a desirable, even if at present unrealizable, model for significant sections of the left, particularly in Latin America. For larger sections of the left, there is still considerable misinformation and confusion about the true nature of Cuba’s “really existing socialism,” a confusion that far from being of merely academic interest has a significant impact on the left’s conception of socialism and democracy. The lack of democracy and therefore of authentic socialism in Cuba is not only a problem of interest to Cubans, but also a critical test of how seriously the international left takes its democratic pronouncements.

Origins

The Cuban Revolution was an unexpected and welcome surprise to many. After the rebel army, supported by an important urban underground, smashed Cuba’s regular army, what began as a political revolution quickly became a social revolution, the third in Latin America—after those of Mexico in 1910 and Bolivia in 1952. For the anti-imperialist left in Latin America and elsewhere, it represented a successful defeat and comeuppance of the US empire, which had recently frustrated the Bolivian revolution and overthrown the reform movement of the democratically elected Jacobo Árbenz in Guatemala in 1954.

The Cuba of the 1950s shared many traits with the rest of Latin America: economic underdevelopment, poverty, subjection to US imperialism, and after the military coup of March 10, 1952, a corrupt military dictatorship that became increasingly brutal as resistance to it increased. Military dictatorships were particularly common in Latin America at the height of the Cold War when they enjoyed the full support of Washington in the name of opposing “Communist subversion” in the region. Besides General Fulgencio Batista’s Cuba, this was also true for such dictatorships as those in Venezuela, Colombia, Paraguay, Perú, Nicaragua, and the Dominican Republic.

Yet Cuba was the only one among this group of nations that had a successful multiclass democratic revolution that less than two years after having taken power was well on its way to joining the Communist1 bloc of countries led by the USSR, right in the backyard of the United States. This dramatic change plus the social gains that were made by the Cuban people in education, health, and other social-justice issues, particularly in the early decades of the revolution, elicited the support of the old and new generations of anti-imperialist women and men.

What made that revolution possible? An answer to this question requires a discussion, on one hand, of the social structural conditions that facilitated a revolution, and on the other hand, of the political figures, particularly Fidel Castro, who harnessed those conditions to implement their own revolutionary goals. This particular combination of social structural conditions and political leadership also explains the overwhelming power that Fidel Castro was able to obtain as a revolutionary head of state.

On the eve of the revolution:Combined and uneven development

The Cuba of the 1950s occupied a relatively high economic position in Latin America. With a population of 5.8 million people, the island had the fourth highest per capita income among the twenty Latin American countries after Argentina, Uruguay, and Venezuela, and the thirty-first highest in the world.2 Cuba also ranked fourth in Latin America according to an average of twelve indexes covering such items as percentage of the labor force employed in mining, manufacturing, and construction; percentage of literate persons; and per capita electric power, newsprint, and caloric food consumption.3 Yet, its economy was characterized by a highly uneven and combined development. Its relatively high economic position in Latin America hid substantial differences in living standards between the urban (57 percent of Cuba’s population in 1953), and rural areas (43 percent), and especially between the capital city, Havana (21 percent of Cuba’s population) and the rest of the country. Thus, for example, 60 percent of physicians, 62 percent of dentists, and 80 percent of hospital beds were in Havana,4 and while the rate for illiteracy for the country as a whole was 23.6 percent, the rate for Havana was only 7.5 percent in contrast to 43 percent of the rural population that could not read or write.5

One important feature of this uneven economic development was the significant growth and advance of the mass media, which turned out to play an important role in the revolution. These included newspapers, magazines, radio, and particularly television, of which Cuba was a pioneer in Latin America.6 The largest weekly magazine Bohemia—with its left of center politics—counted its circulation in the hundreds of thousands, including its significant Latin American export audience. Bohemia published many of Fidel Castro’s exhortations to revolution during those periods when there was no censorship under the Batista dictatorship. After the revolutionary victory, television became an important vehicle for Fidel Castro’s interviews and speeches oriented to win over and consolidate support for the revolutionary government. Contrary to the African American poet and singer Gil Scott-Heron’s 1971 prophecy, this revolution was televised.

No oligarchy

Perhaps the most politically important distinguishing feature of Cuba’s social structure in the 1950s is that it lacked an oligarchy, that is the close organic relations among the upper classes, the high ranks of the armed forces, and the Catholic Church hierarchy, which had effectively acted as the institutional bases of reaction in many Latin American countries. In 1902, with the formal declaration of Cuban independence from the US occupation that had replaced Spanish colonialism in 1898, a half-baked and fragile Cuban oligarchy came into being, represented by the classic duopoly of the Liberal and Conservative parties that relied on the support of a weak, sugar-centered bourgeoisie devoid of a national project. At the same time, a class of predominantly white army officers—many of whom had served as generals in the Cuban war of independence in the 1890s—with organic ties to the Cuban upper classes, ran the army.

As in the rest of the Spanish-speaking Caribbean, the Catholic hierarchy, while influential, was not then, nor later, a major and decisive political actor, in contrast with the more crucial role it played in many other Latin American countries. One of the main causes of the weakness of this oligarchy was the sharp limits on Cuban independence established by the United States through the Platt Amendment imposed on the Cuban Constitution of 1901 granting the United States the legal right to intervene in Cuban affairs, which the Cubans were forced to accept as a condition of the “independence” of the island.

This half-baked oligarchic arrangement came crashing down with the 1933 revolution that succeeded in overthrowing the Machado dictatorship and established for a short time a nationalist government—strongly supported by the popular classes—that introduced labor and social legislation, and with it the foundations of a Cuban welfare state.7 The US government refused to recognize this government, which was soon overthrown with US support by the new plebeian army leadership of sergeants led by Fulgencio Batista who eliminated the old officer class. After the overthrow of the progressive nationalist government, the United States, in an attempt to provide some legitimacy to the unpopular government controlled by the former sergeant now turned Colonel Batista, agreed in 1934 to abolish the Platt Amendment. In return for a greater degree of political self-rule, Batista accepted, in addition to concessions such as maintaining the US naval base at Guantánamo Bay, a new reciprocity treaty that perpetuated the reign of sugar, thereby hindering attempts to diversify the economy of the island through which other Latin American countries, such as Mexico, had achieved some success with their import substitution policies.

This is how the 1933 revolution produced no permanent resolution of any of the major social questions affecting the island, including badly needed agrarian reform, and led instead to open counterrevolution and then, under the contradictory pressures of US capital and the world market on one hand, and of the ever-present threat of working class and popular unrest on the other hand, to a variety of state-capitalist compromises involving the significant state regulation of the economy that discouraged foreign investment. The most important example was the case of the sugar industry where the state established, in 1937, a corporate entity to oversee the industry (Instituto Cubano de Estabilización del Azúcar—ICEA) and a detailed set of regulations of labor conditions, wages, and production quotas for the industry as a whole as well as for each sugar mill. These were the kinds of institutional arrangements that framed the social and political modus vivendi of the next two decades of Cuban history.

No major social class emerged totally victorious after the 1933 revolution, and although capitalism and imperialism strongly consolidated themselves, a capitalist ruling class of equal strength did not, in part because of its reliance on the US as the ultimate guarantor of its fate against any possible internal threat to its power and privileges. Instead, there was a numerically important Cuban business class that did not really rule but bolstered its privileged position and benefited as much as it could from the governments of the day. This Cuban business class initially supported the Batista dictatorship in a purely opportunistic fashion, but later abandoned it as the very corrupt government shook down businesspeople without even being able to guarantee law and order and a predictable legal and business climate. This helps to explain why prominent members of the business class, such as the very wealthy sugar magnate Julio Lobo, helped to finance Fidel Castro’s 26th of July Movement before it came to power.8

The Batista sergeants’ coup also led to the emergence of a new army headed by the former sergeants suddenly turned into colonels and generals, who never recognized or ceded their control to the newly trained professional officers schooled in the island’s military academies, to serve the Constitution in a nonpartisan manner. Instead, the Cuban army remained a fundamentally political, mercenary army whose rank-and-file members served on a voluntary basis in exchange for a secure job and salary, devoid of any purpose or ideology except for the personal enrichment of its leaders and the meager benefits that trickled down to its ranks.9 This explains the failure of the attempt by the academy-trained professional military officers—the so-called puros (the pure)—to overthrow the Batista regime in 1956 and, more important, the general apathy and unwillingness of the soldiers to fight the 26th of July Movement rebels.

Meanwhile, the traditional Liberal and Conservative parties lost much of their power and influence and were relegated to a less important role as new parties came into existence, which also failed to create a strong and stable role for themselves and collapsed as they were unable to face the new realities created by the Batista military dictatorship. In contrast, in Venezuela, the social-democratic Acción Demócratica (AD) and the Social-Christian Party (COPEI) managed to survive the dictatorship of Marcos Pérez Jimenez and emerged as strong and stable parties of the social and economic status quo after the Venezuelan dictatorship was overthrown in January 1958.

In 1944, Batista’s candidate lost the elections to the first of two liberaldemocratic, but very corrupt, governments. These governments preserved, on the whole, the democratic features of the progressive 1940 Constitution, and introduced institutional changes such as the creation of a national bank to regulate the monetary and financial systems in the island. Nevertheless, they were unable to change the fundamental features of the social-political structure of the post-1933 Cuba. These were the features that remained unchanged all the way up to the eve of the revolution of 1959.

A large but weak working class

One of the main features of the large working class in Cuba on the eve of the revolution was that a substantial part of it was rural and centered on the seasonal sugar industry. The great majority of these sugar workers were wage-earning agricultural workers cutting, collecting, and transporting the cane, with a minority of industrial workers working on the processing of sugar and the maintenance, repair, and upkeep of the sugar mills. As we shall see later in greater detail, this made Cuba different from other lessdeveloped countries where peasants dominated the rural landscape engaged in self-subsistence agriculture. It is true that in the 1950s new sectors of the working class had emerged as a result of a degree of diversification of the economy away from the sugar industry despite the constraints imposed by economic treaties with the United States. These included, besides the extraction of nickel and cobalt in eastern Cuba and oil refineries, the production of pharmaceutical products, tires, flour, fertilizers, textiles such as rayon, detergents, toiletries, glass, and cement.10 Nevertheless, sugar continued at the heart of the Cuban economy with the most important sector of the agricultural proletariat associated with it.

A study published in 1956 by the US Department of Commerce based on the 1953 Cuban census, cites farm laborers, including unpaid family workers, as constituting 28.8 percent of the labor force in the island, which could be considered as a rough approximation of the size of the rural working class in the 1950s. The same study also cites a group classified as farmers and ranchers as constituting an additional 11.3 percent of the total labor force. It is likely that the figures of both groups fluctuated through time as a result of movement between those two groups of poor farmers and ranchers seeking to seasonally supplement their income by selling their labor in the sugar industry, and also as a result of substantial migration from rural to urban areas. Even so, those figures indicate a much higher proportion—more than double—of salaried rural workers compared to peasants in the countryside.

It is thus ironic that the peasants that Fidel Castro came into contact with in the Sierra Maestra were not representative of the Cuban rural labor force. (Sugar is typically planted in flat rather than mountainous lands.) The structure of Cuba’s rural labor force in the 1950s also helps to explain why once Fidel Castro and his close associates adopted the Soviet system, they had a much easier time collectivizing agriculture into state farms than was the case in other Communist countries with large peasantries.

Besides the agricultural proletariat, Cuba also had a larger and more important urban working class. The same 1956 study classified 22.7 percent of the Cuban labor force under the category of craftsmen, foremen, operatives, and kindred workers, 7.2 percent as clerical and kindred workers, and 6.2 percent as sales workers. Service workers, except private households, constituted 4.2 percent of the urban working class, and private household workers 4.0 percent. These categories could be considered a rough approximation of the urban working class, for a total of 44.3 percent of the total labor force in the island.11

Over fifty percent of this two million rural and urban labor force was unionized, mostly under the control of the very corrupt Mujalista union bureaucracy, whose leader Eusebio Mujal had supported Batista since his second military coup in 1952, promising to keep labor peace in exchange for being ratified as the principal union leader. For its part, Batista’s government refrained from an immediate attack on labor’s gains, although it did not take long for it to gradually, but substantially, erode labor’s wages and working conditions. Mujal became even more bound to Batista after the dictator outlawed the Popular Socialist Party (PSP), the name adopted by the Communists at the time of the Soviet alliance with the United States during the Second World War, a move that increased Mujal’s control and that further eroded the already limited influence of that party on the organized working class in the island. According to an internal survey conducted in 1956 by the PSP, only 15 percent of the country’s two thousand local unions were led by Communists or by union leaders who supported collaboration with the PSP.12

The Communist Party’s influence on the Cuban working class had its militant heyday in the late twenties and early thirties, at the time of its “third period” ultra-left and sectarian politics. Its growth displaced the hold that the anarchists had on the working class from the late nineteenth century until the mid 1920s, both in Cuba and in the predominantly Cuban tobacco enclaves in Key West and Tampa in Florida to which Cuban tobacco workers would migrate—before there were immigration controls—because of strikes or poor economic conditions in the island. That growth allowed the CP to play a leading role in the 1933 revolution against the Machado dictatorship, a revolution in which the working class played a significant part. However, the CP “third period” policy against supporting the new nationalist revolutionary government that the Roosevelt administration refused to recognize significantly contributed to the failure of that revolution. Moreover, under the popular front policy adopted by the CP later on, and as a result of the nationalists refusing to work with the CP because of its conduct in the 1933 revolution, the Cuban Communists made a deal with Batista in 1938 providing him with political and electoral support in exchange for the CP being handed the official control of the Cuban labor movement. The defeat of the candidate supported by Batista and the Communists in the 1944 elections and the Cold War that began a few years later, dealt a severe blow to Communist political influence in general and their trade union influence in particular.

It was then that the labor representatives of the Auténtico Party—the former revolutionary nationalists of the 1930s—with Eusebio Mujal among them, who, along with other independent labor leaders who could be loosely identified as nationalist, took over the unions, sometimes based on the use of force and other assorted gangster methods. Soon after, Mujal emerged as the top leader of the only trade-union confederation, a role that he continued to play under Batista.

Opposition to the dictatorship grew among the large majority of Cubans. The working class found itself under the yoke of the double dictatorship of Mujal in the unions and of Batista in the country as a whole. Remarkably, as some authors have shown, there were many labor struggles that took place in that period, some with an open anti-Batista agenda.13 The Mujalista bureaucracy did not have total control of working-class unrest and there were some militant unions—like that of the bank workers—that managed to escape Mujal’s vise. However, these struggles did not translate into a strong and visible independent working-class organization opposed to the government. This was due to the fragmentary character of these struggles that lacked the continuity and cumulative impact that would have made a strong and independent working-class organization possible.

This was the context in which Fidel’s 26th of July Movement called for a general strike in April of 1958. The strike was a total defeat: the majority of the workers, union and nonunion, did not respond, and the minority who did was violently repressed by Batista’s police. This had very serious consequences for the revolutionary movement, as well as for the role that the working class would play in the revolution. On May 3, 1958, less than a month after the defeat of the April strike, the leadership of the movement met with Fidel Castro at Altos de Mompié in the Sierra Maestra to discuss the strike failure and how to proceed with the struggle.14 One result of this meeting was that Castro solidified his control of the movement by being named general secretary and commander- in-chief of the rebel army. The other was that the movement adopted guerrilla warfare as its central strategy and assigned the general strike to a secondary role only as the popular culmination of the military campaign. After Batista and his immediate entourage fled the country on New Year’s Day in 1959, Fidel Castro and the 26th of July Movement called for a general strike to paralyze the country to prevent a military coup. As the possibility of a coup greatly receded less than twenty-four hours after Batista’s departure, the planned general strike rapidly turned into a huge, multiclass national festival to celebrate the victory of the rebels and to greet Fidel Castro and his rebel army in its long east-to-west triumphant procession towards Havana where they arrived on January 8. This is how the active, organized fragments of the Cuban working class, and even more so the far larger number of workers who sympathized as individuals with the revolution, ended up as supporting actors instead of being the central protagonists in the successful struggle to overthrow the Batista dictatorship. The FONU (Frente Obrero Nacional Unido)—a broad workers’ front formed and led by the 26th of July Movement in 1958, which included every anti-Batista political formation, and especially the Communists—was no political or organizational match for Fidel Castro and the broader 26th of July Movement, and only played a secondary role in the overall anti-Batista struggle. Neither the urban nor the rural working class played a central role in that struggle.

How Fidel Castro emerged:

The interface of social structure and political leadership

When the Batista coup took place on March 10, 1952, Fidel Castro had graduated two years earlier from the law school at the University of Havana. He was one of the many children of Ángel Castro, a turn-of-the-century Galician immigrant who became a wealthy sugar landlord in eastern Cuba. Although he never showed any political inclination while studying at the elite Jesuit Colegio Belén high school, after he entered the University of Havana in 1945 he became involved with one of the several political gangster groups at the university, for the most part formed by demoralized veterans of the 1933 Revolution battling each other for the no-show jobs and other kinds of sinecures used by the Auténtico governments then in power to coopt and neutralize the former revolutionaries.15 Then, while still in law school, he participated in two important events that came to have a deep influence on him: one was the 1947 Cayo Confites expedition that intended to sail to the Dominican Republic from a key off the Cuban coast to provoke a revolution against the Trujillo dictatorship. The expedition never got off the key due to Washington’s pressure on the Cuban army to squash it. The other event was the so-called “Bogotazo,” the massive rioting that took place in Bogotá, Colombia, after the assassination of Liberal Party leader Eliecer Gaitán in 1948. For Fidel Castro, the Cayo Confites expedition of some 1,200 men was an example of what he regarded as bad organizing and sloppy, hasty recruitment methods that led to the incorporation of “delinquents, some lumpen elements and all kinds of others.”16 Concerning the “Bogotazo,” although Castro had been impressed by the eruption of an oppressed people and by their courage and heroism, he remarked that

there was no organization, no political education to accompany that heroism. There was political awareness and a rebellious spirit, but no political education and no leadership. The [Bogotazo] uprising influenced me greatly in my later revolutionary life . . . I wanted to avoid the revolution sinking into anarchy, looting, disorder, and people taking the law into their own hands. . . . The [Colombian] oligarchs—who supported the status quo and wanted to portray the people as an anarchic, disorderly mob—took advantage of that situation.17

It was the disorganized and chaotic nature of these failed enterprises that shaped much of Fidel Castro’s particular emphasis on political discipline and suppression of dissident views and factions within a revolutionary movement. As Fidel Castro wrote to his then close friend Luis Conte Agüero in 1954,

Conditions that are indispensable for the integration of a truly civic movement: ideology, discipline and chieftainship. The three are essential, but chieftainship is basic. I don’t know whether it was Napoleon who said that a bad general in battle is worth more than twenty good generals. A movement cannot be organized where everyone believes he has the right to issue public statements without consulting anyone else; nor can one expect anything of a movement that will be integrated by anarchic men who at the first disagreement take the path they consider most convenient, tearing apart and destroying the vehicle. The apparatus of propaganda and organization must be such and so powerful that it will implacably destroy him who will create tendencies, cliques, or schisms or will rise against the movement.18

While still at the university, Castro later joined the recently formed Ortodoxo Party. It is clear that he was already involved in leftist politics and was interested in not only national but also international issues, such as the Puerto Rican independence movement and opposition to Franco’s Spain. The Ortodoxo Party was a broad political formation that had been created as a split off the increasingly corrupt Auténtico Party that held national elective office from 1944 until Batista’s coup in 1952. It was a progressive reform party that focused on the fight against official corruption and, among its various political positions, opposed Communism on democratic political grounds while also defending the democratic rights of the Cuban Communists against the local version of McCarthyism. Most important, it attracted a large number of idealistic middle- and working-class youth that later became the most important source of recruitment for Fidel Castro’s 26th of July Movement.

Castro became a secondary leader in that party and eventually ran as a candidate for the Cuban House of Representatives in the 1952 elections that never took place because of Batista’s coup. It was in response to that coup that Fidel Castro began to advocate and organize the armed struggle against Batista within the Ortodoxo Party itself. However, the party soon split into various factions, some of them abstentionist and some others favoring unprincipled coalitions with traditional, discredited parties opposed to Batista. None of them were able to prosper under the unfavorable conditions of a military dictatorship that differed dramatically from the functioning of an electoral party in a constitutional, even if corrupt, political democracy. The other anti-Batista parties were, for a variety of reasons, no better than the Ortodoxos. That is why Fidel Castro and his close associates started to act on their own and secretly began to recruit sections of the Ortodoxo Party and unaffiliated youth for the attack on the Moncada barracks scheduled for July 26, 1953. The political vacuum in the opposition to Batista considerably helped his recruitment efforts, since from the very beginning his consistent and coherent line of armed struggle against the dictatorship attracted the young people who had become thoroughly disillusioned with the irrelevance of the regular opposition parties.

Along with his emphasis on armed struggle as the strategy to fight against Batista, Fidel’s attack on the Moncada barracks was premised on a social program that included agrarian reform—a widespread popular aspiration—with compensation for the expropriated landlords, and a substantial profit-sharing plan for workers in industrial and commercial enterprises. These measures were not socialist or, aside from the nationalization of public utilities, collectivist, but were radical for the Cuba of the 1950s. Castro explicitly outlined this radical program in the speech that he gave at his and his fellow fighters’ trial after the Batista forces defeated the attack, which was later published under the title History Will Absolve Me, the final sentence of that speech.

It did not take long before Castro concluded that the combination of armed struggle with a radical social program was an obstacle to widening support for his 26th of July Movement—which he had founded after he and his Moncada companions were amnestied by Batista in 1955—and increasing his group’s influence within the anti-Batista movement, which on the whole was liberal-populist and progressive but not radical. That is why, although he continued to insist in the armed struggle to overthrow Batista (a position he never abandoned), by 1956 he had significantly modulated his social radicalism. This became clearly articulated in the politically militant but socially moderate Manifesto that he co-authored with Felipe Pazos and Raúl Chibás, two very prestigious figures of Cuba’s progressive circles, in the Sierra Maestra on July 12, 1957.19

The Manifesto, which rapidly became far better known than Castros’ History Will Absolve Me, conferred an enormous degree of legitimacy among the progressive anti-Batista public to Castro’s 26th of July Movement at a time when it had not yet fully consolidated itself in the Sierra Maestra. It turned out to be, in conjunction with a number of small but significant military victories against Batista’s troops, a major step in Fidel Castro’s journey towards becoming the hegemonic figure of the opposition camp. Moreover, the publication of the Manifesto in Bohemia, the Cuban weekly with the largest circulation in the island, during a period when Batista’s censorship had been suspended, deeply affected thousands of people, further propelling the 26th of July Movement towards their unrivaled hegemony over the other groups engaged in armed rebellion who had failed in their own confrontations with Batista’s armed forces. The Manifesto fell on fertile ground in a political culture where the notion of revolution, in the sense of a forceful overthrow of an illegitimate government, had wide acceptance, especially when the potentially divisive issue of a revolutionary, as distinct from a progressive reformist, social program, was set aside.

It is also worth underlining that Fidel Castro, like other left-inclined Cuban oppositionists (except for the Communists), kept his anti-imperialist politics to himself throughout the struggle against Batista, both in his more socially radical and moderate periods. Although he revealed his anti-imperialist sentiments in private to close associates such as Celia Sánchez,20 in public he limited himself to the democratic critique of US foreign policy for its support of Batista and other Latin American dictators. And when his younger brother Raúl Castro, as head of the Frank País Second Front elsewhere in Oriente province, ordered the kidnapping of American military personnel from the Guantánamo Naval Base to stop the United States from assisting the Batista dictatorship in its bombing of the rebel areas in June 1958, Fidel immediately ordered their release.

For a variety of reasons, anti-imperialism had become dormant in the Cuban political scene since the 1930s. Only the Communists and their close periphery used the term to describe and analyze US policies towards Cuba and Latin America.21 Yet, the Communists contributed to the fading of the anti-imperialist sentiment with the Soviet alliance with the United States in World War II, and their support for the Roosevelt administration, a popular policy in the island in the Communist and non-Communist left alike.

It was Fidel’s tactical ability to retreat from potentially divisive programmatic social issues that revealed him as the thoroughly political animal and master political operator and tactician he was, endowed with an acute sense of Cuban political culture and an uncanny ability to understand and to take advantage of specific political conjunctures to broaden his political base and support.

Part of what gave him room to tactically maneuver substantive political issues was that the inner core of the people he relied on was an heterogeneous group of militant “classless” individuals, in the sense of their not having a connection to any of the then existing organizations of any class. They were therefore not committed to, or bound by, any particular social program. And those who did, such as Raúl Castro and Ernesto “Che” Guevara, knew Fidel well enough to trust him to move the political dynamic of the movement in a generally left direction.

Confirming the class heterogeneity of the group of people closest to Fidel, historian Hugh Thomas notes that the people who joined Fidel in the attack on the Moncada barracks on July 26, 1953, came from a wide variety of social backgrounds, including accountants, agricultural workers, bus workers, businessmen, shop assistants, plumbers, and students. Thomas further notes that the group of eighty-one persons that accompanied Fidel in the Granma expedition to Cuba in late 1956—nineteen of whom had participated in the Moncada attack—might have had an overall higher education than the Moncada group, but that it was socially heterogeneous, too. According to Thomas, both of these groups comprised Castro’s inner group of loyal followers.22 This inner group was later enlarged by people selected from the new urban volunteers and from a few thousand peasants in the Sierra Maestra and elsewhere in eastern Cuba. It should be noted that, with a small number of important exceptions, the peasant recruits had little or no history of organized peasant struggles and that in contrast with the rebel army recruits from towns and cities in Cuba’s eastern Oriente Province, the peasant recruits did not generally play any major leadership roles after the revolutionary victory.23

In addition to his political talent, Fidel Castro ascendance in the antiBatista movement benefited from the occurrence of events beyond his control that cannot be explained either in terms of the characteristics of Cuba’s social structure or his own extraordinary political skills. To begin with, he physically survived the armed struggle against Batista without any significant injury, something that cannot be taken for granted when considering that out of the eighty-one people who accompanied him to Cuba in the boat Granma, no more than twenty survived the invasion and its immediate aftermath. Even more important was the failure of the other revolutionary groups to overthrow Batista by force, and the death of other revolutionary leaders who could have potentially challenged his leadership. One of them, José Antonio Echeverría, was a popular student leader who founded the Directorio Revolucionario, another political group engaged in the armed struggle against Batista. He was killed in a confrontation with Batista’s police on March 13, 1957 after attempting to simultaneously capture a radio station (where he managed to broadcast a brief speech shortly before being shot after he left the station) and carry out an assault on the Presidential Palace. The other potential rival was Frank País, the national coordinator of the 26th of July Movement, killed by Batista’s police in the streets of Santiago de Cuba on July 30, 1957. País was an independent-minded revolutionary who emphasized the importance of a clear political program and a well-structured 26th of July Movement, in contrast with the unclear, weakly structured organization more easily subject to the control of the top leader model that Fidel favored.24

But Fidel Castro’s emergence and ascendance to the top of the anti-Batista movement, his victory over Batista on January 1, 1959, and the great deal of political power he acquired after victory cannot be accounted for based only on his undisputable political talents and his good fortune. It was the interface between those two factors with Cuba’s social structure of that time—devoid of an oligarchical ruling class with firm organic ties to an ideologically committed army hierarchy, which could have effectively repressed attempts against its power, and of stable political organizations and parties that could have channeled the popular discontent—that made his trajectory possible.

Fidel Castro in power

Fidel Castro’s victory surpassed anybody’s expectations—his forces managed to eliminate the army from the Cuban political scene on January 1, 1959—and led him to power with an immense and virtually unchallengeable popularity. All other political groups and personalities had either been discredited or lagged far behind Fidel in popular support and legitimacy.

Once in power, Fidel behaved in a remarkably similar manner as when he was in the Sierra: as the unquestionable leader of a disciplined guerrilla army controlled from above that strictly follows the military orders of their superiors. To this he added, once in power, his extremely intelligent use of television and the public plaza to appeal to the widespread radicalization and growing anti-imperialist sentiment of the people at large.

Although he undoubtedly consulted with and listened to those in his inner circle, he acted on his own, even disregarding previous agreements while often refusing to accept criticism. He treated his close comrades as consultants and not as full peers embarked in a joint project.25 His key consideration was to be the one decision maker and remain in control of the political situation.

That is why, after victory, Fidel Castro prevented any attempt to transform the 26th of July Movement from the amorphous, unstructured group it had been during the struggle against Batista into a democratically organized, disciplined party. Doing so would have limited the room for his political maneuvering, particularly early in the revolution when his movement was still politically heterogeneous. At that time, such a party would have inevitably included the political tendencies that he abhorred. It was only in 1965—long after all the major social-structural changes had already been implemented and the liberals, social democrats, and independent anti-imperialist revolutionaries of the 26th of July Movement (see below) had either left the country or had been marginalized—that a so-called “democratic centralist” Communist Party uniting the 26th of July Movement with the Communists (and with the much smaller Directorio Revolucionario) was finally established in Cuba. However, for reasons discussed later, this party did not significantly impinge on Fidel’s ultimate control of what happened in Cuba.

Fidel’s turn to communism

Even today, most American liberals and many radicals contend that it was the United States’ imperialist policies that “forced” Fidel Castro into the hands of the Soviet Union and Communism. To be sure, the United States responded to the victorious Cuban Revolution in a predictably imperialist fashion similar to the way it had responded, earlier in that decade, to the democratically elected reform government of Jacobo Árbenz in Guatemala in 1954 and the Iranian nationalist regime of Mohammad Mosaddegh in Iran in 1953. However, the view that Fidel Castro was “forced” or “compelled” to adopt Communism is misleading because it deprives him and his close associates of any political agency and implicitly conceives them as politically blank slates open to any political path had US policy towards Cuba been different.

In fact, Fidel and the other revolutionary leaders did have political ideas. This became clear soon after the victory of the Cuban Revolution with the creation, in the revolutionary camp overwhelmingly composed by members of the 26th of July Movement, of a powerful pro-Soviet tendency oriented to an alliance with the PSP (Popular Socialist Party), the old pro-Moscow Cuban Communists. This tendency was led by Raúl Castro, a former member of the Juventud Socialista (the youth wing of the PSP), and by Che Guevara, who had never joined a Communist Party but was then pro-Soviet and an admirer of Stalin, notwithstanding the fact that more than two years had elapsed since Khruschev’s revelations of Stalin’s crimes in 1956. The new revolutionary government also had in its ranks an important non-Communist, anti-imperialist left (e.g., Carlos Franqui, David Salvador, Faustino Pérez), plus liberal (Roberto Agramonte, Rufo López Fresquet) and social democratic (Manuel Ray, Manuel Fernández) tendencies.

Fidel Castro did not immediately commit (at least in public) to any of those tendencies. Although he had been a leftist for many years and intended to make a radical revolution, he left it to the existing relation of forces inside Cuba and abroad, and to the tactical possibilities available to him given the existing relation of forces, to determine the path to follow while maneuvering to ensure that he remained in control. Had he gone in a different direction, Che Guevara would have immediately left the island and Raúl Castro would have gone into the opposition. Information found in the Soviet archives show that Raúl Castro briefly considered breaking with his older brother Fidel during the first half of 1959 when Fidel’s commitment to working with the Communists was in doubt.27

By the fall of 1959, less than a year after victory, it became clear that Fidel Castro was moving in the direction of an alliance with the USSR and, months later, towards the transformation of the Cuban society and economy into the Soviet mold. While he later claimed that he had been a “Marxist Leninist” all along, this was more likely a retrospective justification of the political course he took later, rather than an accurate account of his early political ideas. His decision was probably influenced by the fact that the victory of the Cuban Revolution coincided with the widespread perception in the late 1950s and early 1960s that the balance of world power had shifted in favor of the USSR. The Soviet’s test of its first intercontinental ballistic missile and the launch of Sputnik in 1957 had generated serious concerns in the US regarding Soviet supremacy in those key areas. And while the US economy was growing at a rate of 2 to 3 percent per year, various US government agencies had estimated that the Soviet economy was growing approximately three times as fast.28 Also, quite a few things were happening in the Third World that favored Soviet foreign policy, such as the Communist electoral victory in Kerala, India in 1957,29 and a left-wing coup that overthrew the Iraqi monarchy in 195830 (countered by a US invasion of Lebanon that followed shortly thereafter). Successes in Laos31 and a domestic turn to the left by Nasser in Egypt and by Sukarno in Indonesia (both allies of the USSR) further bolstered Soviet power and international prestige.32 This constellation of events may have persuaded Fidel that were he to follow the Communist road, he could count on the rising power of the USSR to confront the growing US aggression against Cuba, support a total break with Washington, and implement a Soviet- type of system for which he had an affinity given the great social and political control that it would confer on him.

As an early step in his path towards Soviet-type Communism, in November 1959 Fidel Castro personally intervened in the Tenth Congress of the Confederation of Cuban Workers (CTC—Confederación de Trabajadores de Cuba), the union central established in 1938, to rescue the Communists and their allies within the 26th of July Movement from a serious defeat in the election of the Confederation’s top leaders. Consistent with the findings of their 1956 survey, the PSP had obtained only 10 percent of the votes in the union elections that had taken place earlier that year as well as in the delegate elections to the Congress itself. Fidel Castro’s intervention allowed the 26th of July unionists friendly to the Communists to take control of the Confederation in what proved to be the short term. That was followed, in the subsequent months, by the purge of at least half of the union officials elected in 1959—some were also imprisoned—who were hostile to the PSP and their allies within the 26th of July Movement, thus consolidating the control of the latter two groups over the union movement. Shortly afterwards, in August 1961, new laws were enacted bringing the functioning of the Cuban unions into alignment with those of the Soviet bloc by subordinating them to the state and treating them primarily as a means to increase production and as conveyor belts of the state’s orders. In November 1961, at the eleventh congress of the CTC, the hard polemics and controversies that had gone on in the Tenth Congress were replaced with the principle of unanimity.

Then, topping it all, Lázaro Peña, the old Stalinist labor leader who, with Batista’s consent, had controlled the trade-union movement in the early forties (during Batista’s first period in power) was elected to the top post of secretary general of the CTC. With this move, Fidel Castro dealt the last blow to the last vestiges of autonomy of the organized working class and subjected it to his total control. It should be noted that notwithstanding the loss of some of their pre-revolutionary labor conquests, most Cuban workers were pleased with the gains they obtained under the young revolutionary regime, and therefore they did not protest the state takeover of their unions.

The sovietization of the island proceeded to encompass other areas of Cuban society, all under Fidel’s direction. In May 1960, the government seized the opposition press and replaced it with government-controlled monolithic media. This was clearly a strategic, long-term institutional move since the country was not facing any kind of crisis at that particular time. Other pro-revolutionary but independent newspapers, such as La Calle, were shut down some time later, as was Lunes de Revolución, the independent cultural weekly of Revolución, the 26th of July Movement newspaper. The abolition of additional independent autonomous organizations continued with the institution, by Fidel, of the Cuban Federation of Women (Federación de Mujeres Cubanas—FMC) in August 1960, which led to the disbanding of more than 920 preexisting women’s organizations, and their incorporation and assimilation into the FMC which became, by government fiat, the sole and official women’s organization.

Earlier, toward the end of 1959, Fidel’s government started to limit the autonomy of the “sociedades de color,” the mutual-aid societies that for many years constituted the organizational spine of Black life in Cuba. Few “sociedades” remained after that, but they totally disappeared by the midsixties, after Fidel’s government proclaimed that, given the gains that Black Cubans had made under the revolution on the basis of class-based reforms and the abolition of racial segregation, the problems of racial discrimination and racism had been resolved. For the next thirty years, total silence prevailed on racial questions, notwithstanding the evident institutional racism in a society that was being ruled by whites, and that lacked any significant affirmative action programs to address the situation.33 That silence basically continued the prerevolutionary taboo avoiding any open discussion of race that harked back to the so-called race war of 1912, which in fact never was a real war, but a massacre of Black Cubans.34

On April 16, 1961, shortly before the US Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba, Fidel Castro proclaimed the “socialist” character of the revolution. By that time, all of the above-mentioned changes, along with the nationalization of most of the Cuban economy—a process that ended in 1968, with the nationalization of even the tiniest businesses in the island probably making Cuba the most nationalized economy in the world—had set the foundations of a Caribbean replica of the Soviet system.35 The finishing touch was the formation of a single ruling party, a process that was finalized, after two previous provisional organizations, with the official foundation of the Cuban Communist Party in October 1965. Structured in the Soviet mold, this party allowed no internal dissent or opposition, and in effect ruled over the economy, under the leadership and control of Fidel Castro, through: (1) its “mass organizations,” such as the FMC (the women’s federation) and the CTC (the union central), that served as conveyor belts for its decisions and orders; and (2) its control of the mass media—all the newspapers, magazines, radio, and television stations in the island—based on the “orientations” that came from the Ideological Department of the Central Committee of the Cuban Communist Party.

Although the Cuban Communist Party followed the fundamental outlines of the Soviet-style parties in the USSR and Eastern Europe, it also had characteristics of its own. One was the great emphasis it placed on popular mobilization—a device introduced by Fidel Castro—devoid, however, of any real mechanisms of popular democratic discussion and control (a feature that it did share with its sister parties in the Communist bloc). Another feature present in many of those mobilizations was pseudo-plebiscitarian politics, also introduced by Fidel, of having the participants “vote” right then and there, raising their hands to show popular approval for the leadership’s initiatives.36

Part 2 of this article will appear in ISR 113.

- I use the term Communist for the sake of clarity, but I do not link present-day Communism with the communism of Marx, Engels, and many other revolutionaries who predate the rise of Stalinism. I also use communism in a generic sense to describe a class and socioeconomic system even though each communist country had its own peculiarities. Marxists use the term capitalism similarly, even though capitalist states, like the United States, South Korea, and Norway, are not identical.

- Pedro C. M. Teichert, “Analysis of Real Growth and Wealth in the Latin American Republics,” Journal of Inter-American Studies I, April 1959, 184–185.

- Ibid.

- Marifeli Pérez-Stable, The Cuban Revolution: Origins, Course and Legacy, 2nd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 29.

- Jorge Ibarra, Prologue to Revolution: Cuba, 1898–1958, trans. Marjorie Moore (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 1998), 162.

- Yeidy M. Rivero, Broadcasting Modernity: Cuban Commercial Television 1950–1960 (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2015).

- See Samuel Farber, Revolution and Reaction in Cuba, 1933–1960: A Political Sociology from Machado to Castro (Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 1976).

- John Paul Rathbone, The Sugar King of Havana: The Rise and Fall of Julio Lobo, Cuba’s Last Tycoon (New York, Penguin, 2011), 210–211. Rathbone claims that Lobo gave $25,000 to the 26th of July Movement because the Movement threatened to burn his cane fields. However, shortly after the revolutionary victory the Cuban press, freed from any government censorship, reported that Lobo financially supported the revolution out of his own free will.

- One of Batista’s first decrees after his successful military coup on March 10, 1952, was to order a substantial increase in the salaries of soldiers and policemen.

- Jorge Ibarra, Prologue to Revolution, 18–19.

- US Department of Commerce, Bureau of Foreign Commerce, Investment in Cuba: Basic Information for United States Businessmen, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1956, 183.

- Jorge Ibarra, Prologue to Revolution: Cuba, 1898–1958,170.

- Steve Cushion, A Hidden History of the Cuban Revolution: How the Working Class Shaped the Guerrilla’s Victory (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2016).

- Julia Sweig, Inside the Cuban Revolution: Fidel Castro and the Urban Underground (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002), 150.

- See the more detailed discussion of political gangsterism in Cuba in Samuel Farber, Revolution and Reaction in Cuba, 1933–1960, 117–122.

- Fidel Castro, My Early Years, ed. Deborah Shnookal and Pedro Alvarez Tabío, (Melbourne, Australia: Ocean Press, 1998), 98. For more details about the Cayo Confites expedition and the politics behind it see Charles D. Ameringer, The Caribbean Legion. Patriots, Politicians, Soldiers of Fortune, 1946–1950 (University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1996).

- Ibid, 126–127.

- Luis Conte Aguero, 26 Cartas del Presidio (Havana: Editorial Cuba, 1960), 73. These letters were published before Conte Aguero’s break with Fidel Castro. Castro’s emphasis.

- For the text of the Sierra Maestra Manifesto see Rolando E. Bonachea and Nelson P. Valdés, eds., Revolutionary Struggle 1947–1958, vol. 1 of The Selected Works of Fidel Castro (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1972), 343–48.

- In June 1958, Fidel Castro privately wrote to Celia Sánchez that when the war against Batista finished, a bigger and much longer war would begin against the United States. Carlos Franqui, Diario de la Revolución Cubana, 473.

- Thus, for example, an official pamphlet of the 26th of July Movement published in 1957 danced around the term imperialism “as already inappropriate to the American continent” although there were still forms of economic penetration and political influence similar to it. The pamphlet proposed a new treatment of “constructive friendship” so Cuba could be a “loyal ally of the great country of the North and at the same time safely preserve the capacity to orient its own destiny.” Movimiento Revolucionario 26 de Julio, Nuestra Razón: Manifiesto-Programa del Movimiento 26 de Julio, in Enrique González Pedrero, La Revolución Cubana, (Ciudad de México: Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Políticas y Sociales, 1959), 124.

- Hugh Thomas, “Middle Class Politics and the Cuban Revolution,” in The Politics of Conformity in Latin America, ed. Claudio Véliz (London: Oxford University Press, 1967), 261.

- See the detailed biographies of many revolutionary generals in Luis Báez, Secretos de Generales, Havana: Editorial Si–Mar, 1996.

- Unlike most other top leaders of the 26th of July Movement, Frank País had strong roots in the life of Cuban civil society. He and his family were very active in the Baptist Church, and his parents were among the tiny minority of Spanish Protestant immigrants to Cuba.

- Carlos Franqui, Diario de la Revolución Cubana, (Paris: Ruedo Ibérico, 1976), 611.

- For a detailed analysis of Che Guevara’s politics see Samuel Farber, The Politics of Che Guevara: Theory and Practice (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2016).

- Aleksandr Fursenko and Timothy Naftali, “One Hell of a Gamble,” Khrushchev, Castro, and Kennedy 1958–1964 (New York: W.W. Norton and Co., 1997), 18.

- Ibid., 77.

- Jerry F. Hough, The Struggle for the Third World: Soviet Debates and American Options (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 1986), 120.

- William Taubman, Khrushchev: The Man and His Era (New York: Norton, 2003), 402.

- Herbert Dinerstein, The Making of a Missile Crisis: October 1962 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976), 113.

- Jerry F. Hough, The Struggle for the Third World, 120; and Jean Lacouture, Nasser: A Biography (New York: Knopf, 1973), 230–35, 244.

- For a recent brief but thorough examination of “structural racism” in Cuba see Sandra Abd’Allah-Alvarez Ramírez, ¿Racismo “estructural” en Cuba? Notas para el debate” Cuba Posible, September 6, 2017. https://cubaposible.com/racismo-estructu....

- Silvio Castro Fernández, La Masacre de los independientes de color en 1912, 2nd edition (La Habana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, 2008).

- For details of the “revolutionary offensive” that nationalized all urban businesses see my article “Cuba in 1968,” Jacobin, April 30, 1968, https://jacobinmag.com/2018/04/cuba-1968....

- An authentic plebiscite, such as the “Brexit” elections in Great Britain, assumes extensive public discussion previous to the elections, ending with a “Yes” or “No” secret vote at the ballot box.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Google+

Google+ Tumblr

Tumblr Digg

Digg Reddit

Reddit StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon