Revolutionary betrayed

Trotsky:

LEON TROTSKY has been hated by many down through the years. He was hated because he was one of the great Marxist theorists of the twentieth century. He was hated because, along with Lenin, he was a leader of the 1917 workers’ revolution in Russia and of the worker-peasant alliance that helped make the revolution possible. He was hated because he was an organizer and leader of the Red Army that defended the new revolutionary government of councils (soviets) of workers and peasants during the horrific civil war and devastating foreign assaults of 1918–1920. He was hated because he was an opponent of the bureaucratic corruption and authoritarianism that betrayed the revolution. He was hated because he defended the heroic ideas and ideals of the Russian socialist movement’s left wing, the Bolsheviks, against the murderous dictatorship of Stalin’s “communism.” He was hated because for all of his life he labored to build a worldwide struggle against all forms of oppression and tyranny, and for working-class insurgencies dedicated to creating a socialist future. In short, for those seeking a better world, he is a person worth knowing something about.

A “definitive” biography?

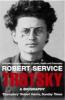

Oxford historian Robert Service has now published what he describes as “the first full-length biography of Trotsky written by someone outside Russia who is not a Trotskyist”—an inflated and inaccurate claim that has, nonetheless, been repeated by numerous reviewers. In fact, the overwhelmingly enthusiastic response by most of the book’s reviewers is instructive, particularly in light of the inflated assertions and shocking inaccuracies that characterize this irredeemably shoddy scholarly performance. Before looking at the biography itself, it is worth considering the effusions of its prestigious admirers.

The Washington Times has hailed this “authoritative biography” of Trotsky as an “illuminating portrait” that “sets the record straight.”Publishers Weekly has praised it as “a pleasure to read,” adding that it “should remain the definitive work for some time.” Writing for theMinneapolis Star Tribune, Michael Bonafield, has depicted Service’sTrotsky as “iconoclastic yet rigorously balanced,” and as an “impressive book” which is “encyclopedic” and “oh, so well written.” And in the pages of Commentary, Peter Savodnik has characterized it as “fascinating, detailed, intelligent, and meticulously researched.” A reviewer in the New Yorker selects it as “the Favorite Nonfiction Book of 2009.”

In Britain, the enthusiasm hit an even higher pitch. The book has been acclaimed by the Evening Standard as one of the “best books of the year” for 2009. The Independent concurred. It was awarded the Duff Cooper Prize for the best in non-fiction writing for 2009. The Sunday Times reviewer Robert Harris has hailed Service’s work as “exemplary.” For the Daily Telegraph, Simon Heffer expressed deep admiration for Service’s “superb work of scholarship.” Historian Simon Sebag Montefiore lauded it in the Sunday Telegraph as “an outstanding, fascinating biography” which is not only “compelling as an adventure story,” but also “revelatory as the scholarly revision of a historical reputation.” And so on.

The scholarly apparatus that Service provides in his book certainly suggests that the author explored a wealth of sources. These include materials from the frequently examined Trotsky archives at Harvard and in Amsterdam, but also extensive materials from the Hoover Institution Archives at Stanford, and from party and state archives in Moscow opened since 1991. Some of the newly uncovered materials include personal letters, party and military correspondence, medical records, memoirs, and unpublished drafts of Trotsky’s writings. Service’s labors in these archives have uncovered various quotations and anecdotes that provide occasional insights into aspects of Trotsky’s private life. (For example, there is the charming image found in the autobiographical notes of Trotsky’s wife Natalia Sedova, of Trotsky decorating a Christmas tree in Vienna, coupled with her observation that both felt distaste for “the orgy of present-giving.” No wonder capitalists hated this man!)

But, in light of Service’s claims, and the extensiveness of the research involved in producing this book, it is surprising just how few of these nuggets there are, and how little they affect what we previously knew about Trotsky’s politics.

Character assassination

Even a casual reader of this volume will get a very definite sense that its author is on a crusade. At the outset Service announces that his goal is “to dig up the buried life” of Trotsky. For Service this involves demonstrating that “Trotsky was no angel”; rather, he was a man driven by a “lust for dictatorship and terror.” As Service is reported as explaining at one promotional appearance, “I wanted to bring down the edifice…. [Trotsky’s] ideals and practices in power were an anachrony [sic] to decent values.”1

This is not to say that the biography is unrelentingly critical of Trotsky. In a display of objectivity, Service notes what he views as Trotsky’s more admirable qualities. He characterizes Trotsky as “an outstanding speaker, organizer and leader” who also had “a sensitivity…for literature.” He praises Trotsky’s physical courage, notes his modesty, and compliments his “neat handwriting.” For Service, this list essentially exhausts the inventory of Trotsky’s assets.

Instead, Service prefers to dwell on Trotsky’s shortcomings—his self-absorption, his vanity, his arrogance, and his insensitivity to the feelings of others. Of course, none of this is new. As Service emphasizes, all of these personal weaknesses were noted at times by Trotsky’s associates, friends, and family; and they have been discussed by other biographers. In fact, some, such as Trotsky’s tendency to adopt a “pedantic and exacting attitude…insufferable in personal relationships,” were conceded by Trotsky himself.2 For Service these traits were overarching character flaws that shaped Trotsky’s entire life and decisively determined his political fate.

This perception of Trotsky’s flaws underlies what one academic reviewer has described as Service’s “curiously mean-spirited commentary on Trotsky’s relationships with his parents, wives, and children.”3 One example, reiterated throughout the book, concerns the fact that Trotsky left behind his wife Alexandra Sokolovskaya and two young daughters when he escaped from Siberian exile in 1902. As Service crudely puts it, “No sooner had he fathered a couple of children than he decided to run off.” He “ditched his first wife,” and he “abandoned her and their tiny girls in Siberia.” Although Service notes that Trotsky later claimed Alexandra had “wholeheartedly blessed” his departure, he dismisses this as “hard to take at face value,” for “Bronstein was preparing to abandon her in the wilds of Siberia.” In fact, however, Trotsky’s later claim was stronger: Sokolovskaya “was the first to broach the idea.” When he raised objections that this would place a “double burden” on her in the difficult conditions of Siberian exile, she responded only, “You must,” and it was her urging that ultimately succeeded in convincing Trotsky.4 Service is entitled to his skepticism, but it is the only first-hand account we have of this episode. Furthermore, it seems entirely plausible in light of the commitment of both to the revolutionary cause, and the apparently close relationship between her and Trotsky’s family in later years.5

A second family episode that exemplifies Trotsky’s self-absorption for Service was the suicide of his daughter Zina in 1933. Service blames Trotsky directly, suggesting he could have found something for her to do around the house rather than shipping her off to Berlin for medical attention: “Zina had gone to death when a little dosing of parental consideration might have made all the difference.” But Zina was mentally ill. Service admits she was suspected of starting a series of fires in Trotsky’s homes in Turkey, and in Germany she was diagnosed as schizophrenic. What, then, is the basis for Service’s assertion that just a little “parental consideration” on Trotsky’s part could have saved her?

By 1917, according to Service, Trotsky’s character flaws had blossomed—he does not tell us how—into a fundamental “lack of humanity.” In Service’s account, this was evident in Trotsky’s advocacy of a “dictatorial and violent” regime in the months preceding the Bolshevik Revolution, in his “lust for dictatorship and terror” in the civil war, in his use of executions against deserters from the Red Army, in his call for a “total subjugation of the workers’ movement to the Soviet state” in 1920, in his “campaigns of bloody repression” against Kronstadt sailors and insurgent peasants in 1921, and in his support for the repression of opposition parties and opposition factions within the Bolshevik Party. All of this provides the basis for the central theme of the book—that there was no fundamental difference between Trotsky and Stalin: Trotsky’s “ideas and practices laid several foundation stones for the erection of the Stalinist political, social, and even cultural edifice”; and Trotsky “was close to Stalin in intentions and practice.” This story, eagerly embraced by so many reviewers, is questionable, to say the least.

Distorting the historical record to score political points

To demonstrate Trotsky’s advocacy of a “dictatorial and violent regime,” Service highlights a particularly disturbing “quotation” (frequently reiterated by appreciative reviewers) from an address by Trotsky to the Kronstadt naval garrison in 1917: “I tell you heads must roll, blood must flow.… The strength of the French Revolution was in the machine that made the enemies of the people shorter by a head. This is a fine device. We must have it in every city.” Service’s source—and the only source for this quotation—is the account of Wladimir Woytinsky.6

But Woytinsky’s memoirs are suspect. He was a former Bolshevik who went over to the Mensheviks in 1917, and as historian André Liebich has noted, in that year Woytinsky quickly “became more anti-Bolshevik than majority Mensheviks.” Liebich further observes that “Scarlet Pimpernel-like anecdotes and a curiously naive tone of self-satisfaction weaken [Woytinsky’s] memoirs’ credibility.” (One of Woytinsky’s other astounding claims was that, following the October Revolution and after Woytinsky had become a Menshevik, Lenin asked him to join the Council of Peoples’ Commissars as “War Minister and Supreme Commander”!)7

Regarding the institution of the “Red Terror” in the following year, Service argues that this was plotted in advance by Lenin and Trotsky because they wanted “to carry out the irreversible suppression of the enemies of the October Revolution.” A recent study by a more careful historian, Alexander Rabinowitch, has concluded that, on the contrary, it was not the product of “a nationwide political crackdown inspired by Lenin,” but “the culmination of a gradual process during which the moderating influence of…key individuals…was replaced by pressure for systematic Red Terror, in part ‘from below’,” in large measure due to assassinations of prominent Bolsheviks (and a nearly successful attempt which left Lenin badly wounded) that were perceived as being part of “a coordinated domestic and international conspiracy to overthrow Soviet power.”8

Aside from questionable details and interpretations, perhaps the greatest deficiency in Service’s account of the early years of the revolution is his failure to provide a sufficient historical context for Trotsky’s actions. One would hardly know from reading Service that 1918–1920 were cruel years in which the Bolsheviks and their working-class supporters found themselves engaged in a harsh struggle for survival against a vicious enemy. Some of this comes through, however, in a recent exchange between Service and the ex-Trotskyist Christopher Hitchens, in which Hitchens reminded Service that “If Trotsky’s Red Army had not won the Russian Civil War, then the word for fascism—we have to face the fact—was probably going to be the Russian word instead of an Italian word.” To this, Service was forced to concede, “It’s a little exaggerated, but it’s pretty fair that the Whites had officers who were vicious, carried out a brutal civil war against the Reds.”9

The devastation of the First World War, the Russian civil war, the foreign economic blockade and military intervention, combined with inevitable mistakes by the revolutionaries, generated additional problems. Not only did these conditions block the realization of the revolution’s goals of a genuine soviet democracy, but discontent within the revolution’s peasant and working-class base posed a tragic challenge to the Bolshevik regime. In 1920–21, just emerging from the civil war, the Bolsheviks were confronted with the rebellion of peasants in the Tambov region and of sailors at the Kronstadt naval base that threatened to reignite the civil war and open the door to renewed foreign intervention. (Interestingly, Service chastises Trotsky because he refused in his autobiography “to allow that the Kerenski regime had reason to take measures against people who were plotting its armed overthrow.” But by that logic, was it less legitimate for the Bolshevik regime to take measures against people who actually had taken up arms against it?) Subsequently, in the context of a situation made even more explosive by the reintroduction of the market under the New Economic Policy, the Bolsheviks moved in 1921 to introduce a temporary ban on opposition parties and factions.

Of course, there is no need to approve of all of these repressive and authoritarian actions, or to endorse all the arguments advanced by Trotsky and others to justify them. One could argue that many of these actions were inexcusable, and their justifications were false—yet a minimal degree of historical objectivity requires at least a consideration of the Bolsheviks’ concerns. It also requires a rejection of the double standard applied by Service. For that matter, it requires recognition of the fact that Trotsky’s own thinking regarding all of this continued to evolve in later years. In the mid- to late-1930s, for example, Trotsky came to admit that the banning of opposition parties was “obviously in conflict with the spirit of Soviet democracy” and that it indisputably “served as the juridical point of departure for the Stalinist totalitarian system.” He concluded that the “exceptional measure” of banning factions, even applied “very cautiously” had subsequently “proved to be perfectly suited to the taste of the bureaucracy.”10

Finally, historical objectivity demands some recognition of the significant contextual differences between the repression instituted by the Bolsheviks in defense of the revolution and the new Soviet state against armed enemies, and the repression implemented by the Stalinist regime against its defenseless critics in the 1930s. For Service, however, all of these measures were essentially identical: “Stalin, Trotsky, and Lenin shared more than they disagreed about.” This political distortion is possible only through the distortion of the historical record.

Over and over again, Service bends his sources to score his points. He says of Trotsky that “what counted for him was world revolution, and no human price was too great to pay in the interests of the cause.” An example he cites of Trotsky’s “complete moral insouciance” was a comment to Max Eastman in the early 1920s that “he and the Bolsheviks were willing ‘to burn several thousand Russians to a cinder in order to create a true revolutionary American movement.’” Service comments archly that “Russia’s workers and peasants would have been interested to know of the mass sacrifice he was contemplating.” But if we turn to Eastman’s own account, we find that the topic under discussion was the role of Russian-American immigrants in the new Communist Party in the United States. Eastman was complaining that “the self-importance and organizational dominance of Russian-Americans in the party councils, made it impossible to get an American revolutionary movement started.” At which point Trotsky suggested with amused exasperation, essentially, that the Bolshevik regime should have the sectarian offenders burned at the stake.11 Service apparently assumes that his readers will not be inclined to check an old memoir to see whether or not he is telling the truth.

Shoddy scholarship

The entire landscape of Service’s biography is littered with basic factual inaccuracies, both small and great. The following examples, many of which have been noted by other reviewers on the left, are indicative:12

- Service states that Trotsky spoke out against individual terror in 1909 when the Socialist Revolutionaries “murdered” police informant Evno Azev. In fact, Azev died in 1918 in Berlin, apparently of kidney disease.13

- The author asserts that, in a significant break with Jewish tradition, Trotsky and Sedov named their first son Sergei, rather than Lev after Trotsky. Actually, Trotsky’s first son was Lev.

- In his discussion of the German Revolution of 1923, Service relates that “street fighting petered out” quickly in Berlin and that in other German cities communists were even less effective until the central leadership ultimately “called off its ill-planned and ill-executed action” on October 31. In reality, the leadership of the German Communist Party called off the planned insurrection on October 21. There was no street fighting in Berlin; only Hamburg failed to receive the cancellation message and rose in revolt.14

- The author states that Gregory Zinoviev was expelled from the Politburo in 1925. That expulsion occurred at the Central Committee plenum of July 1926.15

- Service asserts, “There can hardly be a doubt that Stalin and Bukharin bungled by sending instructions through the Comintern for the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to organize an insurrection against Chiang Kai-shek and the Kuomintang in April 1927.” In fact, there were no such instructions and no such insurrection. In March 1927, a successful workers’ uprising against the local warlord in Shanghai transferred control of the city to Chiang’s National Revolutionary Army. Subsequently, on April 12, Chiang launched his own bloody coup against the workers. Throughout these events, the operative instructions from Moscow were for the CCP to avoid clashes with Chiang and his army.16

- Service confuses the October 15, 1927, demonstration in Leningrad following the session of the Central Executive Committee of the soviets with the November 7 demonstration in honor of the tenth anniversary of the revolution.17

- The author incorrectly identifies the Sixth Comintern Congress in 1928 as the Fifth.

- Noting Trotsky’s appreciation in 1936 of French writer André Gide’s account of his visit to the Soviet Union, Service quips that Trotsky still “would not bestir himself to go and make Gide’s acquaintance: he expected the mountain to come to Mohammed.” But the “prophet” could not have visited Gide at home in 1936. Under a French order of expulsion, Trotsky had been forced to seek asylum in Norway in June 1935.18

- Service explains that Trotsky received a French visa from Daladier’s coalition government formed at the beginning of 1934. The coalition government was formed in early 1933, and Trotsky received a French visa in July of that year.19

- Service repeatedly depicts André Breton as a “surrealist painter.” In fact, Breton was a surrealist poet, critic, and theorist.

- Service confuses Bernard Wolfe, briefly one of Trotsky’s secretaries and bodyguards, with Bertram D. Wolfe, a leader in the late 1930s of Jay Lovestone’s Independent Labor League of America.

- Service states that “by the afternoon” of Wednesday, August 21, 1940, American radio stations “were confirming that [Trotsky] had breathed his last.” Trotsky did not die until approximately 8 p.m. that evening.20

- Service asserts that Trotsky’s widow, Natalia Sedova, died in 1960. Actually, she died on January 23, 1962.21

- Service incorrectly identifies Genrietta Rubinshtein and her daughter Yulia Aksel’rod as the wife and daughter of Trotsky’s older son Lev. They were the wife and daughter of his younger son, Sergei.22

This dismal list is by no means exhaustive. Of course, minor errors have a way of creeping into any manuscript. But sloppiness on this scale, in what is supposed to be a serious historical work (hailed as a “superb work of scholarship” that “sets the record straight”), is astounding. What actually happened in history seems of secondary importance to this biographer, and to his admirers, who are dedicated to revealing what for them is a larger political truth: Trotsky “fought for a cause that was more destructive than he had ever imagined.” One had best steer clear of it.

Something better

Simply cataloging and documenting the historical, factual, and interpretative limitations of this biography would require a review several times longer than this one. To the extent that this book is useful, it is primarily as a model of how not to understand Trotsky. However, for someone looking for the opposite, a reasonable place to begin may be some of Trotsky’s writings—for example, My Life, The History of the Russian Revolution, and The Revolution Betrayed. Additionally, there are informative biographies of varying lengths—by Isaac Deutscher, Victor Serge and Natalia Sedova, Tony Cliff, Pierre Broué (for those fluent in French), and Dave Renton. Even Irving Howe’s short, thoughtful, social-democratic interpretation offers a far more honest rendering than what one finds in Service. Studies by such critical-minded interpreters as Kunal Chattopadhyay, Duncan Hallas, Michael Löwy, and Ernest Mandel also merit attention.

Despite the apparent assumptions of Service and his admirers, we have not bypassed the world that Trotsky so brilliantly analyzed and so bravely struggled to change. Many of the problems Trotsky struggled with continue to plague us, while new problems generated by capitalism continue to emerge. In this context it makes sense to do the opposite of what Service seems to favor, and to continue to engage with Trotsky’s ideas and example.

- Quoted in “Service with a snarl: Academic refuses to answer questions,” The Socialist, November 18, 2009.

- Leon Trotsky, Writings of Leon Trotsky [1937–38] (New York: Pathfinder Press, 1976), 169–70.

- Juliet Johnson, “Trotsky: as bad as Stalin?; Pretty much so, according to a major new biography,” Globe and Mail (Canada), January 23, 2010.

- Leon Trotsky, My Life: An Attempt at an Autobiography (New York: Pathfinder Press, 1970), 132.

- See for example, Service, Trotsky, 84, 108, 166, 194, 431. See also the communications from Sokolovskaya to Leon Sedov in Leon Trotsky, Trotsky’s Diary in Exile 1935 (New York: Atheneum, 1963), 79, 159–60.

- This passage appeared in 1961 Woytinsky’s memoirs, published posthumously in 1961. See W.S. Woytinsky, Stormy Passage: A Personal History Through Two Russian Revolutions to Democracy and Freedom: 1905–1960 (New York: Vanguard Press, 1961), 286. For a slightly different version of this “quotation,” see Bertram D. Wolfe, “Leon Trotsky as historian,” Slavic Review, Vol. 20, No. 3, 1961:498.

- André Liebich, From the Other Shore: Russian Social Democracy after 1921(Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1997), 66, 341, 362; Woytinsky, Stormy Passage, 377.

- Alexander Rabinowitch, The Bolsheviks in Power: The First Year of Soviet Rule in Petrograd (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2007), 398.

- “Trotsky with Hitchens and Service,” Hoover Institution, Stanford University, taped on July 28, 2009, available at media.hoover.org.

- Leon Trotsky, The Revolution Betrayed: What Is the Soviet Union and Where Is It Going? (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, Doran & Co., 1937), 96; Leon Trotsky, Stalinism and Bolshevism (New York: Pathfinder Press, 1970), 22.

- Max Eastman, Love and Revolution: My Journey Through an Epoch (New York: Random House, 1964), 332–33.

- David North has done an especially thorough job identifying factual errors in Service. See David North, “In the Service of historical falsification: A review of Robert Service’s Trotsky: A Biography,” November 11, 2009, www.wsws.org; David North, “Historians in the Service of the ‘Big Lie’: An examination of professor Robert Service’s biography of Trotsky,” December 15, 2009, www.wsws.org. See also Paul Le Blanc, “Trotsky lives!” International Viewpoint, IV Online Magazine: IV 419, December 2009, www.internationalviewpoint.org; Paul Hampton, “Review of Robert Service’s biography of Trotsky,” Workers’ Liberty, November 12, 2009, www.workersliberty.org; Peter Taaffe, “A ‘dis-Service’ to Leon Trotsky,” October 14, 2009, www.socialistworld.net; Joe Auciello, Socialist Action, January 2010, www.socialistaction.org.

- Boris Nikolaejewsky, Aseff the Spy: The Russian and Police Stool (Hattiesburg, Mississippi: Academic International, 1969 reprint of 1934 edition), 286; Richard E. Rubenstein, Comrade Valentine (New York: Harcourt Brace and Co., 1994), 302.

- Pierre Broué, The German Revolution 1917–1923 (Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2005), 805–12; Edward Hallett Carr, The Interregnum: 1923–1924 (New York: The Macmillan Co., 1954), 221–24; Chris Harman, The Lost Revolution: Germany 1918 to 1923 (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2003), 285–88.

- Edward Hallett Carr and R. W. Davies, Foundations of a Planned Economy (New York, Macmillan, 1971), 2:6–9; Robert Vincent Daniels, The Conscience of the Revolution: Communist Opposition in Soviet Russia (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1960), 278–79.

- Alexander Pantsev, The Bolsheviks and the Chinese Revolution, 1919–1927 (Honolulu : University of Hawaii Press, 2000), 127–36. Harold Isaacs, The Tragedy of the Chinese Revolution, second revised edition (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1961), 137–40, 156–85.

- Leon Trotsky, My Life, 532–33; Edward Hallett Carr and Davies, Foundations, 2:37; Isaac Deutscher, The Prophet Unarmed: Trotsky, 1921–1929 (London: Oxford University Press, 1959), 365–66.

- Isaac Deutscher, The Prophet Outcast, Trotsky, 1929–1940 (London: Oxford University Press, 1963), 289-290; Jean van Heijenoort, With Trotsky in Exile: From Prinkipo to Coyoacán (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1978), 79.

- Van Heijenoort, With Trotsky in Exile, 45–48.

- Joseph Hansen, “With Trotsky to the end,” October 1940, Marxist Internet Archive, www.marxists.org. On this point Service cites “J. van Heijenoot, With Trotsky in Exile: From Prinkipo to Coyoacán, 192.” There is no page 192 in that book, and the relevant passage on page 146 says nothing about the time of the radio announcements of Trotsky’s death.

- “Trotsky’s widow dies in Paris at 79,” New York Times, January 24, 1962.

- Hoover Archival Documents Project, www.hoover.org.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Google+

Google+ Tumblr

Tumblr Digg

Digg Reddit

Reddit StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon