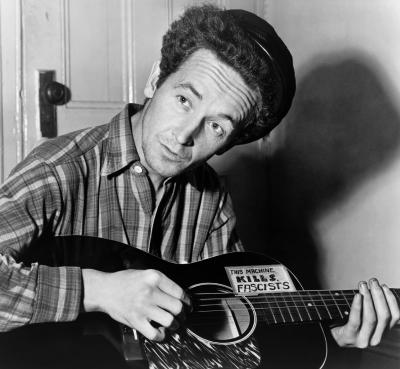

Woody Guthrie: "Songs that prove to you this is your world"

ON JANUARY 19, 2009, a crowd of thousands gathered in front of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. It was the day before the inauguration of Barack Obama as president of the United States, a country where it had once been perfectly legal to own someone with Black skin. The historic symbolism of gathering in front of the Lincoln Memorial, where Martin Luther King Jr. had given his “I Have a Dream” speech, was palpable.

There, living folk legend Pete Seeger, along with Bruce Springsteen and Seeger’s grandson, Tao, backed by a multiracial choir led the large crowd in a celebratory sing-along. Their song of choice? “This Land Is Your Land” by Woody Guthrie.

Few musicians or songwriters have had as massive an impact on American music as Woody Guthrie. “This Land Is Your Land” is one of the best-known songs in US history—even among those who know nothing else of Guthrie’s works. It’s been featured over the years in commercials for Coca-Cola and American Airlines, and performed on floats at the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade. Conversely, it’s also filled the air at union rallies, antiwar demonstrations, and, most recently, actions of the Occupy movement.

This year, there are countless concerts, performances, and other events being planned to celebrate what would have been Guthrie’s one hundredth birthday. These events and more are welcome. Guthrie’s legacy is well worth celebrating. But perhaps because of the sheer omnipresence of his influence, there persists a nebulous, “all things to all people” atmosphere surrounding the songwriter’s work.

As always, it’s a lot more complex than that. While Guthrie, the myth, may be easily manipulated and used, there’s a good chance that Guthrie, the man, might balk at his music being used to sell soda. After all, this was an artist who once passionately declared his outright hatred for what capitalism does to music:

I could hire out to the other side, the big money side, and get several dollars every week just to quit singing my own songs and to sing the kind that knock you down farther...the ones that make you think you’ve not got any sense at all. But I decided a long time ago that I’d starve to death before I’d sing any such songs as that.

Recent years have also seen discoveries surrounding the “original” or “lost” verses of “This Land” that show its content to be less of a celebratory missive than a bold reminder of American inequality. This is on top of scholarship seeking to bring Guthrie’s radicalism back to the center of an appreciation of his art, including the recent Woody Guthrie, American Radical by University of Central Lancashire professor Will Kaufman.

The sanitizing of Guthrie is nothing alien to the music business; anyone familiar with the real legacies of John Lennon, Bob Marley, and so many others will recognize this process. Rebellion might be dangerous, but it’s also cool. And if a musician’s radicalism can be hewn from their artistic greatness, then the bucks roll in unencumbered. What’s more, Guthrie’s career coincided with and was a crucial component in the formation of American popular music. Stripping his music of its subversive content means doing the same for a key link in American history.

The problem is that ultimately the shape of an artist’s work can’t be separated from the time in which it was made. This is especially true for Woody Guthrie, which might explain why his radical core inexorably resurfaces time and again, despite efforts to bury it once and for all. Explaining his music and contradictions means delving into the rich yet hidden history of American class struggle.

The Do-Re-Mi

In his autobiography Bound for Glory, Guthrie would claim that his activism began at an early age. But then, in true folk music fashion, he was often given to embellishment. In fact, Guthrie’s beginnings could not have appeared further from that of a radical.

Born July 14, 1912, in Okemah, Oklahoma, Woodrow Wilson Guthrie was named after then-governor of New Jersey and soon-to-be-president Woodrow Wilson. Guthrie’s father Charles was an aspiring real estate developer and local Democratic politician with a strong racist and antisocialist streak. Charles would frequently rail in speeches and newspaper op-eds against the “moral depravity” of the Socialist Party.

Years later, the younger Guthrie would discover that his father was present at a notorious Okemah lynching the year before Woody’s birth. He also speculated that his father was a member of the Ku Klux Klan.

Well into his adulthood Woody clung to establishment ideas. By the time he had reached his twenties, however, the Great Depression had taken hold. Making matters worse was the “Dust Bowl” in the American farmlands—along with drought, disease, crop failures, and farm foreclosures.

The Guthries, who had always possessed strong middle-class pretensions, weren’t farmers. Nonetheless, they were literally scattered to the four winds by poverty like so many other families in their area. Woody was one among the thousands of “Okie” migrants who went west searching for some form of living. At that time, he believed his ticket out of poverty was to make it big as a cowboy singer in the vein of Will Rogers.

The journey to California—a stark and destitute reality contrasted to the “land of plenty” that was supposed to be at the other end—changed all that. When Guthrie and his cousin “Oklahoma” Jack knocked on the door of Los Angeles’s KFVD radio station in 1937, he had little to his name aside from the guitar on his back. One of the songs that Woody performed for their audition that day has since become one of his best known: “If You Ain’t Got the Do-Re-Mi.” According to Will Kaufman:

“If You Ain’t Got the Do-Re-Mi” [was] about an illegal blockade that had been set up by the Los Angeles Police Department, hundreds of miles outside their jurisdiction, to prevent the Dust Bowl migrants from entering the state of California unless they had fifty dollars or more to prove that they weren’t “unemployable.” The blockade had only lasted for a few months in 1936—it was gone by the time Guthrie arrived in California—but the memory of the insult was fresh enough to provoke a stinging musical critique. It was fairly strong stuff for someone who simply wanted to sing cowboy music and make a few bucks.

This “strong stuff” did indeed stand apart from the lion’s share of mainstream music. Record companies’ general interest was in smooth, prepackaged (and overwhelmingly white) crooners like Perry Como and Bing Crosby. Blues was shoved into the category of “race records,” along with all but the most accessible big-band jazz. What is now broadly called folk and country was demeaned “hillbilly music.”

Folk and country were seen as appealing to niche markets, those most marginalized in society and deemed somehow unimportant. Even KFVD, whose primary musical programming was “cowboy music,” was taking a risk by broadcasting an artist as coarse, unpolished, and brash as Guthrie. But the station’s owner Frank Burke was a leftist; he had been a supporter of Upton Sinclair’s End Poverty in California campaign. This surely had a lot to do with his agreement to hire Guthrie.

Another risky hire for Burke and KFVD was Ed Robbin, member of the Communist Party (CP) and local correspondent for the party’s West Coast newspaper, People’s World. Burke had given Robbin a spot three times a week at KFVD. One day in 1938, Guthrie approached Robbin about listening in on his show. Robbin agreed, and it was there that he was pleasantly surprised to hear Guthrie perform a song about Bay Area former labor leader Tom Mooney.

Mooney had been convicted of involvement in the San Francisco Preparedness Day parade bombing in 1916. His conviction was rightfully considered by labor activists to have been little more than the result of a show trial. In 1938, after over twenty years of campaigning among radical groups, California’s newly elected governor Culbert Olsen finally pardoned Mooney and had him released.

Mooney had recently been interviewed on KFVD. But Robbin was unaware that Guthrie—who was now hosting his show by himself—had any political streak whatsoever. By his own admission, his jaw hit the floor when he heard Guthrie perform “Mr. Tom Mooney Is Free” on the air. Not only that, but Guthrie had closed the song urging his listeners to tune into Robbin’s commentaries: “He tells the truth, and that’s pretty rare in this town.”

Robbin was stunned. Later that day he requested the songwriter perform at an indoor rally the CP was holding in Mooney’s honor the next evening. Guthrie was happy to oblige, and after some prodding, so were the rally’s organizers.

The thousands in attendance that night were as enthralled with Guthrie as Robbin had been. According to Guthrie’s biographer Joe Klein in Woody Guthrie: A Life,

The audience went wild over the last verse of the Tom Mooney song, where Woody suggested that the thing to do now was to free the rest of California. They wanted to hear more. So, while tuning his guitar between songs, Woody told a few stories about the goons and vigilantes he’d met on the road and then swung into one of his songs about the dust bowl refugees. He received another hooting, stomping ovation, and decided to sing another song. He’d never experienced anything like this before . . . and they obviously hadn’t seen anything like him either. It was love at first sight.

Guthrie had encountered many CP members in his travels; they were the most dedicated union organizers among migrant laborers and field workers. The Mooney rally had been his first official Communist Party event, though. Not long afterward, Ed Robbin became his booking agent, and he was quickly confirmed to play at picket lines and union halls around California. He also began writing his famed “Woody Sez” column for the Daily Worker. Guthrie had decisively stepped into the fray of the American Communist movement.

The CP in 1938 was a tragic contradiction. Though its members had played often heroic roles in myriad strikes, antiracist struggles, and international solidarity campaigns, it was by the 1930s completely “Stalinized.” The 1917 Russian Revolution had cracked under the weight of civil war and international isolation; its working class was a shambles and the country had fallen into hands of a bureaucratic apparatus led by Joseph Stalin.

The CP, like all official Communist parties, had its line increasingly determined not by the aim of workers’ revolution but by the foreign policy needs of Moscow. In 1936, the party began effectively lending its support to a “Popular Front” with the Democratic Party as the lesser of two evils, and in some cases became President Franklin Roosevelt’s most enthusiastic cheerleader.

Nonetheless, the party’s commitment to grassroots struggle and a workers’ world (at least in its rhetoric) was what inspired over a million people to pass through its ranks during the Depression. Countless others, including Guthrie, would never join but would remain sympathetic—sometimes for their entire lives.

Contrary to what some might think, Guthrie was neither rash nor disingenuous in his political loyalty. Both Klein and Kaufman spend a good deal of time in their respective books mentioning the books that Guthrie digested during his political life, for instance veteran labor activist and leading CP member Ella Reeve “Mother” Bloor’s autobiography We Are Many (whose experiences organizing miners provided the source material for Guthrie’s “Ludlow Massacre”) and William Z. Foster’s Pages from a Worker’s Life. Years later, Guthrie’s copy of Marx’s Capital was discovered with notes such as “must memorize contents” written in the margins.Years later, in a letter to his sometime collaborator and wife Marjorie Mazia, he would write:

The big rich landlords, gambling lords, rulers and owners are cussing the Communists loud and long these days. The Communists always have been the hardest fighters for the trade unions, good wages, short hours, nursery schools, cleaner workshops and the equal rights of every person of every color. Communists have the only answer to the whole mess. That is, we all ought to own and run every mine, factory, timber track . . .

The end picture is clear. Guthrie, far from being some naive Okie manipulated by cosmopolitan leftists, was a profoundly intelligent and sensitive individual who believed one hundred percent in a world run by working people. This isn’t to say that he didn’t make some truly boneheaded judgments in his defense of the CP. Most notorious was using his radio show to speak (sing, actually) in favor of the nonaggression pact between the Soviet Union and Hitler’s Germany in August 1939. Plenty of sympathizers cut ties with the CP for Stalin’s alliance with the fascist enemy; Guthrie wasn’t one of them. For his boss Frank Burke, this was one step too far. Guthrie and Robbin were both fired from KFVD.

Hard-hitting songs

Not long before Guthrie came around, the Communist Party’s views on music had been, at best, out-of-date. The Pierre Degeyter Society, a Communist-affiliated musical club with chapters on campuses across the United States, promoted the idea that music in a socialist society would be little more than workers composing classical operas. Stalinism’s heavy emphasis on stuffy, formalized art for the use of propaganda (laughably called “socialist realism”) certainly didn’t help matters.

The arrival of Guthrie, however, coincided with an influx of folk, blues, and jazz artists into the party’s orbit. Bebop innovators like Max Roach and Dizzy Gillespie were playing CP-sponsored dance parties. Lead Belly was being invited to play his “Bourgeois Blues” at Communist summer camps. And a large crop of radical and progressive folk singers—Josh White, Aunt Molly Jackson, Sarah Ogan—followed with him.

Accompanying all this was a broader shift in music. Slowly but surely, the Perry Comos and Bing Crosbys of the world were being supplanted on the radio in favor of a more grassroots sensibility. Musician Mat Callahan, in his book The Trouble with Music, explains that the late 1930s were a time when “popular culture” had not only taken shape but assumed a position of dominance in the West:

Not only was bourgeois art knocked off its pedestal but the global struggle for revolution elevated the popular arts above it.... Some of the greatest popular music and literature was made during this period, quintessentially American and yet proletarian and internationalist. Paul Robeson, Woody Guthrie, Billie Holiday, Pete Seeger, Leadbelly, Duke Ellington—the list is endless and it is most enlightening. The body and soul of what America purveys to the world as its legacy was made by artists whose work was dedicated to the “popular” in the artistic sense, to the People as a political category, and against racism, fascism, imperialism and war.

No more was music just the creation of some slick, uniquely gifted individuals with the backing of music industry honchos. Now, any working person could pick up a guitar or a harmonica and have their story taken seriously. What had previously been dismissed as “race” or “hillbilly” music was increasingly accepted as more credible and authentic. When Guthrie moved to New York City in 1939, this shift was in full swing.

Surrounding him was a throng of activists and musicians profoundly inspired by the emergence of a radical working-class folk culture. Pete Seeger, Josh White, Millard Lampell, Bess Lomax (sister of folk musicologist Alan Lomax, one of the earliest to record Guthrie’s songs), Sonny Terry, and Brownie McGhee.

It seemed only logical that they coalesce in some way, and in 1940, the Almanac Singers came into being. They weren’t so much a band as a confederation; membership was always changing depending on individual artists’ other commitments. Guthrie, while not always the most reliable, was certainly a powerful influence on the group. Looking at the tour schedule for the Almanacs, one gets the sense that they’re peeking at Eugene Debs’s day planner. They performed not just in New York but also across the country, at fundraisers for the People’s World and the American Peace Movement, and picket lines for striking gypsum miners and autoworkers alike.

This was a time of ascendancy for the American labor movement—in particular the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). Since splitting from the American Federation of Labor (AFL) five years previously, the CIO had surpassed the AFL in both size and militancy. In contrast to the AFL’s concessions to segregation, the CIO put a premium on fighting racism both on the shop floor and, often, in the world at large too. The same was true for many other unions outside the CIO’s direct sphere of influence, particularly in the American South.

This put union organizers—which included a great many CP members and sympathizers—squarely in the crosshairs of American racism. One such organizer was Annie Mae Merriweather, an African American woman from Lowndes County, Alabama, active in organizing sharecroppers. After the suppression of a 1935 strike, antiunion thugs Vaughn Ryles and Ralph McGuire shot and killed her husband and fellow organizer, Jim Press. They then kidnapped her, hung her by her wrists in a nearby barn, whipped and sexually assaulted her, then left her for dead. She survived and later told her story to the NAACP.

Guthrie had heard Merriweather’s story before. It had become one of the most widely known of the Southern sharecroppers’ struggle—not just for its gruesome details but for the iron resolve that Merriweather displayed both during and after. After playing an engagement for Oklahoma City oil workers in May of 1940, local CP organizer Ina Wood asked Guthrie and Pete Seeger “isn’t it about time you wrote a union song for women?” They worked late into the night, and set Anna Mae Merriweather’s story to the deceptively upbeat tune of the “Redwing” polka:

This bloody crime was done

Out where the buffalo run

By old Bob Ryles [sic]

And Ralph McQuire [sic]

With a knotty rope

They soaked in blood

As this union girl they beat

[They] Said “I want naked meat”

They swung her up from a rafter there

For saying what she said:

“You have robbed my family and my people

My Holy Bible says we are equal

Your money is the root of all our evil

I know the poor man will win this world”

Though the graphic nature and particular references were later toned down, this was an early version of what has since become a labor standard: “Union Maid.” It was included in the Almanacs’ second album Talking Union, released in the early summer of 1941.

Guthrie’s output generally followed this theme during these years—as he called it in the folk song compendium he compiled with Seeger and Alan Lomax, “hard hitting songs for hard hit people.” Stories of ordinary people trampled under the system’s boot figuring out how to retain their dignity and hit back. His recording sessions included songs like “Tom Joad,” his two-part adaptation of John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath; parables of modern-day Robin Hoods like bank robber Pretty Boy Floyd; and “Blowin’ Down This Old Dusty Road” with its quiet declaration “I ain’t gonna be treated this way.” He even retold the story of Jesus Christ as a man cut down by the Romans for daring to demand the rich give their money to the poor:

When Jesus come to town, all the working folks around

Believed what he did say

But the bankers and the preachers, they nailed him on the cross,

And they laid Jesus Christ in his grave

Given the heady and often desperate times in which they were released, there can be little doubt that the overarching message of these songs was as powerful as it was radical.

Whose land?

Guthrie and the Almanacs’ rise to prominence didn’t go unopposed. Several right-wing critics bemoaned the fact that self-declared Communists were becoming accepted in the mainstream. Carl J. Friederich, a Harvard law professor, wrote for The Atlantic magazine that the Almanacs’ song “For John Doe” in particular was “strictly subversive and illegal.” To Friederich, folk music generally was a “poison in our system” whose relative ease in spreading made it an especially pernicious threat to the American way of life.

Such criticisms, shrill as they were, weren’t entirely off base. Guthrie’s songs deliberately bucked the trend of Hollywood and Broadway’s sunshiny show tunes and Tin Pan Alley’s sanitized parlor ditties. Lyrics like those of “Union Maid” reveal just how serious he was about his role in this task. Guthrie seemed to have little tolerance for culture that attempted to sugarcoat the hard daily reality for poor and working people. And so, when he heard Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America” choking the radio waves during his travels, something about the song obviously stuck in his craw. It was February 1940, and he set to work on writing an antidote:

One bright sunny morning in the shadow of the steeple

By the relief office, I saw my people—

As they stood there hungry

I stood there wondering if

God blessed America for me

Why Guthrie shelved these lyrics for almost five years isn’t clear. It’s likely that to him it was just another idea that hadn’t yet congealed. It is worth pondering, however, whether the CP’s attitude toward World War II had anything to do with it. After Hitler broke the nonaggression pact and invaded the Soviet Union, the Communist Party performed yet another about-face and became the most gung ho supporters of the American war effort. The party even went so far as to support a nationwide “no-strike pledge” and the internment of Japanese Americans.

Once again, Guthrie stayed the course on the CP’s line. He did three tours with the Merchant Marines and served in the US Army, though he was considerably hard to handle while being stationed at the barracks. His recording and performances were sporadic during these years. When he did manage to perform, his pro-union, antiracist, working-class militant material took a backseat to flag waving and militarism. Even many of his antiwar songs, often brilliantly bitter in their condemnation of Roosevelt’s saber rattling, were retooled into frightening pro-war missives. It’s easy to see how questioning whether God did indeed “bless America” would be off limits in the midst of all this.

“This Land Is Your Land” would eventually be recorded in 1944 between his military stints, and wouldn’t be released until a few years later. By that time, it appeared the pendulum had swung back. The year 1946 saw the biggest strike wave in American history, including the general strike in Oakland. The CIO launched “Operation Dixie,” an attempt to unionize the South and strike a blow against Jim Crow segregation in the process. The struggle for civil rights also appeared to be reemerging into American politics. When Isaac Woodard, a Black army veteran who had been honorably discharged mere hours before, was brutalized and permanently blinded by Batesville, South Carolina, police in February 1946, it produced a national outcry.

Guthrie, like many other CP members and socialists, threw himself headlong back into the unfinished business of American class struggle. His work reflected it too. He, along with writer Irwin Silber, Seeger, and others, formed the People’s Songs collective—a short-lived and more loose-knit attempt at continuing the Almanacs’ work—in 1946. He wrote reams of songs showcasing America’s radical labor heritage, including an entire album’s worth of material dedicated to executed anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti.

In August, he played in front of an audience of over 30,000 at a rally for Woodard in New York’s Lewisohn Stadium. The bill also included such celebrities as Cab Calloway, Orson Welles, Milton Berle, and Billie Holiday. Guthrie wrote a pair of songs dedicated to the “Trenton Six,” Black men convicted of killing a white man in New Jersey on shoddy evidence in 1948.

The apparent revitalization of radical and antiracist activism was short-lived, however. In fact, one of America’s most reactionary periods was only right around the corner. For Guthrie, much of this could be summed up in one word: Peekskill.

Fascism on the Hudson

On August 27, 1949, People’s Songs organized an outdoor benefit concert for the Civil Rights Congress featuring Guthrie, Seeger, Paul Robeson, and a collection of other progressive musicians not far from the town of Peekskill, New York. Before all of the artists had arrived, it was apparent that the show was in trouble. A growing mob of racists had congregated nearby, first lynching an effigy of Robeson, then beating thirteen people headed for the picnic grounds. They shouted slurs such as “commies,” “kikes,” and “niggers,” and burned a cross on a nearby hill. Members of the local Ku Klux Klan (KKK) had mobilized, and were also so confident that they appeared in public without their robes or hoods!

Police were called, but didn’t arrive until hours later, and even then refused to intervene. The local American Legion post, which along with the KKK had been instrumental in organizing the mob, claimed no involvement, and no real investigation was ever performed into their actions that day. In the aftermath, the local Klan reportedly received over 700 requests for membership in the Peekskill area.

The horrifying violence of August 27 made holding the concert impossible. Unionists and radicals in the area organized a protest campaign, and the show was rescheduled for a week later on September 4 at an old golf course at nearby Cortlandt Manor. Twenty thousand people showed up in support, with security provided by members of the longshore and electrical worker unions. Robeson, Guthrie, and others performed this time around without incident, but directly afterward violence erupted yet again.

As concertgoers and artists left via bus and caravan, another mob—again organized by the American Legion and KKK—pelted the passing vehicles with rocks. Some were dragged from their cars and beaten by rioters. Once again, local police stood by and did nothing; more than 140 people were injured. The aftermath saw Guthrie’s last big burst of songwriting. He had been in the same car as Seeger and Lee Hays on September 4, and had pinned his shirt against the window to prevent the shattering glass from injuring anyone. Says Kaufman:

In the weeks that followed, Guthrie was stung into action, reeling off a series of his angriest, most contemptuous, most defiant songs in a remarkable burst of energy—at least twenty-one songs about Peekskill written within a month. Collected in a makeshift volume titled “Peekskill Songs,” they were for the most part parodies of traditional and early country music standards.

Twenty-one songs is a lot—especially when considering that they were all written about the same series of events—but it also gives one an idea of just how much the events of Peekskill had affected him. It’s all the more impressive when one considers that Guthrie’s own father was likely in the Klan. Peekskill represented something of a last stand—both for Guthrie and for the radical workers’ subculture he had helped forge. By 1949, anticommunists like Joe McCarthy were already rounding up suspected subversives, pressing them to testify before Congress, and whipping up furor over “commies.”

This witch-hunt was most famously wrought in the world of culture and entertainment. Countless screenwriters, actors, directors, and musicians had their careers ruined. Paul Robeson, proud and defiant, was blacklisted and had his passport revoked for refusing to name names. His career never fully recovered. Even some of the Almanac Singers—including Burl Ives and Josh White—caved to the pressure and gave names to the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Seeger himself escaped by the skin of his teeth, and was one of the few to maintain any kind of music career outside the coffeehouses with his much-sanitized Weavers.

As for Guthrie himself, he would be restricted from speaking and singing his mind too, but for a different reason. He had been diagnosed with Huntington’s disease some years earlier, the same disease that killed his mother. Though he tried to keep his guitar in his hands and continue writing, his motor skills deteriorated, and he died on October 3, 1967, at the age of 55.

Bound for glory, bound for freedom

We’ll of course never know what Guthrie might have thought about the upsurges of the 1960s; by the time he passed away he had long lost his ability to speak. According to many accounts, his biggest fear during these final days was that his legacy would be forgotten. In the 1950s, before his strength had been completely sapped, he had taken his son Arlo into the backyard of their home several times to teach him “This Land Is Your Land” in its entirety, including the lost verses. Perhaps he needn’t have worried. As we now know, “This Land” became iconic during the 1960s. Despite the contradictory way in which it was often used, the song’s lost verses didn’t stay lost forever. The month of Woody’s death was also, by coincidence, when Arlo released his famed, eighteen-minute song “Alice’s Restaurant,” humorously skewering America’s military draft. The resemblance to his father’s own “talking blues” songs was, naturally, uncanny.

Arlo obviously wasn’t alone. Despite the best efforts of McCarthyite America, the generation of “folk-rock” artists that emerged in the 1960s had imbibed Guthrie’s progressive spirit along with his aesthetic. Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, the Byrds, Tom Paxton, Phil Ochs, Neil Young, Buffalo Springfield, and countless others cited him as an influence. All at one time or another wrote songs protesting the Vietnam War and supporting civil rights, and some, in a few select cases, openly called themselves revolutionaries.

Chances are that if you’re a musician with even the slightest social consciousness, then you’ve been influenced by Guthrie in some way. The radicalism he brought into his songs was seldom forced; it was organically and seamlessly connected with a kind of humanistic appreciation of working people’s everyday struggles.

Steve Earle describes Guthrie’s music this way: “I don’t think of Woody Guthrie as a political writer. He was a writer who lived in very political times.” Earle, one of Guthrie’s many inheritors, may be right. It’s hard, however, to find a moment in contemporary history that wasn’t political. Maybe that’s why the Guthrie that has reemerged so many times in popular music has been Guthrie the radical. This goes well beyond just the limits of the 1960s folk revival. In the early 1970s, a young man named John Graham Mellor—later known as Joe Strummer of punk icons the Clash—grew his hair long and insisted his friends call him Woody.

Guthrie’s lyrics have been set to music by the Celtic punkers Dropkick Murphys, and respun by Billy Bragg and Wilco in the sublime Mermaid Avenue sessions. Even Alabama 3, the London-based electronic group best known for composing the theme for The Sopranos, cite Guthrie as an influence.

No doubt, “This Land Is Your Land” has long since ceased to be the de facto anthem of the Obama administration. Even when it was, it was on a shallow basis. It’s appropriate, then, that both Springsteen and Seeger have shifted their enthusiasm to the Occupy movement. It was Seeger along with Arlo who performed “This Land” at Zuccotti Park during the height of Occupy Wall Street.

Springsteen, often recognized as Guthrie’s heir apparent, released his Wrecking Ball album in March 2012, a searing mix of folk-rock that frankly asks “Where’s the promise from sea to shining sea?” The Boss has also declared he will not be campaigning for Obama in 2012.

What does all of this say? Would a hundred-year-old Woody Guthrie be more over the moon for another Democratic president, or the first open-ended American class struggle in two generations? It’s an honest question; the Communist Party that he loyally followed his entire life went through some erratic shifts between ultraleft posturing and craven support for the Democrats and America’s policies abroad. Parsing out the kernel of genuine liberation is difficult with such an organism.

That kernel is most surely there, however; Guthrie made a point of highlighting it every chance he got. He was, in his own words, “out to sing songs that will prove to you that this is your world.” His songs, at their very best, have this woven into their fabric. It’s a cold, hard, undeniable fact.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Google+

Google+ Tumblr

Tumblr Digg

Digg Reddit

Reddit StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon