Legacies of colonialism in Africa

“The Conference of Berlin was able to carve up a mutilated Africa among three or four European flags. Currently the issue is not whether an African region is under French or Belgian sovereignty but whether the economic zones are safeguarded. Artillery shelling and scorched earth policy have been replaced by an economic dependency.” —Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth1

“The Bretton Woods institutions are like arsonists, lighting new social fires, then waiting for the NGOs and local communities to play firefighter.” —Eric Toussaint, Your Money or Your Life: The Tyranny of lobal Finance2

President Barack Obama made his first visit to sub-Saharan Africa as president in July, 2009, speaking in Accra, Ghana. Despite a decades-long trail of broken promises to Africa on aid and development, Obama’s speech in Accra was marked by finger-wagging and reprimands, and an insistence that African nations’ own “mismanagement” and “lack of democracy” are to blame for their economic and social problems. Obama told the Ghanaian parliament,

Yes, a colonial map that made little sense bred conflict, and the West has often approached Africa as a patron, rather than a partner. But the West is not responsible for the destruction of the Zimbabwean economy over the last decade, or wars in which children are enlisted as combatants. . . . No person wants to live in a society where the rule of law gives way to the rule of brutality and bribery. That is not democracy; that is tyranny, and now is the time for it to end.3

Obama’s speech was made at the height of the 2008–2009 global recession. Yet lest we imagine that this approach was somehow exceptional, we can note the echoes of Obama’s words in an address given by International Monetary Fund (IMF) head Christine Lagarde in Nigeria in early 2016. There she likewise chastised the Nigerian government on fiscal policy and corruption in the face of a major commodity price collapse, admonishing them that “hard decisions will need to be taken on revenue, expenditure, debt, and investment,” and prescribing a stern dose of “resolve, resilience, and restraint.”4

Tough-love talk of “responsibility” aside, then and now, US policy makers actually view economic crisis as an opportunity to rebuild the global economy at the expense of ordinary Africans. In 2008, then-Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner tripled the IMF’s resources from their current level of about $250 billion, with $100 billion coming from the United States. Yet while the IMF directed industrialized nations to enact stimulus plans and bank bailouts, Africa and other Third World regions were compelled to accept spending cuts and other harsh conditions for loans. In fact, said the Jubilee USA Network at the height of the 2008–2009 global recession, “There is a significant danger that the new borrowing that has resulted from a lack of sufficient international grant support . . . will force low income countries to prioritize debt repayment over essential social services and lead to renewed debt crises throughout the developing world.”5

Similarly, today’s economic crisis for “emerging nations” will provide an opportunity for the reimposition of Western fiscal priorities, what anti-Third World debt activist Eric Toussaint has described as “the tyranny of global finance.” As the business presses were reporting in early 2016, a new round of indebtedness and austerity is now unfolding for African economies.6 Likewise, as during the last crisis, ordinary Africans will be compelled to accept punishing conditions handed down by the global financial institutions.

Obama’s comments turn the reality of African poverty and its root causes on their head. Decades of IMF and World Bank (often referred to as the “Bretton Woods institutions” for their creation at the Bretton Woods conference in New Hampshire at the close of World War II) loans and structural adjustment policies have placed an economic stranglehold on African and other Third World nations. “The massive strength of US capital, with more than 50 percent of world manufacturing and finance at its disposal, was used to create the World Bank, the IMF, Marshall Aid and so on.”7 Using the IMF/World Bank as a battering ram, neoliberal policy of trade liberalization forced its way across Africa and the rest of the globe, leaving in its wake decimated social programs, a debt crisis, and low wages—that is, conditions favorable for US investment. The last few decades of neoliberal policy have spelled disaster for the vast majority of ordinary Africans. Each Ghanaian, for example, owes approximately $350 to international financial institutions.8 Countless other examples of poverty and inequality could be given.

The comments from Obama and Lagarde illustrate two general kinds of explanations in the mainstream media and official circles about the causes of poverty in Africa, neither of which are mutually exclusive: one is a scolding approach where Western politicians, officials, and investors chide African governments on economic policy, with stern paternalism combined with hand-wringing concern. Admonitions from the West transform into narratives of Africa as an eternal basket case using blatantly hypocritical blame-the-victim rhetoric. One version emerges from some development and global advocacy circles that claim an antipoverty agenda but that also share key assumptions with their Bretton Woods and development bank partners: that the success of any development policy in Africa depends on Western intervention. These shared assumptions include a conviction in the inability of African governments and ordinary people to independently run their own societies. As a case in point, Bono’s ONE Campaign issued a strong finger-wagging about the need for African governments to act more responsibly, warning that the “New global development agenda has little hope of succeeding unless those same governments—together with private-sector partners and many others—also agree on an effective strategy to finance it.”9

However, this version is a vastly distorted account that elides or erases the destructive role played by foreign multinational corporations. As Clark Gascoigne of Global Financial Integrity comments, “In development circles we talk a lot about how much aid is going to Africa, and there’s this feeling among some in the West that after we’ve been giving this money for decades, it’s Africa’s fault if the continent’s countries still haven’t developed.”10

The other narrative is newer, found in the business presses beginning around the early to mid-2000s, championing—with scarcely contained excitement—a new surge in investment on the continent. Certainly Africa has undergone a recent boom for global corporations, asset managers, and the like, with vast returns on commodities that enabled African growth rates to bounce back faster than many other parts of the globe after the recession in 2008–2009. In recent years, investment in other industrial sectors has also taken off, with booms in communications, technology, and the service sector. Accompanying this growth has been the excited declaration of a new African middle class and a “diversified” economy, ready to weather any global downturn in prices. Needless to say, this narrative has already been seriously punctured by the commodities price crash of the last few years.

In fact, shocking levels of inequality, oppression, and poverty are no less prevalent today than they have been since the end of colonialism. Patrick Bond, for one, has argued that Africans are poorer today than they were at independence.11 Today, however, even sharper unevenness exists not only between Africa and the West, but also within African nations themselves. While the dramatic narrative of “Africa rising” in the first decades of the new millennium champions the “boom” in investment and growth, poverty and underdevelopment remain dire. Crippling poverty has meant, for example, a health care crisis that has reached epidemic proportions on a continent where, according to the World Health Organization, the average life expectancy at birth is only fifty-eight years; ten times as many people on the continent will die of HIV/AIDS than in Europe; and Africa has one-tenth the rate of physicians per population as compared to Europe and the United States.12 One billion people worldwide have no access to any form of sanitation facilities;13 695 million of those without access live in sub-Saharan Africa.14

Postcolonial economic development on the continent has also resulted in combined and uneven development that has concentrated industrial growth in key centers such as Nigeria and South Africa and left other regions far behind. According to the World Bank, those two countries together have accounted for 55 percent of the industrial value in sub-Saharan Africa, while the other fifty-two countries share the remainder.15 Africa’s manufacturing exports nearly tripled from $72 billion in 2002 to $189 billion in 2012, but a mere four countries—Egypt, Morocco, South Africa, and Tunisia—accounted for a full two-thirds of these exports.16 Class polarization has expressed itself most sharply in these centers, with enthusiastic ruling-class support for market-based neoliberal reform on the one hand, and higher levels of working-class resistance on the other.

In fact, within those centers, the class contradictions are profound. In South Africa, more than 40 percent of the population languishes in extreme poverty while the top quarter of the population earns 85 percent of the country’s wealth.61 In Nigeria, 80 percent of the nation’s oil wealth is concentrated in the hands of 1 percent of the population.62 As John Ghazvinian describes in Untapped: The Scramble for Africa’s Oil,

Foreign oil companies have conducted some of the world’s most sophisticated exploration and production operations . . . but the people of the Niger Delta have seen none of the benefits. While successive military regimes have used oil proceeds to buy mansions in Mayfair or build castles in the sand in the faraway capital of Abuja [Nigeria], many in the Delta live as their ancestors would have done hundreds, even thousands of years ago.17

The surge in commodity prices and foreign investment has replicated this inequality in other sites on the continent. For example, “The boom in exports all too frequently benefited only a tiny stratum. One of the most extreme cases was Angola, a major producer of oil and diamonds. In Luanda, where in 1993 a staggering 84 percent of the population was jobless or underemployed, inequality between the highest and lowest income deciles ‘increased from a factor of 10 to a factor of 37 between 1995 and 1998 alone.’”18 This dynamic has been multiplied many times over across Africa.

Origins of African poverty

The forces underlying African poverty are far from reducible to problems of “corruption” and “governance,” but rather are rooted in historic relationships of exploitation within a larger capitalist system, where political and economic strategies on the part of the West came to the fore and were advanced at key moments. This period will be sketched out here: broadly speaking, the thwarting of industrial development in conditions created under colonialism, the national development models attempted by African ruling classes after independence, and the narrowing of those horizons into single-commodity export economies and IMF/World Bank--imposed austerity, have all combined to produce debt crises, collapses of infrastructure, poverty, lack of access to health care, high rates of HIV/AIDS, low wages, low literacy rates, an explosion of urban slums, and a host of other poor grades on human development indicators.

Deep inequality, oppression, and misery persist despite the African boom. The dominant narrative on African poverty reduces essentially to this question: Why hasn’t a rising tide lifted all boats? A raft of explanations, many of them ahistorical, continue to grapple with these questions, from the academic “economic development” literature to the pages of the Financial Times, many of which conclude that intrinsic characteristics of African societies and economies are at fault. Economist Paul Collier is one influential proponent of what amounts to a static account focused on ostensible weaknesses of governance and lack of accountability (i.e., corruption), an essentially ahistorical approach to arguably deeper structural questions of political economy.19

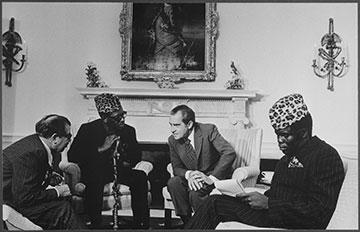

Charlie Kimber has pointed out that the dogma on good governance has its own historicity. Particularly during the Cold War, the West actively sought alliances with African elites, sometimes with horrific records on authoritarianism, corruption, and brutality, looking away from this track record when expedient. Zaire’s Joseph Mobutu, who managed to accumulate vast sums in the course of his rule, was a case in point. Later, however, with the neoliberal concern about breaking through obstacles to privatization, Western opposition to strong state regulation was increasingly reframed as a focus on political and government “reform,” stressing the urgency for favorable investment climates. As Kimber describes, the moment was one of “corruption regarded as rooted in the state itself and therefore the ‘war against corruption’ could usefully be emblazoned on the banners of the privatizers and the pro-market militias. Today governance-related conditionalities are central to aid packages.”20

How state power and its institutions are characterized is of course a political question. Imperial powers have wielded the hammer of governance as a weapon to ensure the subservience of oppressed nations and as a tool to maintain a competitive advantage against their rivals. On the other hand, these strictures can easily be brushed under the rug when expedient. Apartheid South Africa—like Mobutu’s Zaire—well exemplifies the hypocrisy of the selective critiques of the West:

On average as much as 7 percent of GDP per annum left South Africa as capital flight between 1970 and 1988, an equivalent of 25 percent of non-gold imports. This was entirely due to the transfer activities of the major corporations like Anglo-American and the Rembrandt Group. And their behavior was no less illicit than that of the dictators. Shifting private funds out of South Africa in the 1980s not only defied local capital controls, but also broke the international sanctions regime on apartheid. As such, the neo-liberal pathologizing of the corrupt black African state simply does not hold. The private ‘white’ capitalists of South Africa were busy engaging in capital flight as well.21

The Left has reached a very different set of conclusions for understanding inequality in Africa today, deriving from a range of frameworks—the dependency theories of Andre Gunder Frank and Samir Amin; Walter Rodney’s underdevelopment thesis; the accumulation by dispossession theories of David Harvey, Patrick Bond, and others; and the classical Marxist approach. Yet the common thread connecting these varied approaches is a shared assumption of the detrimental legacies of colonialism and neoliberalism: essentially, that imperial powers and global financial institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank are to blame for both the historic and contemporary inequality on the planet. African poverty is not simply a fact of nature but was manufactured through the historical processes of exploitation and neoliberalism, built upon and impacted by the legacies of colonialism and underdevelopment. Writers such as Eric Toussaint, among many others, have made critical contributions to an understanding that Western foreign policy toward Africa does not merely produce poverty and inequality as an accidental byproduct, but rather, that Third World debt, structural adjustment, privatization, and trade liberalization are intentional strategies of a neoliberal agenda.

Marxists have situated the neoliberal era in the context of a crisis not just of profitability in the post-1970s recession period, but also more broadly as a political and economic program to manage the contradictions of the system of capitalism: the competitive drive to continuously secure access to markets, investment opportunities, and resources. For David Harvey, among others, the neoliberal era is the period of the post-1970s crisis to the present, marked by a host of economic policies aimed at breaking down barriers to trade and investment by the West and to facilitate the political and social conditions most favorable for capital accumulation. Conditions such as compliant local regimes, low wages, weak (or no) unions, overall high levels of labor exploitation, weak regulatory environments (i.e., legal and environmental safeguards protecting the interests of the host country), and so on.

In the period of postindependence Africa, Western governments and institutions—through the particular structure of investment, aid, loans, and trade policy—extended relationships whose nature was fundamentally similar to the prior era. In other words, within the newly-emerged rubric of independence, the West aimed to impose economic and political policies that largely continued—rather than overturned—structural conditions of weak states, political instability, and a lopsided structural pattern of their economies inherited from colonialism. Within the historical trajectory of the previous half-century, various strategies can be identified, emerging at particular moments: Western investment and development of the 1950s and 1960s, so as to facilitate extraction and accumulation while balancing the new political realities of independent states; to the devastation of structural adjustment, Third World debt and neoliberal diktat of the 1970s–1990s; to the explosion in private investment and the “favorable business environment” of today.

This article will trace these historical developments in African political economy, sketching out the origins of today’s conditions to the legacies of weak colonial states, lopsided economies, and the assault of structural adjustment programs (SAPs) that paved the way for the neoliberal boom and the past decade’s investment surge. Yet, as will be outlined below, this rosy business environment is fraught with its own contradictions: intensified local and regional competition, and markedly heightened imperial competition between the US and China. Last—and by no means least—competitive pressures and a downturn in the Chinese economy have recently given way to a new round of crises, one that threatens to drag down other sections of the globe along with it. The classic boom and bust cycle of capitalism—and the possible retreat of the new horde of enthusiastic corporate investors—present a serious threat to working class and poor Africans, one likely to deepen the misery for many on the continent.

Legacies of colonialism: Weak states and economic underdevelopment

The weakness of postcolonial nations was a result of colonialism—which left a political heritage of weak states with limited control over territory and regimes that relied on ethnic divisions, a centralized authority, and patronage systems inherited from colonial rule. Resting on a weak political base, new national leaders were thus vulnerable to the pull of internal influence and corruption, and the support of external imperial patrons, all contributing to conditions where the United States (or in some cases, the USSR) found an opening to replace the influence of these countries’ former colonial masters. Both sides weighed strategic considerations and influence in various African countries that had become contested states in early Cold War competition, such as Guinea and Mali.

Under colonialism, the major powers on the continent set up administrative apparatuses that in some cases—mainly the British and the Germans—utilized local rulers, but, as Rodney writes, in no instance would the colonizers accept African self-rule. The French, on the other hand, virtually destroyed all indigenous political systems and established their own networks of administrators. Infrastructure such as roads were built not only to facilitate the movement of commodities and machinery, but also that of the colonial armies and police required to discipline the indigenous population, whether the expulsion of people from their land or the forced cultivation of cash crops.

African national movements were relatively late-forming in the colonial era and assumed power with a relatively newly created state apparatus and a weak national identity that, in practice, tended to rely upon pitting ethnic groups against each other to mobilize power. Thus, as Peter Dwyer and Leo Zeilig describe in their book on African social movements, “Colonialism had in most cases severely hampered the growth of an indigenous bourgeoisie.”22 This had not always been the case under colonialism, but rather was the product, in the second half of the nineteenth century, of a shift away from the use of educated Africans in colonial administration toward colonially created “native” authorities. Producing these “tribal” leaders allowed European colonial powers to rely on a section of African society for administrative, military, and political roles.

But by the turn of the century, fierce imperial competition drove an expansionist push in Africa, deepening conflict between European and local populations as they tightened their overall control over the colonies altogether. Under these intensified conditions, alliances with local “partners” were increasingly unsustainable, and African leadership was increasingly excluded from the state.23 These colonial processes undermined the development of a native bourgeoisie and likewise left a political imprint in the postcolonial era, when new ruling classes were attempting to establish some degree of political and economic independence, despite the overhang of these legacies. Dwyer and Zeilig show that in the case of the Congo, for example, with “the economy already cornered by foreign corporations . . . all that [aspiring African elites] could sell was their political power and influence in the state machinery.”24 These historical developments formed the material basis for new regimes vulnerable to the pull of patronage or “clientelism,” as Ugandan scholar Mahmood Mamdani has called it.25

For some new rulers, adhering to the “colonial mold of the state” was a logical objective, cemented by nationalist leaders who fought to secure sovereignty for small states.26 For those states emerging from colonialism, new ruling classes were mainly drawn from the urban middle classes, with little accountability to weak indigenous landowners or capitalists,27 able to remain relatively autonomous vis-à-vis local capital (while remaining under the rule of foreign investors and powers).28 Frantz Fanon describes in The Wretched of the Earth how these new rulers draped themselves in the nationalism and aspirations of the anticolonial revolutions so as to facilitate accumulation in which they would also be beneficiaries:

Spoiled children of yesterday’s colonialism and today’s governing powers, they oversee the looting of the few national resources. Ruthless in their scheming and legal pilfering they use the poverty, now nationwide, to work their way to the top through import-export holdings, limited companies, playing the stock market, and nepotism. They insist on the doctrine of nationalization for business transactions, i.e., reserving contracts and business deals for nationals. Their doctrine is to proclaim the absolute need for nationalizing the theft of the nation.29

Governmental and legal structures bore the marks of the colonial era, an imprint extended to the present day in some cases. “Tribalism” intersected with political rule in the postcolonial period such that district and local-level leaders continued on in appointed (unelected) roles, accountable only to the newly formed central governments. Countries such as Kenya—the site of large-scale colonial land seizures—maintained the legal basis for such practices, keeping laws on the books that enshrined communal land as “government property.”30 Legal loopholes established in the colonial era continue to be used today to sanction the open theft of commonly held land by foreign multinationals, in an agricultural land grab that has seized millions of hectares for corporate investment.31

The ideological visions for these new states were not one-dimensional. A political divide within the nationalist currents expressed competing frameworks at the top among those new layers of leaders who explicitly embraced coordination and collaboration with the West for the coming era, and those leaders advocating and championing independence, “Africanization,” regional unity, and a left-wing framing of state-directed national development. The radical wing of the nationalist movements also tended to draw upon a base of trade unions, migrant workers, and students.32 While himself an influential figure under the mantle of “African socialism,” Ghanaian president Nkrumah also wrote of the tensions between these two poles, and the class implications of this model. Later his class background would prove decisive, and Ghana emblematic of the failure of those left-wing aspirations, the “end of an illusion,” as Bob Fitch and Mary Oppenheimer would describe it: “Nkrumah was the perfect representative of the Gold Coast petty bourgeoisie. With admirable clarity he defined his position as one which opposed ‘particular consequences’ but accepted the assumptions of the political system.”33 However, Nkrumah correctly identified the dynamics in 1963:

In the dynamics of national revolution there are usually two local elements: the moderates of the professional and “aristocratic” class and the so-called extremists of the mass movement. . . . The moderates are prepared to leave the main areas of sovereignty to the colonial power, in return for a promise of economic aid. The so-called extremists are men who do not necessarily believe in violence but who demand immediate self-government and complete independence. They are men who are concerned with the interests of their people and who know that those interests can be served only by their own local leaders and not by the colonial power.34

These divergent views—left and right—both reflected variants on rule “from above,” a new, postcolonial order that nonetheless retained the class divisions of a society resting on accumulation and competition, along state capitalist lines. As Mamdani has described it, in “conservative African states, the hierarchy of the local state apparatus, from chiefs to headmen, continued after independence. In the radical African states . . . [t]he antidote to a decentralized despotism turned out to be a centralized despotism.”35

Rodney recognizes the disproportionate weight and importance of the small African working class as a more stable base of resistance.36 However, “Capitalism in the form of colonialism failed to perform in Africa the tasks which it had performed in Europe in changing social relations and liberating the forces of production.”37

According to Rodney, the working class was too small and too weak to play a liberatory role in the postcolonial period. Albeit reluctantly, he identifies the intelligentsia for that role: “Altogether, the educated played a role in African independence struggles far out of proportion to their numbers, because they took it upon themselves and were called upon to articulate the interests of all Africans. They were also required to . . . focus on the main contradiction, which was between the colony and the metropole. . . . The contradiction between the educated and the colonialists was not the most profound. . . . However, while the differences lasted between the colonizers and the African educated, they were decisive.”38

This leadership was fraught with problems, according to Rodney, but in his view, this balance of class forces was only temporary, and part of the process of becoming a mass revolutionary movement. In his view, “Most African leaders of the intelligentsia . . . were frankly capitalist, and shared fully the ideology of their bourgeois masters. . . . As far as the mass of peasants and workers were concerned, the removal of overt foreign rule actually cleared the way toward a more fundamental appreciation of exploitation and imperialism.”39 Despite Rodney’s somewhat stageist description here of class formation in the postcolonial era, he identified an important characteristic, namely the weak political base of these new nations, hobbled from the beginning by the inherited weaknesses of the prior period.

Lopsided economies

The legacy of the plunder and colonization has been the expansion of capitalism as system and the massive accumulation of capitalists—and “their” nation-states—at the expense of greatly weakened states and economies in Africa. “The wealth that was created by African labor and from African resources was grabbed by the capitalist countries of Europe,” writes Rodney, “Restrictions were placed upon African capacity to make the maximum use of its economic potential. . . . African economies are integrated into the very structure of the developed capitalist economies; and they integrated in a manner that is unfavorable to Africa and insures that Africa is dependent on the big capitalist countries.”40

When colonialism ended, the weak economic and political footing of new African states left them vulnerable to interference from the West. Several aspects of economic development under colonialism produced highly distorted and fragile economies; resulting in economic systems anchored to a narrow export base with a concomitant weak industrial sector and anemic rates of growth. These states inherited an underdeveloped infrastructure geared toward exports, lacking capital, and skewed toward supplying unfinished goods to the advanced countries. In essence, “The development effort of late colonial regimes never did provide the basis for a strong national economy; economies remained externally oriented and the state’s economic power remained concentrated at the gate between inside and outside.”41 These conditions posed severe challenges to the prospects for building sustainable economies capable of protecting nascent industries from the turmoil of global markets. As British socialist Chris Harman has pointed out, “Success in trade in the modern world is only possible if you already have a high level of investment in modern technologies. Countries which do not have that are doomed even when no barriers exist to their selling goods in advanced countries.” Overcoming these historic disadvantages would prove to be immensely difficult.42

Rodney has argued that production proceeded on a different path than in Europe, where the destruction of agrarian and craft economies increased productive capacity through the development of factories and a mass working class. In Africa, he argues, that process was distorted: as in Europe, local craft industry was destroyed, yet industry was not developed outside of agriculture and extraction, and workers were restricted to the lowest-paid, most unskilled work.43

In 1967, a full 90 percent of Africa’s exports were comprised of raw materials such as oil, copper, cotton, coffee, and cocoa.44 For the century up to the late 1960s, the per capita annual rate of growth was less than one percent.45 The growth rate can be contrasted with the United Nations’ goal of a 3 percent growth rate for the 1960s as the “Decade of Development,” launched by President Kennedy at the UN on the heels of his inaugural address where he had declared: “To those peoples in the huts and villages of half the globe struggling to break the bonds of mass misery, we pledge our best efforts to help them help themselves.”46

The growth of cash crops reached such an extreme during the decades of colonialism that food had to be imported, while industrial development was thwarted in Africa itself because manufacturing and the processing of raw materials happened exclusively overseas. Africans were discriminated against in most areas of economic life and wages kept very low, and the profits from the exploitation of African laborers went directly to European bankers and trading companies.

Economic development under colonialism was highly uneven, especially under British colonialism, which created concentrations of workers in key locations, such as mines of central Africa and at the port of Mombassa in Kenya. While this result was an unavoidable outcome of the orientation on extractive industries and its associated transportation infrastructure, these needs were necessarily balanced against colonial concerns of too much industrialization potentially producing “disruptive proletarianization,”47 i.e., class struggle and resistance. These fears were by no means unfounded: working class and peasant struggles were a central feature of the colonial period, and this resistance—among unionized and nonunionized workers, students and agricultural laborers—formed the basis of the mass anticolonial struggles.

Alongside this unevenness, colonial policy produced some institutional uniformity in methods of extracting capital from the continent. British colonial monopolies in the form of marketing boards not only reinforced the tendency toward single commodity production for export by controlling most of the value of exports. These monopolies also amounted to loans in hard currency on the part of the colonies to Britain in the form of the difference between producer and market prices. This dynamic provides context to the resistance of the British Empire to the decolonization process as these boards provided access to the currencies that enabled the import of capital to Britain itself and thus its industrial recovery in the wake of World War II.48 As Fitch and Oppenheimer, for example, describe in their important account on the heels of the overthrow of Nkrumah’s government, the institutional legacy of these colonial marketing boards, as well as the total refusal of banks to provide local credit,49 were decisive in the outflow of capital from Ghana and the “stunting” of the indigenous capitalist class.50

As at least one study of French colonialism in Africa has shown, Africans themselves—and not the colonizers—far disproportionately carried the weight of colonial expenses through taxation.51 The same study demonstrated that very minimal funds were devoted to “productive sectors,” mainly agriculture, which could have provided the basis for economic diversity. Meanwhile, “colonial investments focused on infrastructure supporting export/import transportation rather than focusing on transforming and improving local productive capacity.”52

Civil society

At the time of independence, staggering human and social needs confronted new nations. Contrary to colonial propaganda, where colonizers claimed an investment in the “well-being” of the colonized, the vast bulk of funds spent went towards the military or the colonial administration. Colonial policy actively suppressed education for the majority. Technical education was introduced only in rare instances. For example, the Congo had only sixteen secondary school graduates at the time of independence, out of a total population of thirteen million.53 Likewise, not one doctor was trained in Mozambique during 500 years of Portuguese colonialism.54 Across the continent as a whole, only 1 percent of those in school reached the secondary school level. In 1960, there were only fifty university graduates per year, when “it is calculated that 10 times the number are needed annually—half of them for government service.”55 All told, colonialism left a wake of destruction across the continent: life expectancy plummeted, ecological devastation spread across rural areas that suffered from minimal social services. As Rodney so succinctly puts it, “Colonialism had only one hand—it was a one-armed bandit.”56

Democratic institutions were similarly very weak. Mamdani describes how colonial political systems actively cultivated accumulations of power in some sites over others, based on the particular political interests and alliances at a given moment. In Nigeria, for example, pre-independence electoral reforms were introduced but applied selectively across the country, generating the seeds of inequality whose reverberations would be felt in the decades to come.57

Imperial objectives in the Cold War era

In this context, what were the imperial aims of the US with regards to Africa in the new era? With the approach of the era of independence after World War II, the US saw the emerging period as an opportunity to cement political and economic ties with the new nations of the continent: to forge alliances so as to curb the influence of their competitors, namely the USSR, but also other Western European powers, and to remake the economic order so as to best facilitate accumulation for US capital. For the United States, but also for the USSR, the end of colonialism opened a door for the rising imperial powers to forge their own relations with the new African nations, free from the domination of the European colonial system, a system that had in fact received overall US support at the time.

During the Cold War, superpower competition drove both the US and the USSR to create allies and proxies in Africa as a way to extend their global reach and to overcome the historical advantage of colonial powers’ exclusive domination there. As Sidney Lens has pointed out, the postwar military superiority of the United States provided the opportunity for it to maintain a position from which to subordinate its rivals. The Cold War became an expression of this global aspiration: the United States challenge to the geopolitical power of the USSR and the large areas of the world within its orbit.58 Africa of course was by no means an exception within this global dynamic. As Frantz Fanon has described, “Every peasant revolt, every insurrection in the Third World fits into the framework of the cold war. . . . The full-scale campaign under way leads the other bloc to gauge the flaws in its sphere of influence.”59

For the United States, competition with the USSR drove an ever-shifting network of Cold War alliances in Africa, expressed through a host of tactics, from military funding, proxy and clandestine operations, to the use of the CIA. Military strategy aimed at containment or rollback of the Soviet sphere of influence on the continent entailed undermining African nationalist regimes perceived as in danger of aligning with the USSR or charting a path independent of the West, and its concomitant threat to stability — that is, a climate conducive to investment and capital accumulation. Ghana was a case in point, where Africa’s first leader of the postcolonial era, pan-Africanist president Kwame Nkrumah, was removed in a coup in 1966, revealed later to have been orchestrated by the CIA. As one US national security advisor commented at the time, “Nkrumah was doing more to undermine our interests than any other black African.”60 Despite the willingness of the Nkrumah regime to collaborate with foreign investors, from the US vantage point Ghana’s example in charting the anticolonial path posed an ideological threat to US aspirations on the continent, in a context where “the turning of the Ghanaian capital Accra into a staging point for the African anti-colonial movement started almost immediately after independence and the lessons of the Ghana experience were pressed home.”61

Militarism was inextricable from the political and economic aims of the day. Military bases were used as political leverage, and the basis for outright intervention from the earliest days of this new period. Former colonial powers maintained a military presence in their former colonies while the US became increasingly interested, in the 1960s, in establishing outposts of their own, crucially making aid and loans contingent on that presence. Strategic military relationships with African nations such as Liberia, as early as the World War II period, established the precedent of US aid and infrastructure-building in exchange for arms, infrastructure naturally geared towards US interests. Aid in all forms expressed US strategic aims, directed in the early years of independence disproportionately to those nations with large US investments such as the resource-rich Congo-Kinshasa (later Zaire) and Nigeria.

Not coincidentally, those countries identified for their strategic importance for their investment potential tended to also be on the receiving end of concerted US intervention, notably the Congo, where the United States and Belgium secretly funded the assassination of Congolese radical nationalist leader Patrice Lumumba in 1961. As Renton, Seddon, and Zeilig describe, Lumumba believed that “independence would not be sufficient to free Africa from its colonial past; the continent must also cease to be an economic colony of Europe.”62 Lumumba declared in his famous “Independence Speech” that, “The Congo’s independence is a decisive step towards the liberation of the whole African continent.”63 This stance, and the ties he forged with the USSR, were received with alarm by Western powers anxious to ensure that the Congo was neither pulled into the Soviet orbit nor became a beacon for revolutionary nationalism.

Coups and other forms of intervention allowed the United States to deepen the vulnerability of new African states so as to pursue their imperial objectives. In 1966, on the heels of the Ghanaian coup, the government established formal ties with the International Monetary Fund, later to be the bearer of devastating structural adjustment policies.64 All told, American fingerprints can be found on numerous assassinations and secret ops in Africa throughout the Cold War.65

In the economic realm, the US aimed to extend its influence through global financial institutions such as the World Bank and the IMF (founded in 1944 with heavy US support) which used private and public loans to impose their financial terms on the rest of the globe and ram through protective trade barriers to open up new markets on terms favorable to the West.66 Shrouded in the soft language of aid and development, the terms of these global financial institutions belied the intentions of extending the subordinate role of African economies into the new era. Africa must accept, declared World Bank president Robert McNamara, “tax measures” and a “choice of projects that might be politically unpopular,” while demonstrating a “willingness to accept and implement advice from outside experts.”67

The colonial powers were compelled to “give up” state power in three-quarters of the continent. The process of decolonization tended to reproduce relatively strong ties between the new nation and the former colonial powers when they were able to establish trade and political agreements on terms favorable to themselves prior to departure68—i.e., where anticolonial resistance did not prevent the departing powers from “disengaging” on their own terms.

The US had a particular advantage of appearing as seemingly free of the colonial legacy. Ideological veneer notwithstanding, the US was able to benefit from the political and economic relationships established under colonialism by the older powers, while likewise benefiting from the loosening of the monopolistic ties of the colonies to their colonial “home.” In this climate, the United States was able to project its power relative to both the continent’s new nations as well as those few that had remained free of colonial domination. As early as 1951, the Truman administration and the Imperial Ethiopian government signed an agreement promising “to cooperate with each other in the interchange of technical knowledge and skills and related activities designed to contribute to the balanced and integrated development of the economic resources and productive capacities of Ethiopia.”69

Certainly these challenges and contradictions of nation building were not lost on the anticolonial movements and new national leadership of the postwar period. For left-leaning nationalists, the dangers of the grip of the West were understood to be of paramount importance. For Ghanaian national leader Nkrumah, neocolonialism threatened self-determination and unity among the new nations of Africa, which, in the pan-Africanist view, shared a common interest in regional integration and economic development. So as Nkrumah wrote in 1964, for example,

Now that African freedom is accepted by all . . . as inescapable fact, there are efforts in certain quarters to make arrangements whereby the local populations are given token freedom while cords attaching them to the “mother country” remain as firm as ever. . . . The intention is to use the new African nations, so circumscribed, as puppets through which influence can be extended over states, which maintain independence in keeping with their sovereignty. The creation of several weak and unstable states of this kind in Africa, it is hoped, will ensure the continued dependence on the former colonial powers for economic aid, and impede African unity. This policy of balkanization is the new imperialism, the new danger to Africa.70

Fanon, from a different perspective, also described the double-edged sword of the process of decolonization and the legacy left by the “departing” powers:

The apotheosis of independence becomes the curse of independence. The sweeping powers of coercion of the colonial authorities condemn the young nation to regression. In other words, the colonial power says: “If you want independence, take it and suffer the consequences.” The nationalist leaders are then left with no other choice but to turn to their people and ask them to make a gigantic effort. . . . [E]ach state, with the pitiful resources at its disposal, endeavors to address the mounting national hunger and the growing national poverty.”71

Of major importance for the US was the goal of ensuring cheap imports of raw materials. And although US investment in Africa was, in reality, a very small proportion of total US foreign direct investment (FDI)—and smaller than the size of investments of the other major powers—the rate of increase of private investment from the US was actually greater in Africa than elsewhere on the globe. Investment in Africa increased by 3.5 times during this period, while US global FDI less than doubled in the same period.72

The objectives of US imperialism did not unfold without opposition, and the white settler regimes were an important case in point. Yet at a time when international criticism was mounting against the South African government, a large bulk of US investment at the time continued to go to South Africa; the majority of investments was in the extractive industries, or in infrastructure to facilitate extraction. By the mid-1970s, US policymakers explicitly acknowledged the urgency of managing political risk vis-à-vis the international apartheid regime so that US and South African capital retained “control of the richest and most strategically important part of Sub-Saharan Africa.”73 Despite growing condemnation of apartheid rule, at the time the value of US investment in South Africa was approximately one-third of total investment in Africa, and increased by 300 percent from 1960 to 1975.74 Given the importance of this economic relationship, the US was content to side-step opposition to apartheid, despite the knowledge that “there was little evidence that US firms deliberately adopted a socially conscious policy of avoiding support of the South African Government or its apartheid policies.”75

In the end, the priority of foreign capital on extraction was no different in South Africa than elsewhere on the continent, priorities that decisively shaped how infrastructure was deployed. For example, investment in electricity and power generation was heavily geared towards digging mines and wells. Laying railroad track, digging harbors, and laying roads were similarly oriented on moving African exports of raw materials abroad. The same can be said for aid in the form of loans. Thus, given the unevenness of natural resources across the continent, development along these lines tended to be concentrated in particular areas, for example, in the Congo or the racist states of South Africa and Rhodesia (as it was known at the time, later renamed Zimbabwe).

The development project

The legacy of colonialism reproduced a political and economic straitjacket for the newly independent nations from the beginning. Competing economic ideologies of the postindependence societies battled over whether development would proceed along free-market or state-directed lines. As Marxist Nigel Harris describes in The End of the Third World:

Poverty was not inevitable, nor could the problem of poverty safely be left to the normal working of the world market. . . . The group of poor countries, identified as “underdeveloped” in the late forties, could not afford to await the possible long-term effects of free trade. . . . There were two different conceptions of economic development. On the one hand, the orthodox economists, known as “neoclassical,” envisaged a world economy in which different countries played specialized roles and were therefore economically interdependent. . . . The radicals, on the other hand, saw national economic development as a structural change in the national economy rather than a relationship to the world economy. . . . With a fully diversified home economy, it was thought, self-generating growth was possible on the basis of an expanding home market, regardless of what happened in the world at large. The starting-point for these preoccupations was the attempt to explain why the orthodox theory of world trade did not work for the poor countries—why for them, it apparently produced impoverishment.76

For advocates of national development, economic uplift could only be achieved by extricating Africa from the capitalist system. Championed in the Arusha Declaration by Tanzanian nationalist Julius Nyerere under the name ujamaa (meaning “extended family,” or “brotherhood”)—and picked up by prominent Marxist intellectuals such as Rodney—African Socialism was embraced by some nationalist leaders as models for the underdeveloped world. The strategic vision of national development—of rapid progress and industrial development—was, for both the African bourgeoisie and the Left, inseparable from key political questions. Its adherents embraced the model of economic development and industrialization they observed in the USSR, typically the path for states emerging from colonialism in that colonialism in that era.77 “In many cases new leaders appeared speaking the languages of ‘socialism’ or ‘humanism’; they would harness the toiling masses behind the efforts of the state, and state-planned economic growth would take place, eliminating poverty, exploitation, inequality and suffering.”78

Socialist Leo Zeilig describes how, following the Soviet Union, “Independence represented a race for top-down, autonomous industrialization in scores of emergent nations . . . [where] state capitalism offered the magic key to development.”79 African ruling classes emphasized state investment and national development based on import-substitution industrialization—that is, diversifying domestic production in order to make economies less dependent on foreign imports to compel development of local manufacturing, sometimes described as “industrialization at the periphery.” And as Harris similarly describes, a diversified economy required the central mobilization of capital resources, coherent direction and coordination from above: “For such an economy to be reasonably self-sufficient at a tolerable level of income, it would have to reproduce domestically all the main sectors of a modern economy. . . . Such a strategy could only be implemented by the state; its control of external trade and financial transactions was the key to reshaping domestic activity.”80

For theorists of “neocolonialism” like Walter Rodney, “the remedy to dependence lay in the delinking of the former colonies from metropolitan capital by revolutionary nationalist regimes. In practice, however, such few attempts as were made invariably ran aground on the shoals of Western hostility, impractical economics, lack of developmental alternatives, self-interested leadership, and the demobilization and subversion of revolutionary regimes.”81

The heavy reliance on state intervention was a feature not only of decolonization in Africa, but of the rapid and uneven transition from predominantly agrarian, feudal societies to concentrated industrial development. Statification was the order of the day: “Indeed in the post-war world, above all in the 1950s, 1960s, and the early 1970s, the use of the state to centralize capital and to push development forward, leapt ahead as never before—above all in the newly emerging third world nations.”82

Harris notes that, ironically, “With decolonization, the removal of a former imperial ruling order (as in much of Asia and Africa) vested unprecedented power in the hands of the new states. It is scarcely to be wondered that, as Trotsky observed in tsarist Russia, ‘Capitalism seemed to be an offspring of the state.’”83 By the end of the 1970s, public-sector investment in less developed countries comprised over half of total investment. Nationalized corporations in places like Ghana and Zambia reflected around 40 percent of GDP.84

Despite the expressed political ideology and aspirations, independent economic growth was severely challenged in Africa for a number of reasons. For one, instances of successful economic development, acquired in the prior (colonial) period, were a product of a relatively high level of integration into the world system. This integration translated into hesitancy on the part of some regimes to embark on some of the hallmark tasks of the national development project, such as import-substitution, nationalization of industry, and redistribution of previously colonial-held land. Agricultural production, meanwhile, was retooled so as to focus on exports, with a dramatically negative impact on subsistence farming and consumption by the majority.

Peter Binns’s account of revolution and state capitalism in the Third World describes this contradictory dynamic where, conversely, weaker states could more easily attempt the nationalization project given their position of weaker connection to the world system. Binns provides, writing in 1984, the following example to illustrate the point:

South Africa currently provides Zimbabwe with a quarter of its imports and trans-ships fully one half of all the rest of its trade. The import-substitution industries built up in 1965–79 are no exception to this situation. . . . Mugabe’s government has therefore neither moved significantly against the white landowners nor attempted to do anything that might provoke South Africa into cutting Zimbabwe’s life-line to the outside world. In contrast with Mozambique whose very backwardness made such a policy feasible for a few years, the relative economic strength of Zimbabwe and its greater integration into the world market has, paradoxically, been the very feature that prevented such a policy being possible there.85

Attempts at autonomous national development also faltered soon after independence as a result of the sheer economic weight of economic poverty—that is, the size and scale of capital resources that needed to be marshalled both to develop, and to protect, fledgling industries, were prohibitively high. On top of this, Western powers took steps to ensure that African nations could not establish a basis for economic independence. Intervention aimed at undermining economic development took up a range of strategies that included extending and reinforcing unfavorable trade policy from the colonial era to limiting foreign investment to areas that would directly facilitate extraction.

Binns makes note of another important factor in the weak economic footing of the newly independent nations and the tendency towards state-directed economies during the 1950s and 1960s, that of changes in foreign investment patterns:

The pattern of international investment and trade changed quite dramatically; before the war around 40 percent of world trade was in primary products—agricultural produce, fuel, and raw materials—but by the end of the long boom this figure had fallen by a half. International trade became much less a matter of exchange between primary producers on one hand and manufacturers on the other, and much more a question of the mutual exchange of manufactures between relatively industrialized nations or parts of nations. This meant that international capital flowed increasingly from one industrialized part of the world economy to another; American capital, for instance, found many more opportunities for profitable investment in advanced Europe than in . . . Africa.86

Import-substitution also produced its own problems: for one, domestic manufactures were expensive compared to more competitive imports. By the same token, low interest rates intended to drive industrial investment created not only high-priced goods, but also very few jobs as well as industrial overcapacity, despite the symbolic value of heavy industry signaling advancement. Many Third World nations, especially in Africa, were hobbled in their ability to overcome these obstacles: “Only some large countries could pursue such policies, and only for limited periods of time in given historical circumstances. Sooner or later, if growth were to continue, the domestic accumulation process—whether wholly or partially in the hands of the state—would have to be reintegrated in the world process.”87

By the 1970s, many of the assumptions of the national development model came to be questioned. The “cures” had come to be seen as the source of the problems of underdevelopment. Theorists such as Baran, Amin, and Gunder Frank correctly argued that national planning and import substitution were bound to fail without revolutionary change in the class structure. Internationalists such as Michael Kidron placed their critique within a Marxist framework by arguing that economic development required revolutionary change on a global scale, not merely within national borders: “Removing the old ruling class, nationalizing the means of production (and expropriating foreign capital), redistributing income and land, forced accumulation, would not suffice to overcome the paralysis imposed by the changed structure of world capitalism.”88 For Kidron, the size and scale of major industrialized powers left weaker ones unable to compete.

By the close of the era of national development, the poorest countries “remained trapped in producing and exporting a single raw material at low levels of productivity, lacking reserves to guard against the ravages of famine. The triumphs of world capitalism were indeed more spectacular in the less developed countries than they had been in the more developed, but victories in the long march of capital accumulation should not be confused with the conquest of hunger.”89

New ruling classes were now called upon to manage “their own” working classes so as to pursue the project of national development of industry and agriculture. Yet working classes across the continent—only recently at the helm of anticolonial struggles—were unwilling to suffer these new attacks silently. In postindependence Nigeria, for example, the government’s calls to unite for “national development” were unsuccessful at papering over their assaults from above or deflecting the rise of class-consciousness and class divisions in the general strike of 1964. Similarly, Zambian mineworkers battled attacks by the new government that were also mounted in the name of national development, while the years following independence in Zimbabwe saw strike waves for wage hikes and social reforms. As elsewhere, new rulers such as Zambia’s Kenneth Kaunda and Zimbabwe’s Robert Mugabe faced off workers’ militancy with repression and co-optation.90

The critical issue, ultimately, was not merely one of sell-outs and political betrayal. Ultimately, the contradictions of “African socialism” and the process of turning the reins of the accumulation process over to indigenous capitalists were unsustainable. In the African case, the weak basis of African capitalism, as well as the pressures of the world system, compelled an accommodation with foreign capital. Attempts to establish the advantage of local capitalists ran up against the resistance of capital, a strategy ultimately that couldn’t be overcome with a strategy of national development from above.

Conclusion

Ultimately, state capitalist/national development models failed in Africa, both in their ability to overcome the legacies of colonialism and specifically in their inability to create nations able to grow while seeking to delink from the world capitalist system. “The third worldist ‘socialist’ vision of utilizing the state against capital and the multinationals is . . . not only a hopeless dream, but has been made dramatically more so by the sharpening competition and increasing internationalization of the world capitalist system itself.”91 The brutal reality of these dynamics and the compulsion of the world market were borne out in the coming decades: the collapse of the USSR formalized for many regimes a shift from state-directed model to free-market capitalism, even those leaders in Africa previously hailed as “Marxist” such as those of Angola, Benin, and Ethiopia.92 The contradictions of these political and economic legacies—the weaknesses of the new national leaders and the newness of the postcolonial state, and above all the pressures of the international economy—thrust regimes toward abandoning the most militant or “socialist” projects. For example, “In the southern African revolutionary states—Angola, Zimbabwe and Mozambique— . . . revolutionary regimes, often established after a long and bitter guerrilla war, have performed a remarkable about-face and have ended up with a series of very significant accommodations with western capital.”93

In this context, the Left and the organized working classes of Africa were compelled to learn this project’s lessons the hard way. The task of building genuine revolutionary socialism from below was to be postponed. The combined pressures of the legacies of colonialism, the Stalinist development model, and the restrictions imposed by Cold War imperialism proved impossible to transcend. “An incidental byproduct of the process was that the left, in the name of socialism, was subverted,” notes Harris, “and bent to the tasks of supporting and defending the process of national capital accumulation in the name of national liberation. It was a harsh process, and required radical terminology to conceal it.”94

The requirements of the continent’s new ruling classes—accentuated by the structural constraints inherited from colonialism—could by no means escape the competitive pressures of the broader system, particularly as it lurched into crisis. It is to the mass-based workers’ struggles and social movements of today that we must look to find a way out of this impasse.

- Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth (New York: Grove Press, 1963), 27.

- Eric Toussaint, Your Money or Your Life: The Tyranny of Global Finance. (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2005), 30.

- Remarks by the President to the Ghanaian Parliament, July 11, 2009, https:/whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/remarks-president-ghanaian-parliament.

- Christine Lagarde, “Nigeria: Act with Resolve, Build Resilience, and Exercise Restraint,” IMF, January 6, 2016, https://imf.org/external/np/speeches/2016/010616.htm.

- Jubilee USA, Unmasking the IMF: The Post-Financial Crisis Imperative for Reform, October 2010, http://jubileeusa.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Resources/IMF_Report.pdf.

- Matina Stevis, “Angola to Seek IMF Aid to Cope with Looming Financial Crisis,” Wall Street Journal, April 6, 2016; Matina Stevis, “IMF’s African Push Reopens Old Wounds,” Wall Street Journal, February 20, 2016.

- Peter Binns, “Revolution and State Capitalism in the Third World,” International Socialism 2:25, Autumn 1984, 37–68.

- Lee Wengraf, “False Pledges to Africa in the Crisis,” ISR 67, September 2009, http://isreview.org/issue/67/false-pledges-africa-crisis.

- Catherine Blampied, “African Governments Must Take Responsibility on Poverty,” Financial Times, October 6, 2014.

- Carey L. Biron, “Africa ‘Net Creditor’ to Rest of World,” New Data Shows, IPS, May 28, 2013.

- Patrick Bond, “Is Africa Still Being Looted? World Bank Dodges Its Own Research,” Links International Journal of Socialist Renewal, August 15, 2010.

- “Doctors’ Dilemma,” Economist, November 26, 2004.

- World Health Organization, Meeting the MGD Drinking Water and Sanitation Target: The Urban and Rural Challenge of the Decade, 2006.

- World Health Organization, Water Sanitation Hygiene: Key facts from JMP 2015 Report, http:/who.int/water_sanitation_health/monitoring/jmp-2015-key-facts/en/.

- World Bank, Africa Development Indicators, 2007–2008.

- African Development Bank, African Economic Outlook 2014: Global Value Chains and Africa’s Industrialization, 168.

- John Ghazvinian, Untapped: The Scramble for Africa’s Oil (New York: Harcourt Books, 2007), 19.

- Mike Davis, Planet of Slums (London: Verso Books, 2006), 164.

- Paul Collier, The Bottom Billion: Why the Poorest Countries Are Failing and What Can Be Done About It (London: Oxford University Press, 2008).

- Charlie Kimber, “Aid, Governance and Exploitation,” International Socialism 107, June 27, 2005.

- Gavin Capps, “Redesigning the Debt Trap,” International Socialism 107, June 27, 2005.

- Peter Dwyer and Leo Zeilig, “An Epoch of Uprisings,” chap. 3 in African Struggles Today: Social Movements Since Independence (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2012).

- Mahmood Mamdani, Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996), 74–75.

- Dwyer and Zeilig, “An Epoch of Uprisings.”

- See Mamdani, Citizen and Subject.

- Roger Southall and Henning Melber, eds., A New Scramble for Africa? Imperialism, Investment and Development (Scottsville, South Africa: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2009), 41.

- Nigel Harris, The End of the Third World: Newly Industrializing Countries and the Decline of an Ideology (London: Meredith Press, 1987), 168.

- David Seddon, “Historical Overview of Struggle in Africa,” in Leo Zeilig, ed. Class Struggle and Resistance in Africa (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2009), 81.

- Fanon, Wretched of the Earth, 12.

- Ekuru Aukot, “Northern Kenya: A Legal-Political Scar,” Pambazuka News, Issue 401, October 9, 2008, http://pambazuka.org/en/category/comment/51035.

- Munyonzwe Hamalengwa, “No Land, No Freedom,” Pambazuka News, Issue 726, May 14, 2015, http://pambazuka.org/en/category/comment/94717.

- David Seddon, “Historical Overview of Struggle in Africa,” 78.

- Bob Fitch and Mary Oppenheimer, Ghana: The End of an Illusion (New York and London: Monthly Review Press, 1966).

- Kwame Nkrumah, “Neocolonialism in Africa,” in The Africa Reader: Independent Africa (New York: Vintage Books, 1970), 217–18.

- Mamdani, Citizen and Subject, 25.

- Walter Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (Washington, DC: Howard University Press, 1981), 262.

- Ibid., 216.

- Ibid., 262.

- Ibid., 279–80.

- Ibid., 25.

- Frederick Cooper, Africa Since 1940 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), 16.

- Chris Harman, “The End of Poverty?” Socialist Review, Issue 297, June 2005.

- Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, 231.

- Third Report of the Economic Commission for Africa, Economic Conditions in Africa in Recent Years, United Nations, 1969.

- Ibid.

- UNICEF, “The 1960s: Decade of Development,” in The State of the World’s Children 1996, http://unicef.org/sowc96/1960s.htm.

- Frederick Cooper, “Modernizing Bureaucrats, Backward Africans, and the Development Concept,” International Development and the Social Sciences: Essays on the History and Politics of Knowledge, (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1997), 64–92.

- Fitch and Oppenheimer, Ghana: The End of an Illusion, 45.

- Ibid., 70.

- Ibid., 47.

- Elise Huillery, “The Black Man’s Burden: The Cost of Colonization of French West Africa,” 2012, http://econ.sciences-po.fr/sites/default/files/file/elise/Black_Man_Burden_20june2012.pdf.

- Ibid.

- Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, 245.

- Ibid., 206.

- Frank Church, Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Study Mission to Africa, November-December 1960: Report. Washington: US Govt. Printing Office, 1961, 22.

- Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, 205.

- Mamdani, Citizen and Subject, 104.

- Sidney Lens, Forging of the American Empire, From the Revolution to Vietnam: A History of US Imperialism (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2003), 349.

- Frantz Fanon, Wretched of the Earth, 35.

- William F. Komer, special assistant for national security affairs, 1966, cited in Charles Quist-Adade, “The Coup That Set Ghana and Africa 50 Years Back,” Pambazuka News, Issue 764, March 2, 2016, http://www.pambazuka.net/en/category.php/features/96756.

- Yao Graham, “Nkrumah: Model Challenge for Ghana’s Rulers,” Pambazuka News, Issue 438, June 18, 2009, http://www.pambazuka.net/en/category.php/features/57083/.

- David Renton, David Seddon and Leo Zeilig, The Congo: Plunder and Resistance (London and New York, Zed Books, 2007), 85.

- Patrice Lumumba, Speech at the ceremony of the proclamation of the Congo’s independence, June 30, 1960, at https://www.marxists.org/subject/africa/lumumba/1960/06/independence.htm.

- Abayomi Azikiwe, “The Re-emerging African Debt Crisis: Renewed IMF ‘Economic Medicine,’” Pan African News, November 23, 2015.

- Cf. William Blum, Killing Hope: U.S. Military and CIA Interventions Since World War II (Monroe, ME, Common Courage Press, 1995).

- Lens, Forging of the American Empire, 350–351.

- Robert McNamara interview in The Banker, March, 1969.

- One example is the preparations by Belgian capital for the end of colonialism in the Congo. See David Renton, David Seddon, and Leo Zeilig, The Congo: Plunder and Resistance (London and New York, Zed Books, 2007), 127.

- Cited in Alemayehu G. Mariam, “Financing for (Under)Development in Africa? How the West Underdeveloped Africa and is Now Trying to ‘Finance Develop’ It,” Pambazuka News, Issue 737, July 29, 2015.

- Kwame Nkrumah, “Neocolonialism in Africa,” 217.

- Fanon, Wretched of the Earth, 54.

- Survey of Current Business, August 1963, October 1968, and 1971.

- Dick Clark, U.S. Corporate Interests in South Africa: Report to the Committee on Foreign Relations, (United States Senate, Washington: US Government Printing Office, 1978), 5.

- Ibid., 8.

- Ibid., 10.

- Nigel Harris. The End of the Third World: Newly Industrializing Countries and the Decline of an Ideology (London: Penguin, 1987), 13–14.

- Zeilig and Seddon, “Marxism, Class, and Resistance in Africa,” in Class Struggle and Resistance in Africa, 27.

- Peter Binns, “Revolution and State Capitalism in the Third World,” 37.

- Tony Cliff, “Deflected Permanent Revolution,” posted April 23, 2010, http://www.isj.org.uk/?id=641.

- Nigel Harris. The End of the Third World, 118.

- Southall and Melber, 10.

- Binns, “Revolution and State Capitalism in the Third World,” 51.

- Nigel Harris, The End of the Third World. 160. Along similar lines, Fanon wrote in The Wretched of the Earth: “The national bourgeoisie has the psychology of a politician, not an industrialist.” See Mireille Fanon-Mendès-France, “Frantz Fanon and the current multiple crises,” Pambazuka News, Issue 561, 2011, http://pambazuka.org/en/category/features/78515.

- Nigel Harris. End of the Third World, 163.

- Binns, “Revolution and State Capitalism in the Third World,” 46–47.

- Binns, “Revolution and State Capitalism in the Third World,” 53.

- Harris, End of the Third World, 143.

- Ibid., 23.

- Ibid., 117.

- Leo Zeilig, Class Struggle and Resistance in Africa. See chap. 5, Miles Larmer, “Resisting the State: The Trade Union Movement and Working-Class Politics in Zambia, 1964–91,” and chap. 7, Munyaradzi Gwisai, “Revolutionaries, Resistance, and Crisis in Zimbabwe,” 219–51.

- Binns, “Revolution and State Capitalism in the Third World,” 64.

- Zeilig and Seddon, “Marxism, Class, and Resistance in Africa,” 46–50.

- Binns, “Revolution and State Capitalism in the Third World,” 38.

- Nigel Harris, End of the Third World, 186.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Google+

Google+ Tumblr

Tumblr Digg

Digg Reddit

Reddit StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon