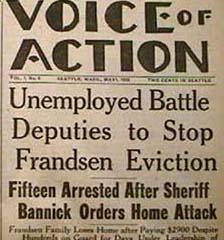

Fighting evictions during the Great Depression

THE GREAT Rent Strike War of 1932 began in a quiet section of the Bronx just east of Bronx Park and west of the White Plains Road elevated line. A neighborhood of modern elevator buildings with spacious rooms, adjacent to a park, the zoo, and the botanical gardens, it seemed an unlikely place for a communal uprising. But by an accident of geography and sociology, this neighborhood contained one of the largest concentrations of communists in New York City.

On the corner of Bronx Park East and Allerton Avenue stood the “Co-ops”—two buildings populated entirely by communists who had moved to the neighborhood as part of a cooperative housing experiment and had remained when the buildings reverted to private ownership. Filled with people for whom “activism was a way of life,” it was a formidable presence in the community. The Co-ops were “a little corner of socialism right in New York,” one activist recalled, “it had its own educational events, clubs for men and women, lectures, motion pictures.” But the rest of the neighborhood’s population, while not so militantly radical, came from comparable backgrounds to the Co-ops people. The majority were Eastern European Jews, skilled workers, and small businessmen who had accumulated enough income to move out of the [Lower] East Side and the South Bronx, but were hardly secure in their middle-class status. More important, many of them grew up in environments in which socialism and trade unionism provided models of heroism and moral conduct, and more than a few had extensive activist backgrounds, whether in bitter garment strikes in New York City or clandestine revolutionary struggle in Europe. Although relatively “privileged” compared to many New York workers (“Certain comrades…wanted to ridicule the movement,” one rent strike organizer wrote apologetically, “not realizing that these ‘better paid workers’ are members of the American Federation of Labor, many of them working in basic industries”), they suffered serious losses of income and employment and were not about to sink quietly into poverty and despair in response to the “invisible hand” of the market. When Unemployed Council activists began to organize them into tenant committees, they responded in a manner that perplexed and enraged landlords and city officials.1

In early January of 1932, the Upper Bronx Unemployed Council unveiled rent strikes at three large apartment buildings in Bronx Park East—1890 Unionport Road, 2302 Olinville Avenue, and 665 Allerton Avenue. In each of these buildings, the majority of the tenants agreed to withhold their rent and began picketing their buildings to demand 15 percent reductions in rent, an end to evictions, repairs in apartments, and recognition of the tenants’ committee as an official bargaining agent. In all three instances, landlords, moving quickly to dispossess leaders of the strike, argued that the demands were extortionate; judges readily granted them notices of eviction.2

But the first set of attempted evictions, at 2302 Olinville Avenue, set off a “rent riot” in which over four thousand people participated. As the city marshals and the police moved into position to evict seventeen tenants, a huge crowd, composed largely of residents of the Co-ops, gathered in a vacant lot next to the building to support the strikers, who were poised to resist from windows and the roof. When the marshals moved into the building and the first stick of furniture appeared on the street, the crowd charged the police and began pummeling them with fists, stones, and sticks, while the “non-combatants urged the belligerents to greater fury with anathemas for capitalism, the police and landlords.” The outnumbered police barely held their lines until reinforcements arrived. As the police once again moved to disperse the crowd, the strikers agreed to a compromise offer that called for two- to three-dollar reductions for each apartment and the return of evicted families to their apartments. “When news of the settlement reached the crowd,” the Bronx Home News reported, “they promptly began chanting the Internationale and waving copies of the Daily Worker as though they were banners of triumph.”3

At 665 Allerton Avenue, the attempted eviction of three tenants evoked disorders of nearly equal magnitude. The same elements all appeared: tenants barricading apartments and hurling objects at marshals and police; sympathetic crowds gathering and engaging police in hand-to-hand combat; the shouting of communist slogans and ethnic-political epithets (“Down with Mulrooney’s Cossacks”—an insult reserved for police—being the favorite). “The women were the most militant,” noted the New York Times. They constituted the majority of the crowds, the arrestees, and those engaged in physical conflict with the police. This time, the evictions did occur, but only with the help of over fifty mounted and foot police and a large and expensive crew of marshals and moving men.4

Bronx property owners moved quickly to try to contain the movement. At first, they tried arbitration. Following the evictions at 665 Allerton, landlords in Bronx Park East asked a blue ribbon committee of Bronx Jewish leaders to arbitrate the dispute, convinced that an impartial examination of the building’s books would show that the landlord could not meet the strikers’ demands without operating at a loss. But the strike leaders at 665 Allerton contemptuously rejected arbitration and indeed the whole notion that a “reasonable return” on one’s investment represented a basis for negotiation. “When times were good,” strike leader Max Kaimowitz declared, “the landlords didn’t offer to share their profits with us. The landlords made enough money off us when we had it. Now that we haven’t got it, the landlords must be satisfied with less.” Faced with this kind of bargaining position, landlords felt they had no choice but to pull out the stops to suppress the movement. By the second week of February 1932, two major organizations of Bronx landlords had formed rent strike committees that offered unlimited funding and legal support for any landlord facing a communist-led rent strike. Using the considerable political influence and legal expertise at their disposal, they developed a strategy that included “wholesale issuance of dispossess notices against striking tenants,” efforts to win injunctions against picketing in strikes, agreements by judges to waive normal delay periods in evictions, and efforts to ban rent strikes by legislative enactment. “The situation has become much graver than most persons suppose,” one landlord spokesman declared. “The strikes are spreading rapidly and scores of landlords are facing financial ruin or loss of their properties as a result of them.” Former state senator Benjamin Antin told landlords: “This is a peculiar neighborhood. It is the hot bed of Communism and radicalism. The people in this neighborhood are mostly Communists and Soviet sympathizers. They do not believe in our form of government.”5

The landlord mobilization broke the back of some of the strikes—mass evictions took place at 665 Allerton Avenue and 1890 Unionport Road—but it did not discourage communists from continuing rent strikes in Bronx Park East or spreading the movement to other neighborhoods. During January and February of 1932, communist-led strikes for rent reductions began breaking out in Brownsville, Williamsburg, and Borough Park (in Brooklyn), and in Crotona Park East, Morrisania, and Melrose in the Bronx. Like Bronx Park East, these were neighborhoods primarily inhabited by Eastern European Jews, possessed of a dense network of radical cultural and political organizations, but they were poorer, more troubled, and harder hit by the Depression. Irving Howe’s description of Crotona Park East, the neighborhood where the second wave of communist rent strikes attracted the greatest following, gives a sense of the grim atmosphere in which the party’s message was received:

The East Bronx…formed a thick tangle of streets crammed with Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, almost all of them poor. We lived in narrow, five-story tenements, wall flush against wall, and with slate covered stoops rising sharply in front. There was never enough space. The buildings, clenched into rows, looked down upon us like sentinels, and the apartments in the buildings were packed with relatives and children, many of them fugitives from unpaid rent. Those tenements had first gone up during the early years of the century, and if not so grimy as those of the Lower East Side in Manhattan or the Brownsville section of Brooklyn, they were bad enough.... Hardly a day passed but someone was moving in or out. Often you could see a family’s entire belongings: furniture, pots, bedding, a tricycle, piled upon the sidewalks because they had been dispossessed.6

In neighborhoods like these, communists’ appeals to strike invoked both indigenous traditions of militancy and a certain desperate practicality—since people were getting evicted anyway, why not put up a fight? Using the networks they possessed in fraternal organizations, women’s clubs, and left-wing trade unions, aided by younger comrades from the high schools and colleges, communists were able to mobilize formidable support for buildings that were on strike and to force police to empty out the station houses to carry out evictions. Nowhere was this more apparent than in the strike of five buildings on Longfellow Avenue between 174th and 175th streets, which the Greater New York Taxpayers Association made a test case of its efforts to suppress the movement.

Three separate waves of eviction provoked confrontations between police and neighborhood residents, the largest of which involved three thousand people “hurling stones, bottles and other missiles.” On another occasion, a mob of fifteen hundred fought the police for an hour and then took off after the landlord when they saw him moving through the crowd. The strike finally was broken, but only after more than forty evictions, an injunction against picketing, and numerous arrests and injuries. The police needed full-scale mobilization to suppress such strikes. “The police have set up a temporary police station outside one of the buildings,” read the Daily Worker description of a Brownsville rent strike. “Cops patrol the street all day. The entire territory is under semi-martial law. People are driven around the streets, off the corners, and away from the houses.”7

For rent strike organizers and sympathizers, and for landlords and city officials, the issues the strike evoked transcended housing and were not readily conducive to “rational” negotiation. For communists, rent strikes represented a way of arousing popular militancy and of recruiting people into the unemployed movement and the Communist Party. The party had no systematic analysis of housing issues and no legislative solution to the housing crisis; in the one theoretical article in the party press dealing with the rent strike movement, the emphasis was on “Building or organizations, on getting rent strikers ... to join our unions, to form shop committees ... to recruit them for the Party.” Although some strikes resulted in rent reductions for the tenants, many, if not most, resulted in eviction of some of the strikers.

Communists almost seemed to relish the confrontations resulting from evictions, regarding them as experiences that would radicalize the masses. Witness the rhetoric following the eviction of a rent striker on Seabury Place, in Crotona Park East: “A crowd of between 1,500 and 2,000 people witnessed the eviction of Zuckerman and his family.... Orators delivered blistering speeches from the fire escapes in denunciation of the policemen, the landlords, the marshal ... the capitalist system, the vested interests, and the imperialist designs of Japan in the Far East.” The Unemployed Councils had no coherent legal strategy to prevent evictions, or to argue the legitimacy of the rent strike before municipal judges—their major courtroom strategy appeared to consist of “intimidation by numbers.”8

Given the party’s disdain for legal niceties, its rejection of arbitration, and its open appeal for conflict between citizens and police, it is not surprising that municipal judges, city officials, and police, normally quite sympathetic to tenants in distress, regarded the communist rent strike movement as a pestilence to be stamped out. During the Longfellow Avenue protests, a municipal court judge warned striking tenants that “There are 18,000 policemen ready to keep order” and immediately issued dispossesses for all tenants who had withheld rent. Two weeks later, another judge granted an injunction restraining the picketing of Longfellow Avenue buildings. In the same strike, “the Mayor’s Committee, police, and city marshals... suspended their ordinary routine in evictions and [would] not withhold service of writs of eviction to investigate the neediness of the families.9

This fierce counterattack, for a time, appeared to put a damper on communist-led rent strikes. In May of 1932, the Real Estate News described the injunction against picketing as a “body blow” that “broke the Bronx rent strikes,” and events of the next six months appeared to bear out that claim. From May of 1932 to December of 1932, all articles on rent strikes in the Bronx Home News and the Daily Worker described disorders provoked by evictions rather than newly launched rent strikes—the landlords, not the strikers, appeared to have taken the offensive.10

However, in December of 1932 and January of 1933, the Unemployed Councils began a new wave of strikes that rapidly assumed far greater proportions than the last one. Beginning in Crotona Park East, the strikes spread into Brownsville, Williamsburg, Borough Park, the Lower East Side, and much of the East Bronx. In February of 1933, a panicked Real Estate News writer warned that, “There are more than 200 buildings in the Borough of the Bronx in which rent strikes are in progress, and a considerably greater number in which such disturbances are brewing or in contemplation.”11

The reappearance of massive rent strikes appeared to owe less to deteriorating housing conditions than to a strategic decision by communists to use the tactic as a component of a new campaign to mobilize the city’s unemployed. During the winter of 1932–1933, communist organizing among the unemployed expanded in breadth and effectiveness. Party leaders not only organized hunger marches on Washington, Albany, and City Hall, but initiated demonstrations and sit-ins at neighborhood relief bureaus that had been set up by the state to dispense direct relief to the unemployed. The simultaneous deterioration of employment prospects in the private sector, and a growing receptivity of public officials to providing aid to the unemployed, gave communists both a ready constituency and a target amenable to pressure. Party leaders responded by doing everything in their power to dramatize the hardship of the population and to stimulate mass action by the unemployed. Rent strikes had a proven capacity to inspire popular militancy, and the party urged its organizations of the unemployed and neighborhood cultural groups to make rent and eviction issues primary concerns.12

The campaign took hold first, and most strongly, in densely packed blocks of tenements at the southeast corner of Crotona Park (a neighborhood whose huge stretches of abandoned buildings made it a national symbol of urban decay in the 1970s). During December of 1932, rent strikes broke out on Franklin Avenue, Charlotte Street, Bryant Avenue, and Boston Road, all within five blocks of each other. Attempts by landlords to break the strikes with evictions produced street battles of epic proportions. “News of the impending eviction of the Lerner and Pzelsky families spread like wildfire,” wrote the Bronx Home News about a Franklin Avenue disorder:

Jeers and epithets were hurled at the police as they were jostled, shoved and manhandled.... A woman tenant appeared on a fire escape and screamed to the crowd to do something. This time, the efforts of Sergeant Maloney and his small force were unavailing. They were overrun, kicked, clawed and scratched. For more than an hour, the battle raged. Policemen were scratched, bitten, kicked and their uniforms torn. Many of the strike sympathizers received rough handling and displayed the scars of battle when order was again restored.

Evictions on Charlotte Street, occurring two weeks later, inspired a street battle with two thousand participants. The size of these protests reflected the movement’s unique ability to tap the energies and organizational skills of neighborhood women, who used networks developed in child rearing to mobilize the community and exploited the “myth of female fragility” to neutralize police attacks. “The women played a very big part in the rent strikes,” one Franklin Avenue tenant wrote. “When the police went for the men, the women rushed to protect them.... While the men were busy looking for work, the women were on the job.” “On the day of the evictions we would tell all the men to leave the building,” another activist recalled. “We knew that the police were rough and would beat them up. It was the women who remained in the apartments, in order to resist. We went out onto the fire escapes and spoke through bullhorns to the crowd gathered below.”13

By early January, strikes for rent reductions had broken out in an artists’ colony on the Lower East Side, in several tenements in Brownsville and Williamsburg, and in elevator apartment houses in Bronx Park East. Communist Party leaders now felt they had the nucleus of a citywide movement. “With demonstrations of 3,000 to 5,000 people,” wrote the Daily Worker:

with tenants of one house after another organizing, with block committees, unemployed council branches, workers clubs...uniting around tenant grievances, a hot fight against high rents and evictions is spreading through the working class sections of New York. Today is a high point in the struggle in the three main centers of conflict; the Bronx, the Avenue A section of Manhattan, and Williamsburg. The battle is on! Go this morning to the nearest picket line and put up a united front, mass struggle against the greedy landlords of New York.14

The party’s strategy of mobilizing its full network of organizations to picket rent-striking buildings and of organizing street rallies and protest marches through striking neighborhoods made the movement far more intimidating and effective than it had been the year before. “Yesterday, 1,500 people massed in front of 1433 Charlotte Street,” one account read, “preventing the eviction of eight tenants.... Speaking and picketing went on all day. There were 35 speakers from the Prospect Workers Club, Bronx Workers Club, the International Labor Defense, the International Workers Order, the Women’s Council, and the 170 Street Block Committee.” Although evictions did occasionally take place, many tenants won substantial reductions by striking and some won reductions merely by threatening to strike. In late January of 1933, the secretary of the Bronx Landlords Protective Association warned of “scores of landlords capitulating to demands of tenants threatening to strike” and claimed that landlords’ capacity to collect rent was being seriously impaired. “Rent strikes can be compared to epidemics,” he asserted, “for when a strike breaks out in one apartment house, strikes start in nearby houses or landlords are forced to capitulate to threats of tenants. Some landlords have been forced to reduce their rent a number of times.”15

Although several hundred buildings throughout the city may have been organized, the rent strike “epidemic” spread only to neighborhoods that had strong Communist Party organization. The majority of participants (using names of evicted tenants or arrested protesters as a guide) were Jewish, with some representation of Italians, Slavs, and Blacks. Irish-Americans, though composing a large percentage of the city’s working class, were almost entirely absent from the striking group (they tended to deal with tenant grievances through their local political clubs rather than through the left). Launched by communists as part of a comprehensive unemployment strategy, the strike had the aura of a communal revolt by Eastern European immigrants. In neighborhoods like Crotona Park East, evicted tenants were taken in by their neighbors until they could find new housing, and tenants opposed to the strike faced intimidation and harassment.

The expressive elements of the strike—the picketing, the marching, the songs sung and the slogans shouted—embodied the anxieties and hopes of people who had recently escaped an oppressive past and now faced the prospect of descent back into poverty. But despite the foreign accents and sectarian slogans, the movement had considerable force (“The entire East Bronx is full of fire,” one landlord lamented). Making a worse case analysis, landlords feared that the communal pressures at the strikers’ disposal would make it impossible to collect rent in large sections of the Bronx and thereby undermine the political and legal climate necessary to profitably operate rental property.16

By the last week of January 1933, the two major associations of Bronx landlords had developed a “concerted drive against rent strikes” which included “every legal device at their command.” It included some tested tactics—a central fund to pay the mortgages and legal expenses of landlords engaged in strikes; eviction of striking tenants; requests for injunctions against rent strike picketing. But it also included some new approaches—requests for “criminal conspiracy” indictments against rent strike leaders; circulation of a “red list” of tenants who had participated in rent strikes; and demands that the mayor’s office develop a coordinated program to suppress the strike. In approaching city officials, landlords emphasized the importance of “taking the streets away from the strikers,” since they believed that “picketing has always been the most important weapon of Communists in conducting rent strikes.”17

City officials and judges appeared to share this sense of urgency about the communist “rent revolt.” In late January, Mayor John O’Brien called a conference on the rent strike situation, which included the police commissioner and chief magistrate, representatives of the district attorney’s office, the office of corporation counsel, and savings banks and mortgage companies. Within the next two months, several actions followed that significantly increased the risks of participation in strikes. In mid-February, Magistrate William Klapp of the Bronx Supreme Court, holding two rent strikers on charges of “criminal conspiracy,” argued that they had “intimidated and threatened” tenants who were not ready to join in the strike. Two weeks later, Magistrate John McGoldrick of the Bronx Supreme Court granted an injunction restraining non-tenants from picketing a house that was on strike. Finally, in the last week of March, City Corporation Counsel Edward Hilly issued a ruling that the “picketing of apartment houses in rent strike demonstrations is unlawful” and conveyed to city police “authority for the arrest of such pickets.” This last action, based on the dubious ground that “there is no such thing known to law as a rent strike,” represented the most serious effort by the city’s law enforcement establishment to suppress the rent strike movement. Several days after it was issued, the counsel for the Bronx Landlords Protective Association claimed that the ruling “had such a sweeping effect that not a single rent strike is now in progress in the Bronx, although the borough seethed with such demonstrations before the circular was sent out.”18

Without question, the Hilly ruling put a damper on the rent strike movement. Sporadic strikes continued to occur—in the East Bronx, in Brownsville, in the Lower East Side—but the “epidemic” quality of the movement disappeared; arrests of pickets made the strikes more difficult and dangerous to carry out. However, the Unemployed Councils did not relinquish their drive to prevent evictions of tenants or to assure that rent levels were commensurate with incomes. Instead, they changed their target from the landlord to the home relief system. During the spring and summer of 1933, Unemployed Councils throughout the city began taking large numbers of tenants to the Home Relief Bureaus and having them sit in until they were given funds to pay rent. “In Williamsburg,” the May l9, 1933, Daily Worker claimed:

Half a dozen workers who refused to leave the Bureau ... forced the Home Relief Bureau to pay the rent in spite of previous repeated refusals. In Coney Island, over 30 families secured their rent by similar actions. In Manhattan and the Bronx, the Home Relief Bureaus were forced to revoke the “no rent” order in cases of workers participating in these militant actions.... In Harlem, struggles against the marshal and the restoring of workers furniture to their homes hastened...the payment of rent to Negro families.

Three weeks later, the Worker claimed, “Rent checks [were]...being issued to nearly 500 unemployed families in the Bronx by the Home Relief Bureau...as a direct result of picketing, demonstrations, and anti-eviction fights led by the Unemployed Councils.”19

The Unemployed Councils’ campaign to shift the onus of preventing evictions from individual landlords to the government proved a shrewd tactic. Stymied in their effort to sustain a massive rent revolt (partly by effective repression, partly because landlords could not profitably make concessions), party organizers found the city government amenable to collective pressure because of new funds made available by the Roosevelt administration and because of a political climate increasingly receptive to government aid to the unemployed. In June of 1933, Mayor O’Brien issued an order to city marshals instructing them to inform “the rent consultant of the home relief bureau” upon issuance of a dispossess and to give the bureau time to provide aid prior to the implementation of any eviction. In addition, if evictions did occur, marshals were ordered to guard tenants’ furniture until a representative of the home relief system arrived. The thrust of this action was to make the Home Relief Bureaus serve as a cushion for tenants who were behind in their rent, either by helping them remain in their apartments or by securing new quarters.20

O’Brien’s program, coupled with a gradual expansion of home relief funds and the implementation of New Deal work relief programs, rapidly eased the early Depression eviction crisis. Communist organizations of the unemployed still served as watchdogs for tenants with rent problems, but their actions increasingly took the form of advocacy at the relief system. Through the mid-Depression years, communist organizations of the unemployed still participated in eviction resistance, but rarely organized rent strikes. If tenants had difficulty paying their rent, Unemployed Councils (and later the Workers Alliance) took them to the relief bureaus, where they acquired semiofficial recognition as bargaining agents for the city’s poor, and persuaded relief officials to release sufficient funds to keep them in their apartments.21

The communist rent strike movement of the early 1930s must therefore be judged a qualified success, but in the sphere of income maintenance, not housing policy.

Communist organizers did not succeed in establishing the legitimacy of the rent strike, did not leave a viable legacy of courtroom strategy, and did not develop an effective campaign for legislation aiding low-income tenants. Their analysis of the economics of housing ranged from the primitive to the nonexistent. But they did give some unemployed tenants an opportunity to resist eviction from their homes and others a chance to dramatize a level of personal suffering that the mechanisms of the private housing market could not alleviate. Unable to offer “responsible solutions” to tenant problems, they helped force government into an income strategy that gave unemployed tenants a much-needed sense of security.

This is an excerpt from an essay which first appeared as a chapter in The Tenant Movement in New York City, 1904–1984, edited by Ronald Lawson (Rutgers University Press, 1986), and was titled “From eviction resistance to rent control: Tenant activism in the Great Depression.”

- Kim Chernin, In My Mother’s House: A Daughter’s Story (New York: Harper, 1984), 100–101; Interview with Sophie Saroff, Oral History of the American Left Collection, Tamiment Library; “The utopia we knew: The Coops,”Cultural Correspondence, Spring 1978, 95–97; “The political significance of rent strikes,” Party Organizer, February 1932, 23–24.

- Bronx Home News, January 10, 22, 1932; Daily Worker, January 5, 8, 1932.

- Bronx Home News, January 23, 1932; New York Times, January 23, 1932; Daily Worker, January 23, 1932; Interview with Sara Plotkin, January 23, 1976.

- Bronx Home News, January 28, 29, February 2, 1932; New York Times, January 30, February 2, 4, 1932; Daily Worker, January 26, February 2, 1932.

- Bronx Home News, January 31, February 3, 5, 7, 8, 1932; New York Times, February 10, 1932.

- Daily Worker, January 9, 18, 23, 28, 1932, Real Estate News, February 1932, 54–55; Kenneth Alan Waltzer, “The American Labor Party: Third Party politics in New Deal–Cold War New York, 1936–1954,” Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, 1977, 149, 153–154, 162; Irving Howe, A Margin of Hope: An Intellectual Autobiography (New York, 1983), 1–2.

- New York Times, February 27, March 13, 16, 1932; Real Estate News, March 1932, 90; Bronx Home News, February 12, March 16, 1932; Daily Worker, February 25, March 1, 8, 1932.

- “Political significance of rent strikes,” 23; Bronx Home News, June 8, 1932.

- Bronx Home News, March 10, 1932; New York Times, March 25, 1932; Real Estate News, April 1932, 134–135.

- Real Estate News, May 1932, 152; Bronx Home News, May 27, June 8, September 4, 10, 1932; Daily Worker, May 21, 30, June 1, September 10, 1932.

- Real Estate News, February 1933, 50.

- Mark Naison, Communists in Harlem During the Depression (New York: Grove Press, 1984), 76–78; Bronx Home News, November 27, 1932; Hunger Fighter, September 1932, 1–4; March 1933, 1–4.

- Daily Worker, December 7, 22, 1932, January 4, 6, 1933; Bronx Home News, December 7, 1932, January 5, 15, 1933; New York Times, December 7, 21, 1932, January 6, 17, 1933; Working Woman, March 1933, 15; Chernin, In My Mother’s House, 96–97.

- Working Woman, May 1933, 18; New York Times, January 12, 17 28, 31, 1933; Daily Worker, January 9, ii, 12, 14, 19, 1933.

- Daily Worker, January 9, 11, 20, 24, 28, 1933; Bronx Home News, January 25, 1933.

- On Irish–Jewish tension in New York see Ronald H. Bayor, Neighbors in Conflict: The Irish, Germans, Jews, and Italians of New York City, 1929–1941 (Baltimore: John Hopkins, 1978), esp. 87–108; Daily Worker, January 31, February 1, 4, 9, 11, 14, 15, 23 1933; Bronx Home News, February 1, 1933.

- Bronx Home News, January 15, 18, 25, February 15, March 26, 1933; Real Estate News, January 1933, 12–13, February 1933, 50–51, 59; New York Times, January 15, February 1, March 12, 1933.

- Bronx Home News, January 25, February 21, 24, March 9, 26, 1933; New York Times, March 31, 1933; Real Estate News, March 1933, 83; Brooklyn Eagle, March 27, 1933.

- Bronx Home News, Mar. 28, Apr. 11, June 1, 1933; New York Times, Mar. 28, June 1, 1933; Daily Worker, May 1, 11, 13, 18, 19, 31, June 3, 1933.

- New York Times, June 8, 1933; Real Estate News, June 1933, 164–165; Bronx Home News, June 8, 1933.

- Interview with Sophie Saroff; Frances Fox Piven, and Richard A Cloward, Poor People’s Movements: Why They Succeed, How They Fail (New York: Vintage, 1978), 76–82; Naison, Communists in Harlem during the Depression, 257–259.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Google+

Google+ Tumblr

Tumblr Digg

Digg Reddit

Reddit StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon