It can't happen here?

THE 2007–08 worldwide recession ignited revolutions that toppled long-standing tyrants in the Middle East and created the context for the first sustained fightbacks by workers in Europe in a generation. It also, more ominously, caused the reemergence of significant fascist movements in several countries, most notably Greece and France. In the first article of this two-part series, JOE ALLEN looks at the fascist threat in the United States in the late 1930s with an eye to what lessons can be learned to defeat the fascist threat today. It focuses primarily on the struggle against the Silver Shirts in Minneapolis, while part 2 will focus on the struggle against the German American Bund and the Christian Front in New York.

BY THE late 1930s, the combined forces of German and Italian fascism had scored a series of political and military victories that changed the balance of forces among the world’s major powers. Building on his successful occupation of Austria in April 1938, Hitler again triumphed five months later at the Munich conference—which permitted him to occupy the Sudetenland, the German-speaking region of Czechoslovakia. This was the beginning of his march toward the conquest of much of Europe.

Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, Hitler’s very junior partner, had previously overcome determined resistance and conquered Ethiopia in his quest to create a “new Roman Empire.” The only resistance to the forward march of fascism was the heroic defense of the Spanish Republic from the forces of fascist general Francisco Franco, but by the middle of 1938, the civil war in Spain turned in favor of the fascists with the extensive help of Germany and Italy.2

For many people, these fascist victories represented a darkening era. Others, however, were inspired by them. “Everywhere the fascists and their fellow travelers seemed to be riding high,” James Wechsler recalled in his autobiography, The Age of Suspicion. Wechsler was making a living as a journalist in New York, writing for the Nation magazine. He was a former student leader at Columbia University and had just recently left the Communist Party. In the not-too-distant future he would gain fame as longtime editor of the then-liberal New York Post. Weschsler was particularly concerned with the street violence of the New York supporters of the Michigan-based fascist priest Father Charles E. Coughlin.

In the United States Charles E. Coughlin was intoning his hymns of hate to growing multitudes and the echoes of his message were being heard on the sidewalks of New York.. . . Frankly emboldened by the Nazi successes, the Coughlinites for a brief period really appeared to be making headway in several neighborhoods; the street brawls, sluggings and anti-Semitic forays that we once stamped as strictly European were finally being enacted in our own country.3

This surge in fascist activity was not confined to New York City, then the most left-wing city in the United States and with the largest Jewish population in the world. All across the country, a variety of fascist and neofascist groups were crawling out from underneath their rocks, helped significantly by Coughlin’s work and his famously booming voice over the radio. Whether they were called the Silver Shirts, the German American Bund, the Christian Front, or the many split-offs from these, all were emboldened not only by fascist triumphs in Europe but also by a sharp turn to the right at home. “In the months since Munich and especially since the fall of Barcelona, and the definitive collapse of the New Deal policies, the fascist and semi-fascist movements in this country have been growing rapidly in numbers and boldness,” the newly founded Socialist Workers Party (SWP) declared at its founding convention in January 1938.4 This newly emboldened fascist movement, however, was met by growing and equally determined popular antifascist resistance.

The Silver Shirts

Minneapolis, Minnesota, from the turn of the nineteenth century until the mid-1930s was ruled by a ruthless business oligarchy known as the Citizens Alliance (CA). It successfully and boastfully kept the city free of any unions that could challenge their near complete domination of economic and political life. The first crack in the CA armor came with the election of Floyd Olson, the Farmer-Labor Party candidate, as governor in 1930. The popular Olson personified the shifting political landscape of Minnesota produced by the Great Depression. Reform was in the air, and the CA could feel power slipping from their hands. Olson also broke the unspoken ban on having Jews play important roles in the highest levels of state government. Teamsters Local 574, however, finally broke the CA’s stranglehold on Minneapolis through a series of militant, extremely well-organized strikes that rocked the trucking industry in the late spring and summer of 1934. Within a few short years, Minneapolis went from being the open shop capital of the United States to being one of its best-known union towns. Teamsters Local 574 (later known as Local 544) was led by a group of talented and experienced revolutionary socialists—who were first members of the Communist League of America and then the SWP—that included Swedish immigrant Carl Skoglund, a young Farrell Dobbs, and the Dunne brothers, Vincent, Miles, and Grant.5 The Dunne brothers especially elicited a visceral hatred from the bosses who literally growled at the mention of their names.6

The Minneapolis trucking strikes were a major event in the emergence of the militant industrial union movement of the 1930s and 1940s, and led to the organization of hundreds of thousands of truck drivers and warehouse workers. The success of the Minneapolis teamsters put wind in the sails of the entire labor movement across Minnesota and the Upper Midwest, a region still referred to at the time as the Northwest. Union organizers came from all over the country to learn their organizing techniques and strategies, including a young Jimmy Hoffa from Detroit. The CA and its supporters found themselves on the losing end of the battle for several years following the 1934 strikes. They rechristened themselves the Associated Industries (AI) in December 1936 and made several failed efforts to hem in the militant teamsters and their radical leaders but nothing worked. The Farmer-Labor Party also continued to dominate state politics even after the death of Olson in 1936 from stomach cancer. Olson’s elected successor, Elmer Benson, embraced even more left-wing policies and continued Olson’s policy of having Jews play a prominent role in state government and the Farmer-Labor Party. With the onset of the “Roosevelt Recession,” many of Minneapolis’s employers thought the ground had finally shifted in their favor, and some of them were quite willing to flirt with the fascist Silver Shirts to achieve their goals.7

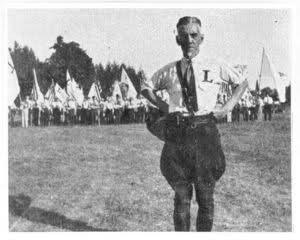

Modeling his organization after Hitler’s brown-shirted street fighters, William Dudley Pelley founded the Silver Legion of America, popularly known as the Silver Shirts, the day after Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany on January 30, 1933. Pelley was, in many ways, a typical American religious crackpot, but he became a violent anti-Semite and Nazi, inspired by the success of German Nazism. Pelley, himself, did not look like a menacing street fighter. With his graying hair, goatee, and pince-nez glasses, he looked like the aging choral director of a small Midwestern college. On formal occasions Pelley and his followers donned the official uniform of the Silver Shirts: navy blue trousers and black shoes. The distinctive silver shirt was emblazoned with a large scarlet “L” over the heart that added a slight varsity touch to the fascist-inspired uniform that stood for “Love, Loyalty and Liberty.”8

Pelley, while in uniform, tried to strike the image of an old-fashioned cavalry officer. Soon after he founded the Silver Shirts in 1933 from his Asheville, North Carolina, headquarters, the organization grew significantly and peaked at a membership of around 15,000. From his headquarters Pelley edited Liberation, the Silver Shirts’ national newspaper, and issued orders to his supporters across the country. The Silver Shirts drew support largely from struggling and retired middle-class businessmen and skilled workers in the Midwest and West Coast whose lives had been thrown into turmoil by the Great Depression. They came from overwhelmingly white Anglo-Saxon, German, northern European, and Protestant ancestry. There was also a large overlap in some areas between the Silver Shirts and the traditional far Right racist organizations like the Ku Klux Klan.9

The Silver Shirts’ menacing activities early on became the subject of congressional investigations. “Arms Plot Is Laid to San Diego Nazis” was the headline of the New York Times on August 8, 1934. Two marines, Virgil Hayes and Edward T. Grey, infiltrated the Silver Shirts at the behest of Marine Corps intelligence and revealed the “arms plot” to congressional investigators. Hayes testified before a congressional subcommittee in Los Angeles that the Silver Shirts had offered him money to purchase weapons stolen from military arsenals. When asked by the subcommittee investigator what the purpose of the Silver Shirts was, Hayes responded, “To change the government, William Dudley Pelley, the national organizer told me. . .. He also planned to deport the Jews.” The investigator then asked him if they advocated violence to take control of the government. Hayes answered, “Yes, I was commissioned as an instructor in military tactics with the Silver Shirts. I taught them the use of small arms and street fighting.”10

Grey testified about a Silver Shirt plan to capture San Diego City Hall by force:

It was planned for early in May [1934], when the Communists were to stage a May Day celebration. The Silver Shirts were ready, too. The 200 armed, trained Silver Shirts had orders to converge on the city from the outskirts. They counted on the Communists going in before them and taking the city by storm. Then, in the confusion, the Silver Shirts were to overthrow the Communists, their avowed enemies.11

The Silver Shirt “coup” failed because, according to Grey, the May Day demonstration was called off. How serious this plot was we will probably never know, yet the testimonies of the two marine infiltrators reveal an organization eager to obtain weapons, training, and the opportunity to seize power. There was no doubt that they were a dangerous organization to be on guard against. Pelley’s ambitions after 1934, however, were sidelined by the militant struggles of US workers, and the enactment of a series of historic social reforms by the Roosevelt administration that were embraced by a huge section of the population, including people that Pelley hoped to win to fascism. The Silver Shirts’ membership slumped, after peaking in 1934, while Pelley became ensnared in a legal case after allegations of stock fraud. Liberation was even forced to declare bankruptcy.12

Starting in 1936, Pelley attempted to revive his organizing efforts. He founded the Christian Party, which he hoped would funnel large numbers of men into the Silver Shirts, and ran for president.13 Pelley’s campaign battle cry was “Down with the Reds and out with the Jews.” The campaign was a flop in terms of votes but it gave Pelley a somewhat more legitimate platform from which to espouse his political views. It was in that same year that the Silver Shirts, according Minnesota historian Laura Weber, “first actively attempted to recruit members in the Twin Cities.” They found fertile ground. Minneapolis had a long history of anti-Semitism. “Its peak,” Weber argues, “occurred during the Great Depression.”14 A young, eager reporter, Arnold Sevareid, who would many years later become a fixture of CBS News as Eric Sevareid, penned the first major exposé of the Silver Shirts in Minnesota. Sevareid wrote in his autobiography Not So Wild a Dream:

Fresh from the theoretical battles of the classrooms, I was acutely concerned with the developing struggle in the country. When a couple of Communist acquaintances came to me with the information that a semisecret Fascist group, the Silver Shirt, were organizing widely in Minneapolis, I went to work.15

He went undercover for the Minneapolis Journal. Sevareid was a tall, lanky young man of Norwegian descent. He fit right in with the Silver Shirt crowd. Born in 1912 in Velva, North Dakota, his parents moved to Minneapolis when he was a teenager. He attended the University of Minnesota during a time of campus political ferment. He was an open admirer of Governor Olson and was radicalized by the 1934 teamster strikes. His series in the Minneapolis Journal was the first major exposé of the anti-Semitic fascist activity in the state and was something of a bombshell. “Anti-Semitism is the outstanding feature of the Silvershirts,” Sevareid wrote. He spent many “hair-raising evenings in the parlors of middle class citizens who worshipped a man named William Dudley Pelley, devoted to driving out the Jew from America.” They claimed a membership of 6,000 in the state. “They sang the praises of Adolf Hitler and longed for the day when Pelley should come to power as the Hitler of the United States.”16

“It was an unbelievably weird experience,” he recounted a decade later.17 At first Sevareid’s editor refused to believe him until he was able to gain admittance to a Silver Shirt meeting. His editor returned to the office and demanded: “Get me a drink, quick! God, I feel I’ve been through the fantastic nightmare of my life.” Sevareid “took them seriously, as a cadre of fascism, and we proposed to expose them in a series of articles.” Somehow it was leaked to a group of “liberal rabbis and wealthy Jews” that the Journal was about to publish Sevareid’s series, and the group asked the Journal to “withhold the story” fearing it would “abet a virulent form of anti-Semitism.” Their attitude, Sevareid thought, could be summed up as, “It would be better to ignore the madmen and pretend they didn’t exist.” Despite the opposition, his editor published the stories, “not as I wanted written, as a cry of alarm, but as a semi-humorous exposé of ridiculous crackpots who were befuddling otherwise upright citizens.”18 Nevertheless, after the first article appeared in print, the Minneapolis Journal sold several thousand extra copies above its regular distribution.19

What Sevareid wasn’t prepared for was the unrelenting hostility that he received from the good Christian, middle-class readers of the Journal. “I was threatened by telephone and letter every day to such a point that my family was alarmed for my safety and my brothers wanted to sleep, armed in my apartment.” He got no relief at work, “Odd characters, fuming and bridling, would march to my desk in the city room, and demand to know whether I was a Christian or a Bolshevik.” Self-righteous “lifelong subscribers” to the Journal would harass him on the phone, and when they didn’t get the response they desired, they called Sevareid’s publisher to complain about him and the Silver Shirts series. He was even denounced as a “Red” and “a foolish cub reporter” by the pastor of the biggest Baptist church in Minneapolis while he sat in the audience with his wife. Even his wife wasn’t very supportive. She turned to him and said, “After all, darling, you are a cub reporter, really.” Sevareid thought he was something of hero for the undercover reporting that he did, instead he was made to feel like an “ass.”20 It also demonstrated that a large pool of potential recruits existed for the Silver Shirts.

Political anti-Semitism

“A more violent threat to the Teamsters’ union was organizing secret councils in Minneapolis during the summer of 1938,” according to historian William Millikan. Millikan has written the only comprehensive history of the Minneapolis bosses’ four-decade war against organized labor. “The fascist Silver Shirts had returned to Minneapolis.”21 The Silver Shirt efforts benefitted greatly from an emerging split in the ranks of the Farmer-Labor Party (FLP). The sitting Minnesota governor Elmer Benson, who had been elected governor by the largest margin up until that point in the state’s history in 1936, was being challenged for the FLP nomination by longtime rival, Hjalmar Peterson. Peterson “obliquely” used anti-Semitism to attack Benson, according to Minnesota historian Hyman Berman, whose staff included a number of Jews appointed by Olson. Benson won the FLP nomination but what Peterson had begun was picked up on and, later, brazenly used in the fall election. The person who organized this was Ray P. Chase, “who was no lunatic-fringe anti-Semite, but was in the mainstream of Old Guard Minnesota Republicanism.”22 Chase’s “Research Bureau” was financed by some of the biggest names in Minnesota business including Jay C. Hormel of Hormel meatpacking fame and George K. Belden, president of AI.23 The stated goal of Chase’s bureau was “to block the efforts of the present Governor and his communistic Jewish advisors to perpetuate themselves in power, [and] to block efforts to initiate and promote the Soviet plan of the Social Ownership of Key Industries.”24

Pelley sent his top lieutenant Roy Zachary, officially designated by him a “Field Marshal” of the Silver Shirts, to Minneapolis. It was part of a three-and-a-half month, twenty-two state recruitment drive that he had methodically planned.25 Zachary, however, came to Minneapolis with a dark cloud hanging over his head. He was, at the time, under investigation by the Secret Service for allegedly threatening the life of President Franklin Roosevelt at a May rally of the Silver Shirts in Chicago. “If no one else will volunteer to assassinate Roosevelt, I’ll do it myself,” he allegedly bellowed to a Silver Shirt audience in May. Zachary was dogged by these “false charges,” as he called them.26 When he spoke in Tacoma, Washington, shortly after his Chicago stop, he complained that the CIO’s Timber Worker newspaper, “with a large circulation in the Northwest, published an account of my speech and repeated the false charge that I had threatened to assassinate the President.”27 When he spoke on July 18 in Spokane, Washington, Zachary was annoyed that “people attending our meeting in Redmens’ Hall had to pass through a street mob of several hundred Jews, communists and other radicals—sponsored by the League for Peace and Democracy—milling around the hall entrance with banners, blocking traffic, and otherwise demonstrating their determination to deny patriotic American citizens the right of free speech and peaceable assembly.”28 Zachary pressed on. He was determined to demonstrate to “the Silvershirts and other decent Americans throughout the nation. . .that our meetings and our program are being conducted as scheduled and in spite of opposition on the part of Jews and communists.”29

Hundreds of invitations were sent out by T.G. Wooster, state organizer of the Silver Shirts, to Minnesota businessmen and professionals calling on them to attend Zachary’s meeting in Minneapolis. Pelley wanted to recruit 3,000 to 5,000 new members to the Silver Shirts. This ambitious goal was to be done through a series of rallies at some of Minneapolis’s best-known venues as well as through private meetings.30 Pelley himself was expected to come to Minneapolis. The first two meetings were held on July 29 and August 2 at the Royal Arcanum Hall in Minneapolis. They were private meetings by invitation only. The invitation, in part, said:

You are hereby cordially invited to attend another meeting of patriotic, Christian citizens who believe there is a very urgent need for united action on behalf of our Government.

The Committee is pleased to announce that they were able to again secure the speaker [Roy Zachary] you heard on May 12th, who will return to our city for a one-night address, loaded with many new topics and additional information on relative alien forces that are seeking to undermine our government. . ..

Due to the growing interest in the movement it would be impossible to contact everyone in person as was done on the previous occasions. You are, therefore, requested to present this letter to the doorkeeper with an admittance fee of twenty-five cents. . ..

Any of your Christian, patriotic friends who desire to attend may accompany you and be admitted through this invitation.31

Among the many businessman and prominent political officials invited were Jay C. Hormel, George Belden, and Roy F. Dunn, the state secretary of the Republican Party. Zachary’s contact list also included such old right-wing warhorses as James F. Gould, the head of the American Committee of Minneapolis in 1919, an organization that dedicated itself to eradicating radicalism in Minnesota in the post–World War I era.32 If there is an obvious overlap between supporters of Chase’s Research Bureau and the mailing list of the local Silver Shirts, it doesn’t appear to be an accident. Chase carried on “a long time correspondence with William Dudley Pelley of the Silver Shirts. . .asking and receiving information regarding organizations and individuals.”33 His list of contacts also included A. C. Hubbard, president of the Mutual Truck Owners and Drivers Association, a company union affiliated with the AI, called Associated Independent Union (AIU).

The first meeting—on Friday night, July 29, at the Ark Temple—was the largest, drawing more than 350 people, including such “respectable people” as Dr. George Drake, a member of the Minneapolis School Board, and George K. Belden.34 Drake and Belden’s presence at a nasty fascist rally set off alarm bells for anyone concerned about the deteriorating political situation in the country and across the globe. (A more notorious example of an open show of fascist sympathy occurred the following day in Dearborn, Michigan, when the German government presented Henry Ford with the Grand Cross of the German Eagle, making him the first foreigner to receive such a medal from Hitler’s government.)35 According to the Minneapolis Labor Review, the official organ of the Minneapolis Central Labor Union Council, Roy Zachary called for “Vigilante bands to raid the headquarters of Drivers 544, declaring that the time for the ballot was passed and the only way to deal with the unions was to raid their headquarters and destroy them.”36

The Silver Shirts were declaring open war on Teamsters Local 544.37 Newspaper reporters and photographers were barred from the secret, invitation-only meeting but word had leaked out that the Silver Shirts were meeting in the city, and they gathered outside the Ark Temple. As their rally came to an end, the dispersing audience had their pictures taken outside the hall. “The threat of having their pictures taken,” according to the reporter for the American Jewish World, the weekly newspaper for the Twin Cities Jewish community, “is believed to be the reason for the small attendance of 65 at the next Tuesday meeting in the basement of the Royal Arcanum.”38 If this is true, it reveals something of the soft support for the Silver Shirts. Conspicuously, however, George Belden was once again in attendance. Roy Zachary violently attacked what he called the “Communist racketeers of the Teamsters’ Local 544.” Zachary claimed to the August 4 meeting that the Silver Shirts were “infiltrating” Minneapolis labor unions, including Local 544. Leaflets were handed out at both rallies inviting attendees to join the AIU’s Mutual Truck Owners and Drivers Association Local No. 1, whose primary target was Teamsters Local 544.39 At the end of both rallies, Silver Shirt guards attacked photographers. The American Jewish World reported that the photographers got the best of the Silver Shirts, especially after the second rally when “a fight followed during which a cameraman fell on his attackers with a blow to the chin.”40

Trotsky’s discussions with the SWP

How should the SWP leaders of Teamsters Local 544 respond to the Silver Shirts’ menacing threats as well as the general resurgence of fascist activity? The SWP’s thinking on this question was very much influenced by their discussions with the exiled Russian revolutionary leader Leon Trotsky in June 1938.41 Some of Trotsky’s most brilliant writings had been about the rise of fascism in Germany and how to combat it, but his voice had been silenced in the mainstream communist and socialist movements and was only heard by a handful of people. Many of the most experienced leaders of the SWP, including James P. Cannon, Ray Dunne, and Max Shachtman had been in Mexico throughout the spring and early summer of 1938 at Trotsky’s prison-like home in Coyoacan for extended discussions and formal meetings with him. He and his supporters from around the globe were engaged in preliminary steps to create the Fourth International, an attempt to form a rival to the Stalinist Communist International and the reformist Socialist International, and had produced a manifesto, The Transitional Program for Socialist Revolution.42 Most of their discussions revolved around how to implement the various parts of the Transitional Program, including how to respond to the resurgence of fascist activity in the United States.

Trotsky had recently read a book by an Italian worker published in France—a firsthand account of the brutal triumph of fascism in Italy. Trotsky wasn’t impressed by the author’s politics. “It is not his conclusions that are interesting but the facts which he presents.” For example:

He gives the picture of the Italian proletariat in 1920–21 especially. It was a powerful organization. They had 160 Socialist parliamentary deputies. They had more than one-third of the communities in their hands, the most important sections of Italy were in the hands of the Socialists, the center of the power of the workers. Then the author tells how they [the fascists] organized small bands under the guidance of officers and sent them in buses in every direction. In cities of ten thousand in the hands of the Socialists thirty organized men came into the town, burned up the municipality, burned the houses, shot the leaders, imposed on them the conditions of working for capitalists, then they went elsewhere and repeated the same in hundreds and hundreds of towns, one after another. With terrible terror and thus became bosses of Italy. They were a minority.43

In response to the fascist violence, the workers called a general strike and relied on their significant parliamentary presence to protect them from Mussolini’s violent movement but to no avail:

The fascists sent their buses and destroyed every local strike and with a small, organized minority wiped out the workers’ organizations. After this came elections and the workers under the terror elected the same number of deputies. They protested in parliament until it was dissolved. That is the difference between formal and actual power. All the deputies were sure that they would have power, yet this tremendous movement with its spirit of sacrifice was smashed, crushed, abolished by some ten thousand fascists, well-organized with a spirit of sacrifice, and good military leaders.44

Trotsky warned the SWP leaders not to be deceived by the small size or local character of the fascist organizations. “A fascist wave can spread in two or three years.”45 In Italy, and later Germany, the fascist movement went from a marginal political force to holding the reins of state power in just a few years. The aggressive, bold, gangster-like behavior of the fascist squads in Italy and Germany contrasted sharply with the anemic response of the leaders of the Italian Socialist Party and the German Social Democratic Party, still the major parties of their respective working classes. Trotsky recalled, “Hitler explains his success in his book. The Social Democracy was extremely powerful. To a meeting of the Social Democracy he sent a band with Rudolf Hess. He says that at the end of the meeting his thirty boys evicted all the workers and they were incapable of opposing them. Then he knew he would be victorious.”46

To defeat the fascists, Trotsky argued:

We must do what Hitler did except in reverse. Send forty or fifty men to dissolve the meeting. This has tremendous importance. The workers become steeled, fighting elements. They become trumpets. The petty bourgeoisie think these are serious people. Such a success! This has tremendous importance as so much of the populace is blind, backward, oppressed, they can only be aroused by success. We can only arouse the vanguard but this vanguard must then arouse the others.47

But these workers’ defense guards—be they armed with just their fists or clubs or more, depending on the character and scale of fascist violence—were not to engage in a simple one-to-one physical contest with the fascist squads. “Only armed workers’ detachments,” Trotsky insisted, “who feel the support of tens of millions of toilers behind them, can successfully prevail against the fascist bands. The struggle against fascism does not start in the liberal editorial office but in the factory—and ends in the street.”

The SWP/Teamsters Union leaders in Minneapolis were very skilled and experienced trade union leaders who had built a militant union through bruising strikes and confrontations with scabs and the auxiliaries of the Citizens Alliance. The union’s flying squads that were so effective in 1934 bore some of the features of the worker defense guard that Trotsky proposed. Still, Trotsky’s proposals were venturing into new and very controversial territory for them. They asked very simply: “How do we go about launching the defense groups practically?” Trotsky replied, “It is very simple. Do you have a picket line in a strike? When the strike is over we say we must defend our union by making this picket line permanent.”48 Trotsky’s use of “picket line” may not have been the clearest analogy at hand, or his belief that it would be a simple task revealed that he may not have understood the potential opposition to forming defense guards inside the trade union movement. With that possibly in the back of their minds, the SWP leaders asked Trotsky, “Does the party itself create the defense group with its own members?” Once again, Trotsky insisted:

The slogans of the party must be placed in quarters where we have sympathizers and workers who will defend us. But a party cannot create an independent defense organization. The task is to create such a body in the trade unions. We must have these groups of comrades with very good discipline, with good cautious leaders not easily provoked because such groups can be provoked easily. The main task for the next year would be to avoid conflicts and bloody clashes. We must reduce them to a minimum with a minority organization during strikes, during peaceful times. In order to prevent fascist meetings it is a question of the relationship of forces. We alone are not strong, but we can propose a united front. 49

Trotsky was optimistic. “In Minneapolis where we have very skilled powerful comrades we can begin and show the entire country.”50

Teamsters versus the Silver Shirts

Belden’s presence at the Silver Shirt rallies may never have been known to the wider population had it not been for the actions of Rabbi Albert Gordon of Adath Jeshurun Synagogue, one of the oldest and largest synagogues in Minneapolis, who first exposed him. “Thanks to Rabbi Gordon,” reported the Northwest Organizer, “the fact has become public that George K. Belden, head of AI, personally participated in meetings of the Silver Shirts, the fascist organization which is preparing to carry out armed raids on union halls.”51 The Northwest Organizer was the official weekly newspaper of Teamsters Joint Council but was largely the production of the staff of 544. Historian Alan Wald recalls his conversation about the paper with Farrell Dobbs, one of the most important SWP leaders in the Teamsters: “During the summer of 1934, [Herbert] Solow traveled to Minneapolis to edit the ORGANIZER.....Strike leader Farrell Dobbs...was listed as editor on the paper’s masthead, but it was initially Max Shachtman, and later Solow, who actually put the paper out and wrote most of the articles that appeared in it.”52

Gordon wrote a letter to the directors of Associated Industries asking for an explanation of Belden’s presence at the meeting, and then released the letters to the press.53 Whether Gordon had gotten his information from a sympathetic member of the audience or a spy who infiltrated the meetings is not clear. But what is clear is that Belden and the other AI executives were not happy about the public exposure of their seedy ties to the Silver Shirts. At first, AI took the position that Belden participated as an “individual,” not as a representative of their organization.

Belden then let it slip that he had attended a Silver Shirt meeting out of “curiosity.” A reporter from the Minnesota Leader, the weekly newspaper of the Farmer-Labor Association, now picked up where Rabbi Gordon had left off.54 The Northwest Organizer continued:

Under the skillful questioning of the interviewer it was revealed that not only had Belden attended the Silver Shirt meeting to which Rabbi Gordon called the attention of the public, but that he had also attended at least one other Silver Shirt meeting three months ago. Curiosity might have led him to one meeting, but once he saw what the organization was, why did he go to still other meetings? Why?

Why? For the simple reason that Belden found the Silver Shirts to his liking! Twist and turn as he might, that fact slipped through in the Leader interview. “They have some good things about (the Silver Shirts).” What things? Belden mentions one: “I am in sympathy with getting rid of the racketeers, employers and employees, whatever they are.”55

What were the reasons that motivated Belden and the AI, an extremely influential employers’ organization, to flirt with a relatively small fascist outfit like the Silver Shirts? The various “legal” methods employed by the Citizens’ Alliance and their successor Associated Industries had failed at curtailing the new and militant labor movement led by Teamsters Local 544. This situation was made worse by the deepening economic crisis in the country. “The economic crisis continues,” the Northwest Organizer declared,

and the Associated Industries ever more grimly attempts to shove the burden of the crisis onto the backs of the workers. Other methods not having succeeded, they now play with the idea of financing a gigantic organization of fascist gangsters to physically smash the labor movement. Some employers think that the Silver Shirts is that organization, and are already financing it heavily. Whether Belden had definitely made up his mind to throw in his lot with this particular fascist organization, is not the decisive point. The main point is: BELDEN IS PLANNING TO USE FASCIST THUGS AGAINST THE TRADE UNIONS.56

The Northwest Organizer made an appeal to the broad membership of the Minnesota labor movement that was at the same time a warning to the Silver Shirts:

On guard, brothers and sisters of the trade union movement! Guard well the portals of your unions against the fascist danger. Keep your eyes open everywhere for signs of the fascist storm troops. Prepare to deal with them as they deserve to be dealt with. Let every trade unionist say: “We shed our blood and gave our martyrs, to build our unions; we’ll fight to the death to keep our unions.”57

The leaders of the SWP and Teamsters Local 544 took the threats from the Silver Shirts seriously, but were the Silver Shirts’ threats real or just big talk? From the vantage point of the SWP leaders of Teamsters Local 544, the threats were very real and credible. A month earlier, the Northwest Organizer (June 30, 1938) reported that Ralph H. Pierce, a leader of the Associated Independent Union reported, “George K. Belden raised a pot of $35,000 to import gunmen to assassinate three leaders of Local 544.” Pierce first reported this to L. Boerbach, a painters’ union official, who then contacted the staff at Local 544 about the alleged murder plot. Pierce met with Grant and Vincent Dunne and Carl Skoglund on June 22. This plot was apparently too much for Pierce who broke with the other leaders of AIU, F. L. Taylor and E.T. Lee.

The murders were alleged to be committed the next day. Local 544 contacted the police who arrested Pierce but no others. The following day the police discovered a car near the Central Labor Union hall with two high-powered rifles with telescopic sights.58 Mickey Dunne also reported that around this time persons unknown were following him, and that he had seen strangers lurking near his garage. The events in Pierce and Dunne’s reports bore a strong similarity to the murder of Pat Corcoran, the secretary-treasurer of the Twin Cities Joint Council, on November 17, 1937. His murder remains unsolved to this very day. According to his grandson Doug Dooher, “A mobster hired by management interests. . .as he was closing the garage door [of his home], struck him on the side of the head, chased him into a neighbor’s yard, and shot him behind his right ear.”59

“This [the Silver Shirt threat] situation called for prompt countermeasures,” wrote Farrell Dobbs thirty-five years later. “So Local 544, acting with its customary decisiveness, answered the threat by organizing a union defense guard during August 1938.”60 The SWP wanted the union defense to be a broad formation.

Conceptually, the guard was not envisaged as the narrow formation of a single union. It was viewed rather as the nucleus around which to build the broadest possible united defense movement. It was expected that time and events could also make it possible to extend the united front to include the unemployed, minority peoples, youth—all potential victims of the fascists, vigilantes, or other reactionaries.61

They were very carefully following Trotsky’s advice. But they realized that they had to build a guard starting with Local 544, first. Ray Rainbolt, an organizer on the Local 544 staff and an SWP member, was elected commander of the force of six hundred union members. It was entirely made up of men. Rainbolt was an army veteran and was one of the few members of the SWP in Minneapolis who had military training.62 He was the right choice for the job. The Union Defense Guard (UDG) was divided into squads of five men each, each wearing “544 Union Defense Guard” armbands. Ideally, the UDG hoped it could mobilize at least 300 members once the call was put out, it took an hour to respond to any threat that required their services. Guard members drilled, and were educated, in Dobbs’s words, “on tactics used in the past by antilabor vigilantes and fascists abroad.”63 Many of the guard members were strike-tested rank-and-file members of Local 544, but that experience was augmented by many who were “former sharpshooters, machine gunners, tank operators. . .. Quite a few had been noncommissioned officers.”64 It was not a group that would frighten easily.

The UDG tried as much as possible to be an independent organization from Teamsters Local 544 and the SWP. It “raised its own funds—for purchases of equipment and to meet general expenses—by sponsoring dances and other social affairs.” It also made sure that “Members of the guard were not armed by the unions, since in the given circumstances that would have made them vulnerable to police frame-ups,” according to Dobbs. Only two .22-caliber pistols and two .22-caliber rifles were purchased by the UDG for target practice during its entire existence. If the Silver Shirts were to follow through on their threats and more firearms were needed to defend the Local 544 hall or the homes of the teamster leaders, then the UDG members were expected to rely on their own weapons. “Many of them had guns of their own at home,” recalled Dobbs, “which were used to hunt game; and those could quickly have been picked up if needed to fight off an armed attack by Silver Shirt thugs.”65

The requirements to join the UDG were few but important, and they included a willingness to defend all who may be potentially victimized by fascist groups and to take part in the minimal training required to have a reasonably well-organized guard. But in many ways the most important requirement was “acceptance of the democratic discipline required in a combat unit.”66 It was impossible for Silver Shirts and their supporters not to have been aware of the preparations of the teamsters and the SWP—the Northwest Organizer publicized the UDG’s activities for all to read. The September 8, 1938, edition front-page story was “544 Answers Fascist Thugs with Union Defense Guard.”67 It announced the guard’s purpose was the “defense of the union’s picket lines, union headquarters and members against anti-labor violence,” and expressed Local 544’s interest “in seeing other unions establish their own Defense Guards.”68

In mid-September, the Silver Shirts announced another recruiting rally for Minneapolis. This time, unlike the July and August rallies, it was to be addressed by William Dudley Pelley himself.69 Teamsters Local 544 was a popular union in Minneapolis. It had over 5,000 members and had many friends and allies among workers, radicalized students, and others who were impressed with their organizing abilities. It had many people who were willing to be their eyes and ears around the city. The UDG took advantage of this by setting up an informal intelligence network of people to keep an eye out for Pelley and other known Silver Shirt organizers. “On the day of the scheduled affair a cab driver delivered Pelley to a residence in the city’s silk-stocking district,” Dobbs recalled. “The driver immediately reported this to [Ray] Rainbolt, who telephoned the place and warned that Pelley would run into trouble if he went ahead. To show he was not bluffing, Rainbolt led a section of the union guard to Calhoun Hall, where the rally was to be held that night.”70 The audience fled into the night with the appearance of the UDG, and Pelley was a no-show. Later, another cab driver called Rainbolt and reported to him that he had dropped Pelley at the train station to catch a train to Chicago.71

This quick victory over the Silver Shirts was more like a skirmish between highly uneven forces, the well-organized UDG versus the bluster and posing Silver Shirts. It didn’t have the decisive quality of past battles that Local 544 had waged in the past, like the Battle of Deputies Run on May 22, 1934, when the striking teamsters destroyed the “special deputies” of the Citizens Alliance army, ending decades of tyrannical business rule in Minneapolis. Yet, it is important to recognize that the Silver Shirts never again attempted to hold rallies in Minneapolis. They held one last rally across the river in St. Paul on October 28, 1938, that was heavily guarded by the police. Roy Zachary was the main speaker, and he boasted: “Leaders of 544 have said we cannot hold meetings in Minneapolis, but we shall hold them, with the aid of the police. The police know that some day they’ll need our support and that’s why they’re supporting us now.”72

That day never came. In response to Zachary’s challenge, the UDG carried out one last mass mobilization when 300 members of the guard assembled in the center of Minneapolis in one hour for all to see. Dobbs sums it up well, “As for the ultra-rightists, they appeared to have gotten the union’s message loud and clear. Zachary made no further attempts to hold rallies in Minneapolis; fascist propaganda tapered off; and after a time it became evident that the Silver Shirt organizing drive in the city had been discontinued altogether.”73

Thanks to Ben Lassiter, Folko Mueller, Dave Riehle, Ben Smith, Patrick M. Quinn, and Alan Wald.

- The title of the article is taken from Sinclair Lewis’s novel It Can’t Happen Here, published in 1935 about a fascist takeover of the United States. A stage version of the book, cowritten by Lewis, premiered in October 1936 in twenty-one US theaters in seventeen states sponsored by the Federal Theater Project.

- The events described in this paragraph are found in most general histories of the Second World War. To understand the impact of the Munich conference on future events, see Telford Taylor’s Munich: The Price of Peace (New York: Vintage, 1979). For a contemporary Marxist view of the Munich conference see the “After Munich” issue of the New International, November 1938.

- James Wechsler, The Age of Suspicion (New York: Random House, 1953).

- George Breitman, ed., Founding of the Socialist Workers Party: Minutes and Resolutions 1938–39 (New York: Monad, 1982), 343.

- US Trotskyism operated under several official political labels in the 1930s reflecting the strategic orientation of the movement. It was first known as the Communist League of America until 1935 when it merged with A.J. Muste’s American Workers Party to form the Workers Party of the United States. From 1936 through the end of 1937, US Trotskyists entered and became the left wing of the Socialist Party. This was known as the “French Turn,” and they were known as the “Appeal Caucus.” Throughout the fall of 1937, supporters of the Trotskyists inside the Socialist Party were systematically expelled, and US Trotskyists formed their own stand-alone party, the Socialist Workers Party, during a founding convention from December 31, 1937, to January 3, 1938, in Chicago.

- The best account of the 1934 Minneapolis teamster strikes remains Farrell Dobbs’s Teamster Rebellion (New York: Pathfinder, 1972). There was a fourth Dunne brother, William, but he remained in the Stalinist Communist Party, and was actively hostile to his brothers' leadership of the 1934 Teamster strikes.

- For a wider lens on the background history of the Minneapolis teamsters strikes, the career of Floyd Olson, and the Citizens Alliance, see Charles Rumford Walker, American City: A Rank and File History of Minneapolis (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005) and William Millikan, A Union Against Unions: The Minneapolis Citizens Alliance and Its Fight Against Organized Labor, 1903–1947 (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2001). For Olson’s relationship to the Jewish community, see Hyman Berman, “Political Antisemitism in Minnesota,” Jewish Social Studies, Summer–Autumn 1976, 247–64.

- Arnold Sevareid, “The Silvershirts Meet Secretly Here but Come Out Openly in Pacific Coast Drive,” Minneapolis Journal, September 12, 1936, 1.

- Leo P. Ribuffo, The Old Christian Right (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1998) and Philip Jenkins, The Extreme Right in Pennsylvania 1925–1950 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2009).

- “Arms Plot Is Laid to San Diego Nazis,” New York Times, August 8, 1934.

- Ibid.

- “Silver Shirt Paper Fails,” New York Times, April 25, 1934.

- Membership in the Silver Shirts was confined to men but women could be members of the Christian Party.

- For a history of anti-Semitism in Minneapolis, see Laura E. Weber, “Gentiles Preferred: Minneapolis Jews and Employment 1920–1950,” Minnesota History, Spring 1991, 167–82.

- Eric Sevareid, Not So Wild a Dream (NSWAD) (Columbia, University of Missouri Press, 1995), 12. His five-part series began on September 11, 1936, and was run on the front page of the Minneapolis Journal.

- NSWAD, Sevareid, 69–70.

- Ibid., 69.

- Ibid., 70.

- Ibid., 71.

- Ibid., 71.

- Millikan, 336.

- Berman, 257. Peterson and his staff called prominent Jews in the FLP administration and party “Mexican Generals,” an odd yet apparent reference to the nationalist generals of the Mexican government in the 1930s. My interpretation is that it seems to imply “unelected radicals.”

- George K. Belden was one of the seventeen founding members of the Citizens Alliance, Millikan, 398n28. For an overview of Belden’s business and civic career see his obituaries in “G.K. Belden, Civic Leader Dies at 83,” Minneapolis Morning Tribune, May 21, 1953, and “George K. Belden, 83, Mill City Leader, Dies,” St. Paul Pioneer Press, May 21, 1953.

- Berman, 259.

- Roy Zachary, “Zachary Sees America, Greeting Silvershirts,” Liberation, August 7, 1938, 1, 2, 11.

- “U.S. Opens Probe of Silvershirts, Anti-Jew Legion,” Chicago Daily Tribune, May 23, 1938.

- Zachary, 11.

- Ibid., 11. The American League for Peace and Democracy was one of the largest mass membership political organizations initiated and controlled by the US Communist Party during the 1930s. Founded as the American League Against War and Fascism in September 1933, it claimed several million supporters across the country. In November 1937, it changed its name to the American League for Peace and Democracy. Its papers are archived at Swarthmore College, at http://www.swarthmore.edu/library/peace/....

- Ibid., 11.

- Millikan, 337.

- Wooster’s invitation is found in the Jewish Community Relations Council of Minnesota Records, Minnesota Historical Society.

- Millikan, 337. Berman, 258.

- Berman, 259. The files of the Jewish Community Relations Council of Minnesota Records at the Minnesota Historical Society contains a master list of potential supporters of the Silver Shirts and other fascist groups, one list of hundreds of names is called “Key List of Subversive Suspects.” How this list was compiled is unknown but likely included the infiltration of the Silver Shirt headquarters because two pages are marked “This list directly from Pelley’s files (1936?).”

- Millikan, 337.

- http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/nat....

- “Labor Hater Belden with Silver Shirts,” Minneapolis Labor Review, August 5, 1938.

- Zachary’s prejudices were an already established faith among the “respectable classes” in Minneapolis. Rev. George Mecklenburg, head pastor of the Wesley Methodist Church located in the then wealthy Lowry neighborhood of Minneapolis, held a virtually identical view. He had a weekly radio broadcast and column in the Wesley News. In his May 13, 1938, column called “Who Runs Minneapolis,” he wondered, “Some say 544 runs this city. I do not do know first hand what 544 does, but I do know that there is much government by threat and force in our city.” In the same column, he again wondered, “There are folks who say that the Jews run Minneapolis and they point out case after case where Jews are the owners of dives and places that violate the law.” See the Wesley News, May 13, 1938. Ray Dunne, a prominent SWP and Teamsters 544 organizer, debated Mecklenberg over charges of “labor racketeering” of Teamsters 544, See “V.R. Dunne Debates Rev. Mecklenberg; Defends Unions vs. Racketeering Charges,” Northwest Organizer, June 30, 1938.

- “Silver Shirts Are Organizing in Minnesota,” American Jewish World (AJW), August 5, 1938.

- Millikan, 337.

- AJW, 1.

- The SWP had previously discussed the fight against fascism at their founding convention in January 1938.

- Leon Trotsky, The Transitional Program for Socialist Revolution (TPSR), (New York: Pathfinder Press, 1973). For a contemporary account of the founding of the Fourth International, see Max Shachtman, “The Fourth International Congress,” New International, November 1938.

- “Completing the Program and Putting It to Work” (A discussion between Trotsky and unnamed leaders of the SWP) in TPSR, 139.

- Trotsky, 139.

- Ibid., 140.

- Ibid., 141. Trotsky says “Hitler explains his success in his book”—a probable reference to Mein Kampf.

- Ibid., 141. A survey of Mein Kampf doesn’t reveal this exact example that Trotsky refers too. Hess isn’t mentioned in Mein Kampf at all but there are many examples of Storm Trooper thuggery that are similar to the one Trotsky highlighted. Hitler refers to a “baptism of fire” for his Storm Troopers in November 1921 after members of the German Social Democratic Party (SPD) attempted to break up a Nazi meeting that Hitler was speaking at following the murder of prominent SPD supporters. A relatively small number of Storm Troopers fought off a much larger of number of socialists. See Mien Kampf, http://www.greatwar.nl/books/meinkampf/m..., chapter 7, 409–13.

- 48. Ibid., 140.

- 49. Ibid., 140.

- Ibid., 141. It is almost easy to miss when reading Trotsky’s discussions with the SWP leaders that they never directly name the fascist and Nazi groups in the US that they might be confronting. Not the Silver Shirts or the German American Bund or even semi-fascist groups like the Klan. It is a very one-sided conversation with Trotsky doing most of the talking. Trotsky also gets some important things wrong about US politics. He thought FDR would not run for a third term, and that Mayor Frank Hague, the boss of Jersery City, N.J., was a forerunner of fascism in the US. Hague was notorious for making such declarations as, “I am the law!” But he lost an important Supreme Court case pertaining to the rights of unions to organize in his city in 1940. Soon after he reconciled himself with the CIO and the national Democratic Party. Interestingly, Trotsky said he had read Jack London’s The Iron Heel, a fictional account of the rise of fascism in the US, and thought it “very interesting.”

- “Mr. Belden and the Silver Shirts,” Northwest Organizer (NWO), August 11, 1938.

- Alan Wald, The New York Intellectuals: The Rise and Decline of the Anti-Stalinist Left from the 1930s to the 1980s (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1987), 104.

- Millikan, 337.

- For a complete transcript of the Minnesota Leader interview with Belden, see “Attended Silver Shirt Meet,” Minnesota Leader, August 6, 1938.

- NWO, August 11, 1938.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- “Murder of 544 Men Planned, Is Charge,” NWO, June 30, 1938.

- Doug Dooher, “Who Killed Patrick Corcoran?” Minneapolis–St. Paul Magazine, August 1, 1998. Five months after Corcoran’s murder, Arnold Johnson, one of the local union’s organizing staff not affiliated with the SWP, was charged with the murder of Bill Brown, the president of the Teamsters Local 544, a close ally of the SWP. Brown had played a very public role in the victorious struggles of 1934 and was popular with the membership of the local. Many SWP leaders had a deep affection for Bill Brown. James P.Cannon, the national secretary of the SWP, recalled that Brown had a “big heart,” and his whole life revolved around the union. His death really unnerved people. Over 10,000 people attended Corcoran’s and Brown’s respective funerals. Johnson was later found not guilty of Brown’s murder. It should be remembered that the Communist Party, in one of its shabbier displays of slander and sectarianism, attempted to blame the SWP for the murder of Corcoran. See Carlos Hudson’s “A Frame-up that Failed” at http://www.marxists.org/history/etol/new...

- Farrell Dobbs, Teamster Politics (New York: Pathfinder, 1975), 141.

- Ibid., 142.

- Ibid., 142.

- Ibid., 143.

- Ibid., 143.

- Ibid., 143.

- Ibid., 142.

- “544 Answers Fascist Thugs with Union Defense Guard,” NWO, September 8, 1938.

- NWO, September 8, 1938.

- Millikan, 337–38.

- Dobbs, 144.

- Ibid., 144. I searched the mainstream press of the time hoping to find any reporting of these events but couldn’t find anything.

- Ibid., 144. A reporter from the Minnesota Labor Review infiltrated this Silver Shirt meeting and was roughed up by its guards. See “Silver Shirt Leader Poses—But Insists It’s Un-American,” Minneapolis Star, October 29, 1938.

- Ibid., 145. Pelley told his demoralized supporters to support the Republican Harold Stassen in the coming election. He declared, “If it can’t be done with ballots, now, there must be bullets later.” Pelley’s letter in the files of the Jewish Community Relations Council of Minnesota Records, Minnesota Historical Society. George Belden and T.G. Wooster of the Silver Shirts were photographed together in late October. Wooster publicly endorsed Stassen for Governor. See “Backing Stassen, Silver Shirt Chief tells Leader reporter,” Minnesota Leader, October 22, 1938.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Google+

Google+ Tumblr

Tumblr Digg

Digg Reddit

Reddit StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon