1968: Year of revolutionary hope

This article is based on a speech JOEL GEIER, associate editor of the ISR, gave at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign on March 26, 2008.

1968 WAS a year of revolutionary hope. Most of the time people have little hope. They accept or adapt to existing conditions around them, even miserable ones. They feel powerless; they don’t think they can change things. Most of the time revolutionaries are a small, marginalized minority, considered unrealistic and utopian. Revolution is seen as being impossible; people, we are told, are too apathetic or ignorant—they’ll never fight back. The working class has been bought off, it’s fat and contented; so forget it, relax, enjoy your own life, that’s the best you can hope for. And then suddenly, unexpectedly, out of nowhere there are huge explosions from below, in which millions of people heroically engage in radical struggles that totally transform the world, politics, and themselves. They reach for revolutionary solutions to the oppressive conditions they live under, and large numbers of them come to revolutionary consciousness.

In this country, for example, tens of thousands of people thought of themselves as revolutionaries in the late 1960s. By 1970, 3 million Americans, according to public opinion polls, believed that a revolution was necessary in the United States. A majority of young Blacks identified with the Black Panther Party.

We’re told those things can’t happen in the United States—that millions of people could never consider themselves to be revolutionaries—but they did. Large numbers of people wanted not just any change; they wanted a sweeping radical, revolutionary socialist change. They didn’t just want to elect somebody different; they wanted to do away with rulers and ruled. They wanted to do away with rich and poor, with bankers and bosses. They wanted to run their own lives, in what was called participatory democracy. Participatory democracy was the idea that we should have the right to make the most important decisions that affect our lives, and that we should determine the conditions under which we live. And the key word of 1968 was liberation—national liberation, Black liberation, and women’s liberation.

As the French put it, “with the eating comes the appetite.” As people began to see that there could be change, new movements that had not previously existed, like the women’s and gay movement arose. People began to speak of new needs, new demands, that “all of us want to change. We want an end to our oppression. We want an end to our exploitation. We want to run things. We want power to the people. We want popular power. We want workers’ control.” Those ideas of the revolutionary socialist movement, which had been marginalized for a generation and have been marginalized for a generation again, became popular ideas for millions of people in 1968, and they spread everywhere.

I remember one of the slogans we used to chant on demonstrations. “London, Paris, Rome, Berlin, we will fight, we will win.” Every place in Europe exploded, both sides of the Iron Curtain, in Poland and in Czechoslovakia; in Western Europe, in Italy and Spain; in Asia, in India and Pakistan; and in Latin America, in Mexico, Argentina, and elsewhere. Millions of people throughout the world burst into struggle. The global nature of the uprising raised the horizons of movement activists, turned us into internationalists, and made us aware that we were allied to, and part of, the struggle for liberation everywhere, that we were the American arm of an international revolutionary socialist movement. Because of time limitations I have to limit my remarks to two key places—the United States and France, and what occurred that led to the enormous radicalization in those countries.

In the 1960s the radicalization started inside the United States. It began with the sit-ins of the civil rights movement in the South in February of 1960. And by 1968 the radical movement in the United States was probably larger, and more active, than in practically any other country in the world. It wasn’t going to remain so; after 1968 huge revolutionary movements were going to appear everywhere, but going into 1968 it was the United States that was a center of world radicalism. It’s hard to believe that today given how conservative American conditions are now, but that radicalization was essentially based upon two things—the Vietnam War and the resistance to it, and the Black liberation movement. Let’s just start with the Tet Offensive, which is what opened up the huge international radicalization.

During the Tet Offensive, which began on January 31, 1968, 100,000 National Liberation Front (NLF) troops entered Saigon and all the provincial capitals in a battle for the cities of Vietnam. Huge numbers of Vietnamese people were aware of this; they had to provide support for the entry of 100,000 troops into the cities. Yet not one person told the Americans, who were totally unaware of the immanent attack. It was an enormous shock. It was very clear that the NLF had the overwhelming support of the Vietnamese people against an American invasion. The U.S. had been at war for three years, and there had been the usual promises of “successful surges” where the politicians and the media said there’s a light at the end of the tunnel, the corner has been turned, that the United States is winning the war. After Tet, it became clear to the American population that the United States could not possibly win this war. The war, however, went on for another seven years.

The Tet Offensive led to the massive shift in public opinion against the war, and out of that, the growth of the U.S. antiwar movement that already existed as a network of groups active on an almost daily basis in virtually every college, church, union, neighborhood, and in the army itself. There were later huge antiwar protests—involving half a million, a million people, demonstrating against the war. The already existing antiwar movement rapidly radicalized as a result of the Tet Offensive. It came to understand that the war was not a result of mistakes, which is what many people originally believed, or of government lies; the war was a consistent part and logical outcome of American foreign policy. Activists now understood that the United States was the occupying power, the colonial power in Vietnam, and that the resistance to the U.S. occupation on the part of the Vietnamese was legitimate; that this was an unjust colonial war on the part of the United States and a just war for national liberation on the part of the Vietnamese, no matter who was leading them. Whether it was the Communist Party leading them or not, they had the right to independence and self-determination. That’s something that became accepted throughout the antiwar movement in this country. By the way, this still is not accepted today in terms of Iraq—that the Iraqi people have a right to resist occupation; that occupation is not liberation; that the Iraqi people, no matter what their politics, have the right to their own self-determination; that they have just as much right to this as the American people do.

There began to be identification on the part of the antiwar movement with the victims of the occupation, with the Vietnamese. At demonstrations people were no longer just singing, “Give peace a chance,” but were now chanting, “The NLF will win.” Internationalism began to overcome American nationalism. Activists began to recognize that so-called national interests were the interests of our rulers, not of the American people. There was identification with the victims of American imperialism, and the idea that we want them, the other side, to win. Our government is the enemy, not the people over there. They have a right to their independence. That radicalized a whole generation in this country, the idea that every nation has a right to liberation, to self-determination to run its own affairs without some “humanitarian” intervention. (Invasions are always presented as being humanitarian.) Not that we are invading Iraq for oil; no, we’re there to bring democracy, or prevent civil war, or some other high-sounding imperialist party line that is presented to the American people to keep them passive and confused so the government can continue this war.

The mass opposition to the war, and the impact of the nature of the war they were fighting provided the context for a soldiers’ revolt inside the American army. It is difficult for people to understand that there was more opposition inside the American army to the war than there was on the college campuses. Most history books are written as if this was just a student movement, and hide the rebellion of the American soldiers. An organized and critically important opposition to the war existed inside the U.S Army. The head-fixing industry cannot tell you the truth, they cannot tell you that American troops were violently against the war and the officers that tried to lead them into battle, that within a few years of the Tet Offensive, a quarter of all the American troops in Vietnam deserted or went AWOL, that those that stayed refused to engage in combat; that they mutinied, and killed their officers in what was called “fragging.” A quarter of all the officers killed in Vietnam were killed by their own troops. There was an immense radicalization of the American army. There were dozens of antiwar groups and 300 underground antiwar newspapers inside the army.

And those newspapers presented a radical and socialist analysis of the war. This is from the Ft. Lewis Free Press: “In Vietnam the lifers, the brass, are the enemy, not the enemy,” or this from the Fort Ord Right-on Post: “We recognize the enemy. It’s the capitalists who see only profit. They control the military who send us off to die.” The American army collapsed in the three years after the Tet Offensive. The troops could no longer be used as a fighting force; they had to be brought home.

These three forces—the resistance of the Vietnamese, a mass antiwar movement, and a revolt inside the army—eventually ended the war in Vietnam.

Tet also had enormous impact internationally. The rest of the world became aware that the United States could not effectively act as world policeman—it was bogged down in Vietnam. No longer did the fear of American military force act as a decisive factor to maintain the status quo. The stability of existing institutions of Washington’s allies and clients were now called into question. People were no longer intimidated. The coming victory of the Vietnamese gave people throughout the world courage and hope. If the people of Vietnam, a very poor, economically underdeveloped country could defeat the U.S., then others could as well—if they had the courage, determination, patience, and organization of the Vietnamese.

Before getting into the French situation, I just want to discuss the other aspect of the radicalization here at home, and that is the impact of the Black liberation struggle on everyone in this country. It is the struggle for Black liberation that was the dynamic, the motor force of the whole radicalization of the 1960s; of the radical student movement, of the antiwar movement, and the movements that were to follow among women, gays, and other oppressed national groups. It was the mass base for change in this country, in the struggle, first for civil rights and then for Black liberation that changed everything that went on in the politics of the 1960s.

The struggle for civil rights started off as a nonviolent direct action movement and by 1965 it had won the end of legal segregation in the South, the end of segregation in public accommodations and in the schools, and the right to vote. It had been successful, but the South was now like the North. It was like the North and northern racism, the institutionalized racism of all the institutions of American society, of employment, housing, and schools still remained.

Northern liberalism was seen for what it was. And that was one of the things that radicalized people during Vietnam—the war was not conducted by right-wing Republicans, but by Kennedy and Johnson and the liberal Democrats. The notion that the election of a liberal Democrat would end the war was hardly realistic. The liberals were the people running the war. Similarly in terms of what was going on in the civil rights movement; when it shifted to the North, it shifted to northern cities that were run by liberal Democratic Party mayors. These cities were totally segregated not by law but de facto, by custom, and Blacks there faced enormous police brutality and deep poverty. This led, starting in 1965, to a series of ghetto uprisings—from 1965 to 1966 to 1967 to 1968. Every year, every summer, was called the “long hot summer,” because there were hundreds of uprisings in the Black working-class ghettos. Hundreds of thousands of people took part in them. Tens of thousands of people were arrested by the police in these uprisings. This is the only country that had hundreds of urban uprisings against oppression in the 1960s.

These rebellions radicalized the Black ghettos, leading to the call for Black power and for Black liberation. They led to the creation of large numbers of revolutionaries inside the ghettos—of people who thought you needed a revolution in this country to end racism. This radicalization led Martin Luther King, Jr. to reexamine his political strategy, and to shift dramatically to the left. He came out against the war in Vietnam at his famous April 1967 speech at Riverside Church in New York and he began to take part in organizing poor people and workers, saying that there could be no equality without economic equality. King was killed in Memphis, Tenn., where he was supporting a sanitation workers’ strike. One-hundred twenty-five ghetto uprisings took place in the days after he was murdered; 73,000 National Guard and army troops were called out to put them down—the largest use of military force in the United States since the Civil War. King’s death plus the ghetto uprisings shifted the movement from nonviolence to the creation of revolutionary organization inside the Black community, the most important of which was the League of Revolutionary Black Workers in Detroit, and, on a national basis, the Black Panther Party (BPP).

Hundreds of thousands of young Blacks identified with the BPP. Tens of thousands joined it in the next year or two, making it the first sizable revolutionary organization in this country since the start of the Cold War. The BPP had an enormous impact on radicals—convincing them that they should be doing something similar. The idea behind the BPP, however, was for a Third World revolution; that Blacks inside the United States represented a colony, and that the Panthers were part of the Third World liberation movement. The most important book on the left in 1967 was Régis Debray’s Revolution in the Revolution? that tried to sum up Che Guevara’s strategy, which was about guerrilla warfare based on the peasantry; that you really can’t have an urban working-class revolution. All the people inside the cities, including the workers, it argued, are totally contaminated and corrupted by city life, and the only revolution that can occur is through peasant guerrilla bases, foci, which will eventually take the cities.

All of this was to change in May of 1968 with what occurred in Paris. It did not just transform the French Left, it altered the international Left everywhere, including in the United States, where the 1960s student New Left finally had to confront the reality of class struggle.

Paris was not a planned revolt. It was a sudden, spontaneous explosion—which was started by students. It spread to young workers, and from young workers it spread to the working class as a whole. It began as a typical 1960s student struggle. After the Tet Offensive, students at Nanterre University outside of Paris, called demonstrations in support of the Vietnamese at various American targets in Paris, including the American Express office. It led to confrontations and clashes with the police. The police arrested a few students. Protests erupted demanding their release. The students called for days of struggle at Nanterre University. The head of the university shut the university down; the action then shifted to the Sorbonne University in Paris itself. When it did, the head of the university there, in typical 1960s fashion, called in the CRS—the widely hated and brutal French riot police.

At the Sorbonne, the police came in and started arresting and beating everyone in sight. The ferocity of the police attack created mass support for the radical students and their demands. The students then called for a student strike on May 6, 1968. The riot police were brought in again. They fought with the students; 422 students were arrested. There were lots of casualties. But what made this different from other student demonstrations up until then, was that the students, under socialist leadership, fought back and 345 police were injured. The confrontations had begun in October 1967 at Le Mans, where young workers from Renault and Schneider battled with the police, followed in January 1968 at Saviem Truck in Caen, with violent clashes between young workers and the police, and finally in March at Redon where similar fighting took place.

The day after the student strike, 30,000 students in Paris went into the streets chanting, “Power is in the streets” and singing the Internationale, the anthem of the socialist movement. Public opinion shifted sharply in favor of the students. The middle class in Paris was shocked by the police brutality against middle-class students that they had witnessed in the Latin Quarter and they became supportive of the students.

The attitude of workers was somewhat different. They were totally impressed by the fact that students, even middle-class students, had fought back, that it was possible to fight back and perhaps win, as the students seemed to have the authorities over a barrel. Young workers started to pour into the Latin Quarter to take part in these demonstrations. A few days later all of the radical groups at the Sorbonne held a joint meeting and decided to call for a mass demonstration demanding the release of everyone who had been arrested. “Free our comrades” was the main slogan, and it led to a demonstration on Friday, May 10. Tens of thousands marched through the Latin Quarter. The riot police were brought out again. In the clashes with the police, the students started to set up barricades, to show their determination not to retreat on their demands.

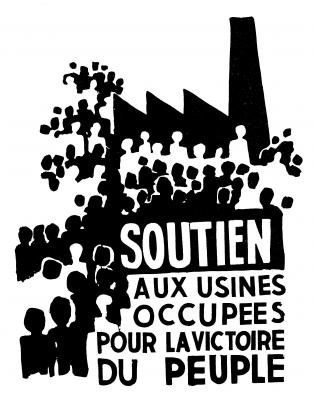

The setting up of barricades is part of the French revolutionary tradition, and a historic link to the heroic fight of Parisian workers in 1871, known as the Paris Commune. You set up barricades to hold off and fight the police…barricades made up of cars, trucks, trees—anything. Fifty barricades were built in the Latin Quarter, which the demonstrators renamed, The Quarter of the Heroic Vietnamese Fighters. The street cobblestones were broken up to throw at the police. May 10 was the Night of the Barricades, of huge fighting between the police and students and young workers, and it had a wonderful impact, because the radio stations broadcasted it live to millions of people who heard what was actually going on. It shocked the entire country, so much so that the next day, on Saturday morning, the trade unions called for a one-day general strike and mass demonstration on Monday, May 13, in support of the students. It was the largest demonstration in Paris since the liberation from the Nazis, as a million people took to the streets to defend the students against the police. The trade unions under the leadership of the Communist Party were chanting, “De Gaulle, goodbye” (he was the president of France), “Ten years is enough,” and the students were chanting “All power to the workers,” an omen of what was to come. This general strike and mass demonstration on May 13 marked the transition from a student uprising to a working-class revolt.

The next day in Nantes, at the Sud Aviation factory, where weekly symbolic strikes of fifteen minutes to protest the cut in hours and wages had been going on for months, young workers under Trotskyist and anarchist influence, refused to return to work after the fifteen-minute stoppage, and marched through the factory. They were feeling confident as a result of the biggest working-class demonstration since the liberation of France. They marched through the factory, gathering support, and then they rounded up the managers, locked them up, while 2,000 workers barricaded themselves inside the factory. So, a factory occupation was detonated by the militancy of the student struggle.

The next day at the Renault plant in Cleón the young workers did the exact same thing. They did so because this was a backward factory. Only a few of them had come out at the Monday demonstration. They felt ashamed and they thought they had to make up for their poor behavior, so they took all the factory managers, locked them up, and barricaded the factory. The next day the strike spread to all of the Renault plants, six in total. That night the main Renault plant at Boulogne-Billancourt, the largest factory in France, employing 35,000 people; the most militant, the most important factory in France—was occupied. The Communist Party (CP) attempted to stop the Boulogne-Billancourt occupation. The radical young workers, under the leadership of militants from the Trotskyist Lutte Ouvrière (Workers’ Fight) and the Maoists, pushed it through and the CP decided it was better to try to put itself at the head of the occupation than to continue opposition to it. The CP at that time was the main left-wing political group. It was a mass organization and controlled the leadership of many of the key trade unions.

The occupation of Boulogne-Billancourt was the turning point, the signal for the occupations to become general. The strike wave and factory occupations spread in the next few days to all of the important industrial plants in auto, steel, electric, chemical, and so on, first to all of the large factories, and the following week to all the small factories; then it spread to the offices, to the banks, to white-collar workers, to teachers, and so on. By the end of the following week 10 million people were out on strike and were occupying workplaces, in what was the largest general strike, the largest factory occupation, in history—and it was to go on until the middle of June.

The strikes led to a dramatic rise in working-class confidence and consciousness. The first night of the occupation of the Renault factory at Boulogne-Billancourt, the workers put up a large banner over the factory. It said, “For higher wages and better pensions.” The second day they took it down and they put up a new sign over the factory, which raised the traditional left-wing slogan, “For a Socialist Party-Communist Party-trade union government.” The third day they took it down and they put up another banner over the factory and it said, “For workers’ control of production.” In three days they had gone from higher wages to we should be running the show. There was this enormous leap in revolutionary consciousness. For the first time in twenty years, the working class was back as a revolutionary factor in politics, producing an enormous shift inside the Left; not just in France, but also in the United States and every place else. The idea revived that revolution is not just something that can happen in the Third World; it can also happen in the advanced capitalist industrialized countries, but only as a working-class socialist revolution. The radical Left began to argue that what was necessary was the organization of the working class for revolution.

And by the way, some of it went even beyond factory occupations. In a number of towns, in Nantes, Caen, St. Nazaire, and a few other places, the workers took over and ran things. In a few workplaces they continued production under workers’ control, in other places they took over the towns; that is, roadblocks were erected into the town, prices were put under housewives’ committees, and everything was occupied; the teachers ran day care centers for kids, and that sort of thing. But for the most part its feature was the factory occupations, which went on for three weeks.

After about ten days the trade unions negotiated a deal with the government. They came back with a proposal raising wages 10 percent for better paid workers and 35 percent for the most poorly paid workers, with all sorts of other concessions. It was turned down in all the factories—booed down, voted down. The occupations went on, but the Communist Party and the trade unions it controlled were able to take this, what was the largest general strike in world history and the largest factory occupation, and break it up into a series of local strikes, and to shift it into a call for support for the Left in parliamentary and congressional elections. The way to win was not to keep on occupying the factories, they argued, but was to vote for the Left in the elections, and bring communist ministers into a coalition government.

And so the Communist Party leadership was successful after a period of some weeks in, as I said, breaking the general strike up into a bunch of small local strikes, and then winding down each occupation, one by one. They demoralized and manipulated workers in one plant to end their occupation by telling them that other factories were going back to work—because they wanted people back to work before the elections actually took place. The truth of the matter was this strike went as far as it could possibly go so long as it was spontaneous and leaderless. There was no alternative leadership to the trade unions and the Communist Party. It went as far as it could and then it was over.

The general strike, factory occupations, and emergence of a large revolutionary Left opened up the question for the first time since the start of the Cold War of creating revolutionary parties. It is difficult for people today to fathom what the working-class Left was like then, because communist parties have pretty much disappeared as mass forces with the collapse Stalinism, but at that point in time the French CP was a mass party and the main Left group. As the French put it, you could do nothing without the Communist Party, and you could do nothing with the Communist Party. You could not make a revolution without the Communist Party, and you couldn’t make a revolution with them. The betrayal of the movement by the CP opened up an enormous new space to the left of the communist and social-democratic parties throughout the world. It raised the whole question of organization. Until 1968, there was an enormous hostility to revolutionary organizations within the New Left.

By the way, I didn’t really go through it, but many of the factory takeovers were due to the initiative of individuals and groups from small revolutionary organizations: Maoists, anarchists, and Trotskyists, or MAT as they were called in France. At the beginning of 1968, there was no revolutionary group in France that had more than 300 to 400 people. All of the groups were small, but people who belonged to them started many of the occupations. But you had a mass Communist Party of over 300,000 people. There was nothing else on the left big enough to counter it. Most people were hostile to revolutionary organization for reasons that are very similar to those that hold the Left back today. Middle-class liberals, social democrats, and anarchists say that revolutionary parties are mired in original sin, that they are by nature hierarchical, elitist, antidemocratic, and authoritarian—and that anyway there is no need for organization. As soon as the May events took place those ideas lost their mass appeal as their weaknesses became apparent. They were totally ineffective in producing revolutionary change, and serious militants quickly understood that you needed an alternative leadership to the Communist Party and, even more, a revolutionary organization capable of replacing the factory owners and their existing state, with its police, courts, and army. The strength and power of the working class is based upon its role in production, its collective nature, its collective actions, collective struggle, collective decision-making, which requires serious collective organization. If you were going to be successful, you needed a working-class, revolutionary party. There was a rush to join revolutionary organizations in France, in the U.S., in every country. In this country, some of it was exceedingly primitive. The broad left-wing organization Students for a Democratic Society, which finally started to move from social democratic and New Left hostility to theory and revolutionary ideas, was destroyed by it own leadership, which broke up into competing groups of self-proclaimed Maoist “vanguards,” all of whom were trying to smash and grab SDS for people for their own little sects.

But there was throughout the world a rush to try and fill this organizational vacuum on the left, because it was accepted that revolution was possible in the advanced world. For the next seven years there was a mass working-class upsurge in many countries and prerevolutionary situations in parts of southern Europe, and South America. These struggles raised questions in people’s minds about how do we actually win. How do we take power? You can’t win with some threadbare ideas replacing revolutionary theory. You can’t win without organization. How are you going to do that? For the next seven years there was an enormous struggle. There was an international working-class upsurge in many countries, with strikes, wildcat strikes, rank-and-file groups inside unions, factory occupations, workers’ councils, even workers’ control in some places. In two places the struggle reached its highest point—in Chile in 1973 and in Portugal in 1974 and 1975. In both places working-class revolutions developed but were eventually defeated.

Since the defeat of the revolutionary wave that began in 1968 and ran until 1975, we have had thirty years of reaction. One of the things that you’re told today is don’t be too radical, but the weakness of the Left of the 1960s was that it was not revolutionary enough, that it did not go all the way. When you engage in radical struggle, if you don’t win, there’s going to be an attempt to take everything back, and there was. In Chile and in Argentina, defeat led to military dictatorships, to the police going into the factories taking out the working-class vanguard and killing them to intimidate and destroy the workers’ movement. It other places it didn’t go that far, but what we got here and internationally were thirty years of reaction—of the free market, of neoliberalism, and of sharply increased inequality. We have had thirty years of an employers’ offensive, and all the reactionary politics tied up with it—opposition to abortion, to women’s liberation, to a woman’s right to control her body; and an attempt to push back all the gains of the civil rights movement, a union-busting attack on workers’ organizations and living standards.

A million Black men are in jail today, mostly on nonviolent drug charges. In terms of the criminal justice system things are more racist than they were under Jim Crow segregation. Wages have not risen (in real terms) since 1973. Students have it worse than when I went to school. The rulers of this country were able to win—and have introduced their entire reactionary program. For thirty years we’ve had to put up with it, but now things are starting to open up because they have another defeated war and they have an economic crisis on their hands that is the biggest thing in fifty to sixty years and they know it. This is not just a recession we are entering; but an enormous financial meltdown, and with it a crisis of the international capitalist system.

Years like 1968 come; 1968 was not the only revolutionary year. There was 1917. There was 1919. There was 1936. Those years come. The question is whether people are prepared for them; whether they are prepared for when the conditions for an explosion exist—and I will tell you I think the conditions for an explosion exist in this country. Lots of people think that everything is screwed up—everything. They don’t think that there’s anything they can do about it, they don’t know how you can change it, but they think that things are terrible, because they are terrible for them. Millions of people are losing their homes; millions of people will lose their jobs. As I said, there hasn’t been a wage increase in this country since 1973, even though the economy has tripled in size. The rich, the employers, have gotten everything.

The possibility for an explosion exists. That doesn’t mean it’s going to occur for some period of time. Yet for the first time in years you can see a thoroughgoing repudiation of the Right, and the promises that Clinton and Obama make are to appeal to the change in consciousness, the shift to the left, among working people. People are starting to have expectations that things will change. They hope that. We will see what happens when the Democrats come into power and how they actually handle the war and a serious recession, and what happens to peoples’ expectations, whether they go further, whether they radicalize more. We don’t know when an explosion will come, but eventually an explosion will come. In conditions that are miserable, where people are oppressed and exploited, there will be resistance. They will fight back, particularly when they think there’s any chance whatsoever of there being some success. And the question for all of us is, are we going to be ready for it?

All of us are called upon to make a decision. There’s nobody who can liberate you but yourself. The first thing you have to do is liberate yourself; liberate your mind. Decide that you will not put up with injustice, oppression, exploitation, and war, that you’re not going to go quietly being processed to put up with all they want you to accept. You have to know who you are, and which side are you on.

The second thing you have to know is that you cannot liberate yourself by yourself; you can only do it with other people. There’s no way to end your own oppression and exploitation without collective action, collective struggle, joining with other people to change this world. And so all of you have to start thinking through what that means; how you’re going to educate and train yourself to be effective movement organizers, to raise your own and other peoples’ consciousness, to create the sort of effective organization and leadership that can lead to a successful liberation. The lessons of 1968 are that we should be preparing now for the future explosion by building revolutionary working-class politics, leadership, and organization.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Google+

Google+ Tumblr

Tumblr Digg

Digg Reddit

Reddit StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon