The return of Keynes?

“Remember Friday March 14, 2008: it was the day the dream of global free-market capitalism died.”

—Martin Wolf

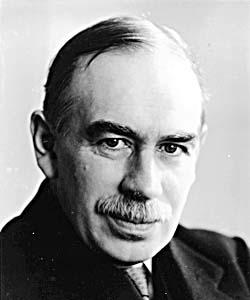

THE FIRST few decades of the post–Second World War era were a period of unprecedented economic boom for world capitalism. From the late 1940s through the early 1970s, the global economy expanded at a rate of 4 percent per year while the gross capital stock grew at 3.2 percent per year.1 During that time, the theories of British economist John Maynard Keynes—of deficit-based, government stimulus spending and strong regulation of markets—dominated economic policy and thought. Keynesianism became connected in popular consciousness with the idea that state intervention—including government social programs, infrastructural spending, and even in some cases, partial state ownership—was necessary to ward off the system’s tendency toward deep economic disturbances, such as the Great Depression of the 1930s.

However, by the 1970s, the long boom was coming to an end. In 1965, persistent inflation set in among the advanced capitalist nations. At the same time, U.S. profit rates began to fall precipitously as the U.S.—burdened by high military spending and aging capital stock—became less competitive on the world market against the freshly rebuilt and retooled economic powers in Europe and Japan. This produced a period of low growth and high inflation—dubbed “stagflation.” For this, Keynesian theory—which in itself calls for inflationary policies during times of recession—had no answer. Further encouraging inflation during an already inflationary period was not an option. This left economic policy makers at a loss and helped open the door for a radical change in approach.

Out of the crisis emerged a hitherto obscure group of academics centered around the Austrian economist Friedrich Von Hayek, a group that included Ludwig Von Mises and Milton Friedman, who had been arguing since the 1940s against state intervention in the economy, against unions, and against the welfare state.

Milton Friedman and his acolytes, many trained at the University of Chicago, along with influential think tanks like the Cato Institute, provided the ideological justification for an all-out attack on working-class wages and standards of living, coupled with proposals to deregulate the economy, privatize public enterprises, and dismantle the social safety net. These conservatives, later dubbed “neoliberals,” argued that the best way to stimulate demand was by steering money directly to capitalists by cutting wages and taxes. This was known as “supply-side” economics, as opposed to the “demand”-oriented policies of Keynesianism. This was the dominant economic theory for the past thirty years.

The neoliberal period witnessed three waves of significant expansion in which the U.S. was able to reassert its dominance in the world market—though the U.S. was never to re-create the robust growth rates of the postwar boom. However, the policy of rampant deregulation that has been the hallmark of this era led to severe economic crisis, starting with the Asian crisis in 1998, spreading to Latin America, and finally producing a sharp recession in the U.S. in 2001 with the collapse of the dot-com bubble. The recovery that followed, based on a grossly inflated housing bubble backed by subprime mortgages, has led to a massive destabilization of the financial system, which remains crippled by the credit crunch that initially emerged in 2007, and that continues to rip through the U.S. and world economy with no end in sight.

Rather than “letting the market work,” the government has been increasingly aggressive in trying to stabilize the financial system. The state and central banks in the U.S. and Europe also have intervened heavily in trying to stabilize the financial system—including partial and temporary nationalizations—violating a key precept of neoliberalism that state intervention is harmful to the economy. Many trillions of dollars have already been spent by states to calm the financial panic. The crisis, itself a product of neoliberal deregulation, has forced a break from the policies and ideology of the past three decades.

These failures of the free market have raised the question of what economic paradigm will replace neoliberalism. In recent months, a flurry of articles and books have appeared making the case for a return to Keynesian measures. Naomi Klein’s Shock Doctrine, a blistering indictment of neoliberalism, suggests Keynesianism was both less brutal and provided more robust economic growth. She writes of “Keynesian attempts to pool collective wealth and to build more just societies.”2 Meanwhile, left-wing economic journal Dollars & Sense recently argued for the re-creation of the New Deal–era Works Progress Administration.3 The Nation, under a headline, “Toward a new New Deal,” raised that prospect with a dozen people, including Howard Zinn, Andy Stern and Jesse Jackson.4

In the mainstream, Paul Krugman, a prominent New York Times columnist and the 2008 Nobel Prize winner in economics, consistently argues for Keynesian solutions to the current economic problems. One of his recent articles, written not long after Barack Obama’s election as forty-fourth president, entitled “Franklin Delano Obama,” argues that this moment provides an opportunity for Obama to engage in the kind of government stimulus and regulation used in the 1930s to attempt to stabilize capitalism. Some magazines have taken that one step further, inserting Obama’s face into iconic images of FDR. Even uber-capitalists Bill Gates and George Soros have come out recently arguing for a kinder, gentler capitalism by limiting wealth disparities and for more government oversight of the economy and the financial system.

Economists are calling this the worst crisis since the 1930s. It is only natural then, that the economist most associated with attempting to devise mechanisms to alleviate that crisis and prevent more from arising should now be on so many people’s lips. All this raises some important questions. One, what exactly is Keynesianism? Secondly, was Keynesianism ultimately responsible for the long postwar economic boom? Lastly, would a return to Keynesianism be possible?

The rise of Keynesianism

Before the advent of neoliberal economics, Keynesianism was the dominant ideology taught in economics classes and was the de facto starting point of economic policy after the Second World War. “Thanks to this new economics, it was widely accepted that given an appropriate manipulation of the budgetary aggregates and suitable monetary policies,” to quote one study of Keynesianism from the 1980s, “what Keynes was to term the level of effective demand could be raised to a point where all involuntary unemployment was more or less eliminated.”5 This was a period in which state intervention in general was seen as normal and necessary to the functioning of capitalism. Indeed, there developed in this period a whole spectrum of acceptable state monopoly capitalist measures, depending on the country, ranging from deficit spending policies to what was called the “mixed economy”—a mix of private and state ownership, and extending all the way to complete state ownership. These policies were adopted in various ways by states regardless of where they fell on the political spectrum.

The roots of Keynesianism lie in the Great Depression of the 1930s. That deep crisis of capitalism—marked by a collapse of production and world trade and high rates of unemployment throughout the advanced capitalist countries—gripped the advanced nations for nearly a decade. It contributed to deep social unrest, as there seemed to be no end to the misery of the masses. At the depths of the crisis in the U.S. it is estimated that the unemployment rate reached close to 25 percent.

Prior to the depression, bourgeois economics accepted the theory that all markets are self-regulating and self-correcting. With the rise of the labor movement, mainstream economists came to reject the labor theory of value—accepted by the classical economists such as Ricardo and, to a certain extent, Adam Smith—which posited that value is determined by the labor embodied in commodities. Interpretations of the labor theory of value varied, but it was accepted that value was created in the production process by living labor. However, acceptance of the importance of labor within mainstream thought had the unfortunate effect—from the capitalist point of view—of giving weight to the conception of surplus value as “unpaid labor,” and of the working class as central to the system’s functioning and, ultimately, as the class with the power to overthrow it. Instead, bourgeois economists, whose concern became that of defending the economic order of capitalism, devised alternate explanations that substituted for the labor theory of value with other, more superficial, and therefore less threatening theories.

One of the main tenets of what Marx called the “vulgar economists”—apologists for the system—was Say’s Law (named after the late seventeenth and early eighteenth-century economist J.B. Say), which became the dominant view prior to the 1930s. Say’s Law posited that production generated its own demand. Essentially, the view of economists was that one person’s spending becomes another’s income. This means there is a “circular flow of income and output” through an economy. Overproduction or shortages could therefore only ever be short-term, accidental phenomena. As a result, the state need and should do nothing to try and solve recession, but merely wait for the system to fix itself. This became the prevailing free-market theory accepted by the “neoclassical school.” However, the severity and the seeming intractability of the Great Depression opened the door for a revision in economic thought.

John Maynard Keynes was a British economist who lived from 1883 to 1946. He was a prodigious writer whose most influential work was the General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, published in 1936, although he was well known since at least the 1920s. The book hit the scene at the height of the Great Depression. It raised major arguments against the dominant economic ideology of the time. And its last section is devoted to laying out a series of public policy prescriptions for ending crisis.6

From the capitalist perspective, Keynesian theory came along at the perfect time—providing a ruling-class strategy to solve the crisis at a time when millions of people around the globe were drawing revolutionary conclusions. As Marxist economist Paul Mattick wrote:

[T]he great economic and social upheavals of twentieth century capitalism destroyed confidence in laissez-faire’s validity. Marx’s critique of bourgeois society and its economy could no longer be ignored. The overproduction of capital with its declining profitability, lack of investments, overproduction of commodities and growing unemployment, all predicted by Marx, was the undeniable reality and the obvious cause of the political upheavals of the time. To see these events as temporary dislocations that soon would dissolve themselves in an upward turn of capital production did not eliminate the urgent need for state interventions to reduce the depth of the depression and to secure some measure of social stability. Keynes’ theory fitted this situation. It acknowledged Marx’s economic predictions without acknowledging Marx himself, and represented, in its essentials and in bourgeois terms, a kind of weaker repetition of the Marxian critique; and, its purpose was to arrest capitalism’s decline and prevent its possible collapse.7

Despite the flaws Keynes saw in the system he still unreservedly favored capitalism and was in support of the “inequality of the distribution of wealth” as the best means for a vast amassing of capital. “The immense accumulations of fixed capital which, to the great benefit of mankind,” he wrote in the Economic Consequences of the Peace, “were built up during the half century before the war, could never have come about in a society where wealth was divided equitably.”8 Ultimately, Keynes sought not to replace capitalism but to regulate the system’s functioning without sacrificing its fundamental characteristics. Keynes himself was quite conscious of the necessity of both theoretical and practical measures to save capitalism and combat revolutionary ideologies. In a letter to Franklin Roosevelt in 1933, after the adoption of the first New Deal policies, Keynes called Roosevelt “the trustee for those in every country who seek to mend the evils of our condition by reasoned experiment within the framework of the existing social system. If you fail, rational change will be gravely prejudiced throughout the world, leaving orthodoxy and revolution to fight it out.”9

Keynes was not the first mainstream critic of free-market capitalist ideology. But his ideas caught fire because they provided a more cogent explanation for the Great Depression than his neoclassical predecessors. At its heart, Keynesianism looks at crises within capitalism as arising from “underconsumption.” That is, the problem is not that of overproduction in terms of what can be sold profitably—but that of consumers, for one reason or another, backing off and not consuming enough to stimulate investment.

Keynes argued that not all savings are automatically converted into spending in a short time span. That serves as a drain on Say’s seemingly perfect cycle. And, in recessionary situations, capitalists may fear investing if they cannot find a profitable outlet. Instead, they hoard it and the rate of savings increases. The lack of investment means layoffs and scaling back in production. This only exacerbates the crisis. Left to its own devices, he argued, capitalism would fall into deep crises repeatedly. The policies he put forth purported to be a way out of the Great Depression through a path of fiscal and monetary policy and aggressive government intervention.

Economic activity according to Keynes is determined by what he called “aggregate demand.” In times of recession and overproduction, for capitalists to hoard savings and push through layoffs and wage cuts was exactly the wrong strategy. In turn, workers, in a suddenly precarious state, also tend to cut back on spending and try to save what they can in the event that they might lose their jobs. The net result of all of this is that consumption of goods throughout society continues to slow down, which only exacerbates the existing crisis of overproduction. That, in turn, can lead to even more hoarding by capitalists in a vicious circle.

The solution was for the government to play an active role in the economy, first by manipulating interest rates to moderate inflation or deflation, and secondly by “priming the pump” by undertaking strategies to increase “effective demand.” In chapter ten of The General Theory, he gives what is now a famous hypothetical case of pump-priming, suggesting that unemployment could be eliminated by the government “filling old bottles with banknotes,” burying them in disused coal mines, and leaving it “to private enterprise…to dig the notes up again…. It would, indeed, be more sensible to build houses and the like; but if there are political and practical difficulties in the way of this, the above would be better than nothing.10

As Mattick wrote:

In this view, it is the function of government to secure the existence and welfare of private enterprise. Aside from the overall effect of governmental money and fiscal policies, depressed industries are to be helped along with special credit facilities. Public works are to be constructed with an eye to the needs of private capital—roads for the automobile industry, airports for the aircraft industry, and so forth. Along with preferential treatment for new investments there should also go an increase in the propensity to consume by way of social security legislation as an instrument of economic stability.11

Why focus on demand rather than tax cuts or other packages aimed at placing funds directly in the hands of investors? Keynes agreed that increasing the rate of investment could achieve the aim of increasing consumption within society. However, he also saw that as corporations and the wealthy accumulate more wealth, they tend to invest an increasingly smaller portion of their savings. This “liquidity preference,” he argued, was a result of expectations of declining rates of return. Capitalists can be encouraged to invest, but not fully. Overall, “savings will increase faster than investments. As this occurs, aggregate demand declines and the actual level of employment falls short of the available labor supply.”12 Therefore measures to increase demand were more likely to stimulate investment than measures putting cash directly into investors’ hands.

Keynes was clear that his analysis was aimed at saving capitalism, not undermining it. “Whilst, therefore, the enlargement of the functions of government, involved in the task of adjusting to one another the propensity to consume and the inducement to invest, would seem to a nineteenth-century publicist or to a contemporary American financier to be a terrific encroachment on individualism,” he wrote. “I defend it, on the contrary, both as the only practicable means of avoiding the destruction of existing economic forms in their entirety and as the condition of the successful functioning of individual initiative.”13

It wasn’t only his desire to restore the health of capitalism that set Keynes apart from Marx. His theory of crisis was also fundamentally different. Where Marx saw the driving force of capitalism as accumulation for accumulation’s sake—the constant drive toward profit—Keynes continued to assume that “consumption…is the sole end and object of all economic activity.”14 The lack of “effective demand” in Keynes’ theory of crises is another way of saying that capital is not being invested; it does not, however, explain why. In short, whereas for Marx the possibility of the separation of purchase and sale that makes crisis a possibility is the starting point for understanding capitalist crisis, for Keynes it is the endpoint. Keynes’ theory of crisis—the lack of aggregate demand—is merely a description of the effects of crisis, not an explanation of why crises take place.

Marxist theory roots economic crisis in a crisis of profitability, which is the key factor in determining levels of investment. The unplanned nature of capitalist expansion leads to the development of disproportionalities between various branches of production, overproduction of capital, and the production of too many commodities that can be sold at a profit. The expansion of credit facilitates the expansion of investment and of the market, only to contract it when investment has overshot what the market is capable of absorbing—a reflection of the anarchy of the market. The inability to sell means capitalists cannot turn surplus value they have extracted from workers into profit, which leads to cuts in investments, layoffs, etc. This is one aspect of the system’s cyclical crisis. The incentive to incessantly increase productivity—something that competition compels each capitalist to do—leads to a growing ratio of investment in means of production over labor—that is, more investment in machines, in fixed capital in proportion to the number of workers employed. Since labor—as the source of surplus value—is the root of profits, the relative decline in the labor component of total investment leads to a decline in the rate of profit. Marx called this the tendency of the rate of profit to fall.

These factors lead to periods of crisis—recessions or depressions—that are only resolved through the destruction and devaluation of capital and mass unemployment and wage cuts. As Marx writes in Volume Three of Capital:

How is this conflict settled and the conditions restored which correspond to the “sound” operation of capitalist production? The mode of settlement is already indicated in the very emergence of the conflict whose settlement is under discussion. It implies the withdrawal and even the partial destruction of capital amounting to the full value of additional capital DC, or at least a part of it. Although, as the description of this conflict shows, the loss is by no means equally distributed among individual capitals, its distribution being rather decided through a competitive struggle in which the loss is distributed in very different proportions and forms, depending on special advantages or previously captured positions, so that one capital is left unused, another is destroyed, and a third suffers but a relative loss, or is just temporarily depreciated, etc.15

The problem with an underconsumptionist theory of crisis is that it cannot explain why crisis would not be permanent under capitalism, which it clearly is not. Underconsumption theory argues that the cause of crisis is that the working class does not consume the full value of its product. Naturally, the working class cannot consume the total product of its labor because, firstly, it does not consume means of production—machinery, raw materials, and physical plant. Secondly, it cannot do so because the basis of capitalist accumulation is the appropriation of unpaid labor. The restricted consumption of the working class is thus a condition of capital accumulation. True, Marx identified one contradiction of capitalism as that between the system’s constant drive for expansion and the “narrow basis on which the conditions of consumption rest.”16 However, he did not consider this to be the cause of crises:

It is a pure tautology to say that crises are provoked by a lack of effective demand or effective consumption. The capitalist system does not recognize any forms of consumer other than those who can pay, if we exclude the consumption of paupers and swindlers. The fact that commodities are unsaleable means no more than that no effective buyers have been found for them, i.e., no consumers (no matter whether the commodities are ultimately sold to meet the needs of productive or individual consumption). If the attempt is made to give this tautology the semblance of greater profundity, by the statement that the working class receives too small a portion of its own product, and that the evil would be remedied if it received a bigger share, i.e., if its wages rose, we need only note that crises are always prepared by a period in which wages generally rise, and the working class actually does receive a greater share in the part of the annual product destined for consumption. From the standpoint of these advocates of sound and “simple” (!) common sense, such periods should rather avert the crisis.17

Engels notes in Anti-Dühring that it is impossible to explain the cause of capitalist crisis by something that predated capitalism by centuries:

The under-consumption of the masses, the restriction of the consumption of the masses to what is necessary for their maintenance and reproduction, is not a new phenomenon. It has existed as long as there have been exploiting and exploited classes. … Therefore, while under-consumption has been a constant feature in history for thousands of years, the general shrinkage of the market which breaks out in crises as the result of a surplus of production is a phenomenon only of the last fifty years…. The under-consumption of the masses is a necessary condition of all forms of society based on exploitation, consequently also of the capitalist form; but it is the capitalist form of production which first gives rise to crises. The under-consumption of the masses is therefore also a prerequisite condition of crises, and plays in them a role which has long been recognised. But it tells us just as little why crises exist today as why they did not exist before.18

Keynesianism and the working class

According to neoclassical thought, unemployment was not a fault of the system, but was to be blamed on workers unwilling to accept wage cuts. In fact, neoclassical economists viewed wage cuts as being the solution to unemployment. Neoclassical economics also argued, again because of Say’s Law, there was no such thing as involuntary unemployment. “General unemployment appears when asking too much is a general phenomenon. … [Workers] should learn to submit to declines in money-income without squealing.”19

Keynes, however, argued that lowering wages in some instances might reduce effective demand. Cutting wages during a recession or depression would only exacerbate the crisis. Reducing wages could cut demand, meaning producers would have to reduce production. That could mean more unemployment and further worsen a recession.

The appeal for some, then, of Keynesian policy is that it calls for some redistribution of wealth from the top to the bottom, and that he pushes for “full employment.” However, Keynes’ perspective on this was strictly a ruling-class one. He supported not higher wages, but rather “the maintenance of a stable general level of money-wages” in order to maintain “equilibrium.”20 Keynes also thought it important that wages not become too high. In fact, though Keynes criticized the neoclassical theory of wages, he did not completely reject its premises, writing, for example, that, “A reduction in money-wages is quite capable in certain circumstances of affording a stimulus to output, as the classical theory supposes.”21

To that end, Keynes saw that inflation could be a positive tool for capital in that it could bring out reductions in workers’ wages without outright wage cuts. “A movement by employers to revise money-wage bargains downward will be much more strongly resisted than a gradual and automatic lowering of real wages as a result of rising prices,” he advised.22

Keynes’ concern that wages not be cut too much did not arise from a position of sympathy with the working class. Instead, it arose entirely from his underconsumptionist framework. In Keynes’ view, the key is for aggregate demand to equal total income and therefore ensure that an economy remains in balance. Therefore full employment should be pursued as a way to help stimulate aggregate demand when necessary. For Keynes, the best course of action is to “promote investments and, at the same time, to promote consumption, not merely to the level which, with the existing propensity to consume, would correspond to the increased investment, but to a higher level still.”23

For Keynes, wage reductions should not be viewed as a goal. In fact, governments should put in protections—minimum wage laws, for example—to keep a certain level of equity in the economy. This wasn’t because Keynes believed in equitable division in assets. Instead, he understood that great wealth inequalities could lead to resistance, and he considered it desirable to damp down class struggle.

Fiscal vs. monetary policy

Keynes viewed interest rates in a novel light as well. He saw interest as the cost of keeping wealth in the form of money. Interest is paid on money that is lent. So if a capitalist wants liquidity—that is, to keep cash on hand—he forfeits the interest he could receive if he had lent that money.

Keynes did share the neoclassical view that capitalists will make decisions on whether to lend or invest based on where the highest returns exist. If central banks move interest rates higher than expected returns on investment, capitalists will save money. However, if central banks lower interest rates, it can encourage capitalists to invest rather than save. Further, it might encourage them to borrow as well. The theory, then, is that by moving interest rates up or down, the state can influence decisions of whether capitalists invest or lend capital, therefore “heating” or “cooling” the economy.

Keynes also had concerns about the role that interest rates could play in causing excessive inflation or deflation. If investments exceed savings, inflation could occur and if the reverse were true, deflation could occur. That meant controlling interest rates is equally a tool for combating inflation. Economic well-being depends, then, on holding interest rates at a level that keeps savings and investments in line and thus helps stabilize prices. That model remains the key to central bank policy today.

What Keynes added to this understanding was that at times, capitalists might view all other options as money-losing prospects and no matter how low the state moved interest rates, capitalists may still save. Keynes called this a “liquidity trap” and this is exactly the scenario that befell Japanese capitalism in the 1990s. For this reason, Keynes saw manipulating interest rates as only one tool for encouraging investment.

The theory is that interest rates can be used to stimulate investment if real interest rates—that is interest rates adjusted for inflation—are cut to a point that they are negative. However, the Japanese experience illustrates that even if interest rates are negative, capitalists won’t invest if there is not a perceived avenue for investment. A similar dynamic is currently playing out within the U.S. economy. Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke has reduced the target for the Federal Funds rate from 5.25 percent to 1 percent. This has failed to induce lending or investment because there is little for capitalists to invest in that is profitable. Furthermore, central banks only have control of the economic policies within their own countries. It makes the system unstable, because central banks can end up working at cross purposes based on national needs as opposed to having a cohesive view of fiscal policy within the global economy as a whole.

This is why Keynes thought that monetary policy alone was not sufficient for encouraging or discouraging investment. The state itself needed to intervene through fiscal policy. The practical implications flowing from these arguments for Keynes were that the key to driving and sustaining economic growth was stimulating demand. That could be done in a myriad of ways, including, importantly, government fiscal policies intervening into the economy through tax rates, social security, and unemployment benefits, and spending on infrastructure and government services to create jobs.

Keynes conceptualized something called the “multiplier” effect. That is, by pumping $100 into the system at the right place, it could generate significantly more activity. Giving $100 to a worker might mean they immediately spend it at the local grocer. The grocer might then turn around and spend $90 of it himself on something else and so on and so on. On the flip side, giving $100 to a billionaire might not accomplish the same thing because the billionaire has no immediate need for the $100 and is only to going to spend if he sees investment opportunities with high rates of return.

Neoliberal ideology, for its part, rejects the role of fiscal stimulus and puts greater emphasis on monetary policy, which accounts for the predominant role of the Federal Reserve Bank over the past thirty years in dealing with economic problems. In practice, however, neoliberals do have a fiscal policy—cutting taxes on the rich and increasing defense spending. As a result, during the neoliberal era government spending as a percent of GDP and per capita has risen, not fallen. Theoretically, neoliberalism is opposed to state intervention. In practice, military spending and corporate welfare are not only accepted but welcome. Now that the system is in crisis, ideology is discarded, and those who may have crowed loudest for the state to leave the market alone demand that the state intervene to save it.

Prior to Keynes, governments generally viewed balanced budgets as the ideal. Keynes concluded that balancing the budget wasn’t inherently good or bad. Governments should base spending decisions instead on how they wanted to influence aggregate demand within their economies. Keynes understood deficits were inflationary and surpluses deflationary. His point of view was that in a crisis, you used a deficit to spur growth and to overcome deflationary tendencies. When growth was restored, you don’t just balance budgets, you then pay off the debt built up in the crisis.

Keynes and imperialism

One of Keynes’ lasting contributions is his role as one of the main architects of the international financial infrastructure of the postwar world. Keynes was a pivotal player at the international conference in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, in July 1944, at which the advanced capitalist nations formed the institutions that would dominate the postwar era. Emerging from the war as the leading military and industrial power, the United States set out to organize the capitalist world economically (through the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, and, in 1946, General Agreement on Tarrifs and Trade, the progenitor to the World Trade Organization) as well as militarily (through the North Atlantic Treaty Organization). “Leadership toward a new system of international relationships in trade and other economic affairs will devolve largely upon the United States because of our great economic strength,” wrote Secretary of State Cordell Hull during the war. “We should assume this leadership, and the responsibility that goes with it, primarily for reasons of pure national self-interest.”24 What were those interests?

Among the aims of the Bretton Woods meetings was to create institutions that could stave off a return of the Great Depression—a major fear at the time. It was also to rebuild capitalism itself in Europe in such a way as to open it—and the rest of the world that the European powers and Japan had dominated through exclusive trade blocs—to an expansion of U.S. trade and investment.

A key linchpin in this agenda was the dollar policy. Coming out of Bretton Woods every currency was pegged to the dollar, which, in turn, was pegged to gold. The fixed exchange rate put a dollar at $35 for an ounce of gold. Currencies would move against the dollar based on whether individual nations had balance of payments problems. If you had a deficit, you had to cut imports or else be forced to devalue. This arrangement more or less held until 1971 when the United States pulled the plug on the gold standard.

At the meetings themselves, Keynes represented British interests and in an attempt to establish Britain as a key junior partner with the United States. However, Britain was simply too weak to play that role. Keynes, for example, called for an International Clearing Union, a new international form of money called the “bancor,” and wanted lending rules that were tilted more toward Britain’s interest. He didn’t exactly get his way. Nevertheless, the institutions that emerged were fundamentally Keynesian institutions designed to play the same stabilizing and stimulus roles in the global economy that governments and central banks played in national economies.

The Bretton Woods institutions eventually took on much broader mandates than rebuilding capitalism in Europe and Asia, and after the crisis of the 1970s, adopted neoliberal loan conditions requiring nations to privatize and deregulate their economies. As Joel Geier writes,

Under the original Bretton Woods system, IMF loans were aimed at preventing devaluation and propping up demand. U.S. capital accepted these Keynesian measures when the U.S. was the major world exporter, ran large trade surpluses, and the rest of the world depended on its currency to pay for those imports. But in the 1980s, the IMF turned all of its previous policies on their heads: It now deliberately imposed devaluation and forced reductions in national income and demand in order to limit imports—all as a means to guarantee repayment of debt to international finance capital.25

The point is that whether in their Keynesian or neoliberal phase, these institutions were created to serve the interests of the dominant world powers, chiefly the United States.

Did Keynesianism work?

In theory, Keynesian policies seemed a plausible strategy, especially at a time when nothing else seemed to be working. Yet the first doses of Keynesian-type measures applied in the U.S. in the 1930s, while they had an impact on employment, failed to bring the U.S. out of its slump. Keynes’ explanation was that “the medicine he recommended was too niggardly applied.”26 This was at the height of President Roosevelt’s heralded New Deal agenda that included farm bills, the National Industrial Recovery Act, the Public Works Administration, the Works Progress Administration, the Wagner Act, the Social Security Act, and other measures all aimed at generating employment, investment, and, ultimately, economic growth. The Great Depression played out in two acts. There was an initial drop to the depths in 1932, a recovery from 1933 to 1936, and then a second drop in 1937 and 1938, even after the initial Keynesian salves had been applied. The economy only decisively recovered in 1939, when the United States began war production for the Allies.

Unemployment in the United States initially peaked at 25 percent in 1933, dropping to 14 percent by 1936. By 1938, it had climbed back up to 19 percent. In terms of industrial production, on an index with 1935–1939 equaling 100, as of 1929, industrial production was at 110. In 1932 it had dropped to 58. By 1937 it had climbed back to 113. But in 1938 it dropped again to 88.27 National income amounted to $82 billion in 1929. It dropped to $40 billion in 1932. It recovered to $71 billion in 1937, but dropped to $64 billion in 1938.28

The war effort created the rise in effective demand—in reality, government war spending, not consumer demand—that Keynesian measures failed to produce. As a result, employment and production, especially of arms, helped stimulate economic growth and an end of the Depression. Keynes himself saw the stimulating effects of the war effort as a vindication of his theories, having commented before the outbreak of war, “It is, it seems, politically impossible for a capitalist democracy to organize expenditure on the scale necessary to make the grand experiment that would prove my case—except in war conditions.”29 Of course, the cost of this method of recovery—fifty-five million dead—was a brutal price to pay. Moreover, the war played an important role in helping to wipe out and devalue capital and drastically reduce wages, both of which contributed to the restoration of profit rates after the war, but which were not part of Keynes’ remedies for crisis.

Moreover, in adopting these state-led measures, nations were simply returning to the same policies of “war socialism”—“forced savings, controls on money, credit, prices and labor, priorities, rationing, government-borrowings”—that they had put in place during World War I, “despite the ‘orthodox’ approach to economics that prevailed at that time.”30 It was a sleight of hand for Keynes to now promote war—a product of the unplanned, competitive character of the world system—as proof of his theories. As Mattick notes, “The purpose and meaning of Keynes’ theory was: to provide a way to have full employment in the absence of war or prosperity; and to overcome depression not in the orthodox fashions of waging war or passively awaiting the destructive results of the crisis, but through the new and ‘rational’ method of government-induced demand.”31

Keynes’ major contribution to the war was his suggestion to fund efforts through the sale of war bonds. Keynes feared the postwar situation might mean a return to the same demand problems and high unemployment levels that marked the Great Depression. Sales of war bonds would give workers a claim to future funds, which would help stimulate economic activity when the bonds were paid back after the war.

In the end, capitalism did not need this sort of stimulus. The project of rebuilding huge swathes of Europe and Asia provided a massive stimulus for economic growth that lasted for years. The destruction of capital and the cheapening of labor produced a massive stimulus after the war. The U.S. emerged with a project to use its advanced means of production to gain access to markets across the world. At the same time, the rebuilding efforts led to high employment.

Yet there was never a point, except during the war itself, where the United States, or any European country, reached full employment.32 Though the term full employment was thrown around, in practice it was adjusted to mean, in the words of the American Economic Association in a 1950 report, the “absence of mass unemployment.” Proceedings of the British Royal Institute for International Affairs in 1946 defined full employment as “avoiding that level of unemployment, whatever it may happen to be, which there is good reason to fear may provoke an inconvenient restlessness among the electorate.”33

The long boom was in part sustained by a form of Keynesian economics, only not as Keynes himself had envisioned it. The United States did organize expenditures on a massive scale that both stimulated demand but also helped prevent an overproduction of capital. This was in the form of arms spending, or what some termed the “permanent arms economy.”34 Prior to World War II, peacetime military spending never rose above 1 percent of GDP. In the 1950s, at the height of the Cold War, it averaged 7 to 10 percent, and for the entire period from the 1940s until the 1990s it averaged between 4 and 14 percent of GDP. Overall, $4.5 trillion was spent on defense in the forty-seven years after the end of World War II. “It was by way of inflation, debt accumulation, government-induced production, war preparation, and actual warfare that the dominant capitalist nations reached an approximation of full employment,” writes Mattick. “This experience strengthened Keynesianism and led to the widespread belief that a government-maintained ‘quasi-boom’ could be indefinitely continued.”35

It was only well into the 1960s that they started to face competitive pressures that unearthed the contradictions. The U.S. was spending huge sums on its arms industry while its most dynamic competitors—Germany and Japan—were reinvesting in new plant and equipment. Those competitors began to outpace the U.S. in the 1970s. In order to retain economic power, the U.S. needed to lower its labor costs relative to Japan and Germany, a difficult task especially important given that it was saddled with heavy arms expenditures when those nations were not. It was this crisis, in which stagnation was accompanied by inflation, that ultimately paved the way for the neoliberal restructuring of capitalism.

The return of Keynesianism?

In practice, neoliberalism did not produce a full break from Keynesianism; and in some important respects the limitations of a return to full Keynesian economic policy are already clear. First of all, interest rate reductions—the first line of defense recommended by Keynes—have already been used under the Fed chair Alan Greenspan (when the economy was in boom) and now by Ben Bernanke (in response to the financial crisis). In the first instance, easy money helped create the housing bubble that formed the basis of the current crisis; and the more recent cuts aimed at lifting the financial crisis have not unfrozen bank lending. Second, the government has already run up large deficits for the past two decades—the federal debt now stands at $10.6 trillion, and the current deficit is set to go up to a $1 trillion next year as new stimulus plans are brought on line.36 The question is how far can this go? The government can print more money, as it has already begun to do now that the dollar has rebounded; but there is a long-term danger of runaway inflation, which could force them to raise interest rates that put a halt to growth.

Under neoliberalism, Keynesian spending was replaced with the explosion of personal debt to sustain consumption. That was accompanied by a program of tax cuts to the rich and the gutting of government services and payrolls. However, as has become abundantly clear today, the debt at some point needs to be paid back or written off at a huge loss. The high levels of consumer, corporate, and government debt now pose a problem for the system that must be resolved before a growth cycle can resume.

Moreover, it’s unclear whether Keynesian deficits would serve their role. Deficit spending failed to pull Japan, for example, out of its malaise. There’s an association between the postwar boom and Keynesianism. But it’s demonstrable that, in fact, the growth originated not in Keynesian policy, but from other factors, namely the world war and permanent arms spending. Yet arms spending, which at one time helped slow growth rates and prolong the boom, is now one of the exacerbating factors in the crisis.

Certainly, the scale of the crisis has already and will continue to necessitate large-scale state intervention to try and shore up the system. Taxpayers in the U.S. are already on the hook for more than $7.5 trillion to save the banks.37 How successful these measures will be in preventing a worsening recession, if not a depression, is unclear.

The other problem is that this is a world crisis. No single state can therefore intervene to solve it, and yet the world’s national ruling classes, whom Marx famously called a “band of hostile brothers,” develop policies in their own national interests which can exacerbate the crisis. The individual actions of states can have a mitigating effect on the crisis, and can even alter its form, but they cannot prevent or eliminate them.

Reform and revolution

Keynes, while a critic of neoclassical economics, was no Karl Marx. He “never gave up the idea that capitalism was the best of all possible modes of production.... Keynes championed government intervention in capitalism because he believed that without it, the system he preferred would collapse into economic and political chaos. In other words, Keynes wanted to save capitalism from itself.”38 Keynes provided an explanation for why neoclassical capitalism had failed and purported to provide a road map for a way to reform and stabilize the system rather than scuttle it—at a time when many believed the system had demonstrated its bankruptcy.

Neoliberalism and Keynesianism are alternative capitalist strategies. The crisis of the 1930s accelerated a trend in the world system to move toward greater state intervention and planning. The next major crisis, in the 1970s, initiated a trend toward privatization and deregulation as part of a strategy to restore profitability. Today’s financial crisis is going to lead to another alternative in which some variant of government intervention and regulation is going to be employed. So long as the system survives, the shifts in approaches of world capitalism will develop as strategies to maintain capitalist social relations rather than fundamentally alter them. And though both neoliberalism and Keynesianism in their day were touted as means to overcome the business cycle, neither has proven capable of eliminating the inherent contradictions of the system, expressed in capitalism’s boom-bust cycle.

It is a sign of just how much the economic literacy of the left has deteriorated that Keynesianism—born as a reforming ruling-class economic program—today may become the default position when calling for an alternative to neoliberalism. Yet socialists must make a distinction between those measures of state intervention—such as the bank bailouts—that are measures of state monopoly capitalism designed to save the bankers to the detriment of the working-class taxpayer; and those measures of state intervention that will come as a result of popular demands. Socialists are not indifferent to the reforms—or the struggles to achieve them—that will be necessary to reverse the three decades of capitalist assault on the working class.

As working-class resistance revives in various parts of the globe, the struggles it takes on will be about restoring certain forms of state intervention benefitting the working class and the poor that neoliberalism stripped away. This will involve resisting or attempting to reverse (as is already happening in some places) the privatization of schools, pensions, and utilities, and the restoration or improvement of state welfare measures and unemployment insurance. It will involve the struggle to resist cutbacks in social services such as health care, education, and transportation. At a higher level of class struggle, it may also mean struggles to compel the state to nationalize collapsing industries in order to save jobs. The crisis and demise of neoliberalism creates the ideological climate in which it is possible to both question the priorities of capitalism and to demand more. It is only in and through these struggles for reforms that the working class will revive and become capable of achieving more fundamental change.

Epigraph: Martin Wolf, “The rescue of Bear Stearns marks liberalization’s limit,”Financial Times, March 25, 2008.

- Robert Brenner, The Economics of Global Turbulence (London: Verso, 2006), xxvii.

- Naomi Klein, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2007), 17.

- Ryan A. Dodd, “A new WPA?,” Dollars & Sense, March/April 2008.

- “Toward a new New Deal (forum),” Nation, March 20, 2008.

- Geoffrey Pilling, The Crisis of Keynesian Economics (London: Croom Helm, 1987), Chapter 1, www.marxists.org/archive/pilling/works/k...

- The text of The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money can be found at the Marxist Internet Archive, www.marxists.org/reference/subject/econo...

- Paul Mattick, Marx & Keynes: The Limits of the Mixed Economy (Boston: Porter Sargent, 1969), 19.

- John Maynard Keynes, The Economic Consequences of the Peace (1919), text taken from McMaster University Social Sciences Web site, socserv.mcmaster.ca/econ/ugcm/3ll3/keynes/peace.htm.

- Keynes, “From Keynes to Roosevelt: Our recovery plan assayed,” New York Times, December 31, 1933.

- Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (1935), Chapter 10.

- Mattick, Marx & Keynes, 117.

- Ibid., 15.

- Keynes, General Theory, Chapter 24.

- Ibid., Chapter 8.

- Karl Marx, Capital, vol. 3, chapter 15, www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1894...

- Quoted in Lenin, The Development of Capitalism in Russia (1899), www.marx.org/archive/lenin/works/1899/dc...

- Marx, Capital, vol. 2 (New York: Penguin Books, 1992), 486–87.

- Engels, Anti-Dühring, Chapter 25, www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1877...

- C. Sackrey, G. Schneider, and J. Knoedler, Introduction to Political Economy (New York: Dollars & Sense/Economic Affairs Bureau, Inc., 2006), 113.

- Keynes, General Theory, Chapter 19.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Keynes, General Theory, quoted in Mattick, Marx & Keynes, 13.

- Quoted in Gabriel Kolko, The Politics of War (New York: Pantheon, 1990), 251.

- Joel Geier, “International Monetary Fund: Debt cop,” ISR 11, Spring 2000.

- Quoted in Mattick, Marx & Keynes, 119.

- U.S. 2008 Statistical Abstract, Industrial Production Index, U.S. Census Bureau, www.census.gov.

- National income figures $82 billion in 1929, $40 billion in 1932, $71 in 1937, and $64 in 1938 in Harry J Carman and Harold C. Syrett, History of the American People, vol. 2. (New York:Alfred P. Knopf, 1952).

- Quoted in CLR James, “Reconversion-1,” New International, March 1945; www.marxists.org/archive/james-clr/works...

- Mattick, Marx & Keynes, 119.

- Ibid., 120.

- Unemployment hovered in the boom period between approximately 3.5 and 5 percent. See Philip Armstrong, Andrew Glyn, John Harrison, Capitalism Since World War II: The Making and Breakup of the Great Boom (London: Fontana, 1983), 240; Marc Linder, The Anti-Samuelson, vol 1 (New York: Urizen Books, 1977), 255.

- Quotes from this paragraph are from Linder, Anti-Samuelson, vol. 1, 256–57.

- For one version of the theory of the permanent arms economy, see Mike Kidron, “A permanent arms economy,” International Socialism, Spring 1967.

- Mattick, Marx & Keynes, 123.

- “Federal budget spending and the national debt,”December 3, 2008, www.federalbudget.com.

- Lee Sustar, “Who caused the great crash of 2008?,” December 5, 2008, Socialist Worker.

- Sackrey, Schneider, and Knoedler, Introduction to Political Economy, 106.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Google+

Google+ Tumblr

Tumblr Digg

Digg Reddit

Reddit StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon