The rise and fall of New World slavery

Robin Blackburn teaches at the New School in New York and the University of Essex in the United Kingdom. He is a member of the editorial committee of New Left Review and the author of many books, including The Making of New World Slavery: 1492-1800, The Overthrow of Colonial Slavery: 1776-1848, Age Shock: How Finance is Failing Us, and Banking on Death. He has just published two new books, The American Crucible: Slavery, Emancipation and Human Rights and An Unfinished Revolution: Karl Marx and Abraham Lincoln, both published by Verso. He spoke to the ISR’s Anthony Arnove in May 2011.

HOW DOES The American Crucible: Slavery, Emancipation and Human Rights fit in relationship to a series of books you’re writing on the making and overthrow of slavery?

WELL THIS latest book, The American Crucible is an overview of the entire rise and fall of the slave regimes of the Americas from the early sixteenth century to the end of the nineteenth century. My previous two books on slavery in the New World covered a substantial part of that period but did not deal with the rise and fall of the nineteenth century slave systems in Cuba, the United States, and Brazil. The Crucible seeks to explain why slavery could continue to grow even after suffering defeat in the Caribbean and in the former Spanish colonies.

So quite a lot of the material in this new book is itself new. And where I’m reprising what I’ve already covered, I do so with new evidence and from the perspective of the whole extraordinary story. The Making of New World Slavery was about the original building of these colonial-era regimes, while The Overthrow of Colonial Slavery dealt with their destruction in the “Age of Revolution,” 1776–1848. Those are both substantial works, so what I do here is offer a broad synthesis tracing the contradictory impact of capitalist growth on the one hand and the surge of antislavery politics on the other, with the Haitian Revolution of 1791–1804 being the central event, breaching the slave systems but also clearing an opening for new producers in the U.S. South, Brazil and Cuba.

It is this contradictory development that I focus on in this new book. Slaveholders knew they faced the danger of revolution, but they were determined to exploit the ruin of what had been Europe’s main supplier of plantation products. As they moved to take advantage of high prices and eager consumers, they also moved to strengthen their own security, both by heightening repression and by reaching out to new allies.

Across the whole field there has been new research, so I’m able to update the argument on earlier developments as well as cover new ground. I try not to duplicate things I’ve already covered in those earlier books and hope that they work together to cover four hundred years or more of events of great significance. I still have a further book to go which will be on the U.S. South, Brazil, and Cuba in the nineteenth century.

COULD YOU discuss the degree to which slavery was vital to the economic growth and expansion of the United States?

WE HAVE to start with the colonial period. Already around 1770 the English colonies of North America were a vital part of Britain’s Atlantic system, which was itself the forcing house of British capitalism and its Industrial Revolution. British and North American merchants supplied American planters with slaves, equipment and provisions while, in their turn, the plantations produced a stream of vital commodities—especially cotton, sugar, tobacco, and coffee—all of them items which helped to reproduce wage laborers in a new way. In The Making of New World Slavery, I argued that this dynamic Atlantic nexus of trade and credit sustained a regime of “extended primitive accumulation,” a breakthrough to genuinely capitalist production in the metropolis but based on an expansion of slavery in the plantation zone. The American Revolution momentarily interrupted this so-called “triangular” trade linking Africa, Europe, and the Americas, but its medium and long-term impact was to break down barriers to free trade and to widen the markets available to U.S., Cuba and Brazilian planters.

When The Making of New World Slavery was published in 1997 many scholars denied that slavery had made an important contribution to British industrialization and capitalist growth. I argued against this then-prevailing view, and I’m glad to say that a lot of the more recent research is bringing further evidence of its importance.

In 2002 Kenneth Pomeranz published The Great Divergence, which furthered the argument by looking for the ways in which slavery, colonialism, and Britain’s “empire of free trade” allowed Europe to annex vast areas of land—what he calls “ghost acreage”—in the Americas, to overcome the severe space constraints in Britain and Europe. Thus British textile manufacturers were able to buy slave-produced cotton that could not have been produced in Europe. There are three or four other studies like Pomeranz’s, which all go to strengthen the view that American markets and raw materials made a really vital contribution to industrial advance. The planters, their brokers, and merchants were also crucial sources of credit helping to finance canals, railroads, and steam ships. So far discussion has focused on British industrialization, but in The American Crucible I look at the ambivalence of the role of slavery in U.S. industrialization, as a source of credit as well as cotton. But a credit system comprising many thousands of banks also proved a source of instability while the Southern market was inherently limited by slavery, because slave needs were met by their own efforts on the plantation.

In The Crucible, I try to weave together a story relating to the hybrid structures of Atlantic accumulation with attention to the wars and revolutions that were transforming this space in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. I see the great plantation boom as sowing the seeds of conflict between colonial elites and the metropolis—and later between a new “picaresque proletariat” and the planters and their bourgeois hangers-on in New York and London.

The maritime strength of the early U.S. republic allowed its merchants and captains to play a large role in dismantling the Spanish, French, and Portuguese colonial systems in the years 1783–1825. The British also wanted to open up South America, but they found that the United States had the initiative so far as land-based expansion was concerned. In the book, I scrutinize the imperial conflicts that contributed to this, especially the Louisiana Purchase (1803) and Mexican War (1846–48). It is often not realized that the British and North Americans vied with one another for the spoils of “free trade” and continued to feed the growth of the dynamic slave systems of Cuba and Brazil long after the supposed banning of the Atlantic slave trade in 1808.

After 1808, U.S. and British West Indian planters were unable to import new slaves from Africa, and those in expanding areas had to rely on a “domestic” slave trade. But Cuban and Brazilian planters continued—legally or clandestinely—to buy huge numbers of captive Africans, amounting to as many as 40,000 annually in the 1840s. Spanish colonial institutions and the structures of the Brazilian Empire proved as well adapted to the expansion of plantation slavery as those of the North American republic.

HOW USEFUL—or not—do you find the concept of “Atlantic history”?

I DON’T often use the term myself, but I do welcome the attempt to get beyond narrow national historiographies. That’s the important thing. Of course, beyond a certain point one would need to broaden out and see the link between the Atlantic, the Indian Ocean, and the Pacific, and the systems of trade and commerce that flourished there. But when we are dealing with the New World slave systems, the Atlantic is really the decisive space. And of course there’s a lot of interaction between the different bits of the Americas, the different parts of Europe and between Europe, Africa, and the New World. The rubric of Atlantic history helps to bring out the transnational impulses of the ages of revolution, capital, and empire.

And if I have a regret it’s that I’ve not been able to follow up my brief account of the buying of captives on the African coast with a detailed account of its impact on the thousand or more African societies that were affected, to show the consequences of that trade over three or four centuries; but it’s something that I certainly intend to go into more deeply. Prior to about 1700, African exports of palm oil, gold, pepper, and other such items were more valuable than slave purchases, but the scale of the traffic grew to over a hundred thousand a year in the second half of the eighteenth century. The Europeans were fuelling African wars and favoring the more predatory social formations by selling guns and cutlasses to them. By the late eighteenth century, the British were selling as many as a quarter of a million guns every year, fostering a slave-raiding cycle.

The Atlantic perspective helps us to see the transnational, or multinational, character of the slave-related trades after 1815. The U.S. North was as much a part of this as the U.S. South. While there was only a trickle of illegal slave imports to the U.S. South, U.S. capital, U.S. ship builders, and merchants from New England, New York and from the Mid Atlantic states continued to be engaged in the Atlantic slave traffic. Over the period 1818–65, about two and a half million new slaves were brought across the Atlantic. Cuban and Brazilian merchants certainly played the major role, but they seem to have received extensive help from the North. U.S. merchants built ships for the slave trade, and they supplied trade goods for exchange on the African coast. So U.S.-built vessels, flying a variety of flags, bought textiles and metal goods. They dodged the British Navy’s anti-slave trade squadron, and the rather token U.S. squadron sent to suppress the illegal traffic, and finally carried tens of thousands of African captives to Brazil or to Cuba. Many of the slave goods were British-made and exported to Brazil by merchants who were good at catering to the tastes of the traders on the African coast.

The dimensions of this trade were very large, but at present we do not have an exact figure for U.S. participation. The U.S. consular authorities in Brazil estimated that about a half of the slaves brought in the Empire each year came aboard U.S.-built ships. The British Consul in Havana reported a smaller but still sizable traffic to Cuba. So this is an important area in which the scholarship is still advancing.

HOW WOULD you characterize the link between slavery and the overall U.S. and Atlantic economy in the early and mid-nineteenth century?

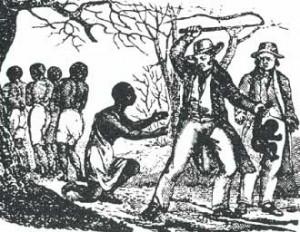

PLANTATION SLAVERY was a form of “primitive accumulation,” as described by Marx in the first volume of Capital, being a form of exploitation based not on wage labor, but on the direct appropriation of the labor of the exploited. Some have understood Marx to be referring to a phase or epoch, which was to be surpassed by industrial capital. Instead what we see is an intermeshing of different types of labor extraction, some based on the wage form and others based on forced labor. Industrialization stimulated the demand for cotton, and the slaveholding planters proved adept at opening up new territory and boosting cotton output. They intensified two mechanisms for raising slave output, the slave gang and the task system. The overseers and slave drivers used the gang to set a fierce pace of work. They used stop watches to establish what could be produced in a given time—and the whip to ensure that it was. The drivers had a range of sanctions but history was to show that the whip was integral to the slave systems.

I call the intensified systems of slave exploitation a regime of “extended primitive accumulation,” feeding industrial growth. Wage labor and capital could not appear everywhere all at once, so early industrialization has to make do with transitional forms of appropriation and typically intensifies the labor process, using forced labor and sweated labor. The term “market revolution” is useful because it draws attention to the shadow cast by the process of commodification in sectors which are themselves still pre-industrial but are having to adjust to industrialization. For farmers and artisans this was a time of great stress as they got into debt or sought to cope with price shocks, expensive and high freight charges. Planters, though much richer, shared some of these problems, hence their occasional spasms of hostility to the banks.

The slave economy of the U.S. South was important because it was providing one of the prime inputs to the Industrial Revolution and helping to establish the beginnings of new popular consumption norms outside the plantation zone, based on sweetened beverages and cotton clothes. The Starbucks and jeans culture, if you like. The arguments that apply to Britain apply also to North America, with slave-grown cotton being of crucial importance. From the manufacturers’ point of view, cotton was greatly preferable to wool because it was easy to adapt to industrial processes. The U.S. planters adopted and improved the cotton “gin,” enabling them to spread cultivation to the inland area, especially the vast Mississippi basin acquired between 1804 and 1848.

Also, of course there was the decisive role of steam power. Steam was harnessed to grind sugar in Louisiana and Cuba, to bale cotton, or to carry the cotton and the sugar by steamboat or by railway to ports, and later to propel ships across the Atlantic. Slave toil was providing vital inputs to the most advanced sectors to the economy and diversifying consumption. These new methods made the slavery of this epoch rather profitable.

The planters, the slaveholders, needed credit to get the crop into production. On the other hand, they would keep their account balances and their profits with intermediary institutions, such as banks and brokerages. Just to mention one name, Lehman Brothers, the famous bank that collapsed a couple of years ago, began life as a cotton brokerage in the antebellum U.S. South. And at this time, the financial institutions would supply large amounts of credit to early manufacturers and to planters and farmers caught up in the market revolution.

There was also then, quite a web of interpersonal lending and borrowing of credit between individuals and between families and between generations. That’s an important dimension of the story, which I’d like to go into in much more detail. So what we’re talking about here is the contribution of capital and credit. While slave-produced raw materials and consumer items helped to broaden markets in the North and North West, in the plantation slave South formal markets were weak, as the planters forced the slaves to meet many of their subsistence needs themselves. They cultivated a corn crop and also worked their own garden plots.

This means that slavery is associated with relatively shallow markets. But there is some evidence that planters were finding that it made sense to buy food from the North and to even in some ways discourage cultivation of subsistence crops on the plantation itself. Instead, they could devote more land to the cash crop by buying increasingly cheap wheat from the American Midwest.

That could help to explain something that is a bit puzzling. When the South seceded and established the Confederacy, the Southern economy was afflicted with quite severe famines and shortages. So the Mississippi planters may have bought wheat and other supplies from the North and Northwest, in order to focus the forced labor of the slave gangs on the cash crop as much as possible. The plantation economy absorbed capital and credit and created only a limited market for consumption goods. The South did not share in the industrial advance of the North, with only a tenth of total U.S. manufacturing capacity being in the South by 1860.

Another intriguing aspect of the plantation economy of the South is that it appears to have included a quite extensive informal economy or “black market,” with its own special currency. Archaeologists excavating the slave quarters have found large numbers of beads and other tokens that perhaps were used to facilitate exchanges in the slave community and between different plantations. I furnish some evidence for this in The American Crucible. For example, around 90,000 beads have been found hidden away in root crop cellars in the slave quarters at Andrew Jackson’s Hermitage plantation near Nashville. Beads were used in personal adornment, but perhaps also a sort of currency. Other finds include dozens of tiny brass or porcelain clenched hands, perhaps serving as bearers of friendship and good fortune.

WHAT DO you consider to be the unique or special features of the form of slavery that takes place in the United States, compared to other forms of slavery?

THERE ARE several answers to that question. Slavery was largely concentrated in the rural sector in North America, whereas there were many slaves in the colonial cities of Latin America and the Caribbean. Where it was found, urban slavery was likely to allow a little more autonomy to the slave.

Another major contrast is that the slave population in North America was unusual in that it replaced itself and grew even without slave imports. I argue in The Making and The Crucible that this demographic buoyancy was owed partly to a healthier climate and partly to the fact that North American planters organized food production, reassuring slave women that if they had children they would not starve.

The growth of the slave population in North America reflects somewhat easier physical conditions, but the subjective conditions of enslavement were very intense, especially if contrasted with the early Spanish and Portuguese slave pattern. In Portuguese and Spanish America there were quite high manumission rates. Over half of all persons of African descent were free by 1650, with many working as masons, barbers, bakers and itinerant peddlers, and with many urban Afro-Americans, free and slave, belonging to their own religious brotherhoods.

Until about 1815, the slave condition was not so permanent or so racialized in Latin America as it was in the South, but after that date a more exacting pattern of quasi-industrial slavery came to Brazil and Cuba too. Slaves were then mobilized for agriculture, working in gangs according to a relentless rhythm. The centrality of the plantation and the permanent quality of slavery is something that eventually became a shared feature of the slave regimes of the Americas.

THE HISTORIAN Eric Williams, whose work you cite in The American Crucible, argued that “slavery was not born of racism: rather racism was the consequence of slavery.” Is that your view, as well?

I CERTAINLY agree that the rise of the plantation system did greatly intensify and focus racial beliefs and ideologies. However, it didn’t create them from nothing, and the racism generated by the slave regime was not the same as the racial feeling that allowed it to develop in the first place. Pre-existing racial ideas and perceptions were somewhat chaotic and some of them were even hostile to allowing the entry of Africans. But the plantation revolution created intense demand for labor. Europeans believed that someone had to perform the very harsh toil of the plantations and were relieved that slaves were available to do it. The suffering of the slaves during the “Middle Passage” from Africa also revealed racial disregard. The loading ratios on slave trading vessels were three times as great as on ships bringing indentured servants from England.

In the first place we have to explain the attitudes and conduct of merchants and of planters, since they were the architects of the plantation regime. The ordinary colonists had a lesser degree of power and responsibility. Many left the plantation colonies as planters resorted to slave labor. The planters had to pay high wages to overseers, slave drivers, and so forth to induce them to stay. Ultimately the whole colonial order required a level of endorsement from the ordinary people who were not enslaved, above all the whites. So there were various levels of complicity in the construction of a racialized order. These were not democratic societies, so we can’t give our severest censure to those who constructed the slave order. But the fact that Europeans awarded greater recognition and respect to fellow Christians, to fellow Europeans and to fellow whites, was something that helped to make possible the building of the slave plantations in the first place. Once that regime already existed, it became a source of great profit and of livelihood to many and that persuaded them to stifle any reservations they might have. There was also a powerful element of fear. There was the guilty sentiment that “we’re treating these people badly,” accompanied by the fear that the captives would strike back, that they were looking for any chance to escape, to revolt, or to help an enemy. This fear was widespread. It was known that there were major slave outbreaks in Jamaica every ten years or so, for example. And so this was something that continually nourished this fear. And there were important slave conspiracies and revolts—fewer than in Jamaica, but still a significant number—here in the North American colonies.

The whites felt that if there is going to be a slave uprising, the slaves are going to target the generality of the white community; they will see almost any white person as complicit in their oppression. And to some extent that perception was an accurate one. Certainly fear furnished cement for the colonial and slave regime. Fear as well as privilege; privilege is important too. And these various factors intensified and focused racial feeling in new ways.

In the seventeenth century and early eighteenth century, racist practices are defined by citing stories from the Bible, such as when Noah places a curse on the offspring of his son Ham. He curses the children of Ham to be “servants of servants,” according to the King James Version. This curse was later mapped onto African peoples and was sometimes still offered to justify racial enslavement in the nineteenth century.

But by the nineteenth century, you get the beginning of pseudoscientific accounts that invoke a “great chain of being,” with the superior whites at the top and then a sort of great gradation down to lesser forms of humanity and the animal kingdom. The earlier religious justifications are not completely abandoned, but they’re adapted and supplemented when slavery is challenged by the French and Haitian Revolutions and by British emancipation in the 1830s. In reaction to the new universalism of antislavery there are pseudo-scientific and pseudo-anthropological studies that claim to register the inequality of the different branches of mankind.

While race loomed large in defenses of slavery, so too did two other major considerations. Firstly, slaves were private property and property was sacred; and secondly, the plantations were a major source of national wealth and could not be deprived of a labor force without weakening the nation. In The Crucible I argue that these powerful ideologies became vulnerable only at times of revolutionary or proto-revolutionary crisis.

YOU FOCUS extensively on the importance of the slave revolution in Haiti. Could you describe its global importance and impact?

FOR THE Atlantic world, and for the Americas as a whole, the Haitian revolution is the first breach in the slave regime. The early abolitionist agitations had been checked after receiving some small-scale victories outside the plantation zone. Prior slave revolts had also been defeated. However, that slavery might be a fault line of Atlantic political and moral economy was registered by the beginnings of popular abolitionism in Britain in the 1780s. The first wave of abolitionism—whether in the United States, the English Colonies, or France—was blocked. The whole issue of the future of slavery and the slave trade was posed in a new way by slave revolt in Saint-Domingue, but it took over a decade for the emancipation program to triumph against a succession of deadly foes—the French royalists, the Spanish, the British, and finally Napoleon Bonaparte.

The great slave uprising of August 1791 in Saint-Domingue did not instantly lead to emancipation, but it did create the elements of a Black military power. The French republicans—faced with royalist treachery and British invasion—saw the advantage of appealing to the slaves by offering them emancipation. The novel idea of “general liberty” helped to forge an alliance between Toussaint Louverture, the Black general, and Sonthonax, the Jacobin commissioner. In The Crucible I trace the complex interweaving of ideas from Europe, Africa, and the New World that eventually allowed Haiti to become the first state in the world completely to ban slavery. I also show how revolutionary France gave vital help to the “Black Jacobins” of the Caribbean. The very title of C.L.R James’s great book gives a role to a new revolutionary vision born in the crucible of the battle against slavery. In my book I draw attention to the fact that the alliance between revolutionary France and the new Black power in Saint-Domingue actually lasted a few years, with the Thermidorean leadership playing quite a radical role—even sanctioning a war on slavery in the Caribbean, a “quasi-war” with the United States, and a republican uprising in Ireland. So it took Robespierre to back revolutionary emancipation, but the policy continued to be pursued, with historic consequences, for five or six years after his downfall. The British and U.S. leaders eventually persuaded Napoleon Bonaparte to abandon the revolutionary policy, but it was too late; emancipation and the new Black power were too powerful, too rooted in the great mass of the formerly-enslaved.

The eventual victory of the Haitian Revolution helped to re-invigorate the British abolitionist movement and to alarm slaveholders throughout the hemisphere. Saint-Domingue had been the most valuable European colony in the hemisphere. The British lost 80,000 men in the Caribbean theater, and Napoleon 50,000 trying to restore slavery. Haiti was a very poor state, and maintaining its independence was costly, but embattled as it was, it still held aloft an aspiration to racial freedom and equality. In 1816 the president of Haiti, Alexandre Pétion, helped Simon Bolivar to relaunch his struggle for the independence of Spanish South America in return for a promise to end slavery there. The antislavery measures later taken by the South Americans were limited to a ban on the slave trade and a “free womb” law, freeing the children of slave mothers once they reached their twenties, but these moderate measures were sufficient to prevent the growth of new slave systems in the lands. I further think it is interesting that the first systematic attack on racial ideology was to be written by a Haitian scholar and statesman, Anténor Firmin in 1882.

So the survival of the Haitian Revolution was at the time seen as a hugely important event. It sowed fear among the planters but also alerted slave owners in all parts of the Americas. It helped to persuade British planters to compromise with emancipation in the 1830s.

But in the United States, Brazil, and Cuba, there is—and this is one of the major themes of The Crucible—a reconfiguration and relaunching of the slave systems. The French and British Caribbean slave regimes, based on Caribbean islands and with massive slave majorities, had proved too unstable. In French Saint-Domingue in 1790 or Jamaica in 1830, slaves comprise nine-tenths of the population, and there are nearly as many free people of color as there are whites. Given the intense political and social conflicts of the time, this is not sustainable. Slavery is swept away by a complex class struggle combining slave revolt and abolitionist agitation.

However, on the mainland and in Cuba, both with sizable white and/or free populations, emerges a “new American Slavery” based on plantation expansion. It becomes quite rare for slaves actually to outnumber the free, and certainly not on the scale seen in the Caribbean. The free population is organized in militia and patrols. They are usually able to overpower any revolt in a few days. On the other hand, the planters are able to use steam power and parcels of slaves to open up huge inland areas to plantation production. The new slave regimes had survived the “age of revolution” and were adapted to the steam age.

The destruction of Saint-Domingue—until then the largest producer of plantation crops in the Americas—and the trade boycott of Haiti, creates a huge open market for all the sugar and coffee and cotton that used to come from that colony. Slave revolt and abolitionist agitation combine in Britain’s Reform crisis in the 1830s to free the slaves in the British West Indies. I draw on the work of Edward Thompson to show how antislavery mobilizations in Britain and the colonies helped to extract a major concession in 1833—and one mobilization that was further radicalized in 1838. However, under the terms of British emancipation it was the planters, not the former slaves, who received compensation.

But, paradoxically, with the ending of slavery in British and French Caribbean, and the closing of much of Spanish South America to slavery, we see a rise, not a fall, in slave numbers and the value of slave output. Between 1815 and 1860, the slave population of the Americas doubles and plantation output triples.

The U.S. historian Dale Tomich has called this “the second slavery,” and in fact there is a research network of historians in the United States, Brazil, and Cuba who are researching the modernization of the slave systems that ensued in the early- and mid-nineteenth century. By 1860, there are six million slaves in the Americas, and the crops they produce comprise over two-thirds of the hemisphere’s total exports. There were at least 40,000 slaveholding planters in the United States, ten thousand in Brazil, and over two thousand in Cuba. They were among the richest and apparently most powerful people in the world, and saw themselves as the power behind the throne of “King Cotton” and “King Sugar.”

In the book, I give some estimates of the rising value of the trade in slave produce. I show this rising strongly in the early and middle decades of the nineteenth century. However, I also draw attention to the fact that the rise in the absolute value of slave-based commerce conceals a decline in its percentage of total world commerce. The industrial advance in these decades and the wide reach of the “market revolution” among the farmers of the North and Northwest is outstripping the still-impressive growth of the plantations.

There’s a huge accumulation process underway in North America and parts of Europe, and this is beginning to overtake the growth in the slave-based regions, which remain stuck in a type of monoculture. The New World slave economies are very strongly, almost exclusively, organized around the cash crop, around cotton, sugar, coffee, and a few other minor crops. Industrial methods and wage labor could be adapted to a variety of products and services, producing a much broader pattern of socio-economic development than the narrow specialization of the plantation and slave mobilization. In the plantation context, the slave gang delivered results, but it had no special edge in general agriculture or manufacturing.

There is another aspect of the growth of slavery to consider, namely the fears that it aroused outside the slave zone. The success of the slaveholders of the U.S. South in opening up new territory in the trans-Mississippi West alarmed many in the North who saw them grabbing land that Northerners might aspire to settle. Hostility to the so-called Slave Power also focused on how the Southern elite had a firm grip on federal institutions. Abolitionists were never more than a small minority of Northern opinion, but many Northerners became “free soilers,” or at least resented the Fugitive Slave Laws which obliged them to help the slave-catchers. The churches and the political parties began to split along sectional lines.

IN YOUR study An Unfinished Revolution: Karl Marx and Abraham Lincoln, you discuss the centrality of the idea of “self-emancipation” to Marx’s thinking about slavery. The agency of slaves themselves in ending slavery has often been overlooked in historiography.

THAT IS true. There has been a narrative of antislavery and abolition in Britain and the United States that was really an all-white narrative. When the American Historical Review hosted a debate in the 1980s on the origins of humanitarianism and antislavery, their contributors did not devote any attention to Black antislavery. The debate was full of interest—I’m not trying to say it wasn’t a fascinating debate in its own way—but the Black contribution to antislavery sentiment was ignored.The debate was published as a book in 1992. So twenty years ago the Black contribution to antislavery could still be overlooked. I think in the last two decades things have changed a very great deal. African-American agency is being recognized. I think the attention given to the Haitian Revolution is part of this awareness.

Black witness and Black abolitionism were in fact central to the development of white abolitionism, especially the more radical currents of white abolitionism. White abolitionists acquired deeper understanding of the slave regime by reading the life stories of Olaudah Equiano, Mary Prince, Frederick Douglass, William Wells Brown, Linda Brent and about one hundred others.

African Americans told their story, under their own initiative or when invited to do so by abolitionist editors. They gave an account of their bitter experiences and of their attempts to escape from slavery. This literature became central to the whole moral idea of the abolitionist movements. While written for a public already willing to criticize slavery, the accounts given of unending toil, of systematic and wanton punishment, and of the break-up of slave families was in many ways detailed and convincing.

Furthermore, the abolitionist press, such as the Liberator edited by William Lloyd Garrison, was sustained by subscriptions from the free Black community in the North, numbering about a quarter of a million by 1850. Garrison was able to keep this publication going for twenty-five years in part because he had widespread support from free Blacks in the North. They seem to have been around half of the readership of this periodical. The free people of color in the North also supported a Black convention movement and a number of Black churches. Frederick Douglass and other leading black orators went on well-attended speaking tours and spoke from the platform at antislavery conferences. Women, both black and white, also played an active role in the antislavery movement.

In The Crucible, I’m looking at the pattern across the Americas as a whole, and so the Black contribution to antislavery varies from place to place. In Spanish South America and Cuba, colored military men are of great importance. In the Spanish-American wars of independence, it is striking that about a half of the liberation forces were of African descent. Nationalist ideology allowed men of color to become senior commanders, and many were happy to throw off the colonial yoke, as that yoke went together with slavery. But Black commanders were discouraged from championing specifically Black interests. In Brazil there were many colored journalists and lawyers who played a prominent part in attacking slavery. In the United States, 180,000 Blacks, most of them former slaves, fought in the Union army, though only a hundred received commissions, mostly as chaplains or doctors.

I document the impact of revolts in the British colonies, contributing to the eventual emancipation in the British islands. By this time the slave rebels are aware of antislavery in the metropolis, and there is the element of a dialogue. There are sections of English opinion that responds to events in the colonies, and there are sections of the slave community aware of metropolitan controversies. For example, in British Guiana in 1824, the revolt has the character of an armed demonstration. They ask to parley with the governor, and to put a list of demands with the Governor, and to speak over the heads of the planters to the governor, and eventually to the British Parliament. And there are members of Parliament, who in the debates on emancipation in the British parliament, refer to the conduct of the slaves on the plantations and the way that it’s not just a senseless upsurge of violence, it’s actually aimed at freeing themselves, at emancipation, which is a goal that English people also can understand.

I go through all the emancipation processes, one after another. The pattern varies a lot, but there is always some contribution from the slaves themselves. The Haitian case is exceptional, but the Afro-American role always has to be taken into account.

In Unfinished Revolution I look at the contribution made by the so-called “contrabands” in the U.S. Civil War, in pressing Lincoln and Northern commanders to adopt antislavery objectives. Following the outbreak of war, slaves began to flee from Confederate territory to the Union Army camps and some commanders adopted the term “contraband” to justify making use of these refugees in a variety of support roles. The swelling numbers of contrabands created a pressure for an emancipation policy and an Emancipation Proclamation. Abolitionists such as Wendell Phillips argued that it was absurd not to enroll the contrabands in the Union Army. In a famous speech in Washington in 1862, he pointed to the military prowess that had been displayed by the former slaves in Haiti. He observed that the Almighty had placed a thunderbolt in the hands of the North if it wished to defeat the rebels, and that was emancipation. I reprint the article where Marx celebrates this observation in Unfinished Revolution. Marx detected a powerful current of self-emancipation amongst African Americans.

This is a concept that Marx begins to develop in the 1860s. It contrasts to the way that he has previously argued, where he assumes that the slaves are so oppressed, so deprived of rights and possibilities, so much in the shadow and control of their owner, that they would find it impossible to develop a broad resistance to slavery. Slaves don’t have rights of association, for example, or rights of free speech. This line of thought is not without some element of truth, and it echoes pessimistic observations by Frederick Douglass.

But at the same time, it probably misses the ways in which the slave community did actually organize in and against the slave regime, and was sometimes able to set some limits on planter power and establish some networks of communication. Throughout the Americas, the advent of a crisis in the ruling order allowed slave rebels and revolutionaries to find ways of attacking or weakening slavery. In 1860, as the secession crisis unfolds, Marx becomes attentive to signs of slave resistance. His interest in the history of slave revolt is stimulated. He writes in a letter to Engels that he’s reading Appian’s history of the Spartacus uprising. He finds in this Egyptian author of the third century A.D., that the slaves, following their revolt, melt down their chains and use them to forge new weapons. Now, that’s probably poetic license on the part of Appian, but anyway it’s the sort of detail that Marx likes. He writes to Engels saluting Spartacus as a “leader of the Ancient proletariat” who inflicted defeat on four Roman generals and held out for two and a half years. The revolt is eventually only defeated by Crassus organizing really huge forces and concentrating the whole might of the Empire and of his own private wealth on the struggle. When one of Marx’s daughters in 1865 asked him who is his favorite historical figure, he replies “Spartacus,” a sign of the change in his attitude toward slaves.

At the same time, Marx is getting interested in movements among American workers, and in particular, the eight-hour day struggle. It’s just at this time that he’s also writing or redrafting the chapter on the length of the working day in Capital.

I think that the significance of U.S. struggles around the length of the working day is something that explains his concentration on this topic. He is also drawn to analyze wage labor. In his draft for chapter 6 of the first volume of Capital, he focuses on the reproduction of the worker on an expanded scale, including the cultural reproduction of the worker under a free wage labor system. The wage worker is very exploited but still has an element of discretion and choice. For example, newspapers are part of the basket of goods they can purchase.

In the communications of the International to its North American sections in the late 1860s, there is a stress on the priority for the workers’ movement of securing rights of trade union organization, of free speech, of free education, and of cultural development. This is part and parcel of strengthening the organization of workers, and struggle for these intermediary democratic goals is extraordinarily important. This is also very much the case in the plantation zone itself after emancipation and in the period of Reconstruction, and with the battles over Reconstruction in the late 1860s with new ideas of rights.

Also a fascinating phenomenon that I discuss in The American Crucible and An Unfinished Revolution is the role of African Americans in deepening the language of rights. Black conferences in Syracuse, upstate New York, in 1864, and later in South Carolina and Louisiana, adopted a “Declaration of Rights and Wrongs,” which goes beyond the standard list of abstract rights and targets particular racist abuses and oppressions. In 1868 the Constitutional Convention in Louisiana responds by adopting what they call “public rights,” which seek to establish rights of public access to means of transportation such as trains and buses, and to places of accommodation, boarding houses, and hotels. These rights are enshrined in the Louisiana constitution but later become a dead letter when the federal government withdraws its support for Reconstruction in 1877.

In drawing attention to African-American agency, we have to be aware of its limits. There is a self-emancipation dynamic, but it doesn’t carry all before it. African Americans are a minority, albeit a large one, and they need allies. The Republican Party at its most radical arms former slaves and abolishes slavery. But it fails to organize powerful, racially mixed state militia to defend Reconstruction and to foil the Ku Klux Klan and other racist vigilantes. It also fails to distribute land to the freedmen. So African Americans have allies who fail them. And they face enemies who have not been completely defeated. The Confederate army is not absolutely defeated.

The rebel commanders decide to surrender, and are allowed to do so. The officers can keep their side arms, and they can keep their horses. Surrender of that sort, “surrender with honor” as it were, is a little bit different from being just completely beaten. And of course few former Confederates are arrested and imprisoned, whatever their treason. For a short time, Jefferson Davis is imprisoned, but generally speaking, they get off very lightly and the various limitations placed upon them are soon lifted.

Notwithstanding real achievements during Reconstruction, the end result is eventually Jim Crow and a hugely oppressive racial regime. Obviously, the African Americans are not responsible for this, but they are let down and abandoned. It’s their allies who are too weak. Some abolitionists believe too much in the juridical importance of the suppression of slavery. The abolitionist societies disband soon after the Civil War, and The Liberator closes. Abolitionists found The Nation to continue the struggle for racial equality, but that journal lets them down, as Garrison himself complains.

We should bear in mind that the Radical Republicans who fought to destroy slavery knew little about the detailed conditions of the former slaves. The Republican leaders offered a Southern Homestead Act, without realizing that the freedmen lacked the considerable financial resources needed to bring land into cultivation. There was a very great desire on behalf of African Americans to acquire land, but it was almost universally frustrated, and they had to make do with becoming sharecroppers, which was very much a third or fourth best. One measure of the Republican failure in the South is that its income per head by the 1880s was only a half of the national average.

So, in that sense, the current of Black self-emancipation was important, but it had clear limits. The decision to emancipate was rarely taken purely for its own sake. Republican measures against slavery were sometimes motivated more by the desire to punish rebels than out of real commitment to Black equality. Mixed motives led to mixed results. Nevertheless, an ideal of racial equality was born and acquired a following that was to be of great historical significance. In 1857, the state of Iowa voted to deny the vote to Blacks but in 1868, after a radical campaign, the voters overturned this ruling.

IN AMERICAN Crucible, you make an interesting critique of the “latent virtue” argument, the idea that in effect the capitalist market eventually corrected itself in abolishing slavery.

WHAT I was trying to get at was the false idea that the market, or the state, or organized religion, was built on antislavery principles and all that was required was the patience to allow them to dismantle the regimes of racial slavery whose creation they had abetted in the first place. The received narrative of abolition is that the British monarchy and empire, or the U.S. Constitution, or the Protestant religion, or the free market system, nourished the antislavery impulse. These notions are quite tightly bound up with national historiography, above all in Britain and the United States. Eric Williams once said that reading the British historians, you are led to believe that the British only built up such a vast slave system in order to have the satisfaction of suppressing it.

There are countless books and films that proclaim emancipation as essentially a national destiny or a consequence of the innate virtues of Protestant Christianity. In the 1980s, Thomas Haskell urged in the American Historical Review that humanitarian principles had been nourished by market relations. I certainly do not deny that a brave minority of patriots, Protestants, and businessmen did eventually support antislavery. But Black resistance played a part, as did the agitations of white radicals, with many of the latter also challenging the existing state, established religion, or the sacred status of private property. Patriots, religious radicals, and progressive bourgeois played a positive role, but the success of the antislavery almost everywhere required pressure from slave resistance and a broader popular movement.

It is important to register the mobilizations of free workers and farmers against the slave system, and that antislavery sentiment was often prompted by fear of market forces, and especially by fear of the combination of slavery with a free market.

Artisans and laborers saw slavery as a threat to their own liberties, sometimes for quite idealistic reasons, and sometimes for quite narrowly self-interested reasons. They didn’t want to see planters claiming land in the West, for example, and they feared the “Slave Power.”

The whole process of emancipation was not a gradual unfolding, but rather a continually contested and uneven struggle over the rights that should be enjoyed by the direct producers. It’s marked by stiff resistance on the part of the slaveholders, very often supported by their own bourgeois allies in cities such as New York. For example, in the 1830s, the abolitionists were completely set upon in many parts of New England by self-described “gentlemen of property and standing,” and they were beaten up, tarred and feathered, and chased out of town. These self-described gentlemen were not slaveholders, but they were people who were extremely alarmed that abolitionism was a threat to the Union, and an insult to the two major parties, which supported slavery.

So basically there was a broad attempt to contest the advance of antislavery, and there was a deep conservatism, but when the society as a whole faced fundamental choices and some combination of war, revolution, or civil war, the supports of slavery were weakened. Respect for private property, racial animosities, reactionary conceptions of national interest—all of these could be redefined in new terms. Of course the working out of the revolutionary crisis is different in France, Britain, the United States, and Brazil, and I only offer a rather schematic account in these books. It’s a subject to which I hope to return.

At all these times, everything is up for grabs, and the existing order must reorganize itself, make fundamental changes. Otherwise, it’s not going to survive. And that’s the context. So it’s a context that takes place within this container of the nation state. But each national entity is caught up in a broader movement. What happens in Britain is deeply influenced by North American victory, by the Jacobin Republic, the struggle with Napoleon, by South American revolution, and so forth. And likewise, events in France are affected by what Britain is doing, or in the United States by what is happening across in Europe and in the Caribbean. The fate of slavery in Cuba or Brazil is bound up with the outcome of the U.S. Civil War.

YOU WRITE in your study of Lincoln and Marx that you were led to rethink your views of the impact of Marx on the United States.

WHEN I was working on The American Crucible, I came across a lot of material relating to Marx and Lincoln and to the Civil War and Reconstruction. I knew that Marx supported the North, of course, and that he had written for the New York Tribune. What I didn’t realize is that he had written 400 articles for the Tribune. In fact, he wrote even more, but 400 of them were published. I did not know that the young Marx had thought of emigrating to Texas and had obtained an emigration license. I didn’t realize how closely he followed American affairs. I knew some of his remarkable articles about the Civil War, but I didn’t know all of them. So all this made quite an impression on me, and I think I have already referred to the way that the events in North America even had an impact at a conceptual level on his analysis of the length of the working day, or his use of the term emancipation. I was also unaware of the impact of the International Working Men’s Association in the United States in the aftermath of the Civil War.

I was impressed by the role of the German-American veterans of the 1848 revolution in the immediate antebellum period. I knew Joseph Weydemeyer as one of Marx’s correspondents in the United States. I didn’t realize Joseph Weydemeyer was an important labor organizer in the 1850s, founding a Workers Association open to all workers, regardless of their sex or race. Nor was I aware that he played a role in the emergence of the Republican Party in the Northwest. In fact, the radical German Americans played a key role in the battle for control of St. Louis on the eve of the war. This city had a major arsenal. The mobilization of a 4,000-strong German-American militia was responsible for defeating a rebel attempt to capture that arsenal. As a Union Army colonel, Weydemeyer was later charged with organizing the defense of the city.

About 200,000 German Americans fought in the Union Army, and former members of the Communist League rose to senior posts. I wasn’t aware of their military contribution. In the antebellum period they had helped to distance Republicanism from temperance, a cause that weakened the attraction of the Republican Party for many immigrants. For German Americans, slavery was the main issue, not alcohol. Even Lincoln was a supporter of temperance. But this was something that was going to limit the appeal of the Republican Party for Catholic immigrants.

The story of 1848 spills over into North America in the 1850s and 1860s, and this is one of the reasons that Marx sees the antislavery struggle in the United States as central to building the International Working Men’s Association. Marx’s Address to Lincoln in 1865 and Lincoln’s reply via the U.S. ambassador are significant moments in this story. Indeed, the American sections of the International took off in the late 1860s, and labor organizing made good progress for a while, eventually leading to gigantic labor battles in the 1870s and after. Europe at that time had not witnessed strikes on the scale of the great strike of 1877. Once again, events in St. Louis are very interesting. The city becomes one of the major epicenters of the strike. The strikers keep the railroad going during the strike under their own management, rather than just stopping everything. There are African Americans in the leadership of the strike, a fact that recent research has brought to light. Marx and Engels were very stirred by these developments.

So the story is a fascinating and interesting one. Many currents of North American anticapitalism—anarchists and syndicalists, as well as socialists—drew inspiration from Marx’s writings. And in other continents the struggles of U.S. workers supplied vivid images of “robber baron” capitalism, of vigilantism, and of fierce resistance to employers. The Haymarket massacre furnished International Workers’ Day.

But the fragmentation of the exploited within the United States and the failure of Radical Republicanism doomed many of Marx’s hopes. The “Unfinished Revolution” to which the title refers is as much Lincoln’s as Marx’s. Lincoln had presided over the suppression of slavery, but his successors had allowed a new regime of racial domination to be built in the South. The Republicans failed to establish the rule of law in all parts of the republic. Indeed, in each region, vigilantism played a role, terrorizing former slaves, or labor organizers, or immigrants of Chinese or Hispanic origin. The world of the “robber barons” and their political tools was a travesty of Lincoln’s ideal.

But in organizing military supplies and war finance, Lincoln and his cabinet had relied too much on the private sector and Wall Street. They had failed to back Schuyler Colfax’s call for a tax on capital. After the war, a section of the Republican leadership shrank from radical measures and soon tired of Reconstruction. The Southern elite was allowed to regain political importance and to assist in a weakening of the regulatory function of the federal state. Income tax was declared unconstitutional, there was no central bank to discipline Wall Street, and the Fourteenth Amendment was interpreted as defending the rights of corporations, not former slaves.

Paradoxically, the weakness of the (bourgeois) federal state made it far more difficult to propose a labor party or a welfare state. The abandonment of Reconstruction was a crucial turning point, frustrating the best hopes of radicals, egalitarians, and social democrats of many different hues. There were occasional regional breakthroughs for a farmer-labor party, but nothing of national scope.

Marx had been right to glimpse the possibility of more far-reaching changes arising out of the Civil War. At the outset of the conflict, the gap between North and South was small, even on slavery. Lincoln and the Republicans only wished to prevent the territorial expansion of slavery, and were willing to agree to amendments that would have furnished elaborate protection to existing slave holdings far into the next century. Lincoln was emphatic that the North was fighting only to save the Union.

Marx, however, had a structural understanding of the conflict, explaining that the South was impelled to fight because Northern expansion was loosening the veto power of the slaveholders in Washington. Their grip on federal power was threatened. Whatever the timidity of Northern aims, Washington would be driven—Marx believed—to transform the war for the Union into a war against slavery. Marx was also persuaded that the defeat of the slaveholders might open paths to the founding of a workers’ party and to a raft of radical democratic measures. This was not to happen, but the eruption of massive labor struggles, the successive and overlapping challenges launched by the Populists, the Socialists, and the Industrial Workers of the World, all showed that his hopes had a real purchase on the destiny of the United States in those critical years. My introduction sketches the pattern of success and failure, and the documents I assemble are just a small sample of the remarkable voices that were raised at this time.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Google+

Google+ Tumblr

Tumblr Digg

Digg Reddit

Reddit StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon