Editorial

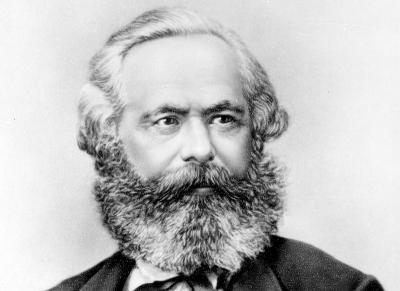

The key feature that distinguishes Karl Marx’s conception of socialism from that of previous radicals, as Anthony Arnove notes in “How Marx became a Marxist,” is the understanding that the working class—whose labor is the life-blood of capitalism—is not merely a suffering class, but the class whose conscious “self-activity” can liberate all those oppressed and exploited under capitalism and truly transform society. This message of workers’ power has always been important, but its relevance becomes clearer in times when the working class is in motion.

As we mark the bicentennial year of Karl Marx’s birth, the relevance of workers’ self-activity is confirmed in the recent strike of the West Virginia teachers who shut down the state’s entire school system. The victory of these teachers has inspired a wave of similar struggles in other areas sometimes derided as “Trump country.” The teachers aren’t just fighting against substandard pay—they are fighting to save public school systems and other public-sector workers from being eviscerated by state legislators in anti-union, “right-to-work” states.

At the same time that teachers are putting the “movement” back into the labor movement, the Supreme Court is on the verge of (and may have done so by the time this issue is published) permitting all public workers to opt out of joining unions and paying agency fees for representation in collective bargaining agreements—essentially institutionalizing right-to-work policy at the national level. In “A Radical Road to Labor’s Revival?” Lee Sustar looks at the parlous state of the labor movement today, its deep erosion by decades of employer attacks and business unionism, and the possibilities for its revival. “What is needed,” Sustar concludes, “is a rediscovery of the left-wing, militant unionism of the CIO era, often called social movement unionism, which made the strike a weapon and won wide working-class support radiating from the point of production into the community.”

In tandem with Sustar’s piece, readers should look at Geoff Bailey’s interview with Kim Moody, author of a new book On New Terrain. Moody discusses not only the structural changes in the US working class and the implications of these changes for rebuilding a working-class movement based on rank-and-file power; he also discusses the importance of developing a political alternative for workers that is independent of the Democratic Party. “It’s important for socialists in . . . movements to argue,” says Moody, “not just to throw our support behind a better-than-average Democrat, but to think about how the disruptive power of direct action movements can translate into grassroots political organization.”

The themes of Marx and the contemporary relevance of his ideas is continued in articles by Phil Gasper and Elizabeth Terzakis. In “The Materialist Conception of History Revisited,” Gasper examines Marx’s ideas of historical development and change, which are sometimes interpreted by critics to argue that Marx was a historical determinist. Against these arguments, Gasper looks at Marx’s conception of the “forces of production” and the “relations of production” and explores the dynamic relationship between them in the constitution of a specific “mode of production.” History doesn’t make people; people make history.

In “Marx and Nature,” Elizabeth Terzakis shows that far from focusing solely on “economics,” Marx and Engels were deeply concerned with the impact of capitalism on the metabolic relationship between humans and the natural environment. As she writes, “nature is crucial to Marx’s definition of labor, and the disruption of the human relationship with nature is an integral feature of capitalism.” Indeed, as she notes, “Marx believed that one of the human needs not being met by capitalism was the need for a direct and appreciative relationship with nature and a whole lot more free time through which to develop it.” Only a society based on the democratic planning of the associated producers, she concludes, can restore a healthy, sustainable relationship between human beings and the planet.

It would be tempting to see Trump’s verbally belligerent and seemingly erratic foreign policy as simply a reflection of his outsized yet delicate ego. But as Ashley Smith shows in his article “The Trump Administration’s Strategy for US Imperialism,” there is a method to Trump’s madness. His foreign policy remains “very committed to American dominance in the world, but in a far more unilateral fashion than ever before.” US policy reflects a contradiction that goes beyond who is sitting in the White House. Washington’s status as the world’s dominant power has eroded, largely in the face of a rising China. The United States finds itself unable to fully embrace its previous approach of “superintending” neoliberal free trade globalization, and is therefore groping toward policies that, while aiming at shoring up its positions around the world through other means, also have the potential to further destabilize the world balance of power. As Smith summarizes, “The Trump administration’s National Security Strategy reorients US imperialism away from the so-called War on Terror toward containment of great power adversaries, naming them explicitly as China and Russia, and adopts a confrontational approach to regional rivals like Iran and so-called rogue states like North Korea.”

In an article translated by Lance Selfa and Eva Maria, Josep Maria Antentas, a professor of sociology at the Autonomous University of Barcelona and a member of the editorial board of Viento Sur, analyzes the development and current state of the Catalán independence movement. He roots the crisis over Catalonia in the general crisis of the Spanish state stemming from the negotiated end to the fascist Franco dictatorship.

Books reviewed in this issue include Roxanne-Dunbar Ortiz’s Loaded: A Disarming History of the Second Amendment; US Politics in an Age of Uncertainty edited by Lance Selfa; Steven Stoll’s Ramp Hollow: The Ordeal of Appalachia; and Kim Moody’s On New Terrain. Also reviewed are several recent books on women’s oppression and feminism, including Social Reproduction Theory, edited by Tithi Battacharya; Cordelia Fine’s Testosterone Rex; and How We Get Free: Black Feminism and the Combahee River Collective, published on the fortieth anniversary of the CRC Statement to bring their crucial insights to a new generation of activists. Also of note are reviews of a classic study of Italian autonomism, Storming Heaven, and a new book by Palestinian journalist and activist Toufic Haddad, Palestine Ltd.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Google+

Google+ Tumblr

Tumblr Digg

Digg Reddit

Reddit StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon