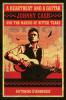

Strong medicine man

A Heartbeat and a Guitar:

It’s hard to disagree with the sentiments expressed in “Shuttin’ Detroit Down,” a song released in April by country music sensation John Rich—one-half of the multi-platinum duo Big & Rich. In the simple bare-bones composition, the singer blends sorrow and outrage into a powerful mix directed against bankers and executives running off with our tax money as ordinary folks lose homes and jobs. There’s one problem: Rich chose to debut the song on the nightly show of his “good friend,” Fox News’s Glenn Beck, and its release was scheduled to coincide with Rick Santelli’s venomous anti-tax “tea parties.”

What’s the lesson here? Merely that context counts. Not only did Rich’s song lend credibility to the wolf-in-sheep’s-clothing “populism” of Fox News, he bolstered country’s long-standing image as the chosen music of backward, everything-phobic “rednecks.” Believe it or not, that image hasn’t always been accurate.

It’s here that Antonino D’Ambrosio’s new book comes in handy. A Heartbeat and a Guitar: Johnny Cash and the Making of Bitter Tears is a passionate and painstaking portrait of one of country’s greatest legends—and the album that launched him into the center of mid-1960’s controversy.

By the early sixties, Cash had become nothing short of a superstar in popular music. In a little less than a decade, the son of poor Tennessee sharecroppers had gone from an artist with gospel ambitions to one of a handful of artists representing the intersection between country, folk, and the burgeoning genre of rock and roll. Record companies saw him as a golden boy.

And yet Cash, far from feeling liberated by the fame, felt hemmed in. One of his reasons for parting ways with Sam Phillips’ Sun Records in favor of Columbia was that he felt the latter to be a place that provided more creative freedom. Cash had been raised on some of the best traditions of American music—songs that gave voice to a stark reality of work, struggle, and hope. Merle Travis. The Carter Family. Woody Guthrie. These were the artists whose legacies Cash hoped to continue. With America’s post–McCarthy hangover giving way to an era of social and political protest, Cash had the opportunity to make the record he wanted.

In the pop culture version of Cash-ology, Bitter Tears is an often-overlooked album. In a recent interview, D’Ambrosio points out “most of the biographies on him—they have one paragraph on it, or a page maybe. But it’s funny because in all the research I did, Bitter Tears is one of two or three albums that he always said were his favorite and best. That says something.”

Released in October of 1964, Bitter Tears was met with immense hostility from the record industry and country music establishment. Radio stations refused to play songs from it. The irony today is that the album contains what is possibly one of the best-known songs in all of Cash’s repertoire: “The Ballad of Ira Hayes.”

Hayes, a real-life member of the indigenous Pima tribe, is himself immortalized: He was one of the four marines photographed raising the Stars and Stripes after the battle of Iwo Jima during the Second World War. But as the song shows, his story was far from one of triumph. Initially coming home to a hero’s welcome, Hayes was soon reminded that he had fought for a country that hated him. His own demons became too much to bear, and he was found dead at the age of thirty-two, having drunk himself to death on the Gila River Reservation, ten years after Iwo Jima.

The plight of Native peoples like Hayes was a deep concern for Cash (who always claimed Cherokee ancestry), and it’s this theme that runs through every song on Bitter Tears. In his book, D’Ambrosio weaves together the stories of the myriad figures and groups that influenced the album’s content—both directly and indirectly.

The list of people isn’t just the early figures of country music, but radicals and subversives that might shock even the most learned Cash fan—in particular, the Greenwich Village folk scene. The people and art that emanated from this small section of New York City had a profound affect on countless musicians of the decade, including Johnny Cash.

D’Ambrosio spends an ample amount of space divulging details of Cash’s connection with the Greenwich scene—whose counter-cultural stance seems to fly in the face of country’s supposed conservatism. Of particular note is the relationship to a young Bob Dylan. The two were much more than casual acquaintances. As the author chronicles, Cash had such respect and affection for the young folksinger that he was one of the few to stand up for him after his notorious electric performance at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival.

And then there was Peter La Farge. La Farge was a Navy veteran who had spent years as something of a wandering soul before settling in the Village. Son of Native rights advocate and writer Oliver La Farge, Peter and Johnny Cash shared a lot in common. Both were steadfast on putting meaning into their songs—and fought tooth and nail with record companies for their right to do so. Both struggled with addictions to pills. And though both claimed Native heritage, in La Farge’s case it was verifiably untrue.

Nonetheless, the mistreatment of Native peoples stirred both of them to absolute outrage. When the two met in May of 1962—after Cash’s disastrous, Dexedrine-fueled appearance at Carnegie Hall—they connected immediately. “Johnny Cash loved him,” says D’Ambrosio, “and in the short time they spent together he was incredibly inspired by La Farge.” Of the eight songs that would appear on Bitter Tears, La Farge wrote five—including “The Ballad of Ira Hayes.”

In some ways, A Heartbeat and a Guitar is just as much a biography of Peter La Farge as it is a story about Johnny Cash. This is certainly not to the author’s discredit, because despite his important contribution to the history of folk and protest music, La Farge largely remains a footnote today. His death in 1965, not long after the release of Bitter Tears, contributes to his present-day obscurity.

Just as important as the stories of the people in A Heartbeat and a Guitar are the stories of what was happening around them. D’Ambrosio steers clear of the tired formula of music bios that tend to portray their subjects in a vacuum. As the author traces the development of Cash’s career and music, so does he give the reader a sense of the civil rights movement, the McCarthyite hangover that still plagued much of the U.S., and, crucially, the burgeoning movement for Native rights.

The fifties and sixties saw countless examples of the racist attitude held by the American government toward Native peoples. D’Ambrosio gives ample space to describing the betrayals of treaties, the stealing of reservation land, and the resistance that sprang up against them. Key players in the Native movement, like John Trudell and Dennis Banks, are interviewed, and the groups that would give rise to what would later be called “Red Power” are also profiled.

Cash had long been at odds with record labels over his content. While Columbia put pressure on him to be a pop star, the singer couldn’t help but be moved by what was going on around him. Making an album like Bitter Tears certainly didn’t ingratiate him with the bigwigs. D’Ambrosio makes the case that “it was hard to be a vocal supporter of Civil Rights—this is 1964. To even go a step beyond that and support Native people—there’s a lot of bravery and courage in that.”

Of all the complex characteristics that Cash held, that is the one most strikingly displayed in A Heartbeat and a Guitar—his courage to stand for what he believed in. After radio stations refused to play “The Ballad of Ira Hayes,” Cash reached into his own pocket to pay for a full-page letter in Billboard magazine lashing out at the “gutless” music establishment that refused to let artists relate to the world around them. “Ira Hayes’ is strong medicine,” he said in the letter, “so is Rochester, Harlem, Birmingham and Vietnam.”

The censorship that Bitter Tears encountered prevented it from gaining the acclaim Cash’s previous work garnered. This might account for its present diminished status among his admittedly massive catalogue. To those in the Native rights movement, however, the album was of great importance. Dennis Banks is quoted in the book as saying “Cash’s album is one of the earliest and most significant statements on behalf of Native people and our issues.”

Red power. Civil rights. War. Johnny Cash could have decided against letting these phenomena inform his art. He could have played the role of the compliant country star, bowing to what the establishment expected of him: Shut up and sing. But then, that wouldn’t have made him into the Johnny Cash so widely admired today. Though A Heartbeat and a Guitar may only focus on a brief snippet of the singer’s life, it nonetheless makes the case that his work is intimately intertwined with his deep sense of social conscience. The brewing storm of the sixties gave that conscience—and his will to test the limits of what was acceptable—the room to thrive.

If nothing else, this book can help bring attention to an important album that has yet to receive its due. Bitter Tears is a testament to what happens when the boundaries between art and politics are broken down. As D’Ambrosio says, “this is the truest representation of Johnny Cash. He tried to do something different and say something different. And I think that really, that’s what good art is about.”

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Google+

Google+ Tumblr

Tumblr Digg

Digg Reddit

Reddit StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon