Defending our right to criticize Israel

Uncivil Rights:

The repression of the Palestine solidarity movement is intensifying. Governmental bodies in Western Europe, the United States, and Canada have passed laws that criminalize the boycott of Israeli occupation and apartheid, running roughshod over the democratic freedoms these societies claim to uphold. This June, Governor Andrew Cuomo of New York provided one of the most alarming examples of this pattern of state repression when he signed an executive order banning state contracts with BDS supporters and creating a blacklist of pro-Palestinian dissidents.

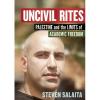

Activists preparing to confront this new reality will find a treasure trove of insights and polemics in Steven Salaita’s recent book, Uncivil Rites: Palestine and the Limits of Academic Freedom, which documents the author’s experience of repression in a gripping collection of vignettes, manifestos, testimonies, and other commentaries.

In October 2013, Salaita, an activist and scholar who writes about colonialism and racism, with a focus on Palestinian, Arab, and Native American histories, accepted a position as associate professor with indefinite

tenure from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC). The summer before his first semester at UIUC, over the course of fifty-one days, Israel’s military assault on Gaza killed over 2,100 Palestinians, including 551 children, and displaced 475,000 more, reducing much of the densely populated area to ruins. Salaita responded on Twitter to the massacre, calling for an end to the bombardment and the occupation of the West Bank.

Appalled by his comments, some UIUC Board of Trustees members intervened and proceeded to overturn Salaita’s appointment. In the months that followed, Salaita and thousands of supporters around the country launched an inspiring campaign to hold UIUC accountable, which helped broaden Palestine solidarity movement.

A year after the UIUC’s maneuver, the university agreed to settle the case. He later accepted a position as the Edward Said Chair of American Studies at the American University of Beirut. The deal fell short of securing Salaita’s demand that the university reinstate him.

UIUC cynically attempted to justify its dismissal of Salaita on the grounds that his tweets were anti-Semitic and put Jewish students at risk. Out of the thousands of tweets posted by Salaita, which focused on equality and liberation in Palestine, the UIUC administration’s social media monitors fixated on only a couple to stoke panic:

July 19, 2014: If it’s “anti-Semitic” to deplore colonization, land theft, and child murder, then what choice does any person of conscience have? #Gaza

June 19, 2014: You may be too refined to say it, but I’m not: I wish all the fucking West Bank settlers would go missing.

The first tweet is clearly a commentary on the abuse of the concept of anti-Semitism by Israel to distract from its crimes, not an incitement to anti-Jewish hatred. The second drew the most ire because it referred to the abduction of three Israeli settlers in the West Bank, who were found murdered and buried outside Hebron eleven days after Salaita’s remarks. He is an adherent of the nonviolent boycott, divestment, and sanctions (BDS) movement, and obviously did not intend to call for the mass abduction of Jewish settlers with these tweets. Instead, he was giving expression to the indignation of 3.5 million Palestinians in the West Bank at the colonization and military occupation of their homeland.

That Salaita believes in winning universal freedom peacefully and not through ethnic or race wars appears obvious to anyone scrolling through his Twitter feed. The two tweets quoted above were published side-by-side with the following statements taken from the same period:

July 17, 2014: I absolutely have empathy for Israeli civilians who are harmed. Because I am capable of empathy, I deeply oppose colonization and ethnocracy.

July 18, 2014: It’s a beautiful thing to see our Jewish brothers and sisters around the world deploring #Israel’s brutality in #Gaza.

July 19, 2014: My stand is fundamentally one of acknowledging and countering the horror of anti-Semitism.

July 23, 2014: #ISupportGaza because I believe that Jewish and Arab children are equal in the eyes of God.

July 27, 2014: I refuse to conceptualize #Israel/#Palestine as Jewish-Arab acrimony. I am in solidarity with many Jews and in disagreement with many Arabs.

UIUC claims it fired Salaita to keep its students safe, but the administration has faced criticism for its lack of concerns for students’ safety in the past, and done little. A 2014 study revealed that a third of students of color at UIUC had been verbally or physically assaulted on campus, 60 percent indicated that they had experienced forms of racism during their time at school, and 80 percent claimed UIUC was in effect a segregated institution.

This systematic racism on campus is reinforced by the presence of racist faculty members, like UIUC political science professor Robert Weissberg, who is a frequent speaker at conferences of the openly white-supremacist magazine, American Renaissance. To make matters worse, until 2007 UIUC kept a racist caricature of a Native American as the school’s mascot. Unlike Salaita’s tweets, these things constitute actual bigotry and violence at the university, and yet the administration has done very little to resolve or even address them.

Salaita’s book exposes these hypocrisies to make a far-reaching critique of the contemporary university system: the academy’s real purpose, despite much high-minded rhetoric about enlightenment and liberty, is to prepare new generations to maintain the unequal and unjust social order in which we live. The university always attempts to place increasing power in the hands of administrators and functionaries in order to more efficiently direct academic programming to suit capitalism’s needs, allowing bureaucratic bosses of the kind who laid off Salaita to control campus life. Salaita argues that this top-down structure of administrative dominance is incompatible with freedom of speech and expression, which requires that every individual be free to speak their mind without fear of punishment.

Beyond the campus walls, Salaita has a lot to say about the battle of ideas in the Palestinian struggle. Throughout this ordeal, the UIUC administration lashed out against him for lacking “civility,” pointing to his animated, angry tone on social media. Such attempts to smear advocates of Palestinian rights as uncivil are meant to distract from the everyday reality of violence and oppression which continues in Palestine, where 1.8 million people languish under the decade-long blockade of Gaza, more than two million face a military occupation in the West Bank, 1.4 million live as second-class citizens in Israel proper, and over five million Palestinians live in exile, barred from returning to their ancestral homeland.

Discussions about Palestine have to be persistently brought back to this fundamental reality. If being “civil” requires accepting the status quo for Palestinians, then civility isn’t worth defending. Besides, what matters most isn’t how polite or proper we are when we speak, but what we actually believe in and do. “Many genocides have been glorified (or planned) around dinner tables adorned with forks and knives made from actual silver, without a single inappropriate speech act having occurred,” Salaita explains.

At the same time, Salaita’s book offers subtle reflections on the Palestinian struggle. Among these commentaries are his reflections on the question of anti-Semitism. The author recognizes that the Zionist conquest of Palestine is unlike many other instances of colonization in that much of the settler population was motivated by a desire to escape racist persecution and genocide in Europe. Zionism is a colonial project that predates the Holocaust by a half century, and was unlikely to have become a mass movement without the horrors of the 1930s and 1940s.

The task of ending anti-Semitism, argues Salaita, requires that we fight to eradicate all forms of inequality and oppression. The subjugation of another people by creating an exclusive, ethnocentric state only perpetuates the horrors of racism. Salaita goes on to argue that it’s not the Palestinians who have a problem living side by side with Jews, but vice versa:

I want to make something clear: I hate anti-Semitism. “Hate” is a strong word, which is precisely why I use it. As I’ve said many times before, I would like to share both a nation and a national identity with my Jewish brothers and sisters. No Zionist I know shares that sentiment.

This vision of a single state in greater Israel-Palestine, with full and equal rights for all regardless of ethnicity, is central to the BDS movement and worthy of our active support.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Google+

Google+ Tumblr

Tumblr Digg

Digg Reddit

Reddit StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon