The neoliberal restructuring of healthcare in the US

As of the beginning of this year, the most significant elements of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) have been implemented. Universally known as “Obamacare”, the ACA represents the most significant alteration in healthcare funding and delivery since the introduction of Medicaid and Medicare in 1965.

In an object lesson in how to shift the political frame of an issue to the right, conservatives have unleashed a torrent of slander against the bill, raising the specter of a Soviet takeover of the US healthcare system. US Congressman Steve King (R-Iowa) proclaimed about the ACA, “It’s control of the means of production. Owning the means of production is Marxism.”12 We could take this comment less seriously except these folks wield actual political power. Rep. King and other Tea Party Republicans led by Senator Ted Cruz (R-Texas), successfully shut down the federal government in the fall of 2013 for 16 days in an attempt to try and repeal the ACA. They failed in their primary goal of killing the legislation, but succeeded mightily in further shifting and narrowing the debate.

But it takes two to tango. Among Democrats, both legislators and rank-and-file supporters, as well as among most of the broader liberal establishment, most are generally in line with the sentiment expressed by President Obama in an interview with NPR, “This notion, I know, among some on the Left that somehow this bill is not everything that it should be—that we still need a single-payer plan . . .—just ignores the real human reality that this will help millions of people and end up being the most significant piece of domestic legislation at least since Medicare and maybe since Social Security.”3

New York Times columnist Paul Krugman also hedged against criticism from the left. “Now, the act—known to its foes as Obamacare, and to the cognoscenti as ObamaRomneycare—isn’t easy to love, since it’s very much a compromise, dictated by the perceived political need to change existing coverage and challenge entrenched interests as little as possible. But the perfect is the enemy of the good; for all its imperfections, this reform would do an enormous amount of good.”4

This has been the debate, solidified by the 24-hour echo chambers of Fox News, CNN, and MSNBC—that healthcare reform is either a Stalinist conspiracy to implement government-controlled healthcare or that it belongs to the legacy of the New Deal and the War on Poverty. The reality that this debate has thus far successfully obscured is that the ACA is, in fact, the rejection of both.

The conservative arguments can be dismissed out of hand. But the liberal version of the story needs to be taken more seriously. After all, there are elements of the legislation that will make people’s lives better, most notably increased regulation on the universally-despised insurance industry and the expansion of Medicaid. The goal of the following analysis is to examine Obama and Krugman’s claims—will the ACA indeed help millions of people? Should it be considered, however flawed, as a step forward for healthcare in this country? The answer to these questions has obvious implications for how the Left understands the ACA and therefore the strategies we develop in our ongoing fight for full access to “everybody in, nobody out” quality healthcare.

This article will examine some of the motivating principles of the ACA and its impact on restructuring health care delivery (hospitals, clinics, etc.). Helen Redmond’s article in this issue, “The Affordable Care Act: The reality behind the rhetoric,” will focus on the impact of the ACA on healthcare coverage.

The Affordable Care Act as neoliberal healthcare reform

The central contention of this article is that the purpose of the Affordable Care Act is not principally to provide access to healthcare for millions of Americans. The primary purpose of the ACA is to control spiraling healthcare costs while facilitating a qualitative leap in neoliberal healthcare restructuring in the United States, freeing up tens of billions of taxpayer dollars to further engorge the highly profitable healthcare insurance companies, private equity firms, and hundreds of other healthcare corporations. For those institutions and individuals who provide healthcare to people who cannot afford certain forms of healthcare coverage, the ACA, as it is currently configured, offers sweeping austerity in the form of drastically reduced federal funding and reimbursement mechanisms. The result, as with education reform, will be a further stratification of healthcare resources and access, more money at the top, and less in the bank accounts of the working class people due to significantly increased out-of-pocket healthcare costs. Indeed, even prior to mandating all Americans obtain (and most often pay for) some form of healthcare coverage, just in the last 12 years the percentage of family income devoted to healthcare has doubled, from 18 percent in 2002, to 35percent today.5

It is well known that the US spends more money per person on healthcare than any other country on the planet, but has close to the worst healthcare outcomes in the industrialized world. According to the WHO, the US spends $8,322 per person on healthcare and ranks 37th in healthcare outcomes. France, by contrast, is number one in health outcomes while spending less than half at $3,997 per person.67 One important question is what made healthcare costs such an exceptionally American problem. The short answer is that the United States was unique among the industrialized countries, particularly in the post-World War II era, in keeping the growing demand for healthcare largely within the confines of the market system. A. W. Gaffney, in an extremely valuable survey of the history of US healthcare policy since the New Deal, traces the failure of the New Deal left to secure a federally-funded national healthcare program as a defining moment. While western European countries, in the midst of what was for them severe post-war economic turmoil, created expansive government-funded healthcare access to their entire citizenry, the US opted to give tax breaks to employers to provide private healthcare insurance. Healthcare costs rose mightily over the ensuing decades as an epic price war was waged between the increasingly for-profit entities, that then provided healthcare goods and services (hospitals, doctors, pharmaceutical companies, and medical supply companies), and the private insurance companies (later the federal programs of Medicaid and Medicare) that pay for the bulk of those goods and services.8

But what arose as an engine of profits and economic growth has now become an economic liability to the overall economy. This is true in terms of healthcare’s overall cost to other sections of capital that pay for health insurance for their workforce, the cost to those that consume healthcare, especially those who don’t have health insurance or who are not eligible for Medicaid or Medicare, and most of all to the US government that currently pays for between a third and a half of all US healthcare spending. Medicaid and Medicare alone accounted for about $1 trillion of the total $2.8 trillion spent on healthcare in 2012.9

According the White House website: “Healthcare expenditures in the United States are currently about 18 percent of GDP, and this share is projected to rise sharply. If healthcare costs continue to grow at historical rates, the share of GDP devoted to health care in the United States is projected to reach 34 percent by 2040.”10 Using this projection, in about 30 years a full third of all the goods and services produced by the US economy would be devoted to the healthcare. Since the bulk of this economic output is currently provided for by federal tax dollars through Medicaid and Medicare, from the perspective of the financial sector, the healthcare sector’s contribution to the ballooning federal budget deficit is reaching a tipping point. After years of Bush-era tax cuts for the wealthy, massive federal bailouts of the finance sector during the 2008 global financial crisis, and the hundreds of billions spent on wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, and ongoing drone strikes, the business class, reflected in both political parties, is very concerned about the size of the federal deficit.

The fiscally-minded reforms imbedded in the ACA should be seen both in the longer-term trend of neoliberal restructuring and the acute reality of the post-2008 worldwide government bailouts of the financial sector. Canadian Marxist David McNally highlights, in his definitive analysis of the crisis in Global Slump, that, for governments, fiscal recovery from this historic binge in wealth transfer will likely require “a decade of pain” in the form of austerity.11

In the US, healthcare is the obvious target for austerity. In the lead up to the passage of the ACA, Robert Greenberg of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities reminded Congress, “The new Congressional Budget Office report shows that rising healthcare costs are the largest driver of the nation’s long-term budget problems.”12 Elizabeth Fowler, a former health insurance executive at WellPoint and well-known signature architect of the ACA, was clear about the chief concern in creating the ACA. She told the New York Times, “Everybody is focused on the coverage angle, but the changes in the law designed to address cost could be a bigger and longer-lasting change.”13 As chief health policy council to Democratic Senator Max Baucus, chairperson of the Senate Finance Committee and the most significant legislator involved in constructing the legislation, Fowler’s words should be weighted, and so should her class outlook. As Glenn Greenwald wrote in The Guardian, “It’s difficult to find someone who embodies the sleazy, anti-democratic, corporatist revolving door that greases Washington as shamelessly and purely as Liz Fowler.”14 She then went on to work for the Obama administration to oversee the ACA’s implementation. After working for the White House, Ms. Fowler now heads global health policy for Johnson & Johnson, among other things a massive medical supply and pharmaceutical company. Healthcare companies are now paying top dollar for people like Fowler. Their expertise in how to navigate the details of the 2,000-page law, and therefore how to increase profit margins from it, is priced at a premium.

There are a number of forces driving increases in healthcare costs. Increased profit extraction by the pharmaceutical, medical supply, and insurance industry that now totals over $100 billion annually, the 31 percent in administrative costs that insurance companies expend in order to extract their profits, severe and widespread price gouging by major medical centers, and the fact that United States has the highest inequality in the industrialized world and therefore a high prevalence of chronic and poorly treated diseases, are among the top contenders.15 The architects of the ACA chose not to directly confront these realities. Instead, according to Obama administration officials, the argument is that rising costs are due to people getting too much healthcare because their doctors and hospitals are ordering too many tests and procedures because they have a financial incentive to do so. “The sources of inefficiency in the US healthcare system include payment systems that reward medical inputs rather than outcomes,” says WhiteHouse.gov.16 This premise is false and is ideologically loaded. As Charles Idelson points out, this analysis:

stems from some highly-publicized abuses of a few practitioners who prescribe diagnostic procedures or medical treatment to profit from reimbursements. But it also coincides with the portrait of patients as a whole class of ‘takers’ who somehow enjoy spending hours waiting in doctors’ offices or undergoing colonoscopies, a theory that has race, gender, and class overtones, blaming minorities, women, and the poor for demanding “too much” care.17

By focusing on one aspect of cost, healthcare utilization, to the exclusion of the other, healthcare profits and the wastefulness of competition in the private sector, the effects of cost containment strategies within the ACA will be to restrict healthcare access even further at the point of delivery—mainly in hospitals and mainly for poor and elderly people.

It is obviously true that the ACA involves massive government expenditures, both in terms of subsidies to insurance companies, funding programs directly, and for Medicaid expansion. So how can more federal healthcare spending reduce federal healthcare spending? Political economist Jacob Hacker explains in the New Republic that the ACA fits perfectly with current economic conditions, offering government-injected economic stimulus in the short-term, and cost savings in the long-term.18 With this framework, the massive injection of federal money into the health insurance industry will increase the customer base for the private healthcare market, while at the same, cutting the “entitlement” programs, most importantly Medicare, but also some elements of Medicaid, that fund healthcare services for not-so-profitable elderly and the poor.

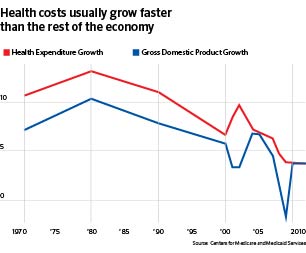

In recent years, there has been an unprecedented slow-down in healthcare costs. For the last four years, healthcare costs grew at about the same percentage as the overall economy. This is in contrast to the last two decades where growth in healthcare expenditures generally exceeded overall GDP growth (see Graph 1).19 Most commentators attribute the recent trend to the recession, as people were less able to afford needed healthcare services as they lost their job or received cuts in hours and pay. And there is significant debate on the ACA’s initial impact. But as the New Republic’s Jonathan Cohn points out:

if the law’s ability to hold down the cost of medical care remains very much an open question, its effect on the budget seems pretty clear, at least for the near term. It is reducing the deficit. Conservatives keep insisting the opposite, calling the Obamacare a budget-buster. But every time the CBO makes a new estimate, it reaffirms its judgment that the law will save more money than it spends. In fact, the projections of budget savings are getting bigger, not smaller, with time.20

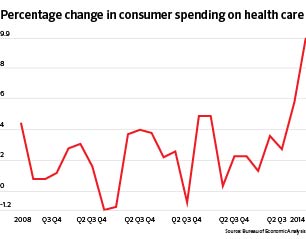

It also should be noted that the recent slowdown in healthcare costs might not hold as the economy recovers from the 2008 low point. The first quarter of 2014 saw healthcare spending jumped by 9.9% (see Graph 2).21

It should be clear that cost control is the guiding principle of the ACA. But what impacts will this have on healthcare restructuring currently underway? What I hope to make clear is that the ACA: 1) helps facilitate and expand for-profit healthcare while consolidating profitable healthcare services; 2) restructures Medicaid and Medicare reimbursement to healthcare providers, resulting in the acceleration of community hospital closures, thus deepening the public sector hospital crisis, and facilitates steep cuts to other “un-profitable” services like behavioral health, resulting in severely-diminished access to care for millions; and 3) incentivizes deskilling and the Taylorization of healthcare workplaces alongside broadside attacks on unionized workforces.

Graph 1

Graph 2

Many of these processes have been underway for years, if not decades. But I would argue that the ACA signifies a categorical leap in the longer-term trend of the neoliberal reorganization of healthcare. For the healthcare sector, the ACA offers a clear opportunity to quarantine the liability of patients whose bank accounts or healthcare plans don’t provide enough revenue, and at the same time push healthcare out of the locations where profit margins aren’t as great, for instance the more unionized and better paid staffs of hospitals. For capital outside of the healthcare sector, the ACA promises cost containment and cost shifting from their payroll departments towards employee out-of-pocket expenses and government subsidies.

While Part 2 of this series will look more closely at the private health insurance industry, suffice is to say that the ACA amounts to an extraordinary devotion of taxpayer dollars to subsidize this for-profit industry. Many estimate that ACA will deliver approximately 20 million new customers to insurance companies in the next two years and perhaps another 20 million after that. Using a (very) low estimate of $200 per month for an average per-person subsidy, when enrollment fully takes shape, insurance companies can count on 4 billion per month in money from the federal government. This, of course, has spawned an explosion of investment in health insurance. In New York State, a private venture capitalist has raised $200 million for a new company called Oscar, while the “non-profit” North Shore-Long Island Jewish hospital system backed another new company called Care Connect to the tune of $27 million.22

In the end, hundreds of billions of federal taxpayer dollars will be used to subsidize companies that continue to have economic interests diametrically opposed to the healthcare needs of their customers, sometimes known as patients. Even though there are important regulations built into the ACA that require insurance companies to devote between 80-85 percent of their revenue to direct patient care (called the Medical Loss Ratio) and regulate their previous barbaric practices of not covering pre-existing conditions, there will still continue to be billions in healthcare dollars wasted on administrative costs and profits. With all of the federally facilitated competition happening on the healthcare exchanges, it is estimated that insurance companies will spend close to one billion dollars on marketing alone.23

Beyond corporate subsidies, one of the most profound changes is the way the ACA reconfigures payments to healthcare providers. Medicaid, Medicare, and now most private insurance companies will pay hospitals, nursing homes, and doctor’s offices in bundled payments based on the average cost of the care for a particular patient as opposed to reimbursing for a particular service provided. These bundles will include payment for primary care, hospital care, home care, and other services. The ACA has created a new form of healthcare organization called Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) that are meant to streamline this process. Existing institutions can decide to become an ACO or new ACOs will be created. The ACOs are setup to mimic bundled reimbursement, with the various types of healthcare providers under one organizational roof. Since only one payment is dispersed to split however many different ways, individual and smaller-scale healthcare providers are at a decided disadvantage. For every form of healthcare provider, bundled payments and the ACO model add considerable pressure to provide fewer services or otherwise cut services that don’t directly relate to measurable healthcare outcomes. The other pressure for healthcare providers will be to avoid sicker or complicated patients because reimbursement is based on the average cost.

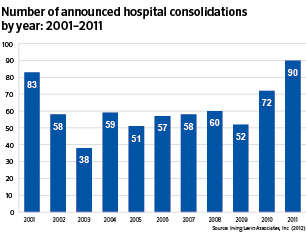

Bundled payments will also significantly incentivize consolidation and mergers. This is happening at a highly accelerated rate. In October of 2013, two of the largest for-profit hospital systems nationally, Tenet and Vanguard Health merged.24 In the summer 2013 in New York City, Mt. Sinai and Continuum, two non-profit hospital systems, merged to create the largest healthcare system in the city, consciously “positioning the new system to take advantage of coming changes under the federal health care law.”25 Here is where the first contradiction of the ACA’s cost containment strategy emerges. By numerous studies, mergers and consolidation increases cost because larger entities can use their leverage to charge more for services, usually at rates between 20 percent and 40 percent higher than average.26 As liberal policy wonks Phillip Longman and Paul S. Hewitt observe,

Clearly, bigness in healthcare can lead to efficiency and lower prices. But just as in other industries, bigness in healthcare can also lead to monopolistic pricing and other abuses. And sadly, rampant, unregulated monopolization of healthcare is what has been going on in virtually every medical community in America, as hospitals, doctors, and other providers combine in ways that drive up costs for everyone without improving care.27

As the federal government and insurance companies try to pay less, hospitals will leverage to try and charge more, ensuring either higher reimbursement, more out of pocket costs, or both. In healthcare executive parlance, “increasing margin pressure from government and commercial payers and escalating intensity of competition for healthcare dollars indicate that acute care mergers and acquisitions will happen with greater frequency and complexity in the near future.”28 The ACA is widely understood to be a key factor. In a report titled “What Hospital Executives Should Be Considering in Hospital Mergers in Acquisitions,” the authors note “many observers believe that the increased prevalence of consolidations experienced in 2010 and 2011 (72 and 90 respectively) represent a material increase in overall transaction activity, correlated in part to hospital preparation for reform provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.”29

Alongside the creation of ACOs, the ACA directly and indirectly is creating a frenzy of federal and private investment in healthcare companies whose sole purpose is to figure out how to provide the same service for less cost. To provide an incubator for these new enterprises, the ACA creates a well-funded department within the Center for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS)—the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation. Hundreds of healthcare companies, both new and already existing, have received hundreds of millions of dollars in federal money to develop business plans with the goal of one day landing a lucrative Medicare contract if they can provide less-costly services.30

If the ACA is incipient communism, Wall Street certainly did not get the memo. “[The ACA is] not a government takeover of medicine. It’s the privatization of health care. If you took George H. W. Bush’s health plan and removed the label, you’d think it was Obamacare.”31 This is what Tom Scully pleaded to a group of (mostly Republican) investors as he tried to drum up cash for his own healthcare startup. And Mr. Scully should know. Not only is he a highly successful private equity investor and knows when there’s money to be made, he was also a key architect of George H. W. Bush’s healthcare policy and head of the CMS under George W. Bush. When working for Bush II, he helped create Medicare Part D, which was the last major federal initiative that funneled billions of federal dollars to the profit margins of the health insurance and pharmaceutical industries

He goes on, “with the right understanding of the industry, private-sector markets and bureaucratic rules, savvy investors could help underwrite innovative companies specifically designed to profit from the law. Billions could flow from Washington to Wall Street.”32 Mr. Scully then tempts his audience with hopes that one day, they too could become an “Obamacare billionaire.”33

Private equity investment in healthcare predates Obamacare, but it is clear that a significant expansion is underway. It’s therefore worthwhile to briefly take a look at what private equity (PE) investment does to healthcare delivery. Currently, PE firms own half of all for-profit hospitals.34 In 2011, the value of private equity deals reached $30 billion, double the previous year.35 “For-profit firms emphasize surgical and acute care services, and cardiac and diagnostic services, while non-profit hospitals often provide less lucrative care such as mental health services, drug-and-alcohol treatment programs, and trauma-and-burn centers.”36

PE investment firms are best understood as the International Monetary Fund of the healthcare sector, offering financial bailout for struggling hospitals, then demanding structural adjustment (i.e. elimination of certain services) in order to see a return on their loan/investment:

The growing appetite for hospital takeovers by PE firms has its roots in the ongoing struggle for survival experienced by many hospitals. Hospitals—particularly small, community hospitals and those serving poor populations—are under intense pressure due to declining Medicare/Medicaid reimbursement rates, new government demands for technological upgrades, increasing numbers of under- and uninsured patients, and restricted access to credit markets.37

PE firms like the notorious Bain Capital, Cerebus, and The Blackstone Group (who backs Vanguard Health) buy up struggling hospitals, often eliminating less-profitable services, and using the cost savings to recoup fees and dividends, often increasing the debt of the hospital before it’s sold off at a later date.38 The vultures are circling the carcasses. In a state with a pronounced hospital closure crisis, Governor Andrew Cuomo, in both 2013 and 2014, has attempted to bring in private-equity firms into New York for the first time (see page 52 for more details).

Another key area of private investment that Obamacare directly funds is information technology (IT). You need look no further for the mark of a neoliberal reform than an endorsement from New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman, who envisions the ACA creating a “healthcare Silicon Valley.”39 The ACA mandates that every doctor’s office and hospital alike conform to myriad of filing requirements, mostly related to tracking healthcare outcomes and reimbursements, and all to happen electronically. It also provides funding with taxpayer money for those institutions to pay for these upgrades. In addition to $19 billion in the 2009 federal stimulus package devoted to healthcare IT, the ACA includes a funded mandate that “any hospital that doesn’t have ‘meaningful use’ of IT by 2015 will face a cut in reimbursements . . . at a cost of up to $30 million per hospital—and that’s without the extra IT staff they need to hire.”40 So healthcare IT companies like Epic are getting paid tens of millions per hospital from the federal government to perform this work.

Then of course there’s the technology necessary to run the healthcare exchanges, which infamously failed, and continued to fail for several month after the October 1, 2013 launch date. The complexity of the legislation itself is primarily to blame, with the need to communicate unmanageable amounts of data between would-be customers, the federal government, and insurance companies. But no less than 55 different companies were contracted to implement the online exchanges, assuredly adding to the chaos and confusion.41

This ACA enrollment debacle is emblematic of the overly complicated and wasteful market-based solutions that have never worked in our healthcare system. There is one fundamental reason why this is true. The more money and resources you take away from providing direct care to patients, whether in the form of profits, administrative costs, advertising, or information technology, the less healthy (and more costly) people are likely to be. The rollout debacle reveals another more general contradiction—that of the unnecessary complexity and corruption inherent in public-private partnerships of which, perhaps even more than charter schools, the ACA may stand as the grandest of examples. As Alex Gourevitch argues,

These ‘partnerships’ reveal a special viciousness—they are harder to manage. That is because, as (Robert) Kuttner notes elsewhere, “a layer of complexity is added because of the need to supervise and monitor the private vendor. Corruption is invited, because it pays the vendor to offer disguised bribes to the public officials in charge of the contract.” The standard response, moreover, is to try to expertly manipulate the incentives of the market in which these entities operate, itself an impossible task that introduces only more complexity and confusion.

The deepest irony, then, of the neo-progressive vision is that its faith in expert management is belied by its lack of belief in the public. Indeed, the reliance on private contractors, management consultants, financial executives, isn’t just a sign of corporate influence, but also of a skin-deep confidence in their own powers. It is not so much the product of corporate corruption as it is a vision of politics that invites such corruption, beginning with a natural and spontaneous belief in the intellectual prowess of the managers, CEOs, and Wall Street financiers upon whom they end up relying.42

Patient advocacy groups, or healthcare providers did not write the ACA with patient’s needs in mind; healthcare executives wrote it for healthcare executives. In 2012, for the first time, the healthcare sector became number one in money spent on lobbying—$243 million—outspending the FIRE (finance, insurance, and real estate) industries.43 And they got what they paid for. Big Pharma, for instance, was able to stave off any significant price controls on their infamously hyper-inflated life-saving products:

Costly brand-name biotech drugs won 12 years of protection against cheaper generic competitors, a boon for products that comprise 15 percent of pharmaceutical sales . . . Lobbyists beat back proposals to allow importation of low-cost medicines and to have Medicare negotiate drug prices with companies. They also defeated efforts to require more industry rebates for the 9 million beneficiaries of both Medicare and Medicaid, and to bar brand-name drugmakers’ payments to generic companies to delay the marketing of competitor products.44

Closing hospitals and boosting profits

Up until the 1980s, almost all hospitals were either non-profit or public. But as the cost of new technology, medical supplies, and pharmaceuticals rose, as well as the population of uninsured patients, smaller community hospitals, funded primarily through Medicare, Medicaid, and philanthropy, began to struggle financially. In 1983 Medicare drastically changed its payment structure, for the first time tying standardized payments to specific diagnoses (known as Diagnostic Related Groups or DRGs). This forced many community institutions to become financially vulnerable and consolidate into larger systems. Craig B. Garner, in an analysis of community hospital closures and consolidation, paints this picture:

Across the nation, America’s community hospitals are under siege. Once considered indispensible to our healthcare system, the twenty-first century finds the local hospital fighting an uphill battle against a convergence of factors that favors the sharing of resources by multiple facilities. Rising healthcare expenses, challenging regulatory hurdles, and a reimbursement structure in the midst of transition all bear some responsibility for the obstacles faced by today’s community hospital. Nowhere is this phenomenon more pronounced than in California, where regular hospital closings amid an ever-growing population stand as incentive for remaining hospitals to team up (or remain teamed up) under the potentially false notion that in modern American healthcare, there is safety in numbers.45

In this climate, investors see an opportunity, particularly if they can reshape hospital care to expand the more profitable services and eliminate the less profitable. For-profitization has experienced two previous waves. The first was around the time of the DRG transition in Medicare payments, the second amidst a brief speculative bubble in healthcare in the mid-1990s that collapsed under its own weight, exemplified by a widespread fraud investigation of the most rapacious of the for-profits—Columbia/HCA.46

The ACA could initiate a third wave, although for-profitization is likely to happen more often by peeling off services from non-profit or public hospitals and operating them as separate entities, whether they continue to be physically located in the same hospital building or not. The privatization of dialysis services in New York City’s public hospital system is but one of many examples. Currently, for-profit hospitals make up a full 40 percent of hospital care nationwide.47 In New York State, Governor Cuomo has attempted to bring in private equity firms into healthcare for the first time in the state’s history.

New York is the last frontier for PE investment and for-profit hospital chains as it is the last state where for-profit hospital care is currently barred by law through its Certificate of Need (CON) regulatory process. New York is also facing a community hospital closure crisis, currently centered in Brooklyn and some upstate regions. Since 2000, New York City alone has seen 19 hospitals close. At the start of 2013, at least two additional facilities, Long Island College Hospital and Interfaith Hospital, were slated for closure. But unexpected and thus far effective resistance emerged in the form of a major community-labor alliance between the New York State Nurses Association, the Service Employees International Union 1199, and several physician groups, neighborhood associations, and other community organizations. Mounting successful legal challenges and street actions, sometimes several per week of both, the coalition kept both hospitals open for over a year. Interfaith is still standing, while LICH was closed after a legal settlement reached between the coalition and the former operator of the hospital, the State University of New York, that allowed the coalition to have some influence as to whether a hospital will be rebuilt on the same site.

Governor Cuomo has twice attempted to use the financial troubles of Brooklyn hospitals as a justification for the entry of for-profit hospitals into the state for the first time. Attached to his budget proposals in 2013 and 2014 were two for-profit “pilot programs” specifically planned for Brooklyn and an unnamed upstate location. Both times the measure was defeated due to pressure exerted by NYSNA and 1199. Anne Bové, a registered nurse at Bellevue Hospital and secretary of NYSNA, aptly summed up the stakes, “Advocates for public health have argued that for-profit operations would mainly benefit stockholders and investors by cherry-picking patients and procedures, sending the poorest and uninsured patients to other overwhelmed hospitals, and shredding a frayed safety net. Nurses, caregivers, and patients should be the ones making decisions about patient care—not hedge funds and private equity investors.”48

The ACA exacerbates this crisis in community hospital care, thus, in some cases, facilitating the transition of non-profit hospitals to for-profit hospitals. Already in the first quarter of 2014, there have been seven hospital closures across the country.49 Community hospitals rely disproportionately on Medicaid and Medicare for their funding. Within Medicare and Medicaid, there’s also a specific program called Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) funding, commonly referred to as Charity Care funding, in which monies are allocated to hospitals that provide lower cost or free care to the uninsured or underinsured. Under the ACA, Medicare funding is decreased and restructured, Medicaid is also restructured, and DSH funding is eliminated. In addition, the ACA now requires extensive documentation of how these hospitals expend resources on the uninsured. “If charity hospitals don’t comply with labyrinthine filing requirements they are forced to become for-profit and lose their tax-exempt status.”50

Lack of healthcare access related to community hospital closures is a significant and overlooked element to the overall healthcare crisis in the US. Since declining Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements, as well as DSH funding cuts, are a significant factor, it will be necessary to go into more detail about the particular upcoming changes.

Medicare and Medicaid under the ACA

Over $700 billion will be cut from Medicare over the next ten years.51 These are the cuts that the ACA imposes as it reduces the percentage of payment increases so they intentionally don’t keep up with inflation. In addition, what were known in 2013 as the sequestration cuts are carving another 2 percent from Medicare’s entire budget in 2014 and possibly in perpetuity.52 The Kaiser Foundation estimates that the cuts to hospitals will be drastic:

The July report from CBO and JCT [Congress’ Joint Committee on Taxation]—in explaining where some of the biggest reductions would occur—found that hospital reimbursements would be reduced by $260 billion from 2013-2022, while federal payments to Medicare Advantage, the private insurance plans in Medicare, would be cut by approximately $156 billion. Other Medicare spending reductions include $39 billion less for skilled nursing services; $66 billion less for home health and $17 billion less for hospice.53

What may be at least as significant as the spending cuts is that under the ACA, Medicare will move to a merit-pay system for hospitals. “For the first time in history, Medicare will soon track spending on millions of beneficiaries, reward hospitals that hold down costs, and penalize those whose patients prove most expensive.”54 If a hospital spends less than the average amount Medicare usually pays for a particular patient, then that hospital will receive a bonus, if they spend more than the average, they will be penalized. Medicare penalties will also be imposed for higher than average readmission rates, higher rates of “preventable” patient care issues like bedsores, and hospital acquired infections, medication errors, and other injuries.55 By CMS’s own assessment, 25 percent of hospitals could lose $3.2 billion over ten years.56

Healthcare and education reform

A comparison

There are a number of ways in which reforms implemented under the ACA mirror the ideology and methodology embedded in education reforms like No Child Left Behind and Race to the Top.

The dynamic is similar and usually looks like this: starve an institution of resources, set a standard that is not easy to meet given available resources, blame said institution for not meeting the standard, then force said institution to close resulting in further decreased access to services and worsening the overall problem, leading to increased class and racial inequalities.

Both education and funding to hospitals have been cut by federal, state, and municipal governments in various ways, especially in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent state and municipal budget crises. In education this process has happened unevenly, and usually by shifting resources to testing, administration, and charter schools. In healthcare it’s largely through state reductions in Medicaid spending and the Medicare cuts mandated in the ACA. Because of bundled-payments and reduced reimbursements from Medicaid and Medicare, hospitals may look to avoid high-risk patients so as to escape penalties.57 These patients, especially if they have Medicaid or Medicare, will be ushered into public hospital systems or other safety-net institutions. This will then set up these institutions for further penalties and financial instability. The same dynamic is happening with the introduction of charter schools, where the better students are selected and children who have trouble with standardized tests or have behavior issues are bounced back to the public schools, which are then rated poorly and sometimes closed. Privatization is a key element of both processes. Whole school systems (Philadelphia, New Orleans) have been auctioned off to charter school systems. In healthcare, public services, or portions of public services such as dialysis services in New York City, have been sold off, and many, formerly non-profit institutions, left vulnerable by the ACA, will be feasted on by for-profit hospital systems and private equity firms.

Reforms in both sectors fetishize technology and data-driven evaluation. Considerable resources in education have been devoting to testing and teacher evaluation schemes so as justify school closures, charterization, and the evisceration of teacher tenure. The ACA devotes considerable public funds to expanding electronic medical records so as to facilitate evaluating hospitals in order to determine funding. These systems will have the added benefit of monitoring staff (mainly nurse) productivity. There’s also scapegoating imbedded in both forms of restructuring. In education it concentrates blame on teachers for education inequality. In healthcare, the implicit idea is that mechanisms need to be in place to combat the overconsumption of care. Both deflect from the underlying social conditions and inequalities that actually cause healthcare and educational disparities, and both were created and advocated for by millionaires and billionaires and will ultimately serve their material and ideological interests.

Because it will have an impact on their bottom line, hospital administrators are joining the chorus of critics. Kenneth E. Raske of the Greater New York Hospital Association told the New York Times that the Medicare penalties within the ACA “tends to discriminate against inner-city hospitals with large numbers of immigrant, poor, and uninsured patients.”58

More recently, CMS has imposed what it is calling the “two midnight rule” on hospitals. This means, hospitals will not receive a reimbursement for an in-patient hospital stay unless the patient stays in the hospital for two midnights. For large hospitals, this could amount to a $20-30 million dollar decrease in revenue. For New York City’s public hospital system, the largest in the country, just this rule change alone amounts to a 16 percent reduction in the total in-patient revenue for the entire system.59

Medicaid, the federal healthcare program for the poor, is being expanded under the ACA in what was to be most significant positive component of the ACA. But the June 2013 Supreme Court ruling allowed states to opt out of expanding Medicaid creating massive pool of uninsured patients who will still need to seek care in hospitals. It is these same hospitals that are being starved of revenue by other changes in the legislation and subsequent regulations. In fiscal year 2012, 30 states reduced their Medicaid payments to healthcare providers in some form or another, and in fiscal year 2013 15 states did so.60 According to Kaiser Health News,

Illinois cut enrollees to four prescriptions a month; imposed a copay for prescriptions for non-pregnant adults; raised eligibility to eliminate more than 25,000 adults and eliminated non-emergency dental care for adults. Alabama cut pay for doctors and dentists 10 percent and eliminated coverage for eyeglasses. Florida cut funding to hospitals that treat Medicaid patients by 5.6 percent—following a 12.5 percent cut a year ago. The state is also seeking permission to limit non-pregnant adults to two primary care visits a month unless they are pregnant, and to cap emergency room coverage at six visits a year. California added a $15 fee for those who go to the emergency room for routine care and cut reimbursements to private hospitals by $150 million. Wisconsin added or increased monthly premiums for most non-pregnant adults with incomes above $14,856 for an individual.”61

In states like New York, Medicaid expansion was accepted but because New York had already provided close to the same Medicaid coverage that the ACA expands, very little new revenue is expected from this change. The bulk of Medicaid patients in New York City are seen in the public hospital system, officially called the Health and Hospital Corporation (HHC). HHC has been suffering heavy revenue losses for years and will now face increased patient volume from other closing institutions, increased overcrowding, patient wait times, and stress from bare-bones staffing levels.

In short, in many places, especially in the north, Medicaid access will be increased in terms of coverage, but decreased in terms of access to healthcare facilities. In the south, patients will remain uninsured and have to rely on emergency care in safety-net hospitals that are seeing severe cuts in their Medicare revenue and are also closing. For instance in Georgia, three rural hospitals have already closed in 2013, with 15 more teetering on the brink of bankruptcy.62 And Medicaid is also penalizing institutions for adverse outcomes:

The Medicaid list of what is preventable mirrors the Medicare list, which includes transfusing the wrong blood type; falls that result in dislocation, fractures, or head injuries; burns and electric shocks; catheter-associated urinary tract infections; surgical site infections after bariatric surgery or coronary artery bypass; and manifestations of poor glycemic control. Since Medicare enacted its policy of not paying for preventable events, private insurers have begun to do the same.63

Medicare and Medicaid have tremendous leverage to shape the healthcare system. But instead of using these programs to expand public services and curtail inflation in, say, the pharmaceutical industry, the opposite is happening.

DSH funding

The continued existence of mass numbers of uninsured exacerbates another major funding cut contained with the ACA, the virtual elimination of DSH funding. Because the ACA was pitched as a plan for universal coverage, the administration justified the elimination of DSH funds with the rationale that hospitals won’t need additional money to provide care for the uninsured.

Unfortunately, the combination of unaffordable premiums and the lack of Medicaid expansion in many states will result in tens of millions remaining uninsured. This rationale also does not consider the 12 million undocumented immigrants who are not covered by the healthcare exchanges, Medicare, or Medicaid (except for under special “emergency” circumstances). This is likely to increase the tension between hospitals and their uninsured and undocumented patients.64 The cuts are severe. Over $36 billion in DSH funding to hospitals is projected to be culled from Medicare and Medicaid by 2019. For some hospitals, this could amount to a full 12 percent of their overall Medicaid reimbursement.65

Between federal Medicare cuts, additional sequestration cuts, the two-midnight rule, and the elimination of DSH funding, survival for hundreds of hospitals dependent on Medicare and Medicaid has been thrown into question. There are also untold billions that won’t be paid to hospitals because patients will continue to be unable to afford the out-of-pocket costs for incredibly expensive medical care. This will certainly be true for the millions left uninsured by the ACA who will continue to go into bankruptcy, but it’s also true for the people who will sign up on the exchanges. For example, the Bronze plans (i.e. the most affordable, bare-bones coverage) provided under many exchanges cover only about 60 percent of all healthcare costs on top of high deductibles.66 If people can’t afford to pay the out-of-pocket costs, the hospitals will absorb the cost. And many will refuse. The New York Times reported in May that, “Hospital systems around the country have started scaling back financial assistance for lower- and middle-income people without health insurance, hoping to push them into signing up for coverage through the new online marketplaces created under the Affordable Care Act.”67

As previously noted, the decrease in revenue streams to hospitals leaves them vulnerable and has created the conditions for the spike in mergers and acquisitions by larger hospital groups and chains. An AARP bulletin discussed the merger frenzy: “More than 100 hospital deals took place in 2012, double the number just three years earlier. Of the 5,724 hospitals in the United States, about 1,000 will have new owners in the next seven years or so, predicts Gary Ahlquist, a senior partner with the consulting firm Booz & Company. And hospitals that want to remain independent will have a harder time staying afloat.”68

But many will simply close. Urban safety-net hospitals and rural hospitals dependent on federal assistance are particularly vulnerable. For rural hospitals, there’s currently a proposal to dispense of their federal subsidy. Many rural facilities are designated as “critical-access hospitals” (CAHs) and receive enhanced Medicare payments in order to survive in areas of lower patient volume but where access to healthcare is desperately needed. In August of 2013, the Department of Healthcare and Human Services Office of the Inspector General (HHSOIG) proposed that CMS cut this enhanced payment to 846 of these facilities. The report states, “If CMS had decertified CAHs that were 15 or fewer miles from their nearest hospitals in 2011, Medicare and beneficiaries would have saved $449 million.”69 Alan Morgan, CEO of the National Rural Health Association said the HHSOIG cuts “would effectively kill rural healthcare.”70

Urban safety-net hospitals are faring no differently. We now are discussing the phenomenon of hospital deserts. Fifty years ago, Detroit had 42 hospitals serving approximately 1.5 million people. There are now four, serving about 700,000.71

Healthcare restructuring in New York

New York State, perhaps because of its extensive public hospital system and large unionized workforce, is at the epicenter of healthcare restructuring both prior to and as a result of the Affordable Care Act. There’s been a highly organized effort to systematically close hospitals, bring in private equity firms, and reduce public sector services through privatization and budget cuts.

New York State is the last frontier for PE investment and for-profit hospital chains as it is the last state where for-profit hospital care is currently barred by law through its Certificate of Need (CON) regulatory process. NY is also facing a community hospital closure crisis, currently centered in Brooklyn and some upstate regions. Since 2000, New York City alone has seen 19 hospitals close. At the start of 2013, at least two additional facilities, Long Island College Hospital and Interfaith Hospital, were slated for closure. But unexpected and thus far effective resistance emerged in the form of a major community-labor alliance between the New York State Nurses Association, the Service Employees International Union 1199, and several physician groups, neighborhood associations, and other community organizations. Mounting successful legal challenges and street actions, sometimes several per week of both, the coalition kept both hospitals open for over a year. Interfaith is still standing, while LICH was closed after a legal settlement reached between the coalition and the former operator of the hospital, the State University of New York, that allowed to have some influence as to whether a hospital will be rebuilt on the same site.

Governor of New York, Andrew Cuomo, has twice attempted to use the financial troubles of Brooklyn hospitals as a justification for the entry of for-profit hospitals into New York state for the first time. Attached to his budget proposals in 2013 and 2014 were two for-profit “pilot programs” specifically planned for Brooklyn and an unnamed upstate location. Both times, the measure was defeated due to pressure exerted by NYSNA and 1199. Anne Bové, a registered nurse at Bellevue Hospital and Secretary of NYSNA, aptly summed up the stakes, “Advocates for public health have argued that for-profit operations would mainly benefit stockholders and investors by cherry-picking patients and procedures, sending the poorest and uninsured patients to other overwhelmed hospitals, and shredding a frayed safety net. Nurses, caregivers and patients should be the ones making decisions about patient care—not hedge funds and private equity investors.”72

State cuts to Medicaid in New York State imposed by Governor Andrew Cuomo throughout the 2010s, some through the Medicaid Redesign Team he created, have helped foment a rash of closures, mainly to safety-net community hospitals. Specifically, Cuomo capped the increase of Medicaid spending at 2 percent, which is well below the rate of medical service inflation. Gov. Cuomo then continued to act on recommendations made by the Commission on Health Facilities for the 21st Century, more commonly known as the Berger Commission, which was set up by Governor Pataki to organize hospital closures in New York State starting in the mid-2000s. The commission’s namesake, Stephen Berger, is an investment banker by trade but is famous for overseeing widespread austerity as a solution to New York City’s fiscal crisis in 1975-6 as the Executive Director of the Emergency Control Board.

In just six years, the Berger Commission helped close 18 hospitals throughout NY state, 12 of them within the five boroughs of New York City.73 What Cuomo and Berger couldn’t get to, the Medicare and DSH funding cuts just may. The center of the NYC hospital crisis has shifted to Brooklyn, where the previously mentioned battle to save LICH and Interfaith is currently playing out. More are expected in the next two years. As Danny Katch reported, in an article in this journal about the end of the Bloomberg years, “if Brooklyn loses three more hospitals as expected, the borough of two and a half million people will be left with only five emergency rooms. If you’re wondering what that will look like, the answer is Queens, which lost 30 percent of its hospital beds per resident from 2006 to 2008, resulting in an average wait time of seventeen hours to be given a bed in one major hospital.”74 In a borough inundated by patients during Superstorm Sandy, having only five emergency rooms is a public health crisis waiting for an opportunity to become a full scale meltdown. Another hospital slated for closure in NYC is the very last healthcare facility on the peninsula known as the Far Rockaways where residents were notoriously stranded during the storm without assistance of any kind. Activists with Occupy Sandy and nurses from NYSNA provided the only medical attention for many residents for weeks.75

Of course, there’s an added incentive for hospital closures in NYC – real estate. It is widely thought that the owners of LICH, the State University of New York, wants to sell it off to private developers.76 This already happened to St. Vincent’s Hospital in Greenwich Village. When it closed in 2008, it was converted immediately to luxury condos.77 In aftermath of the current merger between Mt. Sinai Medical Center and Contiuum, Mt. Sinai is discussing selling off parts of St. Luke’s hospital near Harlem to real estate developers.78

Another battleground that NYC remains in the center of is the fight preserve public hospital care in the United States. Many public hospital systems throughout the country have consolidated into one or two facilities, or collapsed completely. Detroit’s last public hospital closed in the early 1980s. NYC is home to the largest remaining system in the country, HHC, with 11 major facilities and a network of clinics. But Cuomo’s Medicaid cuts, Bloomberg’s privatization schemes, and the ACA’s Medicare and DSH cuts are taking an extreme toll on the system. At the HHC public meetings in the fall of 2013, President Alan Aviles provided a bleak picture of HHC’s financial situation in the wake of the ACA. “Under the Affordable Care Act, beginning in 2014 the federal government will make significant reductions in supplemental Medicaid and Medicare funding that supports public hospitals. These cuts increase dramatically by 2017 and ultimately could reduce HHC’s federal funding by more than $325 million annually.”79

As to the cuts already imposed by Governor Cuomo, Aviles stated, “Medicaid cuts and reforms in the State’s budget will reduce HHC’s reimbursements from the state by more than $50 million this coming year. Over the past five years, HHC has absorbed cuts that now total an astonishing $540 million annually.”80 Bloomberg had already sold off HHC’s inpatient dialysis services to private contractors in 2012, in addition to privatizing laundry, nutrition, and environmental services in years prior. Whole sections of the system are constantly under threat. The entire Labor and Delivery unit at North Central Bronx Hospital was shut down in August, 2013 due to unsafe staffing levels, with only a promise to reopen in the fall of 2014. Aviles boasted that HHC generated millions in savings by cutting 3,700 jobs in the last two years, mainly through attrition.81

The mental healthcare crisis and the ACA

Not all hospitals will close, of course. But all hospitals, for-profit, non-profit, and public hospitals, will feel pressure to cut costs, and in many cases drastically. Two key strategies administrators seem to being using are to eliminate unprofitable services and to cut labor costs. One of the most significant unprofitable hospital services is mental healthcare.

There is an ongoing mental healthcare crisis in this country, but the number of mental healthcare beds is rapidly declining with no subsequent expansion in outpatient services. Often, untreated mental illness, especially severe mental illness, ends up with the would-be patient entangled in the tentacles of the criminal injustice system in the era of mass incarceration. In fact, one could argue that we’ve now seen the emergence of a hospital-closure-to-prison pipeline alongside the drastically increased use of solitary confinement.

In 2008, the Treatment Advocacy Center estimated that the US hospital system is deficient of at least 100,000 inpatient behavioral health beds, resulting in “increased homelessness, emergency room overcrowding, and use of jails and prisons as de-facto psychiatric hospitals.”82 The cuts imbedded in the ACA will make this worse. Already in 2013, the 127-bed psychiatric hospital Holliswood in Queens closed its doors.83 Interfaith Hospital in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn has 160 behavioral health beds and it’s on the chopping block.84

At the same time, prison facilities on Riker’s Island have seen a spike in patients forced into solitary confinement. In the last six years, the number of “punitive segregation” beds at Riker’s increased 62 percent.85 According to the New York Times, “of the people put into solitary confinement, high percentages have mental illness. On July 23, for instance, 102 of the 140 teenagers in solitary were either seriously or moderately mentally ill, according to a consultant’s report prepared for the city’s Board of Correction.”86

The largest mental healthcare facility in Illinois is the Cook County jail. And they’re also running out of room. Cermak Health Services, the company charged with running the mental health facilities at the jail says it’s currently at 130% capacity. “I have guys sleeping on the floor,” according to the sheriff.87 Mentally ill inmates make up approximately 25-30 percent of the prison population at Cook County at any given time. A report from the National Alliance on Mental Illness found that from 2009 to 2012, mental health spending in Illinois was cut by close to $200 million.88

Nevada found a better solution. Put them all on a bus. From 2008-2013, according to a lawsuit filed by the state of California, Nevada hospitals sent over 1,500 mentally ill patients on one-way bus rides to Sacramento and San Francisco. “While some of the patients were given the names of shelters or told to dial ‘911’ upon arrival in California, a substantial number were not provided any instructions or assistance in finding shelter, continued medical care, or basic necessities in the cities and counties to which they were sent.”89 For its part, Nevada officials do not deny the practice, only disputing that they did, in fact, provide adequate follow-up care instructions.

Hospitals will continue to resort to these horrific measures as their revenue streams and profit margins get smaller and smaller. Another way to reduce operating costs is to slash labor costs. According to Challenger Gray, in October of 2013 “health care providers announced more layoffs than any other industry last month—8,128—largely because of reductions by hospitals.”90 Vivian Yaling Wu, professor of healthcare economics and finance at the University of Southern California, estimates that the ACA will reduce per-patient hospital revenue by $321, forcing hospital to spend less. A study in Health Affairs shows that 60 percent of hospital spending decreases is coming from labor costs. Another study in Health Services Research found that “hospitals eliminate 1.7 full-time jobs for every $100,000 drop in Medicare revenue. Nurses accounted for one-third of the reduced workforce.”91

In addition to outright layoffs, another way to reduce labor costs is through cheapening the labor force through deskilling and automation. Healthcare in general and hospital care in particular is one sector you would think should be morally impervious to such forces because of the obvious danger to patients by having less-skilled practitioners providing patient care. But that is precisely what is happening. Instead of primary care doctors, some propose the creation of the title “Primary Care Technicians,” workers who do not have medical degrees or are certified as nurse practitioners, but who are trained to handle routine primary care “tasks”.92 In Connecticut, the state legislature considered a proposal to change licensing laws so that unlicensed personnel can administer medications.93

Then there are the robots. In January of 2013, the FDA approved the first bedside robot for use in hospitals, complete with an interactive iPad touchscreen where you can interact remotely with a physician or nurse while you’re recovering from surgery.94 Another far more widespread example of automation in healthcare is the massive expansion of electronic medical records, ostensibly so that the work of healthcare provision can be routinized and measured. As discussed previously, the ACA provides billions in investment in healthcare information technology. Deskilling and automation go hand-in-hand. Healthcare IT often lays the groundwork for the argument that less credentialed (and less expensive) employees can “check a box” just like anyone else. By utilizing technology to Taylorize healthcare using time studies and efficiency programs like LEAN (invented by Toyota for the auto industry now currently being used by HHC), hospitals are attempting to find ways to do “more with less.” Indeed, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that between December of 2013 and February of 2014 hospital employment fell for the first time in 20 years, even as employment in the healthcare sector overall continued to grow.95

Of course, both the patient and the healthcare provider suffer dearly from these processes. A review of nursing literature from 2000–09 found that nurses have widespread dissatisfaction with electronic medical records and are concerned about dangerous alterations in nature of nursing care “resulting in a potentially negative impact on individualized care and patient safety.”96NY Nurse, the magazine of the New York State Nurses Association, states:

Routinized care turns nursing into something of an assembly line. It requires nurses to turn off their good judgment, thereby deskilling the profession. In theory, IT systems are tools that help caregivers deliver quality care. In practice, they’re instruments that help hospital administrators put management control over nursing practice, and expertise and profit before patient care.97

Working under severe staffing shortages means several things for those who remain. One is that you often have to do the jobs that several others used to do. Nurses in Tennessee were forced to clean floors in addition to administering medication and assessing their patients.98 Nurses have reported widespread staffing shortages for years, if not decades. But the ACA promises to bring this staffing crisis to fever pitch, with both layoffs and the incidence of severely-overworked hospital staff likely to increase. Major legislative initiatives such as nurse-to-patient staff ratios are now a must win fight for nurses. Nurses in Massachusetts have introduced a referendum and New York has been building momentum for a Safe Staffing bill since last spring. Currently, California is the only state with comprehensive nurse staffing regulations in place. But, as critical as this fight is, staffing ratios don’t solve the funding problem, especially for struggling community and public hospitals. This fight has to happen on a much grander scale. The Robin Hood Tax campaign led by National Nurses United calling for a Financial Transaction Tax and a rejuvenated grassroots movement for single-payer healthcare will both be necessary to restructure healthcare that will actually begin to work in the interests of patients and healthcare workers. Vermont activists built an impressive campaign to win single-payer in that state, and both New York and California have active legislation in hopes of jumping on the state single-payer bandwagon. In the meantime, local battles over hospital closure can prove fertile ground to highlight the growing scarcity of healthcare access both in urban and rural areas. In New York City, the fight to save LICH and Interfaith became citywide news, when Bill de Blasio got arrested in a planned civil disobedience at LICH and used this issue as a springboard for his successful mayoral bid. Also, states that currently have balked at Medicaid expansion could be important sites for progressive forces to build a movement. The Moral Monday movement in North Carolina points to the potential for such initiatives.

In these upcoming battles, it’s very important that we be crystal clear about what the ACA represents. Massive corporate giveaways of taxpayer money, hundreds of billions in reductions in federal programs, funding restrictions that facilitate the destruction of public healthcare and incentivize hospital closures, layoffs, automation, and deskilling are all trademarks of the neoliberal theory and practice of Obama’s Affordable Care Act. We must fight to reverse this austerity and fight for a healthcare system with full funding, genuine access, and where patients and healthcare workers make decisions in their complimentary best interests.

- Michael McAuliff, “Obamacare Is Socialism: Rep. Louie Gohmert, Steven King Attack,” Huffington Post, March 27, 2012, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/03/27/obamacare-socialism-louie-gohmert-steve-king_n_1383973.html.

- McAuliff 2012.

- Mark Memmott, “Obama: Health Care Is ‘Most Significant’ Legislation Since Medicare,” The two-way: NPR’s News Blog, December 23, 2009, http://www.npr.org/blogs/thetwo-way/2009/12/obama_health_care_npr_intervie.html.

- Paul Krugman, “Hurray for Health Reform,” New York Times, March 18, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/19/opinion/krugman-hurray-for-health-reform.html.

- Phillip Longman and Paul S. Hewitt, “After Obamacare,” Washington Monthly, January/February 2014, http://www.washingtonmonthly.com/magazine/january_february_2014/features/after_obamacare048357.php?page=all.

- World Health Organization, “World Health Statistics 2013”, 2013, http://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/2013/en/.

- World Health Organization, “World Health Report 2000”, 2000, http://www.who.int/whr/2000/en/whr00_en.pdf.

- A.W. Gaffney, “The Neoliberal Turn in American Healthcare,” Jacobin, April 15, 2014, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2014/04/the-neoliberal-turn-in-american-health-care.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “National Healthcare Expenditures 2012 Highlights”, 2012, http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/downloads/highlights.pdf.

- Executive Office of the President, Council of Economic Advisors, “The Economic Case for Health Care Reform,” Whitehouse.gov, June, 2009, http://www.whitehouse.gov/administration/eop/cea/TheEconomicCaseforHealthCareReform.

- David McNally, Global Slump (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2011), 22.

- Roger Bybee, “Crisis = Opportunity for Single-Payer: Fiscal crises force Obama to save costs via a single-player plan,” Dollars & Sense, March 9, 2009, http://dollarsandsense.org/archives/2009/0309bybee.html.

- Adam Davidson, “The President Wants You to Get Rich on Obamacare,” New York Times, October 30, 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/03/magazine/the-president-wants-you-to-get-rich-on-obamacare.html?_r=0.

- Glenn Greenwald, “Obamacare architect leaves White House for pharmaceutical industry job,” The Guardian, December 5, 2012, http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree....

- Richard Cooper, “Inequality Is At The Core of High Health Care Spending: A View From the OECD”, Health Affairs Blog, October 9, 2013, http://healthaffairs.org/blog/2013/10/09/inequality-is-at-the-core-of-high-health-care-spending-a-view-from-the-oecd/.

- Executive Office of the President, Council of Economic Advisors, “The Economic Case for Health Care Reform,” Whitehouse.gov, June, 2009, http://www.whitehouse.gov/administration/eop/cea/TheEconomicCaseforHealthCareReform.

- Charles Idelson, “Bad Medicine”, National Nurse, June, 2013, http://nnumagazine.uberflip.com/i/147208/2.

- Annie Lowrey, “Slowdown in Health Costs’ Rise May Last as Economy Revives,” New York Times, May 6, 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/07/business/slowdown-in-rise-of-health-care-costs-may-persist.html.

- Sarah Kliff, “The 2.8 trillion dollar question: Are healthcare costs growing fast again,” Vox, April 30, 2014, http://www.vox.com/2014/4/15/5612900/health-spending-growth-fast.

- Jonathan Cohn, “Obamacare Deadline: It’s OK to Like the Affordable Care Act Again,” New Republic, 2014, http://www.newrepublic.com/article/117217/obamacare-deadline-its-ok-affordable-care-act-again.

- Kliff 2014.

- “Startup insurers compete on state exchange,” Crain’s Health Pulse, November 11, 2013, http://www.crainsnewyork.com/article/20131111/PULSE/131109892.

- Bruce Jaspen, “Ad Spending on Obamacare May Make Don Draper Blush,” Forbes, May 11, 2013, http://www.forbes.com/sites/brucejapsen/2013/05/11/ad-spending-on-obamacare-may-make-don-draper-blush/.

- Melanie Evans, “Reform Update: ACA will accelerate hospital mergers, Moody’s says,” Modern Healthcare, October 23, 2013, http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20131023/NEWS/310239966.

- Julie Creswell, “New Laws and Rising Costs Create a Surge of Supersizing Hospitals,” New York Times, August 12, 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/13/business/bigger-hospitals-may-lead-to-bigger-bills-for-patients.html.

- Martin Gaynor, and Robert Town, “The Impact of Hospital Consolidation: Update,” The Synthesis Project, The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Policy Brief No. 9, June, 2012, http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/rep....

- Phillip Longman and Paul S. Hewitt, “After Obamacare,” Washington Monthly, January/February 2014, http://www.washingtonmonthly.com/magazine/january_february_2014/features/after_obamacare048357.php?page=all.

- Jim Yanci, Michael Wolford, and Pagie Young, “What Hospital Executives Should Be Considering in Hospital Mergers in Acquisitions,” Dixon Hughes Goodman, LLP, Winter 2013, http://www.dhgllp.com/res_pubs/Hospital-Mergers-and-Acquisitions.pdf.

- Yanci, et. al., 2013.

- Adam Davidson, “The President Wants You to Get Rich on Obamacare,” New York Times, October, 30, 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/03/magazine/the-president-wants-you-to-get-rich-on-obamacare.html?_r=0.

- Davidson 2013.

- Davidson 2013.

- Davidson 2013.

- Nicole Aschoff, “Vultures in E.R.,” Dollars & Sense, January/February 2013, http://dollarsandsense.org/archives/2013/0113toc.html.

- Aschoff 2013.

- Aschoff 2013.

- Aschoff 2013.

- Aschoff 2013.

- Thomas L. Friedman, “Obamacare’s Other Surprise,” New York Times, May 25, 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/26/opinion/sunday/friedman-obamacares-other-surprise.html.

- Matthew Herper, “Obamacare Billionaire: What One Entrepreneur’s Rise Says About The Future of Medicine,” Forbes, April 18, 2012, http://www.forbes.com/sites/matthewherpe....

- Robert Kuttner, “Obama’s Gift to the Republican,” Huffington Post, November 17th, 2013, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/robert-kuttner/obamacare-republicans_b_4293314.html.

- Alex Gourevitch, “Obama’s Anti-Politics and the Affordable Care Act,” Jacobin, December 2, 2013, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2013/12/obama-hoist-by-his-own-petard/.

- Sheryl Gay Stolberg, “Reaping Profit After Assisting on Health Law,” New York Times, September 17th, 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/09/18/us/politics/reaping-profit-after-assisting-on-health-law.html.

- Alan Fram, “Beig Pharma Wins Big With Health Care Reform,” Huffington Post, March 29, 2010, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2010/03/29/big-pharma-wins-big-with_n_516977.html.

- Craig B. Garner, “California’s Vanishing Community Hospital: An Endangered Institution,” California Health Law News, Vol. 29, Issue 4, Fall 2011, http://craiggarner.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/Californias-Vanishing-Hospitals.pdf.

- Sara R. Collins, Bradfod H. Gray, and Jack Hadley, “The For-Profit Conversion of Nonprofit Hospitals in the U.S. Healthcare System: Eight Case Studies,” The Commonwealth Fund, May 2001, http://www.commonwealthfund.org/~/media/files/publications/fund-report/2001/may/the-for-profit-conversion-of-nonprofit-hospitals-in-the-u-s--health-care-system--eight-case-studies/collins_convstudies_455-pdf.pdf.

- D. Douglas Metcalf, “Health Reform’s New Charity Care Requirements for Hospitals: Achieving Compliance to Avoid Penalties,” Becker’s Hospital Review, April 12, 2013, http://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=c53e6f4c-6007-4d12-96fe-f292cfda9b48.

- Nina Bernstein, “Plan to Allow Investment in 2 Hospitals Is Dropped,” New York Times, March 26, 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/27/nyregion/new-york-state-budget-drops-plan-to-allow-for-profit-investment-in-hospitals.html?_r=0.

- Bob Herman, “7 Hospital Bankruptcies and Closures in 2014 Thus Far,” Becker Hospital Review, March 31, 2014, http://www.beckershospitalreview.com/finance/7-hospital-bankruptcies-and-closures-in-2014-thus-far-q1.html.

- D. Douglas Metcalf, “Health Reform’s New Charity Care Requirements for Hospitals: Achieving Compliance to Avoid Penalties,” Becker’s Hospital Review, April 12, 2013, http://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=c53e6f4c-6007-4d12-96fe-f292cfda9b48.

- Mary Agnes Carey, “FAQ: Decoding The $716 Billion in Medicare Reductions,” Kaiser Health News, August 17, 2012, http://www.kaiserhealthnews.org/stories/2012/august/17/faq-716-billion-medicare-reductions.aspx.

- Paul Davidson and Barbara Hansen, “A Job Engine Sputters As Hospitals Cut Staff,” USA Today, October 13, 2013, https://portside.org/2013-10-14/job-engine-sputters-hospitals-cut-staff.

- Mary Agnes Carey, “FAQ: Decoding The $716 Billion in Medicare Reductions,” Kaiser Health News, August 17, 2012, http://www.kaiserhealthnews.org/stories/2012/august/17/faq-716-billion-medicare-reductions.aspx.

- Robert Pear, “Medicare Plan for Payments Irks Hospitals,” New York Times, May 30, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/31/health/policy/31hospital.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0.

- Jordan Rau, “Medicare Discloses Hospitals’ Bonuses, Penalties Based on Quality,” Kaiser Health News, December 20, 2012, http://www.kaiserhealthnews.org/stories/2012/december/21/medicare-hospitals-value-based-purchasing.aspx.

- “Affordable Care Act Update: Implementing Medicare Cost Savings,” Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, http://www.cms.gov/apps/docs/aca-update-implementing-medicare-costs-savings.pdf.

- Robert Pear, “Medicare Plan for Payments Irks Hospitals,” New York Times, May 30, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/31/health/policy/31hospital.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0.

- Robert Pear, “Medicare Plan for Payments Irks Hospitals,” New York Times, May 30, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/31/health/policy/31hospital.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0.

- Dan Goldberg, “House Budget Tweak Costs N.Y. Hospitals Millions,” Capital New York, December 13, 2013, http://www.capitalnewyork.com/article/city-hall/2013/12/8537357/house-budget-tweak-costs-ny-hospitals-millions.

- “Fiscal Survey of States: An Update of State Fiscal Conditions,” The National Governors Association and the National Association of State Budget Officers, Spring, 2012, http://www.nasbo.org/sites/default/files/Spring%202012%20Fiscal%20Survey_1.pdf.

- Phil Galewitz and Matthew Fleming, “13 States Cut Medicaid to Balance Budgets,” Kaiser Health News, July 24, 2012, http://www.kaiserhealthnews.org/Stories/2012/July/25/medicaid-cuts.aspx.

- Sabrina Tavernise, “Cuts in Hospital Subsidies Threaten Safety-Net Care,” New York Times, November 8, 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/09/health/cuts-in-hospital-subsidies-threaten-safety-net-care.html?pagewanted=2&_r=0&emc=eta1.

- Emily P. Walker, “Medicaid to Quit Paying for Preventable Events,” MedPage Today, June 1, 2011, http://www.medpagetoday.com/PublicHealth....

- Nina Bernstein, “Hospitals Fear Cuts in Aid for Care to Illegal Immigrants,” New York Times, July 26, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/27/nyregion/affordable-care-act-reduces-a-fund-for-the-uninsured.html?pagewanted=2.

- Corey Davis, “Q&A: Disproportionate Share Hospital Payments and the Medicaid Expansion,” National Health Law Program, July, 2012, http://www.apha.org/NR/rdonlyres/328D24F3-9C75-4CC5-9494-7F1532EE828A/0/NHELP_DSH_QA_final.pdf.

- Sabrina Tavernise, “Cuts in Hospital Subsidies Threaten Safety-Net Care,” New York Times, November 8, 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/09/health/cuts-in-hospital-subsidies-threaten-safety-net-care.html?pagewanted=2&_r=0&emc=eta1.

- Abby Goodnough, “Hospitals Look to Health Law, Cuttin Charity,” New York Times, May 25, 2014, http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/26/us/hospitals-look-to-health-law-cutting-charity.html?emc=eta1&_r=0.

- Marsha Mercer, “Hospital Mergers May Be Good for Business, But Patients Don’t Always Benefit,” AARP Bulletin, June, 2013, http://www.aarp.org/health/medicare-insurance/info-06-2013/hospital-mergers.1.html.

- Kelsey Ryan, “Designation change could cut critical access hospital funds,” Wichita Eagle, February 22, 2014, http://www.kansas.com/2014/02/23/3306169/designation-change-could-cut-critical.html.

- Joe Carlson, “OIG Proposal Threatens Enhanced Payments To Two-Thirds Of Critical-Access Hospitals,” Modern Healthcare, August 15, 2013, http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20130815/NEWS/308159958/oig-proposal-threatens-enhanced-payments-to-two-thirds-of-critical.

- Zack Budryk, “Hospital closures will leave ‘medical deserts’,” Fierce Healthcare, November 11, 2013, http://www.fiercehealthcare.com/story/hospital-closures-will-leave-medical-deserts/2013-11-11.