Class war in Longview

WHILE 2011 saw revolutions and general strikes erupt internationally and the Occupy Wall Street movement swept the United States, the small city of Longview, population of 36,000, in southwestern Washington state quietly turned into ground zero for one of the most militant US labor struggles in decades.

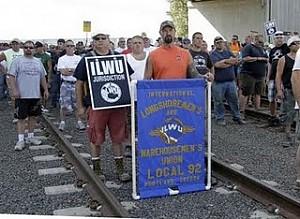

Since May 2010, the 200 members of International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) Local 21 have been escalating the fight in a two-year-plus battle to force the multinational conglomerate EGT Development to honor its grain-contract and use ILWU labor at a new $200 million grain terminal in Longview. This is the first new terminal built on the West Coast in the last twenty-five years.

In the course of the battle there, ILWU members and their supporters have organized mass pickets of hundreds to block trains from bringing grain to the terminal. But the company and the state have taken a hard line. Local 21 is up against multiple global corporations, police and private security, the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), and another union—Operating Engineers Local 701, which is providing scab labor.

Roots of the struggle

The story starts in early 2009 when EGT Development, after five years of planning, announced its new grain elevator would create 50 new longshore jobs and employ local workers to construct the plant.

However, EGT used both nonunion and out-of-state labor to build the elevator. Still Local 21 expected that its almost 80-year jurisdiction in the west coast grain industry, which operates under a separate contract from the dockworkers agreement with the Pacific Maritime Association (PMA), would be respected and longshore members would be allowed to run the terminal.

But a close look at the multinational corporations behind EGT shows how profit at any cost won out. EGT is a joint venture of Japan-based ITOCHU Corporation, South Korean STX Pan Ocean, and White Plains, N.Y.-based Bunge Limited. While ITOCHU ranks 201 on Fortune’s Global 500 list of the world’s largest corporations, Bunge, ranked number 182, is the 51 percent controlling partner in EGT. It has operations that span five continents and thirty-seven countries, with profits of $2.5 billion in 2010. ITOCHU provides logistics while STX is the shipping arm of this partnership.

As Dan Coffman, president of Local 21, put it, “Bunge is part of what we call the grain cartel, which is the equivalent of the oil cartel. There’s a handful of players in the grain cartel, and Bunge is one of them—along with Cargill, Archer Daniels Midland, Louis Dreyfus, and Gavalon. Actually, if you look at it, they’re probably more powerful than the oil cartel, because people have to eat, and they know that.”

Bunge’s CEO, Alberto Weisser, sits on the boards of International Paper, PepsiCo, and the Council of the Americas.

The company has used its political influence to benefit from “big” government entitlement programs. Bloomberg Businessweek reported the US government paid out $15.4 billion in grain subsidies in 2009, 75 percent of which went to three companies, including Bunge.

According to a Reporter Brasil study called “Brazil of Biofuels,” Bunge has been linked to the deforestation of the Amazon rainforests in Brazil and the use of slave labor on its soy plantations there.

One could argue part of Local 21’s fate was connected to the US Commodity Futures Modernization Act signed into law by President Clinton in December 2000. This Act deregulated the trading of “over the counter” derivatives for commodities that are staples of the US grain industry such as wheat, rice and corn. It led to a speculative boom in this industry.

The value of these types of commodity derivatives grew from $440 billion a year in 1998 to over $7.5 trillion in 2007, according to Olivier De Schutter, the United Nations “Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food.”

As a result, food prices rose by 83 percent between 2005 and 2008, with corn prices tripling. Wheat prices increased 127 percent and rice skyrocketed by 170 percent. It was in this climate that Bunge saw mega-profits to be made.

But why did Longview become the target? Coffman thinks in part it’s the small port here and that Bunge thought it could come in and bully Local 21 just as it has other communities around the world.

Jake Whiteside, Local 21 vice-president, pointed out Longview’s important geographical location. “It’s the first place you come to on the Columbia River from the Pacific Ocean. We’re set up with a rail system. I-5 is right there. None of that is a coincidence.”

Coffman sumed up the benefits of the new operation for Bunge: “This new elevator is going to meet their needs logistically to supply them with an easier route to get their product to Southeast Asia and Japan.”

This state-of-the-art facility will pour 40 percent faster than the last elevator built on the West Coast.

“If you can imagine a Panamax ship being loaded in about a 24-hour period, that’s basically unheard of. You’re talking 50,000 to 60,000 metric tons of whatever product is being loaded in a 24-hour or less period. That’s huge volumes at super-fast speeds. These people are recreating the playing field for the grain industry,” notes Coffman.

Contract negotiations, or EGT “dictations” as Coffman likes to call them, started in January of 2010 and finally broke off in February 2011. Instead of the promised fifty longshore jobs, Local 21 was only able to get EGT to agree to seven total jobs.

The two deal breakers were that EGT wanted two 12-hour shifts a day with no overtime pay and to have no longshore union labor in the master console room, where the flow of grain throughout the whole facility is controlled.

“We told them we don’t care if you have fifty supervisors in there,” Coffman explains. There needs to be one longshoreman. We don’t take orders from a supervisor.”

Direct action

In response to EGT’s hard line, the union organized the first of several mass direct actions in July to prevent or delay Burlington Northern Santa Fe trains from delivering grain to the terminal.

On July 13, starting around 11 p.m., more than 600 workers and supporters blocked the tracks and forced a train full of grain back to Vancouver, Washington. Then on September 7, hundreds of longshore workers again blockaded trains, first in Vancouver, then later in the day in Longview. This time, police in riot gear, and equipped with tear gas and rifles carrying rubber bullets, were able to clear the tracks after a four-hour standoff.

In response, around 4:30 a.m. on September 8, hundreds of ILWU members and their supporters allegedly dumped grain from train cars, cut brake lines on trains, smashed windows on a guard shack, and held six security guards hostage, according to the police version of events. Coffman told Longview’s official paper, the Daily News, the claim that unionists took hostages was “a blatant, total, all-out lie.”

Some have said the ILWU used its monthly “stop work” meetings to shut down the entire Ports of Vancouver and Longview on September 7 and the Ports of Tacoma, Seattle and Anacortes on September 8. Others referred to them as unauthorized wildcat strikes.

What’s clear is that these September mass actions took place after the NLRB filed charges against Local 21. On August 29, the NLRB sided with management, demanding an end to what it claimed was “violent and aggressive” picketing by the ILWU.

US District Court Judge Ronald Leighton then issued an injunction against the ILWU. The union is currently allowed only eight people at any time to picket the two entrances to the EGT terminal.

“I think the perception across the nation is that the NLRB is there for labor,” Coffman says. “It’s not. It’s there for corporations, employers, and the rich people.”

Despite the injunction, more arrests followed on September 21 when Coffman and nine mothers, wives, and grandmothers, members of ILWU Local 21’s Women’s Auxiliary #14, engaged in nonviolent civil disobedience by blocking a train attempting to carry wheat to the new terminal.

The cops who arrested the protesters used such brutality that Phoebe Wiest, a 57-year old grandmother, suffered a torn rotator cuff. Two other Local 21 officials were arrested when they tried to come to the defense of her and the others.

One of them was Executive Board member Kelly Muller. He described his experience when he came to Wiest’s defense: “We walk in and all of a sudden they got the mace cans. They hit us—they don’t even give us a warning. Here comes four or five cops. They take us to the ground and are on my back. I hit my head on the railroad track. The cops pried both my eyes open. They spray it into my face and into my mouth while I’m handcuffed.”

“I’m sitting on the railroad tracks and this cop starts jerking on my arm,” Wiest recalls. “I started screaming, ‘it’s hurting.’ I look up and Kelly’s on the ground, on his face and belly. They are spraying pepper spray at him and kicking him.”

This police brutality against Local 21 members is only one instance of a level of repression that the labor movement arguably hasn’t seen in years. There have been seventy-five arrests and 220 citations. According to the Daily News, the union has been fined $315,000.

Police have waited outside union members’ homes until 3 a.m. shining high-beam spotlights into their bedrooms. A member who is a minister at a church was met at his door by police holding an AK-47. Whiteside was arrested while picking up his kids at church.

When asked his opinion about whether the cops are part of the 99 percent, Coffman responded, “To me, the question is: who’re they protecting? They’re protecting the rich who wrote the rules and the laws of this country. They’re protecting the interests of corporations, and those corporations are here to do one thing: make as much money as possible and try to keep working people down as much as possible.”

On September 22, Local 21 filed a civil rights lawsuit against the police, Cowlitz County, and the City of Longview. Since then, the abusive tactics have stopped. As the ISR went to press, the union was taking part in court hearings where dozens of its members were being charged with criminal trespass for their part in the mass direct actions at the railroad tracks.

The union maintains it is protected by its First Amendment right to protest on public, port-owned property.

Local 21 has also had to deal with EGT hiring a PR firm, Atlanta-based Luc Media, and a “Pinkerton” private security firm called Special Response Corporation out of Baltimore. And the scabbing operation of the International Union of Operating Engineers Local 701 out of Gladstone, Oregon continues. Despite this, Coffman made it clear that their battle is with EGT and not Local 701. He knows the bosses would like to see two unions fight each other instead of EGT.

Meanwhile the union has been steadily building solidarity with many different unions as it prepares for the first barge and then later the first ship of EGT product to leave the Port of Longview. As of this writing, EGT still hadn’t announced when the first shipments would be ready.

The strength of the ILWU centers on its control of the hiring hall and its coast-wide dockworkers contract with the PMA, which expires in 2014. The union knows the PMA will be closely watching the outcome in Longview.

Coffman makes it clear that if EGT refuses to use Local 21 labor, “There’s going to be problems. They know it, we know it, the police know it, the Coast Guard knows it. But when you’re dealing with very rich people and very rich corporations, they think they can come into our community and do whatever they want. They’re going to have to think again because the ILWU is not going away in this battle. Never. We will fight until the bitter end.”

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Google+

Google+ Tumblr

Tumblr Digg

Digg Reddit

Reddit StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon