In defense of Political Marxism

Debating the transition

THE PAST few years have seen the publication of a series of contributions to the corpus of Marxist writings on the transition to capitalism. New books by Neil Davidson, Charlie Post, Jairus Banaji, and Henry Heller have garnered significant attention on the Marxist left. This recognition is indicative of a growing interest on the left in aspects of this thorny historical and theoretical issue. For those who are not yet well versed in the enormous literature produced by the long-running Marxist debates on the subject, navigating the different positions can be difficult—and understanding why the topic is an important one can be even harder.

But what’s at stake in these debates isn’t simply divergent accounts of how capitalism came into being; our understanding of how capitalism emerged is inextricably bound up with a range of contentious theoretical questions—for instance, different notions of base and superstructure and alternative understandings of the Marxist theory of history. Thus, different analyses of the transition lead us toward different approaches to other historical and social processes.

These debates are also closely related to conflicting notions of what properties define capitalism; disagreements about the transition often rest on disagreements about the nature of the system, the structural features that differentiate it from other modes of production, and its relationship to precapitalist (and potentially postcapitalist) social systems.

In that way, debates over the transition to capitalism are not necessarily detached from debates over political strategy. While the practical consequences of one’s position on the transition tend to be more indirect for us today, in previous epochs that relationship was more significant.2

One of the major focuses of much of this recent Marxist work on the rise of capitalism has been the ongoing disputes over the relevance of “Political Marxism” for efforts to understand transformative historical processes like the transition. It is a testament to the influence exerted by the theorists associated with this approach that so much effort has been devoted to assessing, elaborating upon, or challenging their arguments. In that regard, Ashley Smith has performed an important service by introducing readers of the ISR to “Political Marxism” in two reviews he has published in the past several months.3 But we worry that in his zeal to disabuse his audience of the notion that Political Marxism represents an insightful Marxist analytical framework—a particular point of emphasis for Smith in his very positive review of Henry Heller’s recent book—Smith ends up painting a misleading picture of Political Marxism.

Reading Smith’s latest review, the inescapable conclusion is that Political Marxism rests on a narrow and mechanical understanding of capitalism’s emergence, one that rejects key elements of the Marxist theory of history. We think that, on the contrary, the most significant contributions of Political Marxism have helped develop an approach that is deeply dialectical. Beginning with Marx’s analysis of the particular laws of motion of the capitalist mode of production, the so-called Political Marxists seek to reassert the historical specificity of capitalism and to situate it within its world-historical context. Their starting point is the unique set of relationships between a class of exploiters and a class of direct producers who perform the labor necessary to meet societies’ material needs. It is these exploitative class relations that determine the broad contours of all social and historical developments, and set the foundations on which all social life rests. To understand capitalism, it is therefore necessary to begin with the exploitative and conflictual social relationships that shape its basic character: that is, the relationship between wage labor and capital.

The emergence of capitalism’s particular “social-property relations” (to use Robert Brenner’s term) represented a sharp break from previous epochs of human history, because for the first time neither the exploiters nor the direct producers are able to rely on non-market means for their survival; it is the generalization of market dependence that gives capitalism its particular character—for instance, its unprecedented propensity for ongoing productivity growth. And it follows that the transition to capitalism could not be accomplished merely through an extension of age-old practices like commercial investment and trade, but only through the imposition of new social relationships (and thus new rules of “reproduction,” or survival) on exploiter and exploited alike.

What makes this social relations centered view of capitalist society and its origins so important is that it counters the tendency of bourgeois ideology—and, indeed, of many Marxist accounts of the transition—to read the unique logic of capitalism back into precapitalist societies, and thus to assume precisely what must be explained.

Capitalism in the eyes of bourgeois ideologues

To recognize the significance of the Political Marxist view of the transition, it’s useful to begin by laying out the alternative approach offered by its critics—that is, what Ellen Meiksins Wood, a prominent theorist of Political Marxism, has labeled “the commercialization model.”4

For the theorists of the bourgeoisie, capitalism is defined not by a particular set of exploitative social relationships, but by the growth of the market—a development that, at the end of the day, results from human beings’ natural propensity to engage in trade to satisfy their particular wants and needs. Underlying this view is the notion that human beings will, as Adam Smith put it, tend to “truck, barter, and exchange” in order to make money or access goods and services they desire, unless they are otherwise prevented from doing so.5 Bourgeois social theorists have identified a variety of factors that allegedly prevented the full flourishing of market rationality before the modern era (such as the low level of technological development, the dearth of money-capital available for investment, and the restricted character of existing market institutions).

But whatever the particularities of their accounts, they assume that once these impediments to the extension of market determination were removed, the functioning of the invisible hand would ensure that self-interest would lead potential buyers toward potential sellers, and vice versa. Subsequently, ever-wider swaths of society would adapt themselves to the dictates of the market in order to take advantage of expanded opportunities for trade. Precapitalist economic practices would gradually be superseded and the emergence of capitalism in its recognizably modern form would ensue.

One very important implication of this perspective is that wherever you find investment in profit-seeking, market-oriented ventures, you find the logic of capitalism. And since as far back as the beginnings of recorded human history there have been merchants and money-lenders engaged in the search for the greatest possible returns from investments in trade and finance, capitalism, at least in embryonic form, has been evident across the annals of time.

Marxists and the commercialization model

In much of the work that Marxists have done on the transition to capitalism, from Marx’s time to today, the influence of this bourgeois ideology is apparent: the rise of capitalism is, in these writings, usually analyzed in terms of the flourishing of age-old practices like trade.

In Marxist versions of the “commercialization model,” some combination of expanding trading networks, technological innovation, and an influx of large pools of money or wealth into feudal society precipitate embarkation down the path of capitalist development. The rise of a protocapitalist economy within the interstices of feudalism spawns a nascent capitalist bourgeoisie, which earns its living from trade and investment rather than feudal dues and the like. The subsequent growth of the market—as well as the concomitant expansion of both new types of manufacturing industries and of towns as centers of production and trade—weaken the bonds of feudalism. At a certain point, however, the further progress of the emergent capitalist economy is blocked by the continued dominance of the old feudal ruling class. The result is explosive conflicts between the forces of the ancien régime and a popular anti-feudal coalition spearheaded by the burgeoning capitalist class, eventually precipitating the defeat of the former.

There are many problems with this narrative but the basic one is this: the commercialization model assumes the pre-existence of a specifically capitalist logic, embodied in market-oriented economic practices, in order to explain how capitalism came into existence. It thus rests on a tautology. Whatever the particularities of different versions of the model, they all assume that the transition to capitalism resulted from the growth of a capitalist bourgeoisie on the basis of expanding opportunities for commercial exchange.

The legacy of the commercialization model is clear in the first major Marxist debate on the transition to capitalism, which took place between economists Maurice Dobb and Paul Sweezy in the 1950s. Sweezy had criticized Dobb’s book Studies in the Development of Capitalism for arguing that capitalism grew out of contradictions within feudalism, specifically the struggle between lords and peasants. Instead, Sweezy argued feudalism contained no contradictions powerful enough to generate an entirely new system of production, and that the dissolution of feudalism and growth of capitalism were accomplished by the external force of a growing world market. Sweezy’s reliance on the commercialization model is quite explicit: in his account capitalism arises from lords and peasants taking advantage of the new opportunities world trade presents them.

Dobb’s argument, however, contained similar weaknesses. He argued that feudalism’s stagnant technological growth led to increasing class conflict between lords and peasants, and that the peasants’ success in fighting off the lords’ attempts to claim more of the surplus through extra-economic coercion left the peasants able to begin reinvesting their profits in production, beginning a process of class differentiation that would end in fully capitalist social relations. Here, again, capitalism arises as a result of new opportunities for profit-making. While the source of the opportunity differs in Sweezy’s and Dobb’s accounts, both assume that, given the chance, people under feudalism will begin pursuing profit on the market in a way that is fundamentally the same as the practice of contemporary capitalists.6

The historical specificity of capitalism

The starting point for Political Marxists is “capital,” which—following Marx7—they conceptualize not as a pool of wealth or resources, a sum of money available for profit-seeking investment, or a collection of tools that can be used in the production process, but as a social relationship.

That’s a crucial distinction, because it is this latter notion of “capital” that is at the core of Marx’s unique and original analysis of capitalism: in the three volumes of Capital, Marx explains the laws of motion of capitalism as a system defined by the unceasing accumulation of capital. “Capital accumulation” in the Marxist lexicon isn’t simply a synonym for efforts to garner profits through trade or production for market-exchange. Nor does it refer merely to conditions of competitive accumulation: long before capitalism, different groups of exploiters were fighting amongst themselves over control of productive assets—with the losers in these conflicts facing dire consequences.

Instead, capital accumulation is a shorthand way of describing the particular structural drive by which capitalists are forced to engage in a never-ending battle to cut their costs and boost their market share in order to maximize their profit rates vis-à-vis their competitors—or else face the threat of bankruptcy. The emergence of those imperatives presupposes a shift toward characteristically capitalist forms of exploitation, resting on the generalization of market dependence. It is only when both exploiters and exploited have no alternative to reliance on the market for their survival that the logic of capitalism becomes possible.

To understand this point, it’s important to think about how exploitation is carried out under capitalism: in our society, workers are hired by businesses in return for a wage or a salary. Business’s willingness to provide employment depends on the profits earned from the fruits of workers’ labor—thus, if a capitalist enterprise finds that it could earn a higher return by firing some of its employees, it will do so, whatever the impact on the lives of the newly unemployed workers and their families. That’s not necessarily because the people who run capitalist firms are greedy or immoral: whatever their personal inclinations, capitalists must seek to maximize their profit rates, vis-à-vis the competition, or else run the risk of eventually being swallowed up.

Exploitation under capitalism thus occurs via market mechanisms: in selling their labor power, workers are simultaneously agreeing to forfeit a surplus product generated by their own toil (that is, on top of the labor they perform which creates the total value embodied in their wage); this is the source of capitalists’ profits. Workers’ willingness to accept this situation flows from the fact that they rely on these wages for their own survival: since capitalists have a monopoly on the means of production, and can decide whether or not their capital will be invested in employment-generating productive enterprises, workers have no other way of keeping themselves alive other than by selling their labor power; they can only provide themselves and their families with the material necessities of life by finding and keeping a job, even at the cost of endemic exploitation.

Meanwhile, capitalists are driven by the competitive pressures bearing down on them to try to maximize the amount of surplus value they extract from workers’ labor. But the way they go about doing this reflects the specific form of exploitation under capitalism: since workers can be hired and fired as needed, they can be replaced by machines that boost the productive capacity of the remaining workforce. This crucial fact allows employers to cut their wage bill without cutting their output, by substituting machines for a portion of their workforce. Thus, through the use of labor-saving technologies, capitalists can increase the total amount of surplus they take from their workforce without increasing the number of workers they employ.

And indeed, capitalists are compelled to utilize this as their primary strategy for securing a greater surplus from the labor performed by their workers: in order to avoid falling behind other more efficient producers, they are driven to continuously reinvest any profits they earn back into the productive process. The result is an ongoing drive to improve efficiency that is the hallmark of capitalist competition.

It is this propensity toward productivity growth through the introduction of labor-saving innovations into the productive process—in Marxist terminology, through increases in “relative,” as opposed to “absolute,” surplus value extraction—that differentiates capitalism from all precapitalist societies. Or to put it another way, capitalism is unique among class societies in the way that it tends to continuously revolutionize the productive forces.

All of this presupposes that the class of producers that performs the labor necessary to meet society’s material needs has been separated from non-market access to their own means of survival. Only when this is accomplished can the imperatives of market-based exploitation take hold. It was therefore the historical process by which the direct producers were left “doubly free”—that is, free from both feudal dues and obligations, and free of non-market access to the means of production—that Marx, in volume I of Capital, describes as the “real secret to the primitive accumulation of capital.”

Rules of reproduction of precapitalist societies

The onset of generalized market dependency transformed the nature of exploitation. What prevented precapitalist societies from developing the unique logic of capitalism was not the underdevelopment of the productive forces or restrictions on the expansion of commerce; instead, it was the fact that the core groups of direct producers retained non-market access to their own means of subsistence. As a result, the various exploiter classes that existed before the rise of capitalism could not use their control over access to the means of production, and thus reproduction, to wrest a surplus product from the labor of the subordinate classes. Peasants in feudal Europe, for instance, had customary access to their own plots of land, which they could use to grow food and other items required for their own survival. Lords could, therefore, not use the threat of dismissal to discipline them.

They thus had to rely on alternate means for securing control over the surplus product: at base, these rested on what Political Marxists have called “extra-economic coercion.” The key point is that precapitalist ruling classes depended on the capacity to mobilize sufficient violence, or the threat of it, to induce the direct producers to hand over the surplus product created through their labor. The feudal dues and obligations that peasants transferred to lords could take many different forms at different times and places. And the level of these dues was set by tradition, and sometimes codified into law. But it was only the lords’ capacity to mobilize what was essentially military force that prevented the peasants from keeping more (or all) of what they produced for themselves, or from trying to flee to find a better deal elsewhere. Similarly, slavery is impossible unless the slave owner(s) have enough coercive power to cohere and maintain a large force of unwilling slave laborers.

The dependence of precapitalist ruling classes on direct coercive power exerted a decisive influence over the strategies they used to improve their competitive position. In the context of precapitalist modes of production, property was always “politically-constituted.” For example, every lord had to set himself up as a mini-state, with his own armed force. As a consequence, there was a constant push by precapitalist ruling classes to accrue ever greater resources in order to purchase still greater means of coercion for use against other lords and exploited peasants alike. But the manner in which they procured more effective means of coercion was indicative of the precapitalist propensity for increasing “absolute” surplus value, by working peasants harder or expanding the scope of production (through incorporation of previously unsettled lands or the conquest of new territories).

Peasants, meanwhile, engaged in an ongoing struggle with lords over the terms and conditions of their own exploitation: their aim was to reduce the level of dues they were required to provide and to guarantee their own control over the land. But the logic of their position led them to focus on production for subsistence; they tended to produce as much of the necessities of their survival as possible, while marketing only a small surplus. Specialized production for market exchange, however, made little sense in circumstances where peasants controlled their own means of subsistence. In the absence of market dependency, peasants had no reason to subject themselves to the ups and downs of the market. Rather than producing one or two cash crops and relying on the purchase of the food, clothing, etc., for their own reproduction, peasants instead sought to grow a wide array of crops so as to meet their variegated needs.

In that context, the possible emergence of a market for mass consumer goods as well as the formation of a potential supply of wage laborers available for any precocious would-be capitalists who might hire them was blocked by the very structure of precapitalist societies.

The Political Marxist view of the transition to capitalism

In this way, the “rules of reproduction” associated with precapitalist societies lacked any equivalent mechanisms capable of producing the sort of self-sustaining productivity growth that is the hallmark of capitalism. This qualitative difference between the laws of motion of capitalist and precapitalist societies is why the latter could not simply evolve into the former through an expansion of trade or an influx of wealth. Thus, while the Italian city-states of the Renaissance era gained enormous wealth and power by turning themselves into centers of trade and finance, they failed to experience the takeoff towards self-sustained growth emblematic of capitalism. Instead, the ruling-classes of Renaissance Italy utilized their wealth in various speculative financial endeavors or to buy themselves superior means of military power. But they didn’t reinvest it back into the production process. Similarly, while the colonization of the Americas and other non-European regions of the globe led to an influx of money and resources into Europe during the Early Modern Period, the countries that initially drove this process, notably Portugal and Spain, tended to invest their newfound riches on improved means of warfare. The two societies also failed to make the leap to systematic growth through increasing relative surplus value extraction.

This is an especially important consideration, because these cases have often been described as examples of “protocapitalism” by Marxist theorists of the transition. The implication is that what prevented further development along capitalist lines was the relative weakness of the nascent capitalist bourgeoisie in the face of entrenched precapitalist ruling classes.

But this assumes precisely what is contested by the Political Marxists: that the logic of capitalism already existed and only required the removal of various impediments to its diffusion in order to flourish. If, instead, the Political Marxists are correct to argue that the “merchant capital” and “finance capital” that were so pervasive in precapitalist societies did not really constitute “capital” in the Marxist sense at all, then the failure of these societies to make the leap to capitalism becomes more explicable: as opposed to examples of failed transitions from “protocapitalism” to capitalism, the rise and subsequent decline of these once powerful leaders in the areas of trade and transoceanic exploration reflects the structural dynamics of their underlying models of accumulation. Rather than instances of burgeoning capitalist economies that saw their development blocked by impediments to the rise of market exchange, they are part of a long line of precapitalist societies that fostered the growth of market exchange without actually moving in the direction of capitalism.

Brenner’s account of the transition

For the Political Marxists, the transition to capitalism was a historical process that centered not on the expansion of market exchange, but on the imposition of new social relationships that rendered both exploiters and exploited subject to the imperatives of market dependence. Basing their historical accounts of the transition on the pioneering work of the historian Robert Brenner, they have traditionally claimed that the transformation of social relationships that precipitated the transition was a byproduct of agrarian class struggles in the English countryside in the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.8 The context for this shift was a general crisis of European feudalism, the onset of which was signaled by the Black Death that swept across the continent in the middle of the 1300s: the subsequent period was marked by a sustained decline in population, endemic warfare, and heightened class conflict.

But if the crisis was continentwide in its scope, in most places it did not lay the groundwork for the rise of capitalism. In Eastern Europe, for example, the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries witnessed the imposition of what’s known as the “Second Serfdom.” Meanwhile in France, the peasantry was able to secure de facto ownership of their holdings and a long-term reduction in the real value of their dues, while the lords were forced to scramble for positions as tax collectors and officials in the increasingly centralized absolutist state—a state which grew strength at the expense of the aristocracy’s independent power, entrenching itself as the dominant force in French society, and extracting enormous resources for itself through an extensive system of taxation.

In neither case did the resolution of the general crisis of European feudalism lead to the sort of takeoff in productivity growth that is the hallmark of capitalism. In the English countryside, however, productivity growth began to rise sharply from the sixteenth century onward—an indication, for Brenner, that England had embarked on the road to capitalist development. That divergence cannot be attributed, he argued, to the effects of long-distance trade: indeed, in Eastern Europe, the onset of the Second Serfdom was tied to a move toward production of grain for export across the Baltic. Nor did it result from a weakening of the feudal aristocracy, which was, if anything, stronger in England than in France by the end of the fifteenth century.

What differentiated England, instead, was the particular configuration of class forces that arose there in the centuries before the 1500s. The structure of English society meant that neither lords nor peasants were strong enough to impose their will on one another out of the feudal crisis of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries: while the lords were unable to restore serfdom, the peasants were too weak to establish de facto ownership over the land. Nor was the English monarchy powerful enough to erode the independence of the lords; although autonomous from the control of any particular aristocratic factions, the English state was always subject to the influence of the lords as a group. Thus, rather than a threat to the foundations of lordly power, the monarchy emerged as the arbiter of the lords’ collective interests.

In these circumstances, the competition between English lords for resources, intensified as it was during an era when English society was recovering from its demographic collapse, could no longer be conducted in the old way: competing over the limited resources drawn from a peasantry still far too scarce to provide a surplus sufficient for their total needs, the lords were too strong to be dispossessed of their power, but too weak to provide themselves with a sufficient surplus by means of exploitation via extra-economic coercion. In that context, the lords began to offer leases to tenant-farmers, on the basis of annual or biannual contracts. Since these tenant-farmers could retain anything they produced above the value of the rent they paid to the landlords, but could also be ejected from the land once their lease was up if the landlord found another tenant able and willing to pay more, they were compelled to improve the land in order to increase their output. In this way, a market in leases began to take shape, with the losers rendered landless—and, thus denied access to the means of production, turned into a potential pool of wage labor available for hire.

The generalization of market dependency as the core change

For Brenner, the key outcome of this process was the generalization of market dependency: no longer unable to reproduce themselves through non-market means, both exploiters and exploited were subject to the imperatives of the market.

That shift didn’t immediately lead to the emergence of the capital/wage labor relationship that would eventually come to define the class structure of capitalism. In part, that’s because the resistance to wage labor was so great that dispossessed peasants tended to prefer vagabondage to the discipline of capitalist production. As a consequence, the state was forced to intervene with legal measures that made failure to find work a criminal offense—punished, for instance, by imprisonment in the brutal poor-houses that became common features of capitalist society during its early days.9

Still, it was the generalization of market-dependence—and not, it should be noted, the widespread use of wage labor10—that differentiated capitalist societies from their precapitalist counterparts, because it was that shift that set the stage for the takeoff toward self-sustained growth of the sort that would soon make England the wealthiest and most powerful society the world had ever known. More generally, theorists associated with Political Marxism have insisted that as long as the direct producers retain access to their own means of production and exploitation is carried out by means of extra-economic coercion, there can be no capitalism.

The bourgeois revolutions

The view of the transition associated with Political Marxism thus rejects the notion that the growth of the market was the key factor precipitating the transition to capitalism. Implicit in such claims is the assumption that the logic of capitalism already existed, and needed only the elimination of one or another barriers to its progress in order to emerge more fully.

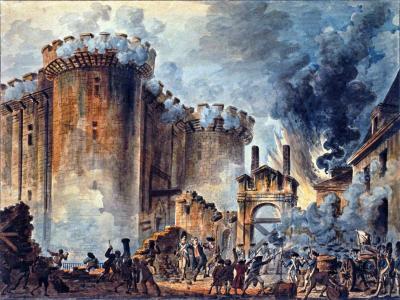

Understanding this can help shed light on the contentious arguments made by the Political Marxists regarding the traditional theories of the “bourgeois revolution.” Classically, this concept referred to mass popular revolts against the existing order that succeeded in toppling the ancien régime and thereby facilitated the development of capitalism, notably, the Dutch Revolution of the sisxteenth century, the English Revolution of 1640, and the Great French Revolution of 1789. For well over a century, Marxist theorists have analyzed these events as turning points in the transition to capitalism: they were conceptualized as necessary challenges to the vestiges of the precapitalist state and class structures, led by an increasingly powerful and self-confident capitalist bourgeoisie heading a popular coalition and now given new impetus by a crisis of the old order as well as the spread of radical new ways of thinking (for instance, the French Enlightenment); their culmination was held to be the elevation of this bourgeoisie to the position of ruling class, as the last blockages to capitalism’s growth were cleared away.11

In the past, the Political Marxists have questioned key elements in this narrative: most importantly, they have insisted that the entire notion of a bourgeois revolution tends to assume capitalism’s growth in order to explain its liberation from the shackles of feudalism.12 In France, for example, they conclude, the Revolution of 1789 was neither preceded by the onset of capitalist development, nor gave way to a renewed burst of capital accumulation. More pointedly, they note that to the extent these were popular revolutions, they involved mass mobilizations and intense social struggles around popular demands that were antithetical to the interests of capital accumulation. Thus the aims of the Parisian sans-culottes reflected their concern to buffer themselves from market imperatives; the radicalization they spearheaded during the early, ascendant phase of the revolution, served to impede the growth of the market.13

Recently, a variety of Marxist theorists have suggested that this traditional understanding of the bourgeois revolutions requires tweaking: accepting criticisms that the classical conception of the bourgeois revolution overgeneralizes from the French experience, and struggles to account for the seeming failure of the bourgeoisie to consistently play its allotted historical role, they have sought to replace the traditional view with an outcome-based approach. In this revised conception, any historical process that leads either to the creation of a new center of capital accumulation or to the reorientation of the state to the requirements of capital can be accounted as a bourgeois revolution.14

Given the difficulties with the classical understanding of “bourgeois revolutions,” many Political Marxists have questioned whether the category itself doesn’t obscure more than it clarifies. Others, however, have adopted this revised definition of bourgeois revolutions. Indeed, this updated version of the concept is entirely compatible with the basic analytical assumptions guiding Political Marxism—indeed, Political Marxists agree both that the shift toward capitalist social relations alters the terrain on which political conflicts are fought out, and creates enormous new pressures on state elites pushing them to prioritize the needs of capital accumulation or face the prospect of being removed from power.15 Additionally, Ellen Meiksins Wood has given an account of capitalist states internationally that emphasizes the persistence of imperial competition in a way quite congruent with analyses of imperialism put forward in this journal.16

The key criteria for this outcome-based approach is, therefore, whether the historical process in question really did facilitate the development of capitalism. That of course is an empirical rather than a theoretical question.

Forces of production and historical change

Today, the main alternative to the Political Marxist view of the origin of capitalism is that developed primarily by Chris Harman, and recently defended by Henry Heller. This account purports to chart a path between the commercialization model and Brenner’s arguments, basing itself on the theory of history Marx sketches in his 1859 Preface to the Contribution to a Critique of Political Economy. In this text, Marx argues,

At a certain stage of development, the material productive forces of society come into conflict with the existing relations of production or—this merely expresses the same thing in legal terms—with the property relations within the framework of which they have operated hitherto. From forms of development of the productive forces these relations turn into their fetters. Then begins an era of social revolution. The changes in the economic foundation lead sooner or later to the transformation of the whole immense superstructure.17

In this account, the growth of the productive forces—the ability of people to transform their natural environment to fit their needs—forms the motive force of history. After a certain amount of growth, these forces come into conflict with the relations of production, and a crisis ensues in which the relations of production are transformed.

Harman and his cothinkers have attempted to elaborate on Marx’s brief sketch by developing an account of the transition to capitalism that emphasizes the growth of the productive forces under feudalism, and the way this growth created new opportunities for profit-making that gradually undermined the old feudal order. Merchants, for example, could take advantage of new productive techniques to begin employing wage labor.18 This, in turn, brought them into conflict with the feudal state, which attempted to repress these new capitalists to prevent them from becoming a threat to its power. For Harman, this conflict between the feudal state and the nascent capitalist class is key to explaining why capitalism emerged in Western Europe before China or India, which often had more advanced productive techniques than Europe—in those societies, the centralized state was able to hold on to control, while in Europe the decentralized feudal system allowed capitalism to grow in the cracks.

As should be clear, Harman’s account represents more of a modification of the commercialization account than an actual alternative to it. Capitalism is still presented as a form of production that develops when opportunities for profit making arise, and its historical specificity is elided. In the work of early capitalist ideologues like Adam Smith, these opportunities present themselves when the “irrational” constraints of the feudal state, like mercantilist trade policies, are removed. Essentially, Harman modifies the commercialization model by adding two more preconditions for capitalist production: free labor and a certain level of development of the productive forces.

Harman rightly notes that, for Marx, “the separation of the immediate producers (those who did the work) from the means of production” formed a precondition for the emergence of capitalism.19 However, he undermines this point by arguing that the development of the productive forces itself tends to accomplish this separation more or less automatically, by simultaneously increasing the cost of the means of production as production becomes more technologically sophisticated (making it harder for the producing class to acquire the means of production), and creating a new demand for wage laborers, since these new productive techniques required more skilled and motivated workers.20

Neither of these mechanisms is sufficient to accomplish the task Harman has set out for them. For one thing, while more technologically sophisticated methods of production can be more expensive, it is also true that, as methods of production become more efficient, the means of production can actually decrease in cost, as they become easier to produce. The mere fact of increasing efficiency of productive techniques does not assure that the means of production will grow so expensive that the producing class cannot acquire them21; indeed, it is just as plausible that increases in efficiency will make them more affordable. Harman’s second mechanism doesn’t even get this far. In arguing that new productive techniques make it more profitable to employ wage labor, he presupposes that wage labor is there to be employed. Here, Harman simply assumes that which he attempts to explain.

Harman’s attempt to replace the commercialization model thus yields instead an untenable technological determinism, in which the relations of production yield passively to changing technologies.22 The historical specificity of the imperatives of capitalist accumulation is occluded, and capitalist relations of production are held to follow quite naturally from a certain level of development of the productive forces.23 As long as a state strong enough to block the advance of a capitalist class is absent, capitalism will result from people taking advantage of the opportunities for profit that present themselves.

Political implications

The case for Political Marxism isn’t limited to its better conceptualization of the origins of capitalism. It also has important political consequences. Perhaps the most central of these concerns our ability to theorize the capitalist state. Unlike previous modes of production, capitalism does not rely on the direct coercion of the producing class. Whereas feudal lords rely upon their soldiers to force peasants to give up their harvests or work on their plots, capitalists rely, in Marx’s famous phrase, on “the dull compulsion of economic relations.” The fact that the ruling class under capitalism is uniquely able to appropriate the social surplus without the direct use of coercion has a host of implications for thinking about the capitalist state. On the most basic level, it entails what Wood has called “the separation of the political and the economic under capitalism.” In previous modes of production, political and economic power were concentrated in the same hands. To maintain his position as exploiter of his peasants, a feudal lord required substantial means of coercion—soldiers, weapons, etc. Under capitalism, however, political and economic power are separated. The capitalist class does not command the coercive apparatus—the military and the police—in our society, and the political class does not control production.24

This separation allows for a degree of political democracy under capitalism, if workers are able to win it. While precapitalist modes of production require that the producing class, whether serfs in Russia or slaves in ancient Greece, be rigorously excluded from political power, capitalism is perfectly compatible with workers being able to have a say in government. In the United States, with its shambolic two-party system, it may be tempting to conclude that this hasn’t meant much. But in countries with more powerful workers movements, the importance of this fact becomes clear. In Western Europe, for example, mass parties of the working class were able to govern for substantial periods of time in the post–World War II era, constructing massive welfare states that enhanced the power of the working class in the manner described above. These parties’ subsequent turn toward neoliberal austerity does not diminish the importance of this accomplishment.

The separation between the political and the economic under capitalism does not mean that the two are independent. Indeed, their formal separation conceals a deeper, dialectical unity. This separation, after all, is itself a product of the peculiarity of capitalist relations of production. On another level, the fact that the capitalist state is not generally a direct exploiter means that it is dependent upon the capitalist class to direct economic activity. Since states raise money through taxes on things like income, profits, and sales, when those things go down, as in a recession, the state loses money, and thus its ability to pursue projects of various sorts, be they imperial conquest or infrastructure improvement. In this way, the capitalist state, regardless of whether right-wingers or social democrats are running it, is dependent upon capitalists being willing to invest and continue production if it is to be able to pursue its projects. Moreover, when capitalists cease investing, and recession results, political instability is a frequent byproduct. Under capitalism, then, state managers, no matter what their political persuasion, must do their best to ensure that capital feels comfortable.25 Thus, the formal separation of the political and the economic under capitalism dialectically explains why the state under capitalism will always, in the last instance, act in the interests of capital.

Conclusion

Though we believe Political Marxism offers a superior perspective on both the origins of capitalist development and the nature of capitalism today, we do not think the political stakes in this debate are so high that they preclude collective organizing by people with differing views on the question. Advocates of Political Marxism such as Robert Brenner, Ellen Meiksins Wood, and Charles Post share a tremendous amount with their critics like Jairus Banaji, Neil Davidson, and Ashley Smith in their common perspective on the necessity for revolutionary socialism from below.

In the context of this shared perspective, debates about the transition can play a healthy role in clarifying the key concepts of Marxism. It is in the context of thinking and arguing about what defines capitalism that concepts like mode of production, relations of production, etc., come to be more developed. For that reason, debates about how capitalism came to be are no idle academic exercise, but part of learning how to think with Marxism as a theoretical guide—itself an indispensable aspect of the revolutionary project. The recent debates about the transition are thus a hopeful sign of a renewal of Marxist theory, and a contribution to the project of understanding capitalism in order to overthrow it.

- Jairus Banaji, Theory as History: Essays on Modes of Production and Exploitation (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2011); Neil Davidson, How Revolutionary Were the Bourgeois Revolutions? (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2012); Henry Heller, The Birth of Capitalism: A Twenty-First Century Perspective (London: Pluto Press, 2011); Charlie Post, The American Road to Capitalism: Studies in Class-Structure, Economic Development and Political Conflict, 1620–1877 (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2012).

- John Eric Marot’s recent book on post-revolutionary Russia, for example, argues that misconceptions over the extent of capitalist development in Russia led Trotsky to drastically overestimate the danger of capitalist restoration, and that this led to dire strategic errors in his battle with the Stalinist bureaucracy. John Eric Marot, The October Revolution in Prospect and Retrospect: Interventions in Russian and Soviet History (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2013).

- Ashley Smith, “A challenge to political Marxism,” ISR 86, November–December 2012; Ashley Smith, “Political Marxism and the rise of American capitalism,” ISR 78, July–August 2011.

- See Ellen Meiksins Wood, The Origin of Capitalism: A Longer View (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2002) and “The Non-History of Capitalism,” Historical Materialism, Volume 1, No. 1, 1997; 5–21.

- Robert Brenner discusses Smith’s views and legacy in Brenner, “Property and Progress: Where Adam Smith Went Wrong,” in Chris Wickham, ed., Marxist History-writing for the Twenty-First Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

- The key articles from this debate are collected in Rodney Hilton, ed., The Transition from Feudalism to Capitalism (London: Verso, 1978).

- As Marx argues, “In themselves money and commodities are no more capital than are the means of production and of subsistence. They want transforming into capital. But this transformation itself can only take place under certain circumstances that center in this, viz., that two very different kinds of commodity-possessors must come face to face and into contact; on the one hand, the owners of money, means of production, means of subsistence, who are eager to increase the sum of values they possess, by buying other people’s labor-power; on the other hand, free laborers, the sellers of their own labor-power, and therefore the sellers of labor. . . The process, therefore, that clears the way for the capitalist system, can be none other than the process which takes away from the laborer the possession of his means of production; a process that transforms, on the one hand, the social means of subsistence and of production into capital, on the other, the immediate producers into wage laborers. The so-called primitive accumulation, therefore, is nothing else than the historical process of divorcing the producer from the means of production. It appears as primitive, because it forms the pre-historic stage of capital and of the mode of production corresponding with it. Karl Marx, Capital, Vol I (New York: International Publishers, 1977), 714.

- For Brenner’s argument and some responses, see T.H. Aston and C.H.E. Philpin, eds., The Brenner Debate: Agrarian Class Structure and Economic Development in Pre-Industrial Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976). See also, Brenner, “The Origins of Capitalist Development: A Critique of Neo-Smithian Marxism,” New Left Review 104 (July/August 1977), 25–92.

- See Peter Linebaugh, The London Hanged: Crime and Civil Society in the Eighteenth Century (London: Verso, 1992).

- Wage labor in itself does not signify capitalism because wage labor alone is not the same as market dependency. Throughout the history of class society, there have been people who have found it more advantageous to work for wages rather than on the land. However, what differentiates wage labor under capitalism is that most people have no choice but to sell their labor power. In precapitalist societies, it was possible to acquire non-market access to the means of subsistence—in short, land—through various avenues. The rise of capitalism meant the end of this possibility, and consequently changed the character of wage labor.

- For useful examples of their approaches, see Christopher Hill, The Century of Revolution: 1603-1714 (New York: W.W. Norton, 1961); see also Albert Soboul, A Short History of the French Revolution, 1789-1799 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1965).

- For a summary of shifts in French Revolutionary historiography, see Peter Davies, The Debate on the French Revolution (Manchester: University of Manchester Press, 2006).

- George Comninel, Rethinking the French Revolution (London: Verso, 1987).

- The key text here is Neil Davidson, How Revolutionary Were the Bourgeois Revolutions (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2012).

- Here, it’s useful to compare Davidson’s “consequentialist” version of bourgeois revolution with Robert Brenner’s arguments in his study of the English Revolution, Merchants and Revolution: Commercial Change, Political Conflict, and London’s Overseas Traders, 1550-1653 (London: Verso, 1993).

- As Wood puts it: “At any rate, the development of a rudimentary global society is, and is likely to remain, far behind the contrary effect of capitalist integration: the formation of many unevenly developed economies with varied and self-enclosed social systems, presided over by many nation states. The national economies of advanced capitalist societies will continue to compete with one another, while ‘global’ capital (always based in one or another national entity) will continue to profit from uneven development, the differentiation of social conditions among national economies, and the preservation of exploitable low-cost labour regimes, which have created the widening gap between rich and poor so characteristic of ‘globalization.’ So the capitalist economy has an irreducible need for ‘extraeconomic’ supports whose spatial range can never match its economic reach.” Ellen Meiksins Wood, The Origin of Capitalism: A Longer View (New York: Monthly Review Press, 2002), 180. Passages likes this make it clear how misguided Davidson’s characterization of Political Marxism as a ‘Hayekian marxism,’ which ignores the state’s role, really is. At the same time, other writers associated with Political Marxism have argued that capitalism has no special inclination toward the territorially rooted nation-state, and would be perfectly fine with one global superstate. See Benno Teschke, The Myth of 1648: Class, Geopolitics, and the Making of Modern International Relations, (London: Verso, 2003).

- Karl Marx, A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1977).

- Harman’s arguments are actually quite different in different texts. In A People’s History of the World, the emphasis is very much on the expansion of commercial activity. He points to advances in the forces of production as being a necessary condition for this commercial expansion, but the actual work of explaining the tradition rests largely on commercialization (see especially A People’s History of the World (London: Bookmarks, 1999), 155–57 and 180–81). The arguments below engage with a later article, “The Rise of Capitalism,” which moves away from identifying the transition to capitalism with the expansion of trade, but still recapitulates some key aspects of the commercialization model—most importantly, the assumption that capitalist accumulation takes place through the removal of external barriers, such as restrictive states, and not through the transformation of the relations of production.

- Though Harman is correct to point to Marx’s identification of free labor with capitalism, he tends to misunderstand the reasons for free labor’s importance. Harman tends to argue that free labor mattered because workers had to be motivated to use the more advanced productive techniques of early capitalism, and serfs or slaves had no incentive to produce more efficiently. This view overstates the incentives for wage workers to engage in more productive labor—after all, advances in productive efficiency under capitalism frequently lead to workers being laid off! It also misses the key fact of wage labor—the fact that capitalists can expel workers from production whenever they please simply by firing them, making the introduction of labor-saving technology far more practical.

- Chris Harman, “The Rise of Capitalism,” International Socialism 102, 2004.

- Indeed, Harman’s argument slides quite rapidly toward a technological determinism of the sort employed by bourgeois apologists for the factory regime: the technological requirements of the new technology required the reorganization of labor in the factory. Stephen Marglin dissects this argument in his classic article “What do Bosses Do? The Origins and Functions of Hierarchy in Capitalist Production,” Radical Political Economy: Explorations in Alternative Economic Analysis (1996): 60–112.

- Harman makes it quite clear in this article that capitalism’s development is impeded by the existence of precapitalist states. He argues that China and Europe had basically identical modes of production and levels of development in the early modern era, but that China’s large state blocked the development of capitalism. This state-centric view of historical change offers no explanatory room for Marx’s key concept of the relations of production, which merely follow in the path of the productive forces.

- To argue that Harman’s view of the development of the productive forces forming a precondition to capitalist accumulation is wrong is not to deny that capitalism requires a certain level of productivity, as has sometimes been alleged. Rather, it is to argue that Harman mischaracterizes the nature of this precondition. The growth of the productivity of labor is necessary for capitalism because of the unplanned nature of capitalist production. The anarchy of the market, in which firms regularly fail and go out of business, requires that a social surplus well above the subsistence needs of the population be produced. If the social surplus were too small, it would quickly spell disaster for a society with capitalist relations of production, as the failure of a given firm could mean the end of the production of an essential means of subsistence.

- Objections here about groups like the Pinkertons, or Blackwater, or private prisons, are beside the point. Despite the existence of these groups, and indeed their importance in American history, for the vast majority of workers and employers, the discipline of the market has proved sufficient to ensure that capitalist accumulation continues.

- In the anodyne language of the bourgeois press, this is referred to as “business confidence.”

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter Google+

Google+ Tumblr

Tumblr Digg

Digg Reddit

Reddit StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon