From Nasserism to Collaboration

AS 2009 came to a close, the world was treated to two shameful displays of Egypt’s commitment to enforcing the U.S./Israeli siege of Gaza. First, news reports confirmed that Egypt was beginning construction of a six-mile underground wall made of steel plates. The metal wall is designed to cut off the tunnels that have sustained Gaza’s economy since Israel’s intensification of its blockade of Gaza in 2006, after the people of Gaza freely elected Hamas leaders to govern them. The wall, which is being built with help from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, is supposedly impossible to cut or melt and will plunge more than eighty feet deep in places. Egyptian authorities plan to pump seawater through pipes in the wall in order to make tunneling under the wall a death trap. Of particular concern to Gaza residents living near the wall is that the salt water will destroy the underground freshwater resources that the area depends on for drinking and agriculture purposes.1

Second, the Egyptian government did all it could to frustrate, divide, and thwart the efforts of Gaza solidarity activists attempting to enter Gaza through the Rafah border crossing. The Gaza Freedom March was undertaken to highlight the first anniversary of Israel’s military assault on Gaza that left some 1,400 Palestinians dead, thousands wounded, and tens of thousands homeless. Not only did Egyptian authorities prevent the marchers from traveling from Cairo to Rafah, but security forces also harassed and brutalized the international activists who held public protests to decry Egypt’s decision to block their passage. Egypt’s treatment of the Viva Palestina humanitarian aid convoy was likewise shameful. After more than five hundred convoy participants were told they could cross the border if they made their way to the El Arish port, they were met with beatings that left fifty injured, some severely. The convoy was ultimately allowed into Gaza, but only for a brief time.2

These events beg an obvious question: How did Egypt, once considered a leader of progressive Arab nationalism and a defender of Palestinian national rights, become an open collaborator with the United States and Israel in imposing a siege that defies international law as well as justice to a fellow Arab nation? This collaboration has today made Egypt into an object of scorn, in particular because it seems that the United States has managed to buy its services so cheaply. According to the Middle East Report Online:

Certainly, Israel and the U.S. have been pressuring Egypt for years to “crack down” on smuggling, and, in 2008, Congress withheld $100 million in aid over this issue. And certainly Egypt’s cooperation in maintaining the siege is part of what makes it a valuable U.S. strategic partner. Perhaps not coincidentally, criticism from Washington of Egypt’s human rights record and its illiberal political system has been remarkably muted since the 2007 closure of Rafah. And Egypt has recently won two important concessions from the United States: Part of the aid it receives will now be put into an endowment (which makes it harder for Congress to make the aid conditional on particular reforms); and on December 30, it was announced that Egypt will acquire at least 20 new F-16 fighter jets from U.S. manufacturers.3

But Egypt’s complicity with the siege is not simply a response to externally applied pressure; it’s also the consequence of the regime’s own domestic considerations:

Yet one should not discount Egypt’s internal reasons for backing the blockade. The Egyptian government mistrusts Hamas, an armed militant Islamist group that it considers both an Iranian proxy and an ally of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, its largest and best-organized opposition….

The construction of the subterranean wall is the culmination of a decades-long process of Egyptian disengagement from the Palestinian cause and growing security cooperation with Israel—a process that was given one last dramatic push by Hamas’ election.4

The aim of the rest of this article is to examine the “decades-long process” by which Egypt’s open defiance of Western imperialism in the Middle East has been transformed into a “strategic partnership,” and the implications of this for the struggle for Palestinian liberation.

Nasserism

Owing to its strategic location in the heart of the Middle East and the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, the British Empire considered a compliant Egypt central to the control and maintenance of its far-flung possessions, especially India. The British occupied the Suez area in 1882 to quell a rebellion, and in the words of former New York Times Middle East correspondent Kennett Love, “Egyptian nationalists spent the next 72 years trying to get the British to act on their expressed desire to withdraw.”5

The end of the Second World War thrust the United States into the front ranks of the world’s imperial powers, and the U.S. set about displacing British and French influence in the Middle East—always with an eye to keeping the Soviet Union from establishing influence in the region. Writes historian Lloyd Gardner:

The former colonial era was almost over. In its place the United States had started assembling a new structure that would substitute military connections for the old sinews of empire. The Soviet Union plays a key role, obviously, by offering a “threat,” so that the organization of the “Free World” could be rationalized as “empire by invitation.”6

The growing importance of Middle Eastern oil to the world economy (and the Suez Canal for the transport of this oil to the West) focused Washington’s attention on cementing “friendly relations” with the Arab regimes of the region. However, U.S. support for the fledgling Israeli state, established in 1948, complicated matters. U.S. support for Israel’s colonial takeover of Palestine was difficult to reconcile with this era of decolonization.

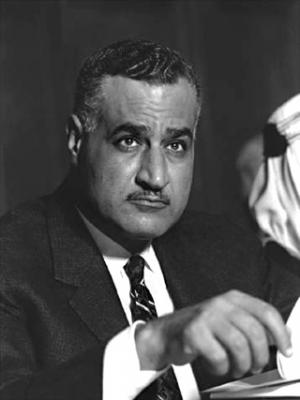

In 1952, a military coup installed a group of junior army officers in power—known as the Free Officers and among them Gamal Abdel Nasser—and drove into exile the pro-British monarch King Farouk. Nasser’s ascendance rode the wave of popular nationalism surging across the region in order to project a vision of pan-Arab unity and resistance to Western powers. This project inspired millions and made Egypt the leader of the section of the Arab world looking for independence from either the United States or the Soviet Union.

As Nasser sought to consolidate his power in post-Farouk Egypt, he looked for leverage in dealing with what was considered the main affront to Egyptian sovereignty: the British military presence. Paradoxically, this meant that Nasser turned to the United States for support, hoping that the rising American influence could be used as a lever to drive the British out. The Americans dispatched Kermit Roosevelt to Egypt, “hoping he would act as Nasser’s tutor, somewhat like the Europeans used to send to Oriental potentates…. Roosevelt’s new mission was to shape the Egyptian into a positive influence on postcolonial leaders in African and Asia. At first Nasser seemed a good pupil, indeed an eager one.”7

But the era of warm relations between the U.S. and Egypt evaporated quickly, as Nasser grew frustrated with the slow pace of arms transfers and the trickle of economic aid that fell far short of what he had anticipated from the United States. The Americans, in turn, drew back from open support for Egypt in order to lessen the strain on its relations with Israel.

Two other developments finally set Nasser on a collision course with the West. First, the 1955 Bandung conference of twenty-nine independent African and Asian countries dramatically increased Nasser’s prestige as the head of what appeared to be a viable bloc of non-aligned nations. Second, just a few months later, Nasser formally announced an arms deal with the Soviet bloc, giving Egypt a source of military hardware that would, it was hoped, allow Egypt to assume its rightful place as leader of the Arab world. The $200 million deal with Czechoslovakia would include 200 MiG-15 jet fighters, 275 T-34 tanks, and a host of other materiel.

Egypt’s patience with the United States was also tested by its struggling economy. In particular, cotton exports, the centerpiece of Egyptian agricultural exports, “had fallen by 26 percent in little over a year, the result, in part, of American agricultural subsidies that permitted U.S. farmers to dump cotton on the world market. China and Russia offered an alternative outlet for the cotton, and a barter deal for arms that would not require cash payments in scarce dollars or pounds.”8

This souring of relations with the West culminated in Nasser’s nationalization of the Suez Canal, putting the canal—and its ability to generate annual revenues on the order of $100 million—under state control. The aggressive move sent a shiver down the collective spine of Western governments. Eager to make Nasser pay for his affront to their interests, Britain, France, and Israel entered into a military pact to invade Egypt. The United States, however, considered this option even worse than living with Nasser’s success, fearing that it could begin a new era of direct occupation by its rivals of a region that the U.S. wished to dominate. American pressure forced Britain and France to withdraw before fully accomplishing their goals, and a few months later, Israel withdrew from the positions it had won in the Sinai Peninsula.

Nasser had emerged the victor.

State capitalism in Egypt

As Nasser’s attempts to win support from the U.S. and the Soviet Union demonstrated, the Egyptian regime elevated pragmatism and realpolitik over a commitment to any particular economic or political program. The question guiding Nasser’s decision was whether any particular political or economic measure served Egypt’s bid to become the undisputed leader of the Arab world. The nationalization of the Suez Canal, combined with Egypt’s ambitious High Dam construction project, had the effect of further propelling Egypt down the road to nationalization of the economy. This was not an uncommon path for many industrializing countries seeking to marshal sufficient concentrations of capital to undertake industrialization and development projects that would enable them to catch up with the already industrialized West.

Although Egypt’s oil production has historically paled in comparison to the Arab Gulf states, Egypt’s political leadership enabled it to benefit from the growing wealth of the oil-rich Arab nations. This also helped to buttress the notion that Egypt was at the head of an Arab nation that was fast becoming a modern force in political and economic terms. “By the mid-1960s, the five largest Arab oil-producing countries—Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Libya, and Algeria—between them had government revenues of some $2 billion a year. The revenues were being used…to build the infrastructure of modern societies, to extend social services, but also to create more elaborate structures of administration and the defense and security structures on which they were based.”9

But it should be stressed that this state capitalist policy was undertaken as a means to direct Egyptian economic development. The alliance with the Soviet Union and Nasser’s revolutionary nationalist rhetoric meant that Egypt’s state intervention in the economy was routinely described as “socialist,” despite the fact that

the transformation of economic structures proceeded on the basis of a state capitalism which in no way altered the capitalist relations of production… However great the aspirations and initial steps towards equality, any further progress was rendered highly problematic by the essential incapacity of this social class [i.e., the bureaucrats in control of the state] to formulate a coherent project. Its very nationalism, which had been intended as a revolutionary force, later served to mystify the crucial socio-economic differentiation of the traditional classes and of the privileged layer emerging from the new state-capitalist class.10

Nasser’s nationalism ultimately secured the rule of an Egyptian elite that used nationalist rhetoric to blunt the demands of the growing Egyptian working class.

Egypt, the Palestinians, and the 1967 war

By the early 1960s, fissures in the Nasserist project to unite the Arab world behind Egyptian leadership began to appear. First and foremost, the Arab world itself was split “between states ruled by groups committed to rapid change or revolution on broadly Nasserist lines and those ruled by dynasties or groups more cautious about political and social change and more hostile to the spread of Nasserist influence.”11 In addition, after nearly twenty years without an independent voice in the management of their own affairs, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) was founded in 1964, and it began to undertake actions within Israel to assert its demands for Palestinian national rights. As a consequence, the Egyptian government, which had acted as the chief spokesperson for Palestinian national demands since the 1948 war, was now one of several currents contending for influence within the Palestinian national movement.

For its part, Israel in the mid-1960s felt itself in a stronger position vis-à-vis its neighbors and welcomed the opportunity to establish this fact by military means.

The population of Israel had continued to grow, mainly by immigration; by 1967 it stood at some 2.3 millions, of whom the Arabs formed roughly 13 per cent. Its economic strength had increased, with the help of aid from the United States, contributions from Jews in the outside world, and reparations from West Germany. It has also been building up the strength and expertise of its armed forces, and of the air force in particular. Israel knew itself to be militarily and politically stronger than its Arab neighbors; in the face of threats from those neighbors, the best course was to show its strength. This might lead to a more stable agreement than it had been able to achieve; but behind this there lay the hope of conquering the rest of Palestine and ending the unfinished war of 1948.12

On June 5, 1967, Israel launched what has come to be called the Six Day War, in which Israel dealt a crushing military blow to Egypt, Syria, and Jordan and occupied, with lightning speed, the West Bank, Gaza, the Sinai Peninsula, and Golan Heights.13 The war achieved Israel’s desired effect of reshaping the balance of power in the region.

It was clear that Israel was militarily stronger than any combination of Arab states, and this changed the relationship of each of them with the outside world. What was, rightly or wrongly, regarded as a threat to the existence of Israel aroused sympathy in Europe and America, where memories of the Jewish fate during the Second World War were still strong; and the swift Israeli victory also made Israel more desirable as an ally in American eyes. For the Arab states, and in particular for Egypt, what had happened was in every sense a defeat which showed the limits of their military and political capacity.14

Contributing to the sense of defeat, Egypt supported the “republican” side of a bloody civil war in Yemen between 1963 and 1969, with some 70,000 troops stationed there at the high point of Egypt’s involvement; at the time, U.S. diplomats considered it Egypt’s Vietnam. After the 1967 war, Nasser was forced to contend with an Israeli military presence in the Sinai, which necessitated devoting even more economic resources to rebuilding the Egyptian army and exacerbated economic stagnation that had already begun to surface in the early 1960s. Nasser concluded that Egypt had no choice but to recognize the existence of Israel, and in short order accepted both the Rogers Plan and United Nations Resolution 242, which established the principle of exchanging territory acquired through force by Israel in exchange for “peace.” Though Nasser largely retained his prestige in the rest of the Arab world, his influence within Egypt was waning.

For the United States, the Six Day War decisively proved Israel’s military effectiveness in challenging Arab nationalism and policing the Arab world, and in the interests of enhancing Israel’s dedication to the role of stalwart defender of U.S. interests, U.S. military and economic aid began to curve sharply upward.

“Infitah”

By the early 1970s, state capitalist measures were no longer able to propel the Egyptian economy forward, as it suffered from heavy debt, high inflation, and high oil prices. Nasser’s death in 1970 and the ascension to power of Anwar Sadat, another of the Free Officers, hastened a trend that was already underway within the Egyptian economy—“infitah,” or the open-door policy. Infitah was a sweeping program to impose a neoliberal agenda on the economy, including the loosening of currency controls, the creation of tax-free enterprise investment zones, and the return of various public sector industries to private control (or at the minimum subjecting them to market pressures).

The open-door policy sought both political and economic changes. “On the political level, rapprochement with the United States was supposed to permit a rapid solution of the Arab-Israel conflict, by the same token extracting Egypt from its state of war. On the economic level, Egypt was to abandon the path of Nasserite ‘socialism’ and take that of an openly capitalist development. In a straightforward calculation of cause and effect, this choice was supposed to attract foreign capital and inject new blood into the Egyptian economy.”15

Egypt had already begun the process of aligning itself with the West in general and the United States in particular even before the official proclamation of the open-door policy in 1974. Not only had Nasser continued to seek U.S. sponsorship, but in 1972 Egypt expelled some twenty thousand Soviet military advisers as the prospect of war with Israel again loomed on the horizon. After the eventual war in October 1973, Sadat considered the outcome a positive one, despite the fact that Israel’s military superiority was now sealed and that American dominance in the Middle East continued to advance.

For Sadat, the war of 1973 had not been fought to achieve military victory, but in order to give a shock to the superpowers, so that they would take the lead in negotiating some settlement of the problems between Israel and the Arabs which would prevent a further crisis and a dangerous confrontation. This indeed is what happened, but in a way which increased the power and participation of one of the superpowers, the USA. America had intervened decisively in the war, first to supply arms to Israel and prevent its being defeated, and then to bring about a balance of forces conducive to a settlement.16

American diplomacy in the aftermath of the 1973 war generally succeeded in achieving its three main goals:

The first was to bring about a general eclipse of Soviet influence in the region…. The second objective was to obtain a political settlement capable of creating a transformation of the very nature of the Arab-Israeli conflict, a settlement that would remove the conflict from its ideological context and transform it into a simple conflict over territory. Such an approach was inherently detrimental to the Palestinians and Arab nationalists, who viewed the struggle as one against settler colonialism and imperialist penetration. The third objective was to provide Egypt with such a vested interest in stability (through economic aid and territorial adjustments) that it would insure its effective removal from the Arab front against Israel.17

Egypt, on the other hand, was not nearly as successful at achieving its objectives with the open-door policy. Egypt’s neoliberal “reforms” did little to convince foreign capital to take the plunge and undertake investment in Egypt. Egypt’s crumbling infrastructure, its fragile transportation and telecommunications networks, and the lingering fear of state expropriation meant that both Western and Arab investors preferred the security of European and American banks. The initial impact of the infitah’s relaxing of import controls was the flooding of Egypt with luxury goods for the rich.

Without the influx of foreign capital, the open door worsened rather than strengthened the economy. Egypt’s poor and working class fared particularly badly. “While the lowest 20 percent of the population held 6.6 per cent of national income in 1960 and had improved their share to 7.0 per cent in 1965, they dropped to 5.1 per cent by the late 1970s. By comparison, the income of the highest 5 percent dipped slightly to 17.4 per cent from 17.5 per cent between 1960 and 1965 but increased markedly to 22 per cent after several years of Sadat’s policies.”18 And in the twenty years between 1961 and 1981, Egypt was transformed from a food exporter to one of the world’s most food-dependent nations, relying on imports for about half of its total food consumption.19

From Camp David to Gulf Wars I and II

In November 1977, Sadat shocked the Arab world by traveling to Jerusalem to negotiate peace with Israel, and a year later the agreement was formalized under American stewardship at Camp David. Israel agreed to return the Sinai Peninsula to Egypt in exchange for full diplomatic and economic relations. The agreement was also supposed to lead to some kind of unspecified “autonomy” for the West Bank and Gaza, but this was left to later discussions. Needless to say, Israel saw no contradiction between this “autonomy” and the continuing construction of Israeli settlements in the Occupied Territories.

In short order, Egypt was expelled from the Arab League, whose headquarters moved from Cairo to Tunisia. (The regimes that expelled Egypt ultimately sought the same accommodation, but their displeasure at Sadat’s unilateral pursuit of peace with Israel remained.) Egypt’s political integration into the Western alliance was complete—and not a moment too soon, as far as Sadat was concerned. Egypt’s economy was reeling, and it was hoped that peace with Israel would allow Egypt to overcome its isolation as well as open up the spigot of American aid. Sadat’s assassination by Islamist forces in 1981 was an expression of the deep bitterness at the path that Egypt was following, but the pattern established in that period remains largely intact right through to the present.20 For example, during Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon:

[President Hosni] Mubarak, like Sadat before him, has looked to the U.S. for his diplomatic cues. By the second week of the invasion, the Egyptian government had quietly adopted [Secretary of State Alexander Haig’s] line as its own, stressing the opportunity for “moderate” Arab states to settle the Palestine problem by expanding the “Camp David process” without the bothersome presence of a militant PLO.21

The Egyptian ruling class has indeed enjoyed handsome rewards for its slavish devotion to U.S. interests. During the 1991 Gulf War, “[w]hen America was hunting for a military alliance to force Iraq out of Kuwait, Egypt’s president [Mubarak] joined without hesitation. His reward…was that America, the Gulf states, and Europe forgave Egypt around $20 billion worth of debt, and rescheduled nearly as much again.”22

Again, during George W. Bush’s 2003 war on Iraq, Egypt was a willing collaborator. In 2006, as the war was at one of its fiercest points, a U.S. State Department official testified as to the continuing importance of U.S. aid to Egypt, despite the concern that Mubarak’s ruthless secret police and torture of his political opponents undermined U.S. claims to be the defenders of democracy in the Middle East. “[American] strategic partnership with Egypt is in many ways a cornerstone of our foreign policy in the Middle East,” said David Welch, assistant secretary of state for Near Eastern affairs. Between 2001 and 2005, Egypt allowed American military aircraft to use its airspace 36,553 times and gave priority to U.S. Navy vessels passing through the Suez Canal.23

The magnitude of U.S. aid to Egypt since the 1970s is staggering. “The U.S. has provided Egypt with $1.3 billion a year in military aid since 1979, and an average of $815 million a year in economic assistance. All told, Egypt has received over $50 billion in U.S. largesse since 1975.”24 Corruption has created a very thin layer of obscenely wealthy Egyptians at the top, starting with Mubarak’s own family that has amassed a fortune counted in tens of millions of dollars. Conditions for the rest of Egyptian society are desperate: unemployment that has remained in double digits for years, per capita income of less than $6,000 dollars annually, and periodic food crises.

But the United States continues to back the Mubarak regime, and Egypt’s value as a strategic asset is well understood in the U.S. foreign policy establishment, even if shallow mainstream media coverage and shortsighted Republican politicians sometimes suggest otherwise. According to the influential Council on Foreign Relations:

Egypt has been cast as an obstructionist force in Israeli-Palestinian negotiations and the U.S.-led war against terrorism. In fact, Egypt has worked quietly and consistently for an Israeli-Palestinian agreement and for an expansion of the Arab world’s acceptance of Israel. Frustration, however, is understandable in the United States—the relationship began with the expectation that peace in the region would have been achieved years ago.25

In truth, U.S. domination of the Middle East begins with Israel and Egypt, but extends far beyond that. Since the 1978 Camp David agreement, the U.S. has effectively leveraged its relationship with Egypt to corral other Arab regimes as allies in the region. Surveying the sweep of U.S. alliances during Bush’s 2003 invasion of Iraq, Tariq Ali wrote:

[A]midst the overwhelming opposition of Arab public opinion, no client regime failed to do its duty to the paymaster-general. In Egypt Mubarak gave free passage to the U.S. navy through the Suez Canal and airspace to the U.S. air force, while his police were clubbing and arresting hundreds of protesters. The Saudi monarchy invited cruise missiles to arc over their territory, and U.S. command centers to operate as normal from their soil. The Gulf states have long become virtual military annexes of Washington. Jordan, which managed to stay more or less neutral in the first Gulf War, this time eagerly supplied bases for U.S. special forces to maraud across the border. The Iranian mullahs, as oppressive at home as they are stupid abroad, collaborated with CIA operations Afghan-style. The Arab League surpassed itself as a collective expression of ignominy, announcing its opposition to the war even as a majority of members were participating in it. This is an organization capable of calling the Kaaba [the most sacred site in Mecca, Islam’s most sacred city] black while spraying it red, white, and blue.26

Egypt and the Palestinians

Egypt’s role in maintaining the siege of Gaza is an extension of its subservience to the overall agenda of the United States. But despite broad support of the Egyptian populace to the national rights of the Palestinian people, the Egyptian regime has always exhibited ambivalence toward the Palestinian cause. In the words of an Egyptian socialist:

The regime uses the Palestine card in a contradictory way. It episodically creates anti-Palestinian and anti-Lebanese feelings to create nationalist hysteria. It also focuses scorn on Hamas and Hezbollah as a way of countering the growing influence of the Muslim Brotherhood, which supports both groups….

For example, as Sadat attempted to consolidate his power, he reacted by unleashing a vicious anti-Arab campaign reasserting that Egypt’s primary identity is “Pharaonic.” A whole period of rejecting Arabism and scapegoating the Palestinians for Egypt’s wars and poverty was led by the state-run media and permeated public culture. This fit the returning bourgeoisie’s desire to reassert itself politically and culturally.27

This argument has gained traction with some segments of the population, but there is also discontent.

The official line that Egypt sacrificed enough for Palestine from 1948 to the 1979 Camp David agreement strikes a chord with some Egyptians. Yet many, across the political spectrum, are deeply uncomfortable with the shift in policy that has turned the Palestinians, from historical “brothers,” into something like enemies. “Egyptian security doctrine has come—incomprehensibly—to consider Gaza and not Israel the main threat to Egypt,” writes Ahmad Yusuf Ahmad. Similarly, the columnist Fahmi Huwaydi remarks that Egypt’s “strategic vision has changed, and Egypt has come to reckon the Palestinians and not the Israelis a danger. And if this sad conclusion is correct, then I cannot avoid describing the steel wall…as a wall of shame.”28

Perspectives for change

Egypt’s ruling class committed itself to the U.S. and Israel decades ago. While it has maintained a rhetorical commitment to the Palestinian cause, this is as thin as it is mandatory. The rhetoric plays no role in guiding Egypt’s foreign policy, but Egypt, like all Arab regimes, must maintain this rhetorical posture if it is to have any hope of ruling over an impoverished population that instinctively identifies with the Palestinian struggle against Israeli colonialism.

Egypt’s ruling class has not misunderstood its own class interests, however. It owes its wealth, its power, and its continued prosperity to an alliance with imperialism. Palestinian liberation, on the other hand, would upset the entire regional balance of power. For Egypt’s ruling class, repression of its own population goes hand in hand with its support of the siege of Gaza.

In a document written for the Israeli socialist organization Matzpen, Moshe Machover and Jabra Nicola (under the pen name “A. Said”) put the network of relationships that underwrite the continuing dispossession of the Palestinian people this way:

The Palestinian people are waging a battle where they confront Zionism, which is supported by imperialism; from the rear they are menaced by the Arab regimes and by Arab reaction, which is also supported by imperialism. As long as imperialism has a real stake in the Middle East, it is unlikely to withdraw its support for Zionism, its natural ally, and to permit its overthrow; it will defend it to the last drop of Arab oil. On the other hand imperialist interests and domination in the region cannot be shattered without overthrowing those junior partners of imperialist exploitation, the ruling classes in the Arab world. The conclusion that must be drawn is not that the Palestinian people should wait quietly until imperialist domination is overthrown throughout the region, but that it must rally to itself a wider struggle for the political and social liberation of the Middle East as a whole.29

The stirrings of such an uprising are difficult to discern at this point in time. There have been substantial signs of growing class struggle in Egypt,30 and there is a looming uncertainty that hangs over the country as an aged and ailing Mubarak attempts to hand power over to his son. Nevertheless, the weakness of the revolutionary left, in Egypt and around the world, means that a revolutionary challenge to imperialism in the Middle East will take years to develop. Short of such an uprising, however, there are important rays of light. Efforts such as the Gaza Freedom March, Viva Palestina, and especially the growing global boycott, divestment, and sanctions movement against Israel are essential to sustaining the Palestinian struggle for national rights.31 But ultimately, unity between the Palestinian struggle and the workers of Egypt and the rest of the Arab world are an essential ingredient if there is to be any chance of real liberation.

Thanks to Adaner, Ahmed, Jonah, and Mostafa.

- Rory McCarthy, “Egypt building underground metal wall to curb smuggling into Gaza,” Guardian, December 10, 2009, and Lina Attalah, “Will Egypt’s underground wall end the Gaza tunnel trade?” Electronic Intifada, January 8, 2010, www.electronicintifada.net/v2/article109.... For background about the tunnel’s importance to Gaza’s economy, see Eric Ruder, “Gaza’s tunnel economy,” Socialist Worker, August 19, 2009.

- Eric Ruder, “A victory for Viva Palestina,” Socialist Worker, January 8, 2010.

- Ursula Lindsey, “Egypt’s wall,” Middle East Report Online, February 1, 2010, http://www.merip.org/mero/mero020110.html.

- Ibid.

- Quoted in Lloyd C. Gardner, Three Kings: The Rise of an American Empire in the Middle East After World War II (New York: The New Press, 2009), 136.

- Ibid., 151–52.

- Ibid., 148.

- Ibid., 157.

- Albert Hourani, A History of the Arab Peoples (New York: Warner Books, 1991), 410.

- Marie-Christine Aulas, “State and ideology in republican Egypt,” in Fred Halliday and Hamza Alavi eds., State and Ideology in the Middle East and Pakistan (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1988), 137.

- Hourani, A History of the Arab Peoples, 409.

- Ibid., 412–13.

- Despite the widely accepted narrative that Israel had to defend itself from the Arab Goliath that surrounded it, Israel was the aggressor in 1967. See Norman Finkelstein, Image and Reality of the Israel-Palestine Conflict (London: Verso, 1995), Chapter 5 on the 1967 war and Chapter 6 on the 1973 war. For a dissection of the general argument that Israel was forced to wage a succession of “defensive wars” between 1948 and 1973, see Noam Chomsky, The Fateful Triangle: The United States, Israel and the Palestinians (Boston: South End Press, 1983), 98–103.

- Hourani, A History of the Arab Peoples, 413–14.

- Marie-Christine Aulas, “Sadat’s Egypt,” New Left Review I/98: July–August 1976, 84.

- Hourani, A History of the Arab Peoples, 419.

- Naseer Aruri, Dishonest Broker: The U.S. Role in Israel and Palestine (Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 2003), 21–22.

- Marvin Weinbaum, “Egypt’s ‘Infitah’ and the politics of U.S. economic assistance,” Middle Eastern Studies, vol. 21 no. 2 (April 1985): 217.

- Ibid., 206.

- Hourani, A History of the Arab Peoples, 420–21.

- Judith Tucker and Joe Stork, “In the footsteps of Sadat,” MERIP Reports, no. 107 (July–August, 1982): 3.

- “The IMF’s model pupil,” The Economist (U.S. edition), March 20, 1999.

- Rick Kelly, “Bush administration defends US military aid to Egypt,” World Socialist Web Site, May 22, 2006, www.wsws.org/articles/2006/may2006/egyp-....

- Charles Levinson, “$50 billion later, taking stock of U.S. aid to Egypt,” Christian Science Monitor, April 12, 2004.

- Council on Foreign Relations paper, “Strengthening the U.S.-Egyptian relationship,” May 2002, www.cfr.org/publication/8666.

- Tariq Ali, Bush in Babylon: The Recolonisation of Iraq (London: Verso, 2003), 159.

- Personal correspondence between the author and an Egyptian socialist, January 24, 2010.

- Lindsey, “Egypt’s wall.”

- Moshe Machover and A. Said (Jabra Nicola), “Arab revolution and national problems in the Arab East,” The International, Summer 1973.

- The ISR reported on Egyptian workers’ strikes in the face of skyrocketing food prices in Hossam El-Hamalawy, “Revolt in Mahalla,” International Socialist Review 59, May–June 2008.

- For more information about these efforts, see www.gazafreedommarch.org, www.vivapalestina.org, and www.bdsmovement.net.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Google+

Google+ Tumblr

Tumblr Digg

Digg Reddit

Reddit StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon